Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Long before man ever travelled up the pass, herds of eland, searching for greener pastures, crossed here in the winter months. Traditionally migratory elephants led by the herds matriarch, would make their way down to their grazing grounds on the Cape Flats. A Khoi tribe, known as Gantauwers (People of the Eland) also followed this pass. They called the path T’kanna Ouwe or Gantouw, ‘Gan’ being the Khoi word for eland and ‘touw’ the Khoi word for path. Later travellers also took up this meaning, calling it the Elandspat (path of the eland). Later still - ox wagon travellers called it the ‘Hottentots Holland Kloof.

It was early cattle buyers like Hendrik Lacus and Jeronimus Cruse, sent in 1663 by Zacharias Wagenaar - the replacement for Jan van Riebeeck as Commander at the Cape - who were possibly the first white people to brave the path over the kloof.

From Cape Town to the Pass

It is worth noting, although often overlooked, that the Gantouw Pass was not the only obstacle that had to be overcome in order to leave Cape Town and head east. The Cape Flats was a notorious place for the bogging down of wagons in thick sand. As a consequence there was no ‘one road’ across the Flats, as wagon drovers tried not to follow the tracks of a previous vehicle that had broken through the thin top stable layer of sand.

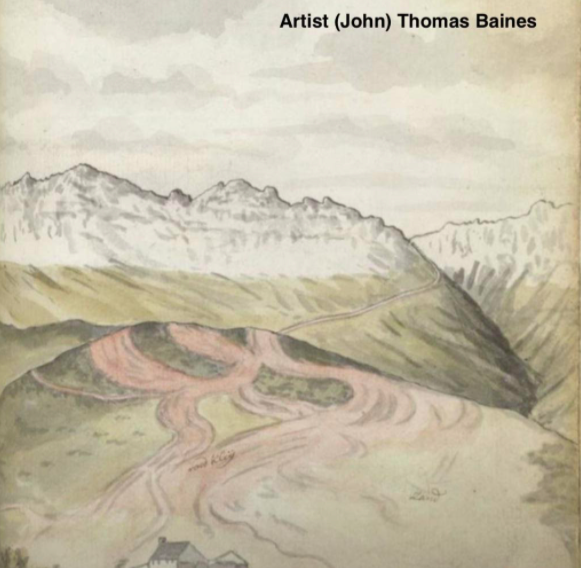

Even on the lower hills, passing the present Sir Lowry’s Pass village, waggons had to overcome the ‘Roode Hoogte’ or the ‘Red Heights’, another area of unstable ground through which the wagoneers tried to pick an independent way. This is well illustrated in the water colour below of the Hottentots Holland mountain pass, with its myriad of tracks in the foreground. The actual line of the pass beyond is also quite accurately depicted as it snakes its way up and round the mountainside. The article's main photo was taken from approximately the same position as the watercolour. It shows the Toll House as it is now with the grooves of the wagon trails still visible curving up the ‘Roode Hoogte’ hill behind the ‘Tolhuys’.

Watercolour of the Pass

Explorer, Author and Artist (John) Thomas Baines writes:

After an early breakfast, we mounted our horses, and almost immediately commenced the ascent which leads to the pass called Hottentot-Holland Kloof. At the first part of it, the road is not very steep, but as soon as the traveller enters the hollow way of the Roode Hoogte (the Red Heights) the difficulty of the ascent begins. This is a lower hill forming the foot of the mountain, and composed of a hard, barren, reddish, clayey, ferruginous earth, into which the road, towards its summit, is cut down to the depth of, perhaps, twenty feet. After this he has to climb the rocky mountain itself, and will not, without some surprise, behold loaded waggons ascending and descending so steep and frightful a road……The danger in which both oxen and waggon are placed while passing the mountains, renders the utmost care and vigilance indispensable. For should they become restive, and deviate from the proper road, or obstinately refuse to draw, the waggon would be thrown down the precipice, dragging them, and perhaps the driver also, along with it to inevitable destruction.

In 1808-97 ox wagons were recorded to have used the pass. Extra oxen being hired for the ascent from farms near the base of the pass such as Goedeverwaching (built in 1795) with each wagon using up to 24 oxen for the ascent. The nearby ‘Cloevermaaker’s Huys’ was used a Toll House, each loaded wagon being charged four shillings. These early travellers were extremely challenged by the steep and rocky ascent. Oxen were frequently killed and wagons smashed as they lost ground and fell back down the mountain. The route was so severe that more than a fifth of the wagons were damaged. Thus it became expedient at times to unload the wagons, take them up piece by piece, and reassemble them at the summit, while the oxen and travellers scrambled up over the rocks. Grooves in the rocks made by the brake drag-shoes which locked the wheels on the descent on the wagons can still be seen in the rock of the pass after 250 years.

