Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

“An increasing number (of horses) are killed for rations and today 28 were especially shot for the chevril factory”. HA Nevinson war reporter for The Daily Chronicle.

Chevril Label (Talana Museum)

So often with history it is the main events that are carried down through time. The logistics to keep armies moving tend to be overlooked and the animals that suffered in wars also tend to take a back seat.

Horses played a vital role during the Anglo-Boer War. 360,000 horses out of a total of 519,000, were imported to South Africa including 50 000 from the United States and 35 000 from Australia – most of them landing in Port Elizabeth. 106,000 mules and donkeys out of a total of 151,000 were also brought into the country for the war.

Horse in transit (Talana Museum)

A variety of breeds of horses were used during the war. Many Boers used Basuto Ponies, that were well adapted to the rocky, mountainous terrain and were known for their endurance. The Boer horses were exceptionally hardy and nimble and could survive in all types of terrain and weather conditions.

War horses were workhorses, used as mounted infantry horses, gun horses, and cavalry horses. Not only were they ridden by soldiers, they were used to pull gun-carriages – at times through muddy battle grounds or over rough, uneven terrain as well as having to ford rivers and streams. Horses, mules and oxen were also used to pull heavily laden transport wagons.

A horse’s life expectancy, from the time of its arrival in South Africa was around six weeks. Sixty percent of the horses died in combat or as a result of mistreatment. Besides being killed in battle horses died as a result of

- The failure to adequately rest and acclimatise horses after the long sea voyages.

- The rough terrain of South Africa, which the imported horses were unused to.

- Exhaustion and dehydration, as a result of being ridden over hundreds of kilometres, in all kinds of weather, with little or no rest.

- Many horses sustained injuries to their fetlocks and hooves – there was not always the time or opportunity to treat the animals with the care they had been used to.

- The horses – unlike those used by the Boers – were unused to surviving on the veld grass, which for many was their food for much of the time. The larger size of the British horses made them more dependent on fodder that had to be imported.

- Overloading the horses with unnecessary equipment and saddlery.

- African Horse Sickness.

- Horses slaughtered for their meat, particularly during the sieges of both Ladysmith and Kimberley.

- Over 300 000 horses died during active service – not counting those on the Boer side. To provide some sort of understanding of the numbers, the war lasted for 970 days, which amounts to about 309 British horses dying a day.

The Boer horses also died in their thousands, many ridden to exhaustion. In most cases dead horses were not buried, but tended to be left where they fell.

“An army marches on its stomach.". This quote, attributed to both Napoleon and Frederick the Great, attests to the importance of forces being well-provisioned.

Prior to the outbreak of the war, an enormous stockpile of supplies had been sent to Ladysmith. In spite of these supplies, the inhabitants were to experience a severe shortage of food, reducing their rations to less than 25% of the normal issue and resulting in near starvation before the relief came. The Boers had cut the fresh water supply early in the siege and the only water available was from the Klipriver, which was contaminated and thus the cause of the high incidence of deaths from enteric and other diseases. Over 50% of the deaths during the siege were disease related, and not caused by the enemy.

Enteric or typhoid, as we know it today, is caused by contaminated food and water or close contact with infected persons. Symptoms include high fever, headache, stomach pain and constipation or diarrhea. In crowded conditions during the siege there was no means of preventing this from spreading. With proper rest, light food, clean water, and patience, a patient will recover – all things in very short supply in Ladysmith.

The Ladysmith garrison of 13,500 troops, under the command of Sir George White, who defended Ladysmith during its encirclement by the Boers, included 5,400 civilians plus a further 2,400 black Africans and Indians all living within the 12½ miles of the British defensive perimeter.

At the start of the siege, supplies were considered to be sufficient for two months and one month’s food supplies for the 9 800 horses, 2 500 oxen and a few hundred sheep. As the siege lengthened, the sick list continued to grow and rations started to run out. By the end of January 1900 there were 1,900 sick and wounded in the hospital, of whom 848 were typhoid cases and 472 were dysentery. The death rate rose to eight per day.

The following excerpts from the diary of Henry Wood Nevinson (HWN) and the long letter written to his wife by Herbert Watkins-Pitchford (HWP) give harrowing details of the extreme hunger of the inhabitants and the horses. HWP’s letter began on 27th October 1899 and finished on 1st March 1900 providing a frank account of life during the siege. Other comments from the diaries of civilians during the siege and letters from soldiers that were published years after the war show a very different aspects of the siege and how the horses suffered and became a food source that saved many a person in Ladysmith.

My great grandfather David Jones got caught up in Ladysmith, after getting away from Dundee. His death at a young age (34 years old) in January 1904 was attributed to the conditions and lack of food during the siege.

