Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

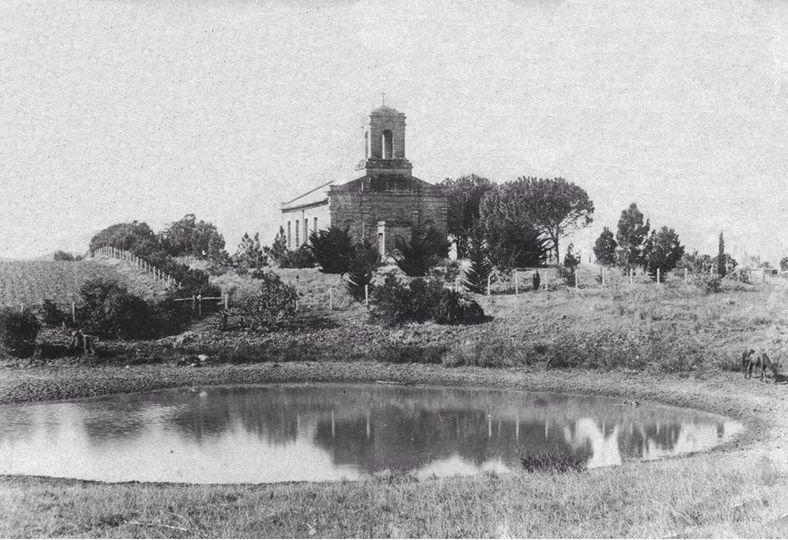

On my visits to Cape Town, I often find myself drawn to this attractive little stone church and attendant graveyard situated on the little knoll above Main Street, Rondebosch. It is hard to explain my interest. It is not because of devoutness, since I am not very religious. It may well be due to the association of this church with two of the Cape Colony’s important official appointments: the first Surveyor General and the first Anglican Bishop of Cape Town. But perhaps one requires no real reason, other than curiosity to visit this very interesting and historical site.

Rondebosch, originated from the Dutch name ‘rondeboschen’ meaning round thicket, referring to a clump of trees that grew on the banks of the Liesbeek River.

By the 1830s the village of Rondebosch had become an important residential area for merchants, government officials and visitors from India, yet it lacked a place of worship.

Major Charles Michell (1793-1851), a talented and many faceted man - soldier, musician, artist, surveyor, civil engineer and architect, appointed as the Cape Colony’s first Surveyor General in 1828, decided to remedy this omission. At a meeting held in early August 1832, Michell along with four other Anglicans were elected to serve as trustees of the proposed church building. Following a petition to the Governor for a piece of government land between the Groote Schuur estate of Abraham de Smidt and the Main Road, approval was speedily granted barely three weeks later. Six days later it was consecrated by the Bishop of Calcutta who happened to be visiting the Cape en route to India.

Initially, no drawing was known to exist of Michell’s church until the discovery in 1962, of a watercolour by the visiting Anglo-Indian civil servant Christopher Webb Smith in the Balfour Library of Cambridge University. Subsequently Michell’s architectural sketch surfaced amongst his daughter’s watercolour albums. It shows a rather plain whitewashed oblong building, covered by a thatched roof topped with a wooden bell-turret, surmounted with a cross.

Michell’s sketch of St Paul’s Church (Gordon Richings)

The stone for this building was obtained free from the neighbouring estate of De Smidt and funds were raised, amongst others, by appealing for public donations.

On 16 February 1834 the church was opened. Governor D’Urban and his wife as well as many other Cape Town citizens attended the ceremony. The little church was well received with one distinguished visitor describing it as ‘very light, very plain, without either gallery or ceiling, but airy and commodious ….’.

At about the same time Michell was designing another Anglican church in the frontier village of Bathurst. This lovely little church designed in the Neo-Classical style still stands proudly there. Michell was also consulted on the design or renovations to three other prominent churches in Cape Town: the Lutheran Church in Strand Street, St George’s Anglican Church and the Dutch Reformed Groote Kerk.

St John's, Bathurst

Notwithstanding Michell’s efforts, the Anglican community lagged the other Christian denominations in erecting churches for their own use. By 1848 only ten Anglican Churches existed in the whole of the Cape Colony. However, this dismal state was to change drastically with the arrival of the energetic Robert Gray (1809 – 1872), first Anglican Bishop of Cape Town.