Grooves in the rock (Steve Chadwick)

During the early 1800’s a small maintenance gang was employed to keep the pass in reasonable shape. If you look carefully you may see that stones have been shaped and let into the deeper old grooves of the pass. The capping maintenance stones themselves have then been worn down with their own grooves. Sad to say that off road bikers sometimes illegally go on the pass, and as they accelerate they often ‘kick’ out these maintenance capping stones.

In 1797 Lady Anne Barnard, who made the trip up the kloof declared, “The path to the top was very perpendicular and the jutting rocks over which the wagon was to be pulled were so large that we were astonished how it was accomplished at all. Particularly at one point called ‘The Porch’”.

Towards the end of the 18th century the pass was once used by a certain married man who ran away with a beautiful slave girl called Zara. His wife sued for divorce and that his name should be struck off any records.

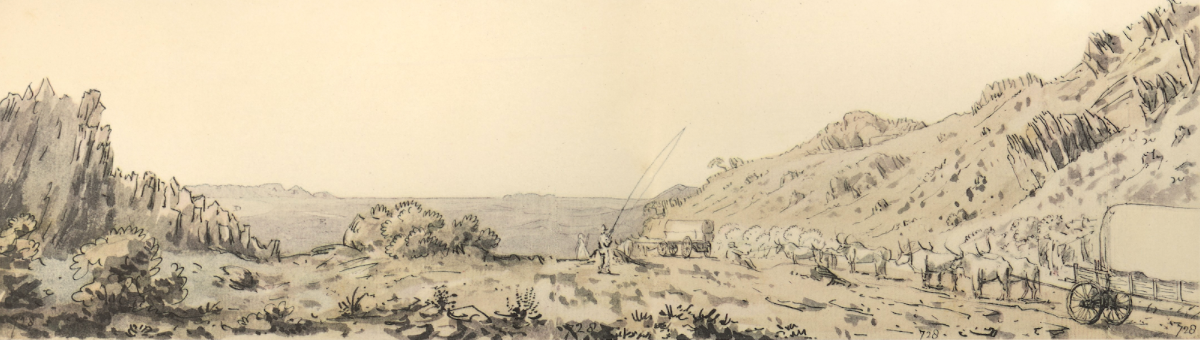

This drawing by William Burchell depicts wagon teams that have crested the top of the Hottentots Holland Kloof. The scene as they continue their trek east seems almost tranquil with relief, as they leave the struggle of the kloof ascent behind them.

The Gantouw Pass Cannons

A short path up from the crest take you to the signal cannons. In 1734 the VOC – Dutch East India Company introduced the ‘Dutch Call-Up Cannon signal system’, which eventually consisted of 54 strategically placed cannons. The system was designed to help Burgers form a communication link between the castle and the outlying districts, and was designed to be effective as far as Citrusdal in the North, Worcester to the North east, and Swellandam to the South East. Each cannon had a dedicated gunner who lived nearby and who was responsible for firing the next cannon in the chain.

A threat to cape Town activated the signal system and Burgers from far flung districts would hurry to its defence.

In answer to the cannons, in July 1795, one hundred and sixty-eight mounted men from Swellendam under the command of Jacobus Delport, answered the call and rode down through the kloof. The Dutch troops under Colonel Robert Jacob Gordon surrendered to the British on the 16th September. This was the first of two British take overs of the Cape Colony.

The signal system was used for the 5th and last time in January 1806, when the British landed at Blaauwberg. Thereafter the cannon signal system was abandoned.

It is understood that the Helderberg Renaissance Foundation is trying to restore the canons to firing condition, and also to conduct this event on National Heritage day 24th September each year.

The pass was declared a national monument in 1958.

Two views of the old Toll House, originally called ‘Cloevermaaker Huys’. The top photo was taken after the building was no longer in use as a ‘Toll House’, i.e. post the opening of the new 1830 pass. The building then fell into disrepair. In the bottom photo - taken from almost the same vantage point - we may still see similar trees and the same mountain skyline. In the late 1800’s the structure was rehabilitated and was in use as a dwelling until the late 1990s.

A stop before reaching the ‘Toll Huis’ may well have been at ‘Brinks Inn’, now known as Goedeverwachting. The original buildings of ‘The Inn’ stand near the road some 100m up from the current larger house, and are still used as dwellings.

In a more recent twist of history, politicians of that time needed a secluded base near Cape Town, where they might discuss issues regarding the imminent release of Nelson Mandela from prison on Robben island. The Old Toll House was chosen as an ideal secluded location where plans and decisions could be made, away from media attention. Nelson Mandela was released on February 11, 1990.

The building now has been allowed to fall back into ruin.

The New Pass

It was Lt-General Sir Gailbraith Lowry Cole, Governor of the Cape Colony from 1828 to 1833, who instigated improvements to this pass.