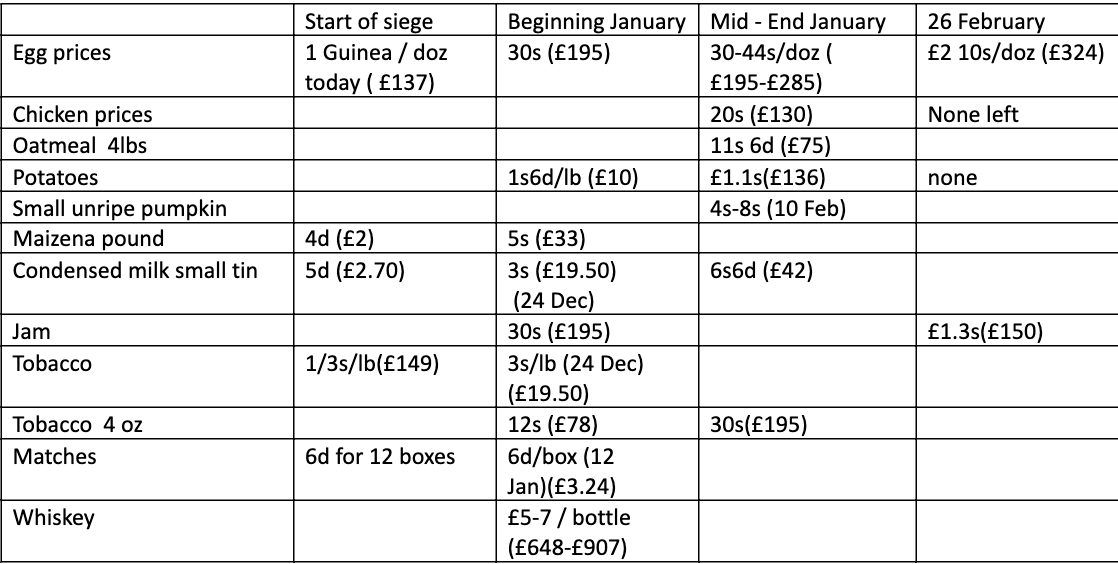

From the Ladysmith diary of Army Schoolmaster WH Gilbert, 19 and 22 December 1899: “Our provisions are getting very scarce… coffee, tobacco, jam, pickles and other necessaries. I don’t think I will ever again grumble at dry bread for tea, or complain if there is no milk in the jug.”

16 January 1900 (HWN)

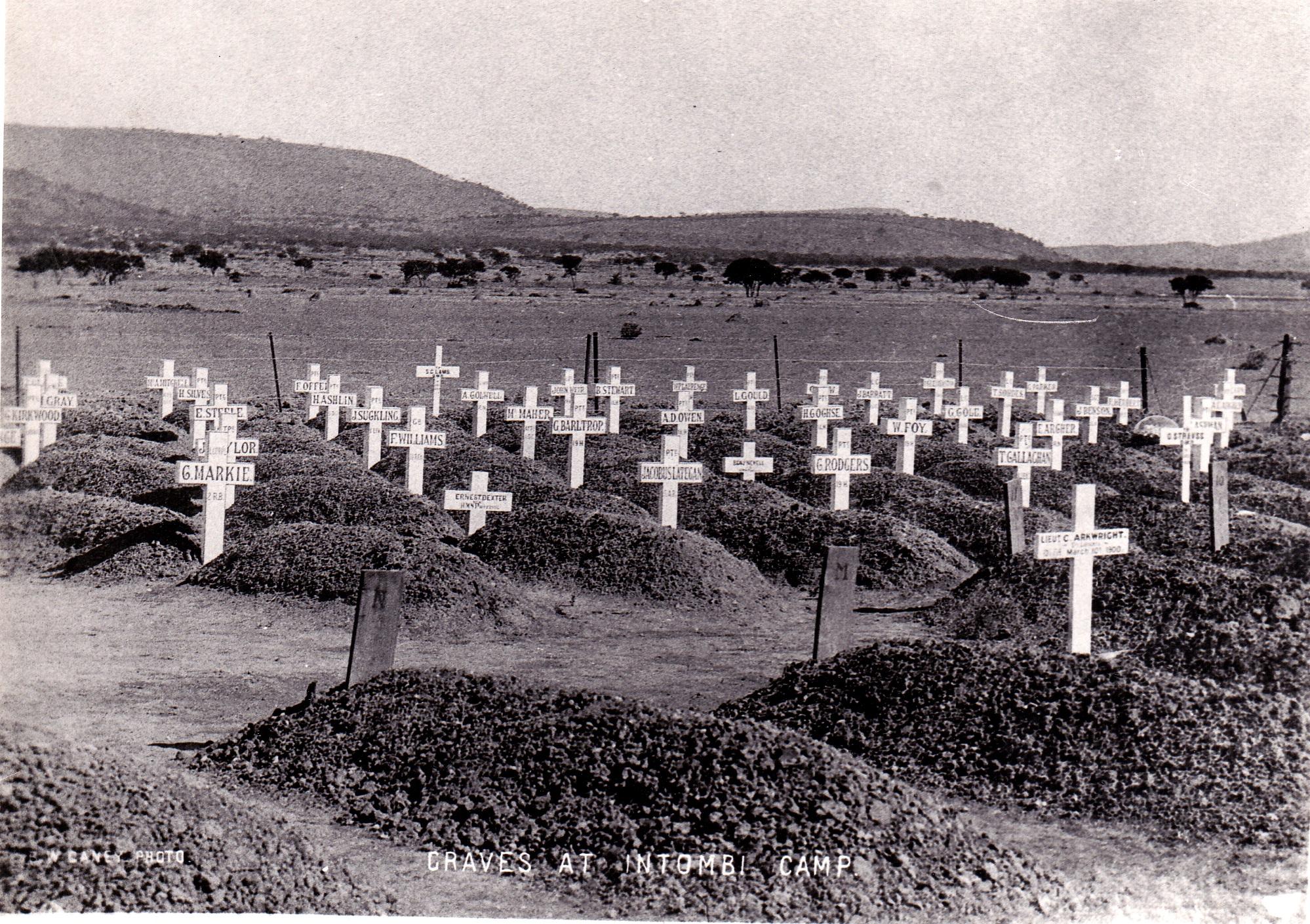

At the market, eggs were a guinea a dozen. Four pounds of oatmeal sold for 11s.6d. A four–ounce tin of English tobacco fetched 30s. Out of our original 12 000 nearly 3 000 are now sick or wounded at Intombi and there are over 200 graves there.

