Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

My husband and I are avid photographers and have taken thousands of photographs. However, during a tidy up, we found a sheet of un-mounted colour slides lying in our garage. Examining the 28 images, we found them to be iconic of Johannesburg and the apartheid past. The photographs are full of social comment, especially notable in hindsight. They were likely to have been taken throughout the 1980s, judging from the existence of the trolley bus system (which ended in 1986) and the evidence of early minibus taxis (which started in 1987). We have no idea who the photographer could be.

One of the photographs from the collection also forms a tribute to an unknown municipal worker, circa 1985, Johannesburg. Who was he? Where is he now? Did he manage to save up for his own home?

Unknown municipal worker, circa 1985

Many of the images are so perfectly captured that they could be seen as deliberate scenes from a stage play, perhaps an Athol Fugard political play opposing the system of apartheid, or a Paul Slabolepszky drama. Slabolepszky is the “quintessentially South African dramatist and cartographer of the white male soul facing the abyss” (Paul Slabolepszy website).

A high-wire act - Joburg’s electric trolley bus system

Johannesburg grew quickly and by 1954 the City Council had decided that most of the electric trams would be replaced by electric trolley-buses over a period of seven years. The last tram ran on 18 March 1961 (Transport museum, 2018). The replacement electric trolley bus system ran for 25 years, from 1961 to 1986. The trolley buses drew electricity from overhead wires and ran on the normal roads, rather than running on rails like the trams. After 1986 the double-decker trolley buses were replaced by diesel buses and the rather complex electrical infrastructure of the trolley bus system was removed and little trace of it remains.