Lt-General Sir Gailbraith Lowry Cole (Wikipedia)

He requested that Major C. C. Mitchell inspect the Kloof pass with a view to making improvements. This done, Major Mitchell drew up a plan showing that a new road with easy gradients could be built south of the old kloof. The estimated cost being £7,000.

Work was authorised by Sir Lowry in 1829, without the Secretary of State’s permission, whereupon Sir Lowry was ticked off: “Build at your expense!” However, the UK government later relented and agreed to pay for the new pass.

The new road, which finally cost £7,011, was completed using convict labour and was opened on 6 July 1830. Initially there was a toll gate at the top of the pass.

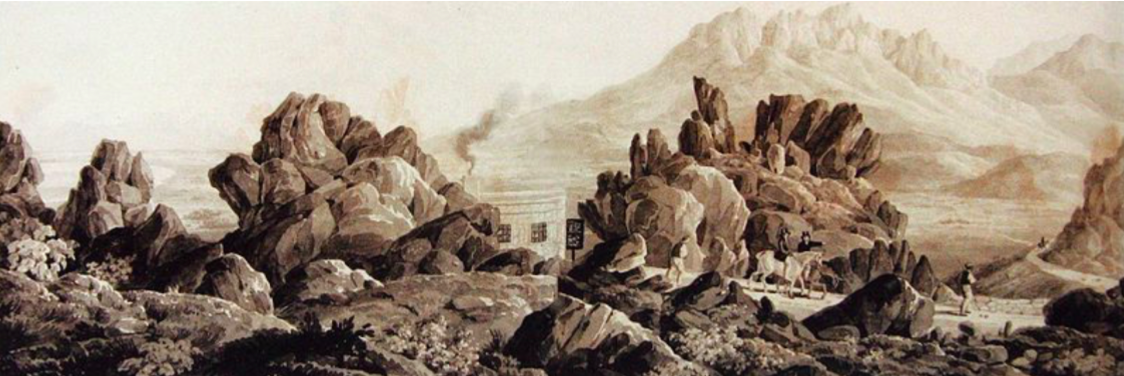

The original Toll Keepers house at the summit of Sir Lowry’s Pass. An 1832 pen and wash drawing by Charles D’Oyly. Note the accurate portrayal of the hills of West Peak and the Dome in the background.

The road remained narrow to the extent that vehicles could pass each other only at selected points on the route. In the 1930s, the pass was widened and tarred; it was further improved in 1956 when it was further widened.

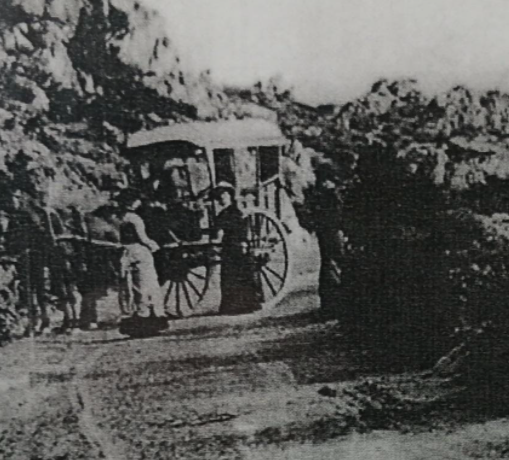

Photos of the new road in 1895.

In 1984 the upper parts were widened to four lanes through a reinforced concrete construction at a cost of R4.5 million.

Two historical uses of the new pass

November 1832: Lt Duthie was courting the daughter of George Rex (reported to be an illegitimate son of Prince George – afterward George III) in Knysna. Because he was enjoying his courtship and was very much in love he left his departure to the last minute. It took him five days to gallop madly through torrential rain, swim rivers, change horses, descend the pass and race through Somerset West at sundown, to reach the castle at 11 o’clock, with one hour to spare to the expiry of his leave.

December 1835: In retaliation for incessant cattle raids on the eastern frontier, on 11 December 1834 a Cape government commando killed a Xhosa chief of high rank, thus incensing the tribesmen. An army of 10,000 men, led by Maqoma, a brother of the slain chief, swept across the frontier into the Colony, pillaging and burning homesteads and killing all who resisted. Survivors sheltered in Grahamstown. Lt-Colonel Harry Smith was sent to relieve the settlers and made the 600 miles to Grahamstown on 6 January 1835, just six days after leaving Cape Town.

If you have any additional memories, photos or historical details please contact Steve Chadwick - slioch980@gmail.com

Compiled with grateful thanks from the following references:

- Peggy Heap – The story of Hottentots Holland.

- www.Nitidacannonstation.co.za

- Ryan Norris – SLP resident.

- Wikipedia.

- Mari Fouché - The story of Sir Lowry’s Pass

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.