I presented this story at the Valentine's Day Johannesburg Heritage Foundation celebration on the lawns of Northwards and thought Heritage Portal readers would also enjoy this South African story of love, endurance and resilience against the backdrop of the Second World War. It was one of seven presented at this event.

The Piano War, published by David Philip in 2003 and written by Graeme Friedman, is a remarkable work that sits at the intersection of biography, wartime history and love story. It belongs to a small but significant body of South African narratives that connect local lives to the vast upheavals of World War II and the Holocaust, while retaining an intimate human focus.

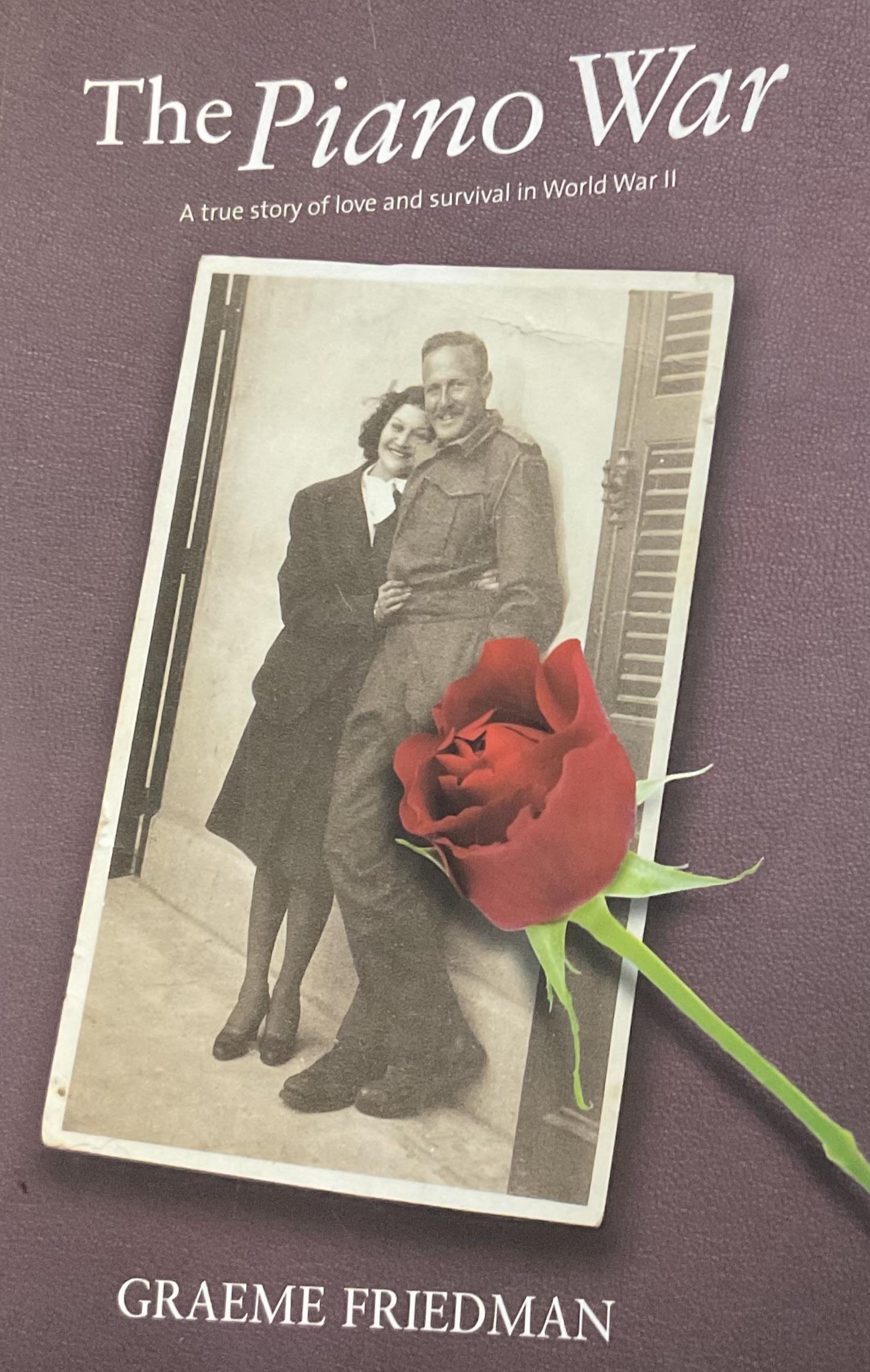

Book Cover

I first encountered the book while researching the life of Manfred Hermer, founder of the architectural practice that became GLH. That connection — through his brother Bennie Hermer — reveals how deeply embedded this story is within Johannesburg’s professional and cultural networks. Yet the narrative itself extends far beyond South Africa, into Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, giving it an unexpectedly international reach.