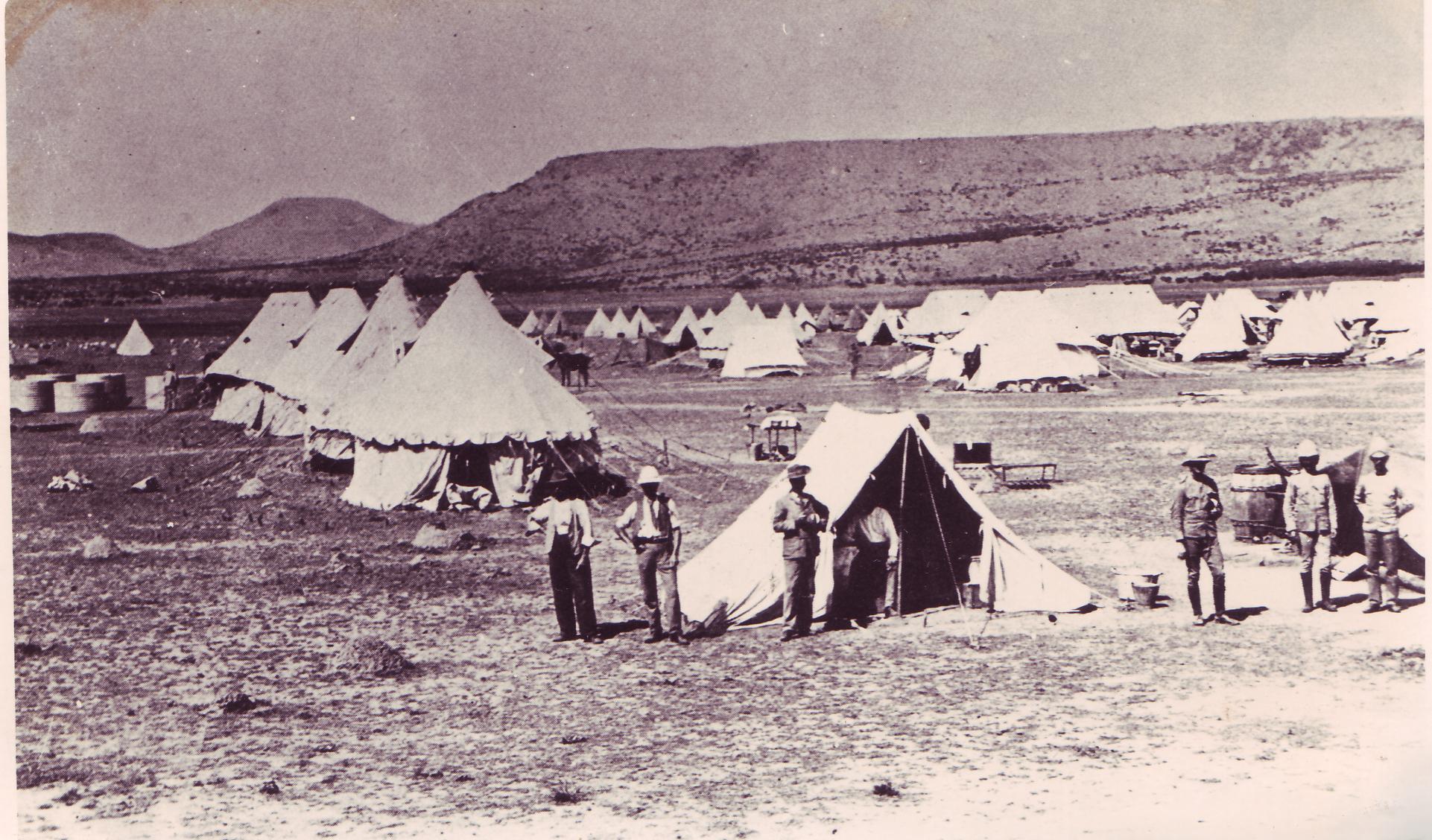

Ladysmith Intombi Hospital (Talana Museum)

Ladysmith Intombi Graves (Talana Museum)

18 January 1900 (HWN)

The market quotations at this evening’s auction were fluctuating. Eggs sprang up from a guinea to 30s. a dozen. Jam started at 30s., the 6lb jar. Maizena was 5s. a pound. On the other hand tobacco fell. Egyptian cigarettes were only 1s. each and Navy Cut went for 4s. an ounce. During a siege one realises how much more bread, meat and water is required for health. Flour and trek-ox still hold out, and we receive the regulation short rations.

Yet there is hardly one of us who is not tortured by some internal complaint, and some die simply for want of common little luxuries.

In nearly all cases I have been able to cure a man with a little variety. I had in store or could procure – rice, chocolate, cake, tinned fruit or soups. I wonder how the enemy are getting on with their biltong and biscuit.