Stepping ashore in Table Bay in February 1848, Gray accompanied by his wife Sophia (1814 – 1871) established in excess of fifty Anglican Churches during the following two and a half decades.

Bishop Gray held strong views on church architecture. He disapproved of brick as building material for churches, preferring stone and favouring the Gothic Revival style, which in his view fittingly expressed the divine function of a church.

His opinion of church architecture reflected the view of the prevailing ecclesiological movement. Its proponents believed a Gothic style was the only type suited to a parish church and favoured a particular era of Gothic architecture, the ‘Decorated’. Churches built in the Neo-Classical style were regarded by Ecclesiologists as replicas of pagan temples of Hellenic Greece and Imperial Rome and therefore unfit for Christian worship.

Robert and Sophia Gray would have preferred their churches to be built in the Decorated style, but for reasons of economy, most of their churches were built in the Early English style, the simplest of the Gothic Revival types.

The Decorated form of the Gothic, differed from the Early English in that the windows were larger, divided into two or more vertical panels and adorned with ornamentation.

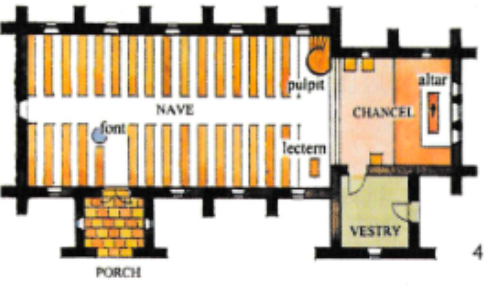

Soon after arriving in Cape Town, Bishop Gray met the parishioners of St Paul’s to discuss extensions to this church. Among assorted plans submitted, was a plan of a church in the Decorated style provided by the Bishop. It involved adding a large nave and aisles onto the existing Michell church, which was to serve as chancel upon completion of the nave. This proposal was accepted, and the foundation stone was laid on 20 February 1849 by then Governor Sir Harry Smith (1787 – 1860).

Plan of typical Gothic Revival Church (Desmond Morris)

Sophia as a young girl had proved herself a gifted draughtsman and artist. After her marriage to Robert Gray, Sophia kept up her interest in drawing. Later, when she knew that they would most likely be sent out to the Cape, she sketched and studied many of the churches in and around Durham, renowned for its old buildings. Aware that as the ‘Lady Bishop’ she might well be called upon to design and erect churches in a new country, she made a thorough study of the subject. When the Grays were about to leave England for the Cape, they advertised for books on architecture together with plans and drawings of churches, schools and houses. At that time there was no copyright system and buildings could be erected from existing plans. The Grays also liaised directly with William Butterfield, one of England’s foremost Victorian Gothic architects and it is therefore possible that Sophia merely copied and modified acquired plans. Desmond Martin argues that the high expectations Bishop Gray had of building fine Gothic churches had to be curbed because of the lack of skilled craftsmen and scarcity of suitable stone for the more elaborate ornamentation of Decorated and Norman churches. Hence, Sophia had to consider all these factors when revising the available architectural church plans, because generally only coarse stone was available. This resulted in the churches requiring thicker walls and featuring cruder detailing. Where finer windows and arches could be afforded, these were produced in England and shipped to South Africa.

It appears that only eleven architectural drawings of Sophia Gray have survived, and it is therefore rather problematic to assess her architectural contribution to church architecture at the Cape. Desmond Morris contends Sophia provided plans for probably 40 of the Anglican churches and chapels erected in the Cape Diocese.

Only six of the churches and chapels for which Sophia provided the plans were intended to become Decorated churches. They were St Paul’s in Rondebosch, another St Paul’s at Eerste River now Faure, St George’s at Knysna, St Saviour in Claremont, St Peter’s in Pietermaritzburg and St Mary’s in Woodstock.

Lych gate entrance from Main Street (SJ de Klerk)

By 1884 St Paul’s had achieved its present appearance, with a Lady Chapel and a new chancel added to an extended basilica-shaped nave and the bell-turret rising from the front wall.