A story framed by the years 1938–1943. The core of The Piano War unfolds over roughly five years — from 1938, when the gifted Johannesburg pianist Olda Mehr, from Kensington, leaves for London on a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music, to early 1943, when she and Bennie Hermer are reunited and ultimately marry.

Olda travels to London with her mother, Ida Mehr, aboard the Union-Castle liner Dunnottar Castle, carrying with her both musical ambition and youthful hope. In London they rent modest accommodation and purchase a Brimsmead grand piano — an object that will later acquire profound symbolic meaning. The piano is financed on a hire purchase from a London firm of piano dealers, but it is a transaction that cannot be concluded through force of circumstance.

Dunnottar Castle World War II (Wikipedia)

In June 1939 Olda’s father, Joseph Mehr — a Johannesburg draper — joins them. Two months later the family makes a fateful decision to visit relatives in Poland. Germany invades days later, trapping them in Europe.

The family is separated. Joseph Mehr is detained and ultimately dies in an internment camp in Germany, a loss that casts a long emotional shadow over the narrative.

From this point the book develops two parallel storylines — one of its strongest narrative devices.

Olda and her mother endure detention, displacement, interrogation and precarious survival within Nazi-controlled Europe. At one stage they live in Berlin in conditions the author describes metaphorically as life in a “U-boat” — submerged, hidden, constantly under threat. In an extraordinary twist, Olda becomes an organist at a Catholic cathedral. The kindnesses that sustain mother and daughter during this period are frequently provided by Roman Catholics, offering a quiet counterpoint of compassion within a brutal regime.

Meanwhile Bennie Hermer is serving as a medical officer with South African forces in North Africa. Captured after the fall of Tobruk, he escapes captivity and survives with the assistance of Senussi tribesmen in the Libyan desert before reaching Allied forces and being flown to Cairo.

Late in 1942 Olda and Ida are included in a group of internees exchanged for Germans in Palestine. Their journey takes them via Vienna and Istanbul to Cairo.

There, in one of the most astonishing coincidences of wartime biography, Bennie and Olda encounter each other by chance on the streets.

The improbability of this reunion attracted international attention at the time, with Time Magazine reportedly describing the episode as “Love, Believe It or Not.”

They marry in Cairo soon afterwards. Returning to South Africa, they celebrate a second marriage ceremony at the Great Park Synagogue in Johannesburg — an unusual circumstance that results in the couple commemorating two wedding anniversaries throughout their lives.

The post-war chapters resist sentimentality. Bennie becomes a much-loved Johannesburg doctor, remembered for compassion as much as competence. The couple raise three children — Joan, Ken and Roy — and build a stable family life.

Olda’s trajectory is more complicated. Her musical career does not resume; the scholarship lapses. The psychological impact of her wartime experiences persists, manifesting in periods of melancholy and depression that today might be recognised as post-traumatic stress. The narrative acknowledges that survival does not erase trauma.

Yet the marriage endures — affectionate, resilient, deeply bonded by shared experience.

The book’s title derives from the Brimsmead grand piano purchased in London before the war. Reclaimed by the piano company and placed in storage after the family’s disappearance, it becomes the central metaphor of the story: interrupted promise, lost opportunity, memory suspended in time and dreams that cannot be fully recovered.

Even after the war the family still owes money on the instrument, yet transporting it to Johannesburg is impossible. The silent piano stands as a poignant symbol of lives interrupted by history.

What makes The Piano War particularly compelling is the convergence of several themes:

- the fragility of civilian life in wartime

- the endurance of love across separation

- acts of kindness across religious and cultural boundaries

- the role of chance and serendipity in survival

- and the long psychological aftermath of trauma

It is also a story of family connections — linking medicine, architecture, music and community within Johannesburg’s Jewish society.

The Piano War is ultimately a narrative of love triumphant — but not simplified. Loss remains. Trauma remains. Dreams change shape. Yet the relationship between Olda and Bennie survives war, imprisonment, separation and grief.

Like a Chopin nocturne — tender, wistful and enduring — the story reminds us that even when life’s grand piano falls silent, love can continue to resonate. I found the book a pleasure to read and it is a story that resonates.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also a previous Chairperson of HASA.