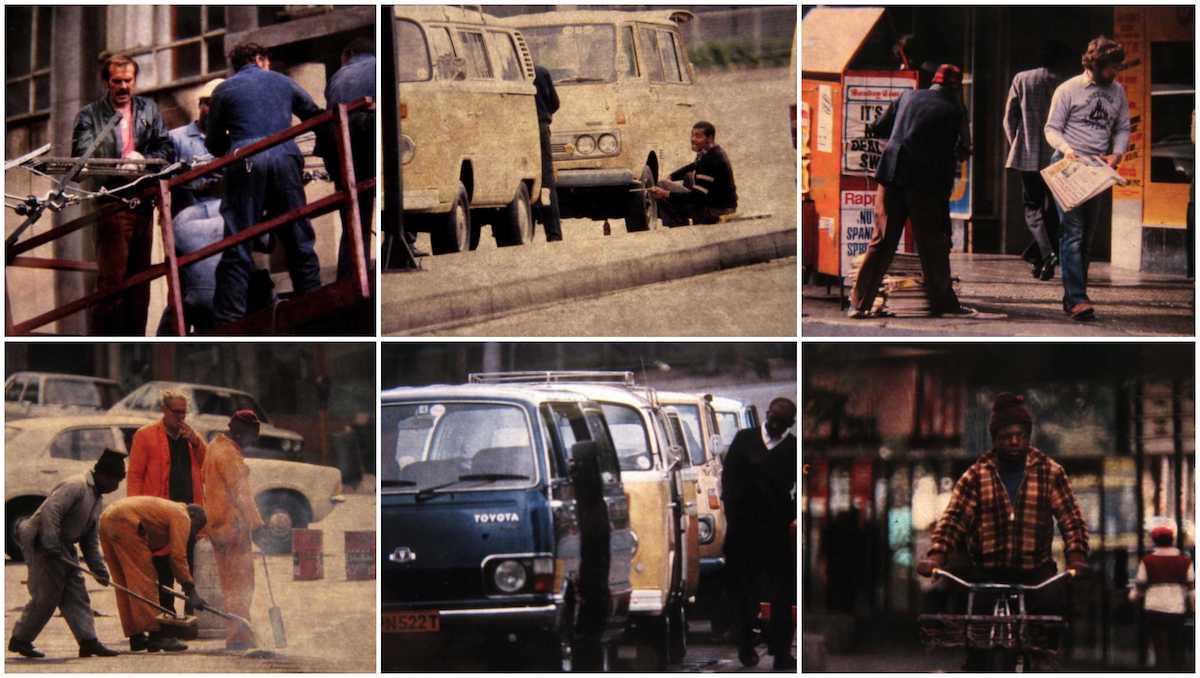

The photographs below highlight the challenge of keeping Johannesburg’s electric trolley buses running, with technicians having to service electrical wires two storeys above the street. They wear heavy leather gloves and the electrical system must have been ‘live’ when worked on. The photographs also reveal an interesting dynamic of race relations. These images must have been taken during the dark days of the 1980s, the time of various States of Emergency, bombings and disappearances, yet here both white men and black men must work as a team to do their jobs in difficult conditions. The ‘Athol Fugard’ script here would centre on the dangerous work on a high platform isolated from the rest of humanity, and how this situation fosters authentic and intense discussions between the men about their different struggles within the apartheid system.

The challenge of keeping Johannesburg’s electric trolley buses running

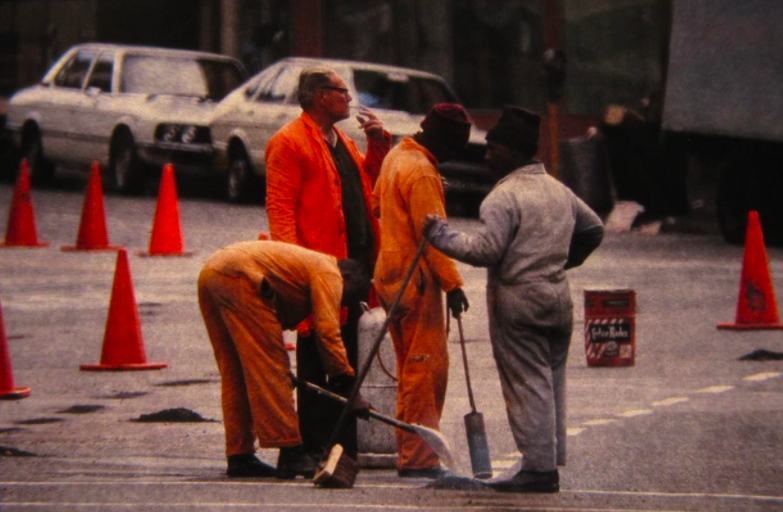

Road works and race relations

The following set of photographs also inadvertently illuminates race relations in a challenging racially-biased workplace situation, fixing roads. Potholes did not seem to be a thing in Johannesburg in the past, perhaps because of these guys and their blowtorches and smouldering pots of tar. We have also all heard about that archetypal white ‘baas’ supervising toiling black workers in the gruelling days under apartheid, here caught on camera. The ‘Athol Fugard’ script for this scenario would include the black workers’ seething resentment and whispered discussions as they sweat and slog. Frustratingly, the boss-man seems to stick close to his team, so they cannot have lengthy private discussions. In this way, they cannot formulate their plans to murder him and seal him under the road surface.

Spot the Duncan pavement parking meters in the bottom photograph. Johannesburg stopped using these in the 1980s and they are now considered ‘rare’ and are collectable as vintage. Those offered on Bidorbuy invariably say ‘Time Expired’.

Fixing roads in apartheid South Africa

Going the wrong way

One cannot be entirely sure what is happening in the next two photographs, other than almost everyone seems to be going the wrong way, possibly indicative of the political system at the time. It is unclear whether the guy in the beige uniform is a doorman for an unseen nearby hotel, or a traffic cop. If a cop, he seems a bit alone, unpopular (everyone moves away from him) and unsure of himself. He could be experiencing Paul Slabolepszky’s ‘white male angst’ at being an unwilling person in authority. These photographs resemble a stage setting designed to look like a busy street scene. It seems as if the people in the street are bit players who come on and off the stage, moving the story along.

