Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In 2021 the Carnegie Corporation of New York celebrated its 110th anniversary. Perhaps this is sufficient reason to remind readers of the generous philanthropic endowments first made by Andrew Carnegie and thereafter by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, to South African libraries during the early years of the twentieth century.

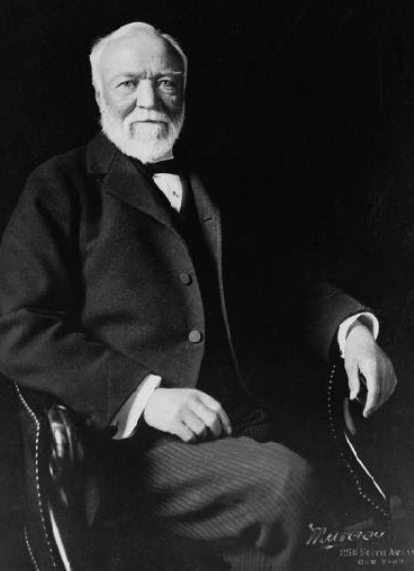

Andrew Carnegie Portrait (Bill of Rights Institute)

In 1906, Vryheid became the first South African town to receive a financial grant from Andrew Carnegie for the establishment of a public library. By 1917, when the last endowment was made for a similar library in Krugersdorp, twelve South African towns had received financial assistance, totaling the not insignificant amount of $123 855, to establish free library services to their local communities.

These twelve libraries served their local communities faithfully for the next 35 years, until the promulgation of the Separate Amenities Act of 1953, limited their use to the White population only. By the early 1970’s, overtaken by a combination of demographic and technological developments, five of these old buildings had reached the end of their lifespan and were demolished. Fortunately, one hundred years later we can still admire and enjoy the remaining seven of these fine Edwardian buildings.

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie had a very personal interest in libraries. Being a ‘self-made man’, having made his considerable fortune in the American steel and railway industries, his formal education ended when he was merely 12 years old. But he remained eternally grateful of the opportunity as a boy to use the private library of Colonel James Anderson in Allegheny, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1904 the unveiling of a statue to Col. Anderson, commissioned by Andrew Carnegie, took place outside the Carnegie Free Library of Allegheny.

Anderson Monument near Carnegie Library (Wikipedia)

From his own early experience, Carnegie decided there was no better use to which money could be applied for the benefit of boys and girls than the founding of a public library in a community, which was willing to support it as a municipal institution.

His philanthropic donations commenced in 1881 with the gift of a library to the town of his birthplace, Dunfermline, Scotland. But as his personal fortune flourished, he extended his library-giving programme at home and abroad. Subsequently, the Carnegie Corporation donated some $56 million to erect 2509 public libraries across the globe.

The usual practice was to donate money for a building on the condition the community or municipality provided a suitable site and annual funding to maintain a free public library. Of the 2509 ‘Carnegie Libraries’, of which incidentally less than one third bear the Carnegie name, 1681 were built in the USA, 660 in the UK, 116 in Canada, 18 in New Zealand, 12 in South Africa, 6 in the Caribbean, 4 in Australia and 1 each in Mauritius, Fiji and Seychelles.

Dunfermline Carnegie Library (Wikipedia)

During the first 29 years of grants made by Andrew Carnegie, the design of the library buildings was left solely to the discretion of the recipients.

Many of the early library buildings in the US and UK were rather ornate, often consisting of two storeys and a basement. Club rooms and auditoriums were frequently included to provide rental income to offset the operating costs. Later the Carnegie Corporation refused to approve plans that included rooms for non-library use. In 1910 James Bertram, the private secretary of Andrew Carnegie drew up general specifications to be adhered to by architects when designing library buildings for Carnegie grants. He argued that the domes, marble, and fancy architectural embellishments did not provide the space needed for library services and only served to increase building costs.

The Carnegie Libraries in South Africa

The Carnegie Libraries in South Africa were erected in twelve towns scattered across the country and the grant amounts ranged from $4 385 in Barberton to $26 470 in Germiston.

The recipient towns, in chronological order were:

- Vryheid, 1906, $7 300, Building still extant in Market Street. Now Information Bureau.

- Harrismith, 1907, $9 825, The Harrismith Town Hall is still extant but no longer houses the library.

