Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Born in Palermo on 1st October 1910, Giuseppe Maniscalco was one of a large family of 8 children. After the sudden death of his father, his mother was unable to support the children alone and therefore decided to leave Palermo and travelled to family and friends in Trapani. With the consent of Giuseppe's mother, the children were split up and were adopted by other friends and relatives.

Giuseppe decided he would like to live with his uncle, Rizzuto Noncencio, who had a farm near Casablanca, in Morocco. His uncle traded in mules and horses, introducing stallions from the Abda and Chianda areas of Morocco, to improve the strain of Sicilian horses. All went well with Giuseppe until one day he had a traumatising experience involving the foreman, Mr. Poleo, who was unsuccessfully herding some animals into an enclosure. Frustrated, he told Giuseppe to stand at the main gate, waving his arms while he herded them in from behind. The animals stampeded towards him and he took fright and ran away. He hid in the bush and was rescued by 2 Arabs on camels who took him to their village. He spent a week with them, not understanding anything they said.

As no one had come to try and find him from his uncle's farm, he decided to run away again and made his way to the farm of Mr Pietro Mazzara, a Sicilian who had been farming in Morocco for many years. This family adopted Giuseppe and soon he was attending a school where he also learnt French and Arabic. After World War I Pietro Mazzara's business expanded. He was exporting wildlife skins to the USA. In 1929, tragedy struck and Pietro Mazzara was killed in a train accident in the USA. His wife had to sell the farm and together with her daughters and Giuseppe they returned to Sicily. He did 18 months of military service and married Anna Mazzara. Six months after the birth of his son, the Italian Govemment issued orders for him to report for intensive military training and he was subsequently sent to Eritrea. His family was left behind. This was the last time Giuseppe was to see Italy for the next 33 years. His wish to return to Africa had been granted, but not in the way he had envisaged.

The war in Eritrea and Ethiopia was soon ended when the South Africans and the English liberated the area. He was interned with other Italian soldiers from the Sudan at Decamere, about 40 km from Asmara. They were informed by an English Major that, if they wished to stay in the country, they would be given 14 days to seek work or they would have to remain captives of the British military. Boarding a truck, he travelled to Asmara, where he frantically searched for work in vain. Tired and weary, he entered Caffé Rialto on Viale Mussolini. He met an old Sicilian friend, Carlo Giacaloni, whom he had not seen for many years. After reminiscing, they finally got down to talking business. Carlo had a very well maintained Fiat truck and Giuseppe suggested that they could use it to trade with livestock in Ethiopia where there was an open market.

The first three trips went well and they were already making some profit. On the fateful 4th trip, being told by an Australian Sergeant not to enter Ethiopia without a military escort, they decided to ignore his warning and go it alone. Near the top of a mountain, they were suddenly fired upon by a group of bandits (shifta) and Carlo was killed instantly. Giuseppe flung himself out of the passenger side of the vehicle and ran for cover. The two passengers at the back also jumped off and were never seen again. After hiding for most of the day, he climbed down into the valley and found Carlo's body still in the vehicle. With great diffìculty, he pulled him out of the truck and buried him. He retrieved his suitcase and the 300 pounds they had made as profit and with his bush hat and large hunting knife as his only protection, he decided to start walking towards the Sudan.

He had no intention of returning to Italy because of his royalist leanings and had also no intention of being behind barbed wire in an internment camp at the pleasure of the British. To continue his journey he had to avoid walking in British controlled areas. On his way into Sudan, he was briefly held captive by the ruthless native chief Oman, who accused him of killing a dog belonging to one of his tribesmen. In fact, Giuseppe was attacked by the dog and was forced to defend himself. Fortunately, Giuseppe found a friend in Oman's tutor, an older and wiser man, who eventually arranged an escort to help him escape and to show him the way safely onwards.

On the White Nile he came across a rhinoceros who chased him. He dropped what he was carrying and ran. Seeing a large boulder ahead, he ran directly for it. He swerved at the last minute and the rhinoceros, short sighted and at full speed, hit the rock and was knocked out.

