Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Ever since the Millennium the buzzword has been “Globalisation”, which paradoxically was given prominence by the anti-globalisation movement; those people who saw the threat of the multinational companies creating a new world order. By definition Globalisation is “the process enabling financial and investment markets to operate internationally, largely as a result of deregulation and improved communications” (Collins). The word came into everyday speech in the 1990’s having been coined first in the 1960’s by economists.

A moot question to be asked is when did Globalisation really get started?

Some would argue that Globalisation was initiated when Christopher Columbus in 1492 sailed the ocean blue and discovered the Americas, although he was seeking the Indies (the collective name for China, Japan and Indonesia). Knowing that the world was round he used the north-east trade winds to sail westwards, across the Atlantic Ocean. He and his fleet of three little ships set sail from the Canary Islands and after several unnerving weeks at sea a look-out at last sighted land, which happened to be an island (in a group we now know as the Bahamas). On landing he went down on his knees in thanks to God and claimed the island for Spain, naming it San Salvador (Holy Saviour). He truly believed he was in the Indies (hence the name West Indies today) and soon sailed on to seek China and its Emperor but found instead the island of Cuba and thence Hispaniola (Spanish Island). His ship, the “Santa Maria” was wrecked on a coral reef and he chose to return to Europe on the caravel “Nina” along with the third ship in the flotilla the “Pinta”. It was an arduous passage back to Spain in heavy seas via the Azores and Lisbon and on arrival at Palos de la Frontera he was summoned to the royal court in Barcelona and declared Admiral of the Ocean Sea. He would undertake three more voyages and he believed to his dying day that he was exploring the coast of China. Others would follow in his wake all intent on finding a passage to China but instead they found a “New World” - the Americas (so named after Amerigo Vespucci).

Whilst the Spanish were intent on going west to find the Indies their Iberian cousins - the Portuguese were intent on finding a passage to the Indies via the South Atlantic around the continent of Africa. Prince Henry the Navigator was the inspiration of the voyages down the west coast of Africa, which after his death, opened the sea route to the Orient.

There was a certain amount of religious zeal which accompanied the voyages of the Spanish and Portuguese. In 1492 the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella conquered Granada, the last stronghold of the Moors (Muslims) in Spain and this put into question future co-operation with the Islamic world of North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean. It was because of the wish to avoid the Muslim middle-men of the Middle East that sea routes had to be found.

There was of course a land route to China used by merchants – the famed Silk Road which had been used for centuries and was known to the Greeks and Romans. The Venetian Marco Polo travelled it in the 1271 to become an envoy of Kublai Khan, only returning to Venice in 1295. In 1298 he was a prisoner of the Genoese and whilst incarcerated dictated an account of his travels to Rustichello, which became known as “Il Milione” (Book of Marvels). It was to be the first travel guide and it gave a mouth watering depiction of the advanced civilisation to be found in the Orient.

The Portuguese mariner Bartolomeu Dias, was the first since the Phoenicians to sail around the southern tip of Africa in the year 1488, however he only reached as far as the Keiskamma River (near present day Hamburg, Eastern Cape) before his crew implored him to turn back, but his voyage was to be the prelude to Vasco da Gama’s epic voyage to Calicut on the west coast of India, some ten years later. Maritime trade between Europe, India and the Indies thus became possible, which would in time create a rivalry between the fleets of the Portuguese, Spanish, French, Dutch and English.

Although the Portuguese had the early monopoly it was soon assailed by the others, notably the Dutch who in 1602 created a cartel to be known as the “Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie” or the VOC (in English the United East India Company), which would be the first joint stock company in history and its trade with India, China, Japan and Java would require a considerable number of ships, both merchant and warships as well as administrative centres in the Netherlands and Batavia (now Jakarta) in Java. Thus the VOC became a vast undertaking, if you like the first multinational, with its tentacles reaching across the globe. The company monogram (logo) consisted of the company’s three initials with a large “V” in the middle with a small “O” on the left antennae and a small “C” on the right.

VOC logo

I would rather like to think that the rounding of the Cape of Good Hope (first known as the “Cabo Tormentoso” - Cape of Storms) was the precursor to Globalisation which first took place in the seventeenth century and to prove the point I refer to the book entitled “Vermeer’s Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World” (2008) by Timothy Brook the Canadian historian who is an expert in Sinology (the study of China). In the book he explores the beginnings of world trade between America, Europe and the Orient by deftly using paintings mainly by Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) to act as windows to look back into the 17th century, to reveal its world of trade and cultural exchange.

The particular paintings (excepting the “View of Delft”) at first glance merely depict domestic scenes but on further study they reveal much more when one takes a closer look at the accoutrements that are placed in a room. These trappings had come from all over the world and thus proved that a thriving world trade was being carried out during the 17th century with the Dutch being market leaders. The Dutch Golden Age would start to wane towards the end of the 18th century and the VOC itself was dissolved on the last day of 1799.

The paintings used by Brook in “Vermeer’s Hat”, are as follows and unless otherwise stated are by Johannes Vermeer:

- “View of Delft” (Mauritshuis, Den Haag).

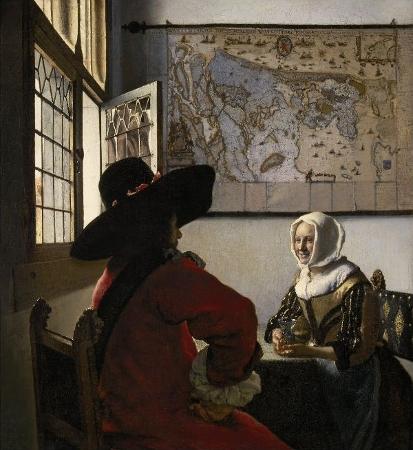

- “Officer and Laughing Girl” (Frick Collection, New York).

- “Young Woman Reading a Letter at an Open Window” (Gemaldegalerie, Dresden).

- “The Geographer” (Stadelsches Kunsinstitut, Frankfurt-am-Main).

- “Woman Holding a Balance” (Widener Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.).

- “The Card Player” by Hendrik Van der Burch (Detroit Institute of Arts)

- “The Journey of the Three Magi to Bethlehem” by Leonaert Bramer (Collection of the New York Historical Society.

Officer and Laughing Girl by Johannes Vermeer

“Vermeer’s Hat” is a delight of a book and it takes the reader back in time to when gold, silver, furs, tobacco, porcelain and spices were being traded between the Americas, Europe and the Orient; indeed the first World Wide Web.

References and further reading:

- “What is globalisation” by Simon Jeffrey – The Guardian 31.10.2002.

- “Journeys of the Great Explorers” AA publication 1992.

- “Alistair Cooke’s America” by Alistair Cooke 1973.

- “Dias 88” a booklet celebrating the 500th anniversary of Dias’ passage around the Cape (1988).

- “Vermeer’s Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World” by Timothy Brook (2008).

- “Complete Interactive Vermeer Catalogue” www.essentialvermeer.com

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.