Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, well known Joburg explorer and writer, Lucille Davie, reveals the layered history of a special site south of Johannesburg. The piece was first published on the City of Johannesburg's website on 2 February 2011. Click here to view more of Davie's work.

A short drive south of the city, some 10 kilometres outside the CBD, are remnants of Joburg's first settlement of Khoisan, South Africa's oldest people.

They are to be found at the Eikenhof Khoisan Farm, portion 80, consisting of 247 hectares of land immediately south of the Klipriviersberg mountain, on the banks of the Klip River. The site has been occupied by Khoisan people for about 100 years, squeezed between several farms belonging to whites, who moved into the area from the 1850s onwards.

The Khoisan community appears to