In reality, this scene is presumably about that long roll of paper the ‘cop’ is holding, a plan of some kind that must relate to the bricks held down by string on the road. It is unclear where these two photographs were taken, other than they were in the Johannesburg CBD.

The guys in orange overalls are in the employ of the same municipal roads company as those with the blowtorch above. The prevalence of red traffic cones might imply that these photographs are all part of the same busy scenario of fixing the road.

A difficult scene to decipher

Revolution and fear on a street corner

Again, the location of this set of photographs is unknown, but likely to be the same part of downtown Johannesburg as the other photographs. There does seem to be a yellow truck in the window of one of the shops, which seems odd, perhaps a vehicle showroom. The ‘Athol Fugard’ scenario here would be the relationship between the older man in the red jacket and the young guy in the checked shirt with the bicycle. After he delivers the newspapers, the young guy is off on some dangerous mission, looking terrified. The older black man in the red jacket knows the young guy is in some bad trouble, something to do with the anti-apartheid ‘struggle’ and terrorism, and which is slowly revealed through the dialogue between the two men.

A red jacket and checked shirt

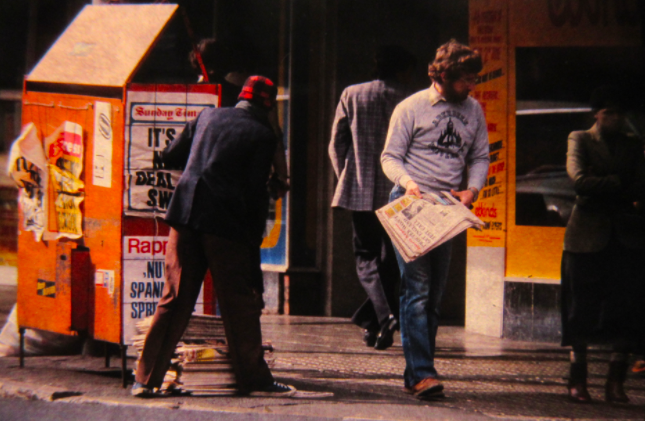

I make my own news from a street corner

In the two photographs below, it is the newspaper seller with the red tartan beanie who is the main ‘Athol Fugard’ character. The play shows how he makes his tedious days more interesting by observing and editorialising on the state of play in urban street society. He can’t read the various newspaper headlines, but as he is a shrewd observer, makes up his own news based on what he sees around him. It also looks like, no matter what crises are out there, the Springboks will always be in the headlines. The Sunday Times headline could be about some new deal with South West Africa (SWA).

The newspaper seller

The rise of the minibus taxi industry

In the 1960s, the South African economy had taken the decision to foreground private motor car ownership, thus kick-starting the local motor industry, to the detriment of most black people who could not afford a car. As more people began moving to South Africa’s cities, they found the existing public transport inadequate. Up to then, the South African government had a state-owned monopoly on both buses and trains, but with the increasing political violence of the 1980s and the burning of Putco buses, the government felt that it was no longer useful to operate in the public transport sector and began to deregulate the transport industry. In 1987 black taxi operators stepped in. The minibus taxi industry has become known for its violence and bad driving, yet does about 15 million commuter trips per day and generates about R90 billion in revenue annually. Taxi ranks developed informally, where most convenient for drivers and passengers, and perhaps less convenient for other motorists.

The two images below show the early use of Volkswagen Kombis and other types of passengers vans, all superseded by the now ubiquitous sixteen-seater Toyota minibus.

Taxis from the 1980s

About the author: Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Her current interests encompass cities and urban greening, material culture (what trash can tell us), degraded peripheries and researching the disintegration (and rehabilitation) of landscapes and buildings. She is currently a Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, QwaQwa, University of Free State (South Africa).

Sources

- Transport museum article (2018). Photographic Exhibition – the Story of Joburg Trams. Heritage Portal.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.