19 January 1900 (HWN)

Colonel Stoneman, having discovered a hidden store of sugar, was selling it at the fair price of 4d. a pound to any one who pledged his word that he was sick and in need of it. Round clustered the innocent shop keepers with sick and sorry looks, swearing by any god they could remember that sugar alone would save their lives, paid their fourpences, and then sold the stuff for 2s. outside the door.

25 January 1900 (HWN)

Eggs tonight reached 30s.6d. per dozen; a suckling pig 35s.; a chicken 20s. In little over a week we shall have to start killing our horses because they will have nothing to eat.

26 January 1900 (HWN)

Our hunger is increasing. Men and horses suffer horribly from weakness and disease. About 15 horses die a day, and the survivors gasp and cough at every step or fall helpless. Biscuits were issued tonight instead of bread, because flour is running short.It is believed that not 500 men could be got together capable of marching 5 miles under arms, so prevalent are all diseases of the bowels. As to luxuries, even the cavalry are smoking the used tea leaves out of the breakfast kettles. “They give you a kind of hot taste” they say.

27 January 1900 (HWN)

Even on biscuit and trek oxen we can only live for 32 days longer, and nearly all the horses must die. The worst is that in their sickness and pain the men could hardly resist another assault. The sickness of the garrison is not to be measured by hospital returns, for nearly everyone on duty is ill, though he may refuse to “go sick.”

The record of Intombi camp is not cheering. The total of military sick today is 1861, including 828 cases of enteric, 259 cases of dysentery, and 312 wounded. The numbers are slightly diminished lately because, an average of 14 a day have been dying, and all convalescents are hurried back to Ladysmith. The number of graves down there is now 282 for men and five for officers, but deaths increase so fast that long trenches are dug, and the bodies laid in two rows, one above the other.

28 January 1900 (HWN)

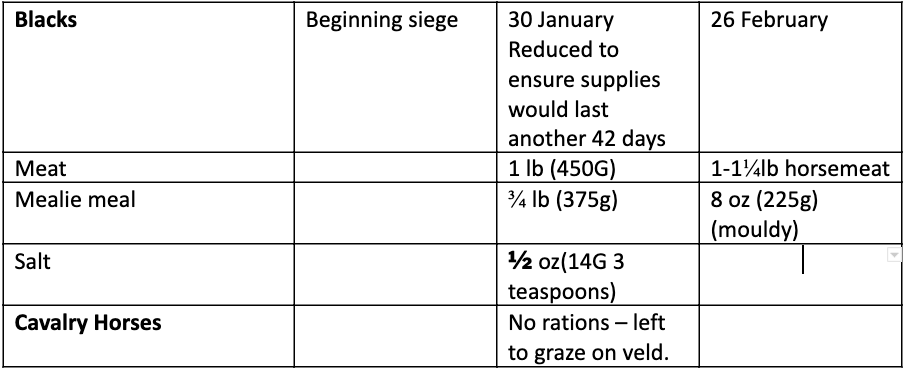

In the morning a consultation was held on the condition of the cavalry horses. At first it was determined to kill 300, so as to save food for the rest, but afterwards the orders were to turn them out on to the flat beyond the race course, and let them survive if they could. The artillery horses must be fed as long as possible. The unfortunate walers of the 19th Hussars will probably be among the first to go. Coming out straight from India they were put to terribly hard work on landing, and have never recovered. Walers cannot do on grass which keeps local horses and even Arabs fat enough.

Because their lives depended on their mounts many soldiers formed strong emotional bonds with their horses. Watkins-Pitchford, one of whose tasks, was to ride our each morning and select the horses to be shot for food (between 70-100 per day) , found the task extremely harrowing.

Horses shot for meat rations during the Ladysmith siege (Talana Museum)