- Hopetown, 1908, $4 850, Building still extant at corner of Van Riebeeck Street and Van Riebeeck Avenue, but vacant and somewhat dilapidated.

- Muizenberg, 1909, $7 800 Building still extant in Main Street, Muizenberg. Now a Police Museum.

- Barberton, 1911, $4 385, Only façade remains.

- Standerton, 1911, $7 300, Status unknown. Building probably erected in the then Market Square.

- Moorreesburg, 1911, $7 290, Building still extant. Now Tourism Bureau.

- Potchefstroom, 1912, $12 175, Building still extant in Walter Sisulu Street. Now office of the Municipal Speaker.

- Benoni, 1913, $13 330, Building demolished during the 1970’s.

- Newcastle, 1913, $7 290, Building still extant. Until recently an Art gallery.

- Germiston, 1915, $26 470, Facade incorporated into Dumisani Masilela City Theatre.

- Krugersdorp, 1917, $15 840, Building demolished in the 1970’s and replaced with new library on same site in Luipaard Street.

It is interesting that two of the library buildings erected prior to 1910, namely Vryheid and Muizenberg, contain decorative but non-functional cupolas, whereas they are absent in the later buildings. This may well have been due to the design requirements laid down by James Bertram.

Let us now discuss each of the buildings in turn.

Vryheid Carnegie Library

Vryheid and the Nieuwe Republiek (New Republic) was established in 1884 on land donated by Dinizulu to Voortrekkers who assisted him in suppressing other contenders to the Zulu throne. In 1888 the New Republic’s request to be integrated with the ZAR was granted and in 1903 the area was annexed by the Colony of Natal.

In a letter both flattering and imploring dated 15 December 1905, Andrew Millar the librarian of the small Vryheid library, wrote to Andrew Carnegie at his magnificent Scottish estate, Skibo Castle, stating as a Dunfermline man himself, he too had enjoyed the free public library so generously endowed by Carnegie. Saying the Vryheid White population totaled about 1300 he explained with the Local Board in the throes of street making and other improvements, there were no funds available for a library. Adding that the local library and all the books were destroyed during the late war, he said they were starting afresh. He then stressed the adverse effects of the great local depression and concluded with: ‘There are (sic) a large number of young men in our midst, many of which are Scotch and, in the wintertime, especially after business hours there is no place of amusement for the young man to go, around us an ocean of veldt, the only place of attraction the canteen’.

This heart rendering appeal, plus the Vryheid Local Board’s guarantee to the library of a sum of £100 per annum and the granting of a site on the Market Square to the value of £500, prompted James Bertram on behalf of Carnegie to confirm by letter, dated 6 October 1906, the endowment of £1 500 to erect a free public library.

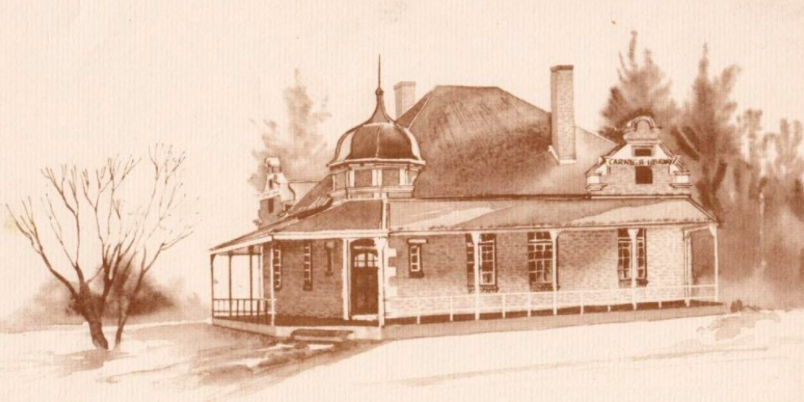

Vryheid Carnegie Library as it would have appeared in 1909

Designed by architect Oscar Rau who skillfully exploited the corner site to arrange access from the street corner to the charming little cupola behind which the reading rooms were placed. Another unusual addition, as far as the South African Carnegie libraries were concerned, were the verandas, which Rau considered essential due to the sub-tropical climate. Constructed by Johannes Lourentz Mouritzen, the building was officially opened on 30 September 1909 by the Chairman of the Town Council J. O. Player.