The later additions were completed by London architect W. White (1825 – 1900). White was noted for his part in 19th century Gothic Revival architecture and church restorations. In style he was like that of William Butterfield.

The porch on the side of the Main Road is from an earlier date, but the lych gate was apparently added later, as is the porch on the town side.

Six stained glass windows in the church commemorate the wife of Cape Governor, Sir Phillip Wodehouse and her marble tombstone rests in the adjacent graveyard.

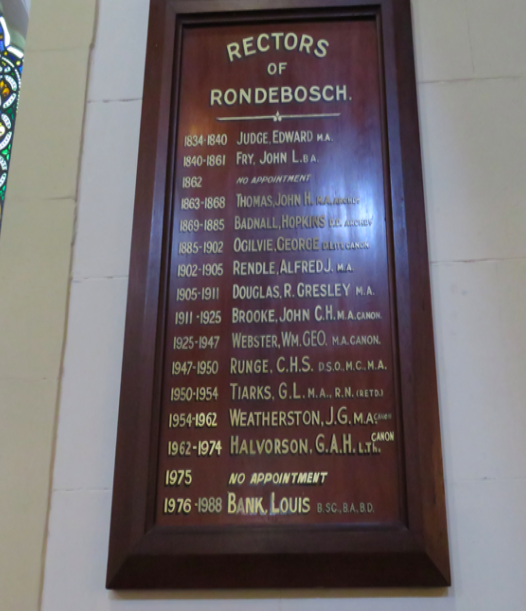

Past Rectors of St Paul’s (SJ de Klerk)

A graceful Cross of Sacrifice dedicated to those of this parish who gave their lives during the Great War adorns the area between the church and Main Street, below.

Cross of Sacrifice overlooking Main Road, commemorating parish members who fell in the Great War 1914 – 1918 (SJ de Klerk)

The inscription on the Cross of Sacrifice erected in 1921 reads: ‘To the glory of God and in ever grateful memory of those from this parish who fell in the Great War’. I don’t recall noting the name of the architect of this attractive monument and it would be interesting to know who designed it. One wonders if it might have been Gordon Leith, who returned to South Africa in 1921, after being retained by the Imperial War Graves Commission to design cemeteries and monuments to deceased soldiers in France, or perhaps Franklin Kendall who, amongst others, designed the war memorial tower at Grahamstown University and who was later entrusted with restoring the Groot Constantia manor house, following the disastrous fire of 1925.

The church graveyard situated immediately north of the church contains several unusual and historical tombstones. Hans Fransen states UCT architectural students conducted a full survey of the tombstones in 1999, which should make for interesting reading.

The tombstone that first caught my attention some years ago, is that of Captain A. C. Campbell, late 1st Bengal Cavalry, who died in 1845, aged 36 years. His tombstone mirrors the style of tombstone often seen in old European cemeteries in India and indeed the tablet containing the epitaph was sculpted by Holmes & Co. of Calcutta. The epitaph reads: ‘Sacred to the memory of Capt. A. C. Campbell. 1st Bengal Cavalry. Died 25 Oct. 1845 Aged 36 years. “Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord”.’

Weather worn tombstone of Captain A. C. Campbell, late 1st Bengal Cavalry. Note the plaque sculpted by Holmes & Co. in Calcutta (SJ de Klerk)

Langham-Carter, late Archivist of the Church of the Province of South Africa, quotes notes by C. Graham Botha, dating from 1907 that this tombstone originally appeared in the old Somerset Road cemetery. It must have been moved here when notices were placed in the press, urging families to remove the remains and monuments from the Somerset Road cemetery and inter them elsewhere, due to the intended levelling of the graves and construction on the vacated cemetery grounds from 1922, onwards.

The decay of this unusual tombstone moved me to contact the British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia (BACSA), requesting their assistance in restoring it. Regretfully, they declined as their primary purpose remains the preservation and restoration of British graves in the Indian subcontinent. Interestingly, BACSA advised the Bengal Cavalry Regiment was disbanded following the Indian Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 - 58.

Many officers of the East India Company spent their leave in South Africa due to the rather absurd furlough regulation, which determined that all leave at, or eastward of the Cape Colony, counted as service with full Indian pay and retention of Indian appointment, while westward both appointment and allowances were lost.