29 January 1900 (HWN)

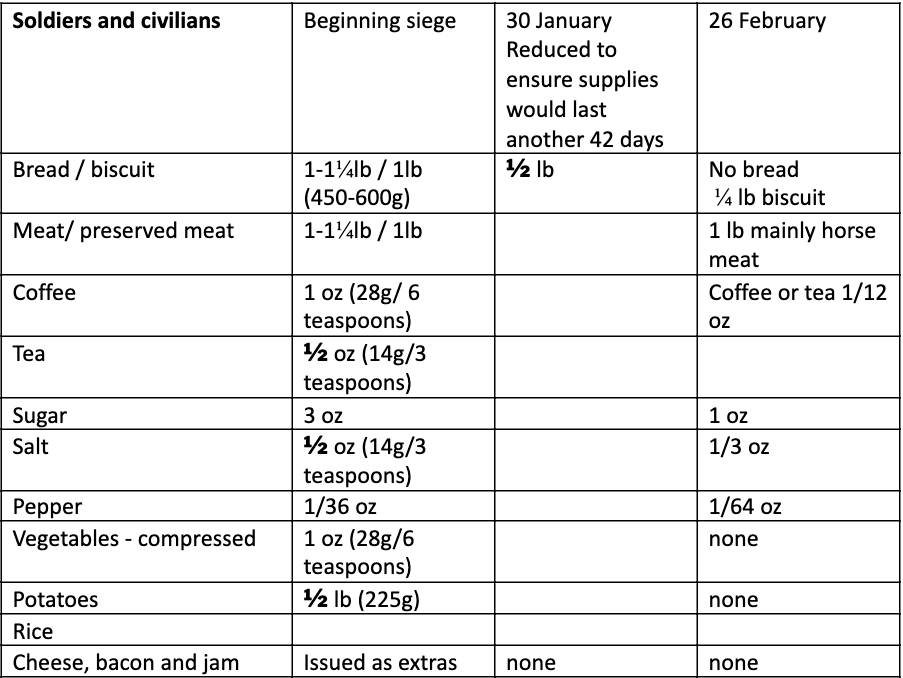

Rations were again reduced today to the following quantities: tinned meat ½ pound, or fresh meat 1 pound; biscuit ½ pound or bread 1 pound, tea 1/6th oz, sugar 1 - 1½ ozs, salt ½oz and pepper 1/36 oz.

It has also been decided to turn all the horses out to grass, except the artillery, three hundred from the cavalry, 70 officer’s chargers, and 20 engineers draught. These are to be kept fed with rations of 3lbs of mealies, 4 lbs of chaff, 16 lbs of grass and 1-1½ oz of salt. The artillery horses will get 2lbs of oats or bran. In the Imperial Light Horse they are killing one of their horses every other day, and eating him.

30 January 1900 (HWN)

The depression (among the soldiers and the civilians) probably arose from the reduction of rations. The remaining food has been organised to last another 42 days…

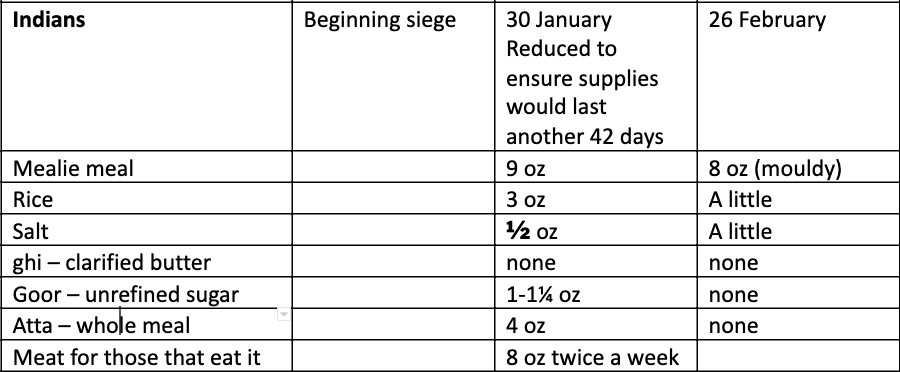

One of the chief difficulties now is the body of Indians – bearers, sais, bakers, servants of all kinds – who came over with the troops, and will not eat the sacred cow.

Out of about 2000 only 487 will consent to do that. The remainder can only get very little rice and mealies. Their favourite ghi, or clarified butter, has entirely gone, and their hunger is pitiful. The question now is whether or not their religious scruples will allow them to eat horse. Many of us have been eating horse today with excellent results.

But one of the most pitiful things I have seen in all the war was the astonishment and terror of the cavalry horses at being turned loose on the hills and not being allowed to come back to their accustomed lines at night.… One met parties of these poor anatomies of death, with skeleton ribs and drooping eyes. At seven o’clock two or three hundred of them… tried to push their way to the cavalry camp, where they supposed their food and grooming… were waiting for them as usual. They had to be driven back by mounted Basutos with long whips, till at last they turned wearily away to spend the night upon the bare hillside.

The cold and wet of the night brought on a terrible increase in dysentery, and I never saw men look so wretched and pinched. When officers in high quarters talk so magnificently about the excellent spirits of the troops, I wish they had… time to visit the remnants of the battalions defending the hills - out in cold and rain all night, out in the blazing sun all day, with nothing to look forward to but a trek ox or a horse stewed in unseasoned water, two biscuits or some sour bread, and a tasteless tea, generally half cold. No beer, no tobacco, no variety at all.

To me one of the highest triumphs of the siege is the achievement of MacNaulty, a young lieutenant in the Army Service Corps. For nights past he has been working in the station engine shed at an apparatus of his own invention for boiling down horses into soup. After many experiments in process and flavouring, and many disappointments, he has secured an admirable essence of horse.

Army service corps (Talana Museum)

Mr Lines, the town clerk, who has quietly stuck to his duties in spite of the confusion and shells, gave me details today of rations allowed to civilians. This does not include the civilian at Intombi, whose numbers are still unpublished. Practically all civilians are drawing rations, for which they apply at the market between 5 and 7pm. They get groceries, bread or biscuit, and meat in the same quantities as the soldiers. Children under 10 receive half rations. Each applicant has been recommended by the mayor or magistrate… I suppose the promise to pay at the end of the siege is only a nominal formula.

At the end of January Donald MacDonald, correspondent for the Melbourne Argus recalled that “Everyone was back on half supplies and the disappointment was borne manfully. We got to the last stocks, the hard biscuit and tinned beef, which, with some course and mouldy mealie meal, stood between us and starvation… the men for the most part gaunt and gloomy, worn down by want of proper and sufficient provisions and the ceaseless manning of the rifle ridges.”

Donald MacDonald (Talana Museum)

The following was recorded by a correspondent for Daily News in one of a series of letters published after the siege was over.