In the Congo, after unsuccessfully trying to enter Angola, he met a friendly Belgian who sold him a rifle and ammunition. Up to this time, Giuseppe had been using a knife and a spear to hunt and fish for food. It was also here that he learnt that the Allied forces were occupying France. In the Congo, with its wet and hot tropical climate, he contracted the dreaded malaria disease and was nursed back to health by local tribesmen who used natural herbs and medicines. In Katanga he was almost arrested because a farmer, whilst pretendlng to be sympathetic, reported his presence to the local police. Giuseppe, instinctively mistrusting the farmer, decided to move on before his return. From a nearby hill, he saw the farmer and the police arriving. His instinct had been correct.

Entering Zambia (then Northern Rhodesia), he befriended a farmer called De Wet, who told him that this territory was a British colony and so he decided to walk towards Mozambique as quickly as possible. He crossed the Zambesi river in a log boat manned by tribesmen and headed for Beira. He was told by a railway clerk, Michel, that his best bet was to see a Mr. Mattinoti, an Italian farmer who had already employed 3 Italian ex soldiers on his farm. On arrival he met these three. He was surprised to hear that it was 1946 and the war had already ended.

Unsuccessfully Mr. Mattinoti tried to employ him, but the Mozambique authorities were under orders from their government not to allow any ex prisoner of war to remain in their territory. They informed Giuseppe that he was to report to the immigration office at a later date on notification, and would be put on board a ship and repatriated back to Italy. Until such time, he could remain free but under supervision of a police detective. Whilst in a shop, the detective picked up conversation with a young Portuguese woman, and Giuseppe, seeing a bus arriving outside, decided to take his chance, and boarded it. He eventually arrived at Michel's house and his wife Maria found him a suitable hiding place on the grounds of their farm. On Michel's return from work and with a mischievous twinkling in his eyes, he told Giuseppe and his wife that they were going to see a movie in the town. He told Giuseppe to shave off his beard and that he would give him a change of clothing. On arrival at the cinema, the police detective, who had been Giuseppe's escort, was also present and at one stage was at Giuseppe's back talking to his associates. Giuseppe was not recognised. Later, during this period, Giuseppe was eventually stopped by the Portuguese area Kommandant, who detained him. Giving the surety that he would leave Mozambique within 3 days, he was allowed to depart and continue his joumey. Remembering the words of a South African farmer in the Beira area, Mr. Strydom, whom he had befriended, he decided that South Africa would be a safer destination.

He followed the route of African aspirant mine workers who were heading towards the camp of the labour consultant in Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia). On arrival at the labour transit point, he met a friendly Scotsman, Mr. McMaster, who was prepared to offer him employment after hearing the story of his amazing travels thus far. Giuseppe had made up his mind to enter South Africa and therefore refused this proposal.

On crossing the Limpopo River with the black work seekers, the labour official on the South African side was surprised to see a white man walking amongst them. Giuseppe once again, as he had done many times before, told the official of his incredible journey. The official then promised him safe passage and transportation to Louis Trichardt (a South African town). On arrival at Punda Maria, a town much before Louis Trichardt, the driver stopped outside the police station. They had been notified of Giuseppe's arrival by the labour official and arrested him immediately. He was transferred to Sibasa and eventually through Louis Trichardt to Pretoria by rail. On arrival he was thought to be an escapee from Zonderwater Prisoner of War Camp. No one believed his story, including the Italian inmates at Zonderwater. They called him "Il Matto". Fortunately for Giuseppe, he was interviewed by an official of the department of immigration by the name of Johannes (Jack) Van Der Spuy, who had spent some time in ltaly during World War 2 as an airforce Intelligence officer and who spoke ltalian fluently. In his own words, Jack, when seeing Giuseppe, was reminded of the Jewish prisoners of war in the Buchenwald camp. His face was horribly sunken and his body was skin and bone. His clothes were hanging on their last threads. Giuseppe was 1.82 meters tall and had immense hands. Looking at his shoes, Jack noticed that only the upper part was left and his feet were bloody. The look in his eyes showed tremendous strain and he was somewhat like a wild animal looking for someone to care for him, to understand his predicament and mainly to believe him.