Rawlins writes - ‘many flocked to the Cape, and spent a pleasant furlough there, as the Dutch people are famed for their hospitality and sport and their daughters are exceedingly agreeable and good-looking …. Few young men could resist the charms of the fair maids of Cape Town; consequently, many a Cape girl married an Indian officer, or civilian better still, as the latter was always worth, dead or alive £300 a year! And these alliances afforded them much pleasure, as their parents were ambitious and rejoiced to see their girls lifted in the social scale and thus happily united.’

The second historic tombstone, although I did not initially realise its significance, is the beautiful marble sarcophagus of Catherine Wodehouse (1817 – 1866), wife of Cape Governor, Sir Phillip Wodehouse (1811 – 1887).

Tombstone of Catherine Wodehouse (SJ de Klerk)

Langham-Carter describes this tombstone as follows: ‘The large horizontal coped sarcophagus has sloping sides. Its height is about 0.6 of a metre and its length at the base about 2.2 meters. It lies west and east and near the west end are two projecting wings. No doubt the shape was meant to represent the Christian cross and one is also reminded of a cruciform church with a steeply pitched roof, a short chancel at the west end, north and south transepts and a long nave further east. The carved cinquefoils at the top of the four gables resemble the tracery at the head of a church window.

On the west wall a cinquefoil with three grapes pendant from each of its cusps contain the words: “Europe AD 1817 – 1832”. There are similar cinquefoils on the other gables. On the south we read “Asia AD 1833 – 1849”, on the east “America AD 1851 – 1861” and on the north “Africa AD 1862 – 1866”.

Along inscription runs the whole length of the south side under the slope of the coping “SACRED TO THE BELOVED MEMORY OF CATHERINE MARY WODEHOUSE THE DAUGHTER OF FRANCIS JOHN TEMPLER ESQUIRE AND WIFE OF SIR PHILLIP EDMOND WODEHOUSE”. This continues on the north side “WITH WHOM SHE WENT WHERESOEVER HE WENT IN THE FOUR QUARTERS OF THE WORLD AND TO WHOM HER DEATH IS THE IRREPAIRABLE LOSS OF HIS BEST COMPANION AND HIS MOST TRUSTED FRIEND. BORN JAN 2nd AD 1817 MARRIED DECEMBER 19th AD 1833 DIED OCTOBER 6th, 1866”.’

Langham-Carter goes on to explain that the tombstone is fashioned from white marble, probably from Carrara in Italy, reputedly the best in the world, and since the work is much too elaborate a work for local stonemasons of that period, it almost certainly came from England.

Stained glass windows of Saints Catherine and Mary, names Lady Wodehouse had borne (SJ de Klerk)

Two stained glass windows had been erected in the north aisle of the church not long before Sir Phillip Wodehouse arrived at the Cape in 1862. He may have admired them and probably arranged with the parish vestry to order six more from the same firm, for which he paid £100. Three were in place by May 1868. Langham-Carter states these were in place by 1858, which seems a misprint as Wodehouse had not yet arrived in the Cape by this date. The six can still be seen in the South aisle. Saints Catherine and Mary (whose names Lady Wodehouse had borne) are flanked by Saints Paul, Peter, Luke and John. Below them a single brass plaque simply states ‘CMW’.

It must have been a very difficult period for Sir Phillip Wodehouse who had to deal with reckless government spending, a depleted treasury and agitation to separate the eastern districts from the western ones.

While his wife was terminally ill from ‘a prolonged and painful disease’, possibly cancer, he faced the potential collapse of Basutoland, then involved in an exhausting and prolonged war with the Orange Free State. After placing Basutoland in 1868 under the direct authority of the High Commissioner for the Cape, Wodehouse departed the Cape for England in 1870. In 1872 he was appointed Governor of Bombay, finally retiring in 1877. Sir Phillip Wodehouse is buried in Kensal Green cemetery, London’s first garden cemetery, now considered the doyen of the Magnificent Seven London Cemeteries.