- February 1. It has come at last. Horseflesh is to be served out for food, instead of being buried or cremated. We do not take it in the solid form yet, or at least not consciously, but Colonel Ward has set up a factory, with Lieutenant McNalty as managing director, for the conversion of horseflesh into extract of meat under the inviting name of Chevril. This is intended for use in hospitals, where nourishment in that form is sorely needed, since Bovril and Liebig are not to be had. It is also ordered that a pint of soup made from this Chevril shall be issued daily to each man. I have tasted the soup and found it excellent, prejudice notwithstanding.

- February 3. Horseflesh was placed frankly on the bill of fare to-day as a ration for troops and civilians alike, but many of the latter refused to take it. Hunger will probably make them less squeamish, but one cannot help sympathising with the weakly, who are already suffering from want of proper nourishment, and for whom there is no alternative. Market prices have long since gone beyond the reach of ordinary purses.

2 February 1900 (HWN)

We were shot at rather briskly all day by the enemy’s guns. The groups of wandering horses were a tempting aim. The poor creatures still try to get back to their lines, and some of them stand motionless all day, rather than seek grass on the hills. Many are lost, some stolen, and more die of starvation and neglect. An increasing number are killed for rations and today 28 were especially shot for the chervil factory. I visited the place this afternoon.

Into other engine pits cauldrons have been sunk, constructed of iron trolleys without their wheels, and plastered around with clay. A wood fire is laid under the cauldrons, on the same principles as in a camp kitchen. The horseflesh is brought up to the station in huge halves of beast, run into the shed on trucks, cut up by the blacks, who also pound the bones, thrown into the boiling cauldron, and so “Farewell my Arab Steed!.”

There is not enough hydrochloric or pepsine (the principal enzyme involved in protein digestion) left in town to make a true extract of horse, but by boiling and evaporating, the strength is raised until every pint issued will make 3 pints of soup. A punkah (a type of ceiling fan) is to be fitted to make the evaporation more rapid, and perhaps my horse will ultimately appear as a jelly or a lozenge. But at present the stuff is nothing but a strong kind of soup, and the first issue today the men had to carry it in the ordinary camp kettles.

Every man in the garrison tonight receives a pint of horse essence hot. I tasted it in the cauldron, straight from the horse, and found it so sustaining that I haven’t eaten anything since. The dainty blacks and Colonial Volunteers refuse to eat horse in any form. But the sensible British soldier takes to it like a vulture, and begs for lumps of the stewed flesh from which the soup has been made. With the joke “Mind that stuff, it kicks” he carries it away.

On 5 February horse sausage was issued for the first time.

7 February 1900 (HWN)

The organisation (of issuing rations) is admirable, but one feels it comes a little late in the day. The same is true of the biscuit tins which are put up as letter boxes about the camp for the local post, and of the new plan of making sandals for the men out of flaps of saddles and the buckets of cavalry carbines (after all these would not be needed with the deaths of the horses). For a fortnight past, 120 of the Manchesters have gone barefoot among the rocks.

Lieut Col B W Martin of the Natal Volunteers commented on 11th February that they were “compelled to partake of horseflesh and its derivative “Chevril”. It was not a pleasant experience but “needs must when the devil drives.” I well remember the nausea that overcame me when I had my first taste of horseflesh!” He then continues and mentions that “Field Marshall Lord Chetwolds, an officer of the Cavalry Regiments, who served in Ladysmith during the Siege, often claimed that the Cavalry were responsible for the long stand of the besieged garrison, by reason of the fact that they provided the food that sustained the garrison.”

17 February 1900 (HWP)

It is difficult for hungry men to reasonable…. Day by day the quantity and poor quality of the food are more apparent. Everybody is growing gaunter and less able to exert himself.

Some short time ago I saw a very significant sight as I was riding out for an afternoon’s ride. A horse – a scarecrow of a beast – had died on the veld, and as I rode in among the thorn trees I came across two poor Tommies hacking off pieces of its flesh with their clasp-knives. They looked very guilty and confused when I rode up, evidently thinking I should take some notice of their action, but I had nothing but commiseration in my heart for the poor fellows driven to such straits.

A week or so ago we bought up all the starch we could get in the stores, some blue starch and some buff, sold by Ricketts for lace curtains. This has been made in blancmange as the occasion require… when I enquired how it had been appreciated…. I was told it had “Done fine”, which exactly expresses our condition. As long as the food can be swallowed that is all that is needed…

On the 9th February Arthur Crosby of the Natal Carbineers noted that their “rations – plate of mealie meal porridge with tea, spoonful of sugar, slice of bread for breakfast. Chevril soup (made from horse flesh), slice of bread and tea for dinner, soup, bread and tea for supper”. On 11th Feb he records “much distressed to find our rations cut down again. We now get ½lb bread, 1oz sugar and a pint of chervil and tea for the day – not sufficient for one meal….It is gradual starvation.”

26 February 1900 (HWP)

As I was riding out to the Camp (called Tin Camp from its being built of corrugated iron) about a mile and a half from the town to examine a number of horses for next day’s consumption… I rode on to inspect the few remaining horses left of our once smart cavalry regiments. It was pitiable to see the poor brutes in the last stages of emaciation and poverty, ”the gum down-roping from their pale-dead eyes” standing listlessly with hanging heads and knuckling fetlocks.