Remains of the World War II inner wire fence at Zonderwater (Peter Spargo)

Because Giuseppe had no identification papers, the Italian Consulate informed Jack that they were not interested in him at all. Jack took a deep personal interest in his case. What also surprised him was the accuracy with which Giuseppe could throw a knife and spear. When his knife hit a tree trunk it required great strength to retrieve it. On the medical examiner's report, Giuseppe showed signs of one who had travelled in a tropical area and had contracted malaria. Once Jack's report was finalised, he and Giuseppe were summoned to the office of his superior, Mr. J. Basson. On seeing Giuseppe and hearing his story, he was so amazed that he withdrew a one pound note out of his pocket and instructed Jack to see that Giuseppe be given a decent meal and a haircut. Giuseppe was then transferred to a farm outside Pretoria in order to recover more fully.

At the Control Board headed by tha Secretary of Immigration in Pretoria, it was decided unanimously that Giuseppe could stay in South Africa. They went so far as to find him employment in the carpentry section of the giant steel works, ISCOR, in Pretoria. Giuseppe had in the meantime written to his wife Anna in Italy, who had been notified nearly three years previously by the International Red Cross, that he had died in the truck accident in Ethiopia. She had therefore started a new life and had no intention of joining him in South Africa. He himself started a new life and was granted a divorce from Anna and subsequently married Maria Anjos, a lady of Portuguese descent who already had a son from a previous marriage. He raised her son as if he was his own and they together had another 3 children, 2 girls and a boy.

It took 33 years for Giuseppe to return to Italy and there he saw his son, whom he had last held in his arms as a small baby before he had gone to Eritrea to do his military service.

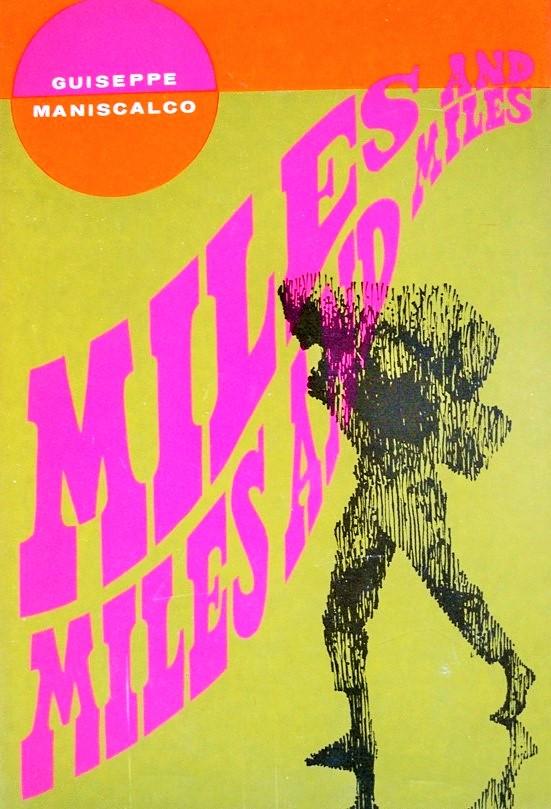

In 1968 his book was published in South Africa entitled "Miles and Miles and Miles" with a further publication in England with the title "The Long Walk".

Book Cover

Giuseppe's ambition was to do this incredible journey once more, but due to chest pains which plagued him later in life, this was not possible. He died in Pretoria on 28 January 1974, gone but not forgotten: the only man who lived to accomplish this long adventurous journey through Africa on foot, taking on the hazardous environment and the dangers from man and beast and dodging all other obstacles thrown in his way.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.