The library proved so popular that in March 1918, a further application for funding was submitted to Carnegie to enlarge the building with additional lecture rooms because the Vryheid population had increased substantially due to the coal mining in the district. It must have been disappointing to have the application declined by the Carnegie Foundation due to its post war focus on librarian education and training rather than the building of libraries.

Serving as the town’s library until 1976, it was declared a National Monument in 1981. It was fully restored in 1984. At present it houses the Vryheid Information Bureau.

There is unfortunately very little information available on the architect Oscar Rau. According to a brief entry on the Artefacts website, Rau was born in Germany and educated in Breslau, Germany, where he exhibited and won some prizes for drawings. He came to South Africa in 1903 and settled in Vryheid where he practiced until at least 1914. He probably returned to Germany at the outbreak of the First World War, and it is thought that he was responsible for the design of several buildings in Vryheid and the surrounding district.

Harrismith Carnegie Library

Harrismith was established in 1849 and is one of six towns in South Africa named after Sir Harry and Lady Juanita Smith. An older resident assured me in her youth the Town Hall at the rear of the Harrismith Municipal Offices served as the town library.

Front elevation of the Harrismith Municipal Offices and Town Hall

The municipal offices and townhall were designed by architects Agutter & Price. This Pietermaritzburg based partnership lasted from 1906 to 1909 and their main work appears to have been these two buildings.

Since this building was designed at the same time as the Carnegie endowment was made, it seems likely that the grant was applied to fund the construction of the Town Hall, which then also accommodated the free public library.

Doreen Greig attributes the physical construction of the town hall to soldiers of the Imperial Garrison stationed at Harrismith and describes the impressive brick and light-brown sandstone building as one of the best examples of neo-classical work in South Africa.

Harrismith contains several historical buildings dating from the Republican and Edwardian eras, and it is well worth the slight detour from the N3 to view them.

South elevation of Harrismith Town Hall where the Carnegie Library was most likely housed. (Mike & Minette Bell in Artefacts.co.za)

Hopetown Carnegie Library

Strangely enough, the name Hopetown is not linked to the 1867 discovery of the first diamond in South Africa on the nearby farm De Kalk.

This small town situated some 134 kilometers south-west of Kimberley in the Northern Cape, was founded in 1853 on the farm Duvenaarsfontein, owned by S. C. Wiid. The subsequent village was named in honour of Major William Hope, Auditor-General of the Cape Colony and became a municipality in 1858.

The Carnegie Library situated at the corner of Van Riebeeck Street and Van Riebeeck Avenue is currently vacant and somewhat dilapidated. It is an L shaped building, with the wing possibly serving as the library office. The buttresses on either side of the central window, together with the roof molding above the pediment gives the building an ecclesiastical appearance, which undoubtedly was the architect’s intention. Above the entrance appears the proud legend ‘Carnegie Gebou 1909’.

South-western perspective of the Hopetown library. Note the wall buttresses, pediment, and roof molding above the central window providing the building with an ecclesiastical appearance. (Christa Nel)

Muizenberg Carnegie Library

When the railway line reached Muizenberg in December 1882 and soon thereafter extended to Kalk Bay, travelling for holiday makers to the pleasant Muizenberg Beach and warmer waters of False Bay became much easier and relatively inexpensive because of the Cape Government Railways’ offering of ‘picnic special’ trips.