They were penned in an enclosure formed by stretching wires across from one long iron building to the end of the next one lying parallel to it. These rooms, or sheds, were riddled with shell and rifle fire, the windows shattered and the roofs and walls perforated by the shrapnel which the enemy flung into the camp supposing, at any rate during the first part of the siege, that it was occupied by troops. Here the poor beasts stood, waiting for the morrow’s bullet which was to end their suffering but not their usefulness.

Two had actually fallen dead from exhaustion since being penned in an hour previously. This was our meat supply and as I walked around the poor starved brutes the iron of the siege entered into my soul and helped me to realise – if further realisation were necessary – the straights to which we had come. And yet even this poor source of food was failing!

28 February 1900

In a letter a Highland officer mentioned that the Boers were moving off and that “it made one very angry to think that we had no cavalry nor artillery in a fit state to go after them-most of our cavalry horses having been eaten and the artillery horses too weak from want of food to pull a gun.”

Other excerpts from letters (From Letters from Ladysmith edited by Edward Spiers) recorded by Pvt A Campbell “… went up to Caesaer’s camp to join the Manchester Regt… and found them a regiment of living skeletons - and no wonder. They were living on 1½ biscuits per day and mule flesh.”

Cpl J F Crompton noted that the Relief column “was just in time, for we were all dying almost from want of food, for we had been living on horse and 1 biscuit per day and living out in the rain all night and dried again by the sun…”

Pte Hillsay of the 19th Hussars remembered that… We had 480 horses in the regiment… at the commencement of hostilities. We had 60 when we were relieved….”

29 February 1900 (HWP)

(The day after the relief) A column was sent out in pursuit of the retiring enemy, who were reported as having got all their guns away as far as the railway terminus at Pepworth station. Thither we followed as quickly as possible, which was indeed but very slowly. Men and horses were “done” and we could hardly get the field guns along at all…. We did our best but it was a very poor best. Going up a slight rise out of the town the artillery horses dropped exhausted in their traces.

On the day Ladysmith was relieved there was only sufficient food for another 4 days. Despite intensive research I have been unable to find any record of the number of horses that survived the siege.

Scale of rations during the siege

In December all milk was reserved for the sick and eggs were also requisitioned for the sick only. On 21st December all cows were commandeered for the hospitals.

Food prices throughout the siege (prices in brackets have been calculated at what the value paid in 1900 would be worth in British pounds today – and then you can calculate at the current exchange rate to get a price in Rands – exorbitant doesn’t come close to describing it!).

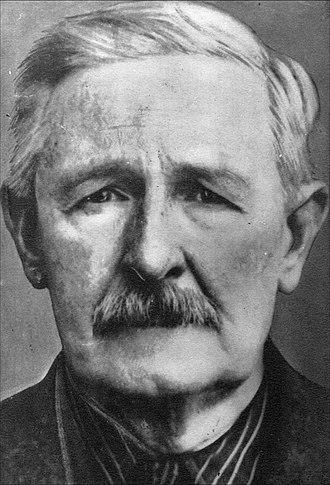

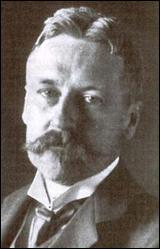

Herbert Watkins-Pitchford

Born on 3 June 1868 in Tattenhall in Cheshire, he studied at the Royal Veterinary College, London graduating in 1889. In 1896, he served as Principal Veterinary Surgeon to Natal Colony. In the same year, with Arnold Theiler, he was the first to create a successful vaccine against cattle rinderpest.

In 1898 he was promoted to Director of the Department of Disease Research and in 1901 to Government Bacteriologist and Director of Veterinary Services for Natal. He was stationed in Dundee shortly before the outbreak of the Anglo Boer War, but was caught up in Ladysmith and recounted his experiences of the siege in this letter. For his services during the war he was awarded the Queen's South African medal with two bars.

In 1903 he became Director of the Natal Museum. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, Edinburgh (FRSE) in 1906. In 1909 he initiated establishment of the Natal Veterinary Medical Association and served as its first president. After the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, he hoped to be appointed Director of Veterinary Services, but instead, this post went to his colleague, Arnold Theiler.

Although offered the post of Deputy Director, he left South Africa. In 1912 he returned to England to join the British Army. At the outbreak of the First World War he became a Lt Colonel in the Royal Army Veterinary remount Commission overseeing horse conscription and inspection. He was awarded Companionship of the Order of St Michael and St George (C.M.G) in 1918 for services rendered during the First World War.

In 1922 he became Commander of the Army Veterinary School in Aldershot.

After his retirement in 1935 he returned to South Africa, where he died on 25 June 1951 in Illovo on the south coast of Natal.