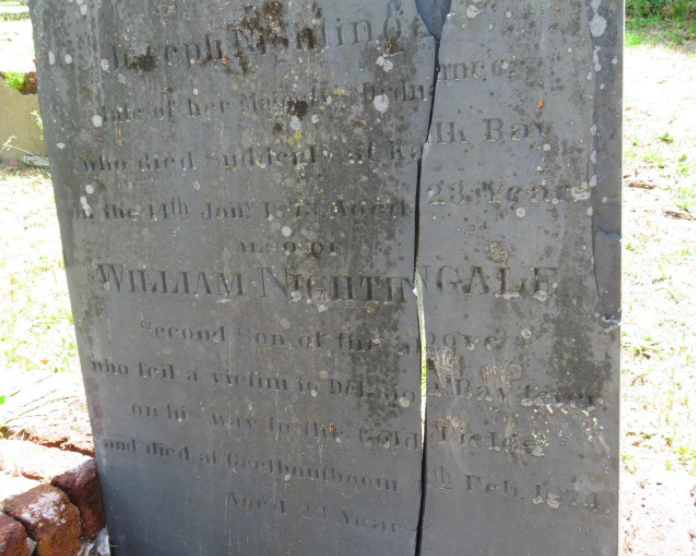

Another tombstone recollects the days when rumours of promising gold discoveries in the hinterland were trickling back to Cape Town.

Tombstone of brothers Joseph and William Nightingale (SJ de Klerk)

The now weathered slate tombstone commemorates the early deaths of the two Nightingale brothers. Joseph of Her Majesty’s Ordnance who died suddenly at Kalk Bay on 14 January 1873 in his 23rd year and William who fell a victim of Delagoa Bay fever on his way to the Gold Fields and died at Geelhoutboom during February 1874 in his 24th year.

Geelhoutboom, now an almost forgotten name, was the farm adjacent to the farm Graskop. where the town of the same name was later developed.

The churchyard contains several very interesting graves and both it and the little church are worth visiting.

Postscript: The approximately 40 churches and chapels for which Sophia Gray provided the plans are scattered throughout the smaller towns and villages situated in the Western Cape, Eastern Cape and Northern Cape Provinces and when touring these areas, visiting them is highly recommended.

Main image: St Paul’s Church viewed from the south (SJ de Klerk)

About the author: SJ De Klerk held many senior positions in HR during a distinguished career in the private sector. Since retiring he has dedicated time and resources to researching, exploring and writing about South African history.

Bibliography

- Fransen H. (2004). The Old Buildings of the Cape. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg.

- Greig, D. (1971). A Guide to the Architecture in South Africa. Howard Timmins, Cape Town.

- Gutsche T. (1970). The Bishop’s Lady. Howard Timmins, Cape Town.

- Haarhoff G. (2018). Forgotten Tracks and Trails of the Escarpment and Lowveld. Shanghai Kangshi Printing, Shanghai.

- Langham-Carter R. R. (1991). Catherine Wodehouse: in fond memory in Africana Notes and News, September 1991 Vol. 29 No. 7. Africana Society, Africana Museum, City of Johannesburg.

- Langham-Carter R. R. (1968). The Lost Inscriptions of Somerset Road in Africana Notes and News, September 1968 Vol. 18 No. 3. Africana Society, Africana Museum, City of Johannesburg.

- Lewcock R. (1963). Early Nineteenth Century Architecture in South Africa. A Study of the Interaction of two Cultures 1795 – 1837. A. A. Balkema, Cape Town.

- Martin D. (2005). The Bishop’s Churches. The Churches of Anglican Bishop Robert Gray. Struik Publishers, Cape Town.

- Picton-Seymour D. (1977). Victorian Buildings in South Africa. A. A. Balkema, Cape Town.

- Richings G. (2006). The Life and Times of Charles Michell. Fernwood Press, Simonstown.

- Wilkinson T. (1976). Two Monsoons. Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd. London.

- De Kock W. J. Editor (1976). Robert Gray in Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek Deel I by J. A. I. Agar-Hamilton. Tafelberg-Uitgewers, Kaapastad.

- Beyers C. J. Editor (1981). Sophia Gray in Suid-Afrikaanse Biografiese Woordeboek, Deel IV by R. R. Langham-Carter. Butterworth. Durban.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.