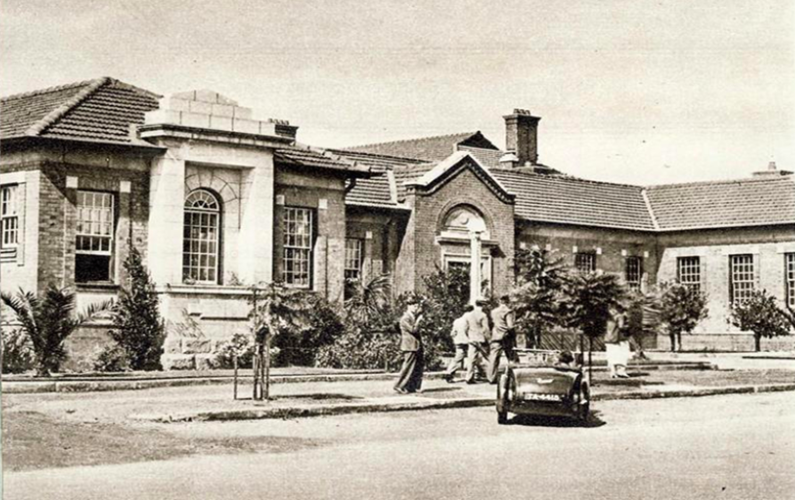

The Muizenberg Carnegie Library in Main Road between the bungalow ‘the Fort’ (now Casa Labia) and the Post Office was designed by architects N. T. (Norris) Cowin & John Lyon and the foundation stone laid in January 1909 by Mayor A. T. Rutter. The library was officially opened on 10 April 1910 by the Honourable (later Sir) Frederick de Waal.

Originally, the white-columned balcony was open to the elements, but later fronted with glass windows to provide additional internal space. Together with the adjacent Post Office building the complex now serves as a Police museum.

After 1911, Cowin moved to Pretoria, where he worked in the Public Works Department, before going into partnership with E. M. Powers.

The Cowin and Powers partnership also designed the Carnegie Libraries at Moorreesburg and Potchefstroom.

Muizenberg Carnegie Library by Cowin & Lyon (SJ de Klerk)

Barberton Carnegie Library

Barberton in the Mpumalanga Province was named in honour of Graham Hoare Barber who discovered a rich gold bearing reef there in 1884. It was administered by a health committee from 1902 and became a municipality in 1904. According to the pamphlet, A Guide to Barberton’s ‘Heritage Walk’, the De Kaap Stock Exchange was the second stock exchange building in Barberton. The building was erected in 1887 but its existence as a stock exchange was short-lived. In 1899 the building was purchased by Sammy Marks and in 1910 the Barberton Municipality took over the building to house the Carnegie Library and first museum. When the building deteriorated to such an extent that it had to be demolished, only the façade could be saved.

Façade of the De Kaap Stock Exchange, later the Carnegie Library and first museum (The Heritage Portal)

Standerton Carnegie Library

Unfortunately, this was the one Carnegie Library I was unable to source any recent information on, which leads me to think the building has been demolished.

On the Carnegie Corporations’ Digital Website, I found a document dated 26 September 1910 signed by one J. C. Pretorius informing the Foundation that the Standerton Municipality has approved a resolution to grant a site on the town’s market square for the erection of a library building. An amount of $7 300 was granted in 1911 by Carnegie to erect a free public library here.

Moorreesburg Carnegie Library

Moorreesburg, 30 kms north of Malmesbury was laid out on the farm Hooikraal in 1879 and administered by a village management board from 1882, until it attained municipal status in 1909.The town was named in honour of J. C. le Fébre Moorrees (1807-1885) minister of the Swartland (Malmesbury) congregation from 1833 to his death in 1881.

This attractive Edwardian Carnegie Library was designed by architects N. T. (Norris) Cowin and E. M. (Ernest) Powers and erected in 1913 in Church Street on land donated by the Moorreesburg Dutch Reformed Church. According to Deirdré Richardson, this library was established due to the diligence and perseverance of Ms M. D. Koch from the farm Biesjesfontein, who initiated the project.

The Artefacts website maintains this partnership between Norris Cowin and Ernest Powers in Pretoria was first listed in 1913. The partnership was formed on winning the competition for the central fire station in Bosman Street, Pretoria in 1912. The partners came second in the competition for the Boksburg Town Hall (1912), and won the competition limited to Transvaal Architects for the Dutch Reformed Church at Greylingstad in the same year, a competition adjudicated by Herbert Baker.

Moorreesburg Carnegie Library, now the Tourism Bureau, designed by N. T. Cowin & E. M. Powers. (Swartland Tourism)

Potchefstroom Carnegie Library

Formerly known as Mooiriviersdorp, Potchefspruit and finally as Potchefstroom (merging the surname of Voortrekker leader A. H. Potgieter and the title ‘chef’ meaning chief) this town was founded in 1838 by Andries Hendrik Potgieter. It became the first municipality in the former Transvaal.

The Carnegie Library in Church (now Walter Sisulu) Street was designed by N. T. Cowin and E. M. Powers and completed in 1911. The library was designed to sympathetically mirror the appearance of the nearby town hall as evidenced by the similarity of the gables and porticos at both buildings. The library now serves as the Chambers of the Speaker of the Municipality.

The Town Hall designed by William Black and William Fagg and built by George F. Warren under the supervision of W. H. Coultas, the Clerk of Works, is a double-storey structure with the façade divided by an imposing clock tower.

Potchefstroom Carnegie Library (Wiki Commons)

Benoni Carnegie Hall

When Johann Rissik the Surveyor General of the ZAR was tasked with the onerous task of surveying the ‘uitval grond’ (odd pieces of land) between the occupied farms in this area, he in frustration named the district ‘Ben-oni’, Hebrew for son of my sorrow. Benoni became a municipality in 1907.

The Carnegie Foundation contributed $13 330 in 1914 towards this library. The building was designed and probably also constructed by the partnership of Reid & Knuckey. It seems David W. Reid managed the architectural side of the business while Wesley Knuckey was responsible for the construction aspects. The library was completed in 1923. It was situated where the Benoni Plaza is now.

According to the Artefacts website, Reid & Knuckey was established in 1906 with David Wilson Reid and Wesley Knuckey as directors. A branch was opened in Cape Town on the 31st January 1939 with the same directors, until Reid resigned in 1949.

Wesley Knuckey was recognized as a Rand Pioneer in 1891 and was President of the Rand Pioneer Association from 1929-30. He was also Chairman of the Cornish Association and President of the Master Builders Association around 1935/6.

In July 1974, the new Benoni Public Library opened on the corner of Elston Avenue and Tom Jones Street, as the old Carnegie Library was no longer able to meet the standards required of modern libraries.

Benoni Carnegie Library in Cranbourne Avenue. Subsequently demolished.

Newcastle Carnegie Library

Newcastle, in KZN was so named on 31 March 1854 in honour of Lord Newcastle, Colonial Secretary in 1852 and again in 1859.

A Carnegie grant of $7 290 in 1913 made the construction of this library possible. Designed by the architectural partnership of Chick & Bartholomew, the building was completed in 1915.

An undated specification by the architects on the proposed Carnegie Library to the Newcastle Town Council, now available on the Carnegie Columbia University Archive website, explained the design was in a classical style, eminently suited to public buildings. Windows were raised 6 feet above the floor to provide sufficient space for book shelves and newspaper stands. The entrance was flanked by Ionic columns to provide a dignified approach to the building. The entrance lead into the porch and then into a spacious vestibule that provided easy access to all parts of the building. In the circulating library room there was space for 4 000 volumes and the ‘closed’ system was adopted as opposed to the ‘open’ system that often resulted in the loss of books and the reading room could accommodate 44 readers.

Newcastle Mayor, Albert Dunton assured the Carnegie Foundation in a letter dated 14 March 1914, the best possible site had been allocated to the library. ‘When erected it will stand between the Magisterial offices and Court House on the one side and the Standard Bank of South Africa on the other, facing the Market Square’.

The Artefacts website states the partnership between H.E. Chick and B.V. Bartholomew in Durban continued from 1912 until 1939, after which the firm became Chick, Bartholomew & Poole.

Between 1925 and 1926 the above two partners, in consultation with the engineering firm of A. S. Joffe, provided an exciting example of industrial architecture at the C. G. Smith Sugar Store in Durban and introduced the use of the mushroom column and flat slab in South African architecture.

Until quite recently this library building, in the municipal gardens across the walkway from the municipal offices between Scott and Murchison Streets was used as an art gallery, but now regretfully it seems closed but still well maintained.

South elevation of the Newcastle Carnegie Library, designed by Chick & Bartolomew. Note National Monument Council plaque on the right (SJ de Klerk)

Germiston Carnegie Library

Germiston was laid out on the farm Elandsfontein in 1887, and it was only in 1904 that it was officially named Germiston, after a farm where John Jack, an early gold prospector and pioneer on the Rand was born, a few kilometres outside of Glasgow, Scotland.

The grant for the Germiston Carnegie Library was the largest amount made for any of the twelve libraries, totaling $26 470.

The building was designed by the Germiston Municipal Engineer, James Bright. According to Artefacts, James Bright was born in Ireland and served respectively as an assistant town engineer of Germiston, when he was at first named as an acting town engineer and later confirmed as a town engineer (1908–1932), a position from which he retired.

The recenly completed Dumisani Masilela Civic Theatre (SJ de Klerk)

Until recently the Carnegie Library went through a distressing period. At one time it served as a restaurant, then a club and by 2013 was derelict after a fire had largely destroyed what remained of the Library.

Nicholas Clarke provided a detailed description of the preservation and incorporation of the façade of the Carnegie Library into the recently constructed Dumisani Masilela Civic Theatre. Dumisani Masilela, the well-known actor in the TV series Rhythm City, was killed during an attempted hijacking in 2017. Interested readers are referred to Clarke’s 2015 article in The Heritage Portal (click here to read).

Façade of the Carnegie Library incorporated into the Dumisani Masilela Civic Theatre (SJ de Klerk)

Krugersdorp Carnegie Library

The Carnegie Foundation endowment of $15 840 in 1917 enabled the town council to erect a new library building, which had up to then been housed in the town hall. The Town Engineer’s department under Mr. Dobson designed the building, with the David Yanghau the builder.

According to the Krugersdorp edition of The Standard newspaper, probably dating towards the end of 1921, at the official opening of the library, Mr. H. C. Reeve, Chairman of the Library Advisory Committee, said the library movement was launched many years ago at a small meeting in Keet’s Buildings, with the moving spirit being Miss Helena Martin, then principal of the Secondary School, the forerunner of the High School.

The Carnegie Library building was sadly demolished some time during the 1970’s and a new library opened on the same site in 1976. In 1987 the new library could boast with 12 400 adult members and 9 700 child members, 134 068 books and 23 staff members serving the main library, three branch libraries and various depots at retirement homes and nursery schools.

Carnegie Library building, Krugersdorp. Note the date 1920 on the parapet. Demolished.

Conclusion

In 1917, with the USA’s entry into the Great War, grants for library buildings ceased, mainly because of the lack of material and labour. After the war earlier commitments were honoured, but because of a change of policy, no new endowments were made for the construction of public libraries.

A survey commissioned by the trustees of the Carnegie Foundation during 1915, found many of the libraries were not providing effective service because of the lack of trained librarians. Due to the above finding the trustees did not resume the programme directed towards the building of libraries after the Great War and instead focused on the training and education of librarians.

The Carnegie programme on the education and training of librarians falls beyond the ambit of this article but is also noteworthy for the far reaching and positive effects it had on the librarian profession.

Thank you to Mesdames Chista Nel and Miems Lamprecht for kindly providing information and photos of the Carnegie Libraries in Hopetown and Potchefstroom, respectively.

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Sources

- Anderson F. Carnegie Corporation. Library Program 1911 – 1961. Carnegie Corporation of New York. 1963.

- Benoni City Times. Benoni’s Centre of Learning. 29 August 2016.

- Clarke N. The Rebirth of the Germiston Carnegie Library in The Heritage Portal (www.theheritageportal.co.za). 2015

- Carnegie Corporation of New York Digital Archive in Columbia University Libraries Digital for correspondence on Vryheid, Standerton, Newcastle and Krugersdorp Carnegie Libraries.

- De Klerk W (Editor). Krugersdorp 100 Years. Perskor. 1987.

- Herbert G. Martienssen & the international style - The modern movement in South African architecture. A. A. Balkema. 1975.

- Greig D. A Guide to Architecture in South Africa. Howard Timmins. 1971.

- Johnstone C. Refurbishing the Muizenberg Carnegie Library and Post Office in The Heritage Portal (www.theheritageportal.co.za). 2016.

- Nienaber P. J. Suid-Afrikaanse Pleknaamwoordeboek. Deel 1. Tafelberg. 1972.

- Raper P. E., Möller L. A. & Du Plessis T. Dictionary of Southern African Place Names. Jonathan Ball. 2014.

- Richardson R. Historic Sites of South Africa. Struik. 2001.

- The Lowvelder 20 September 2019.

- Vryheid Centenary 1984. Printed by RABCO, Dundee. (Not dated)

- Walker M. A Statement in Stone. Shumani Printers. 2010.

- www.artefacts.co.za for information on architects and structures.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.