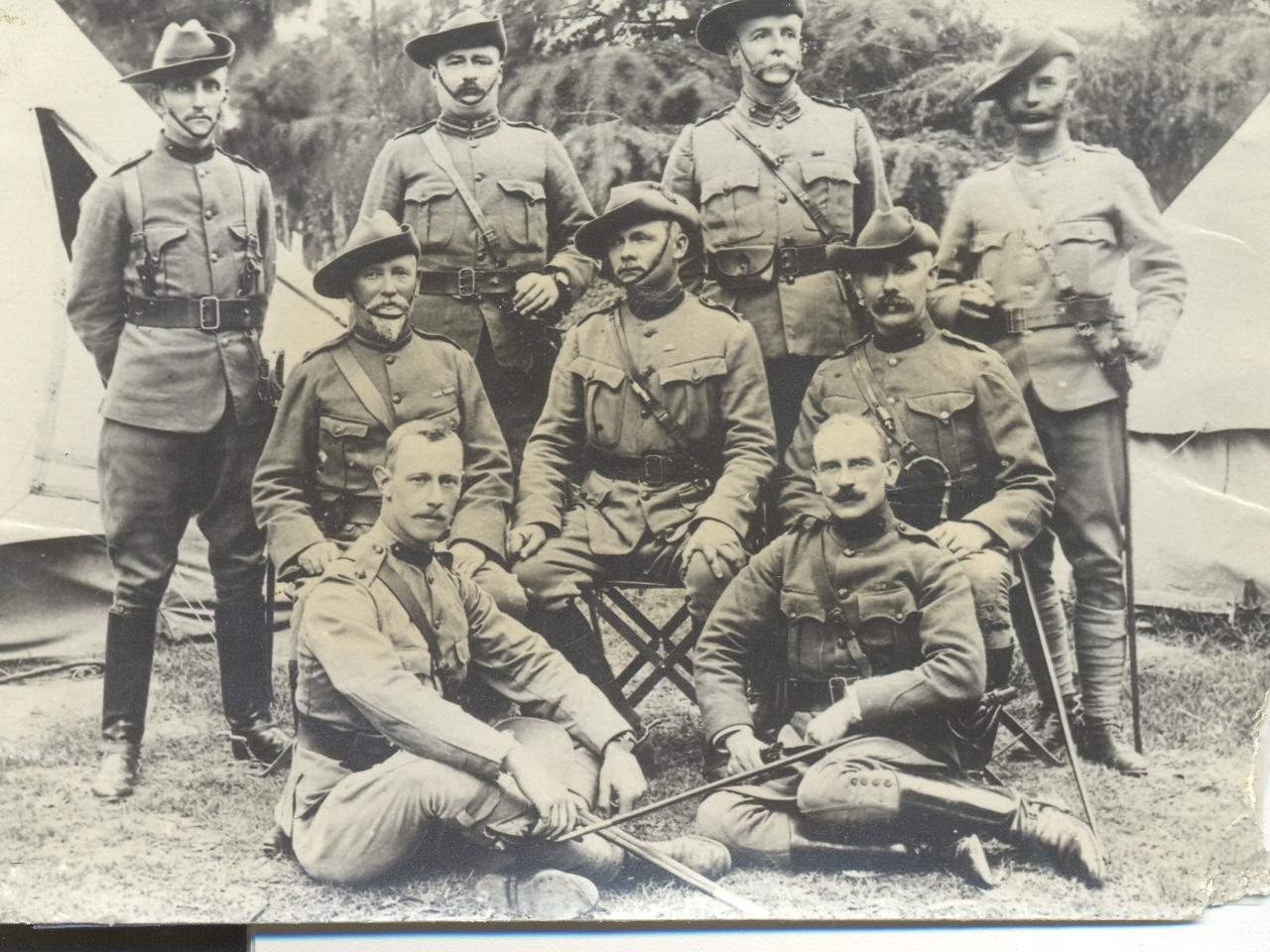

Herbert Watkins-Pitchford seated centre (Talana Mueum)

Henry Woodd Nevinson

Men who knew Nevinson said that "As a war correspondent Nevinson was always scrupulously careful in gathering his facts, and his writing often inspired those struggling towards freedom." Over the next few years he developed a reputation as an outstanding war reporter." Nevinson was opposed to the war and he wrote in his diary that Britain's "real objects were to paint the country red on the map and to exploit the gold-mines."

He arrived in Ladysmith on 5th October. Later that month he witnessed "Black Monday" when over 800 men were taken prisoner after an engagement extending about fifteen miles from Nicholson's Nek. In expectation of Boer attacks on the town, the British forces organised and constructed defensive lines around the town. The Siege of Ladysmith lasted 118 days until 28th February 1900. Nevinson's account of the siege first appeared in The Daily Chronicle. Later that year Methuen published his Ladysmith: The Diary of a Siege.

Henry Woodd Nevinson (Talana Museum)

Number of deaths recorded for the siege of Ladysmith

Soldiers Killed in action - 211, died of wounds - 59, died of disease 563. Total 833 (6,2% of the strength of the Ladysmith garrison). Civilians died during the siege 54 (this was 0.8% of the population).

During the siege, the number of beds in the hospital camp grew from the initial 100 to a total of 1900. A total of 10,673 admissions were received and treated at Intombi. One train per day was allowed to carry wounded from Ladysmith to Intombi. William Watson who kept a diary during the siege commented on 19 February that “ Old horse and ship’s biscuits, are not the right food for sick people.”

At the beginning of March there were 2 800 ill and wounded in Ladysmith. Intombi hospital had 11 135 patient admissions.

Pam McFadden has spent many years researching the battlefields of KwaZulu-Natal. She has been interested in them since a young child. As a registered specialist guide on these battlefields for the past 40 years her knowledge about events and the people involved is considerable. Since 1983 as curator, Pam McFadden has developed the Talana Museum in Dundee into one of the finest in the country. As part of the museum collections she has collected and created an extensive museum archive, that holds many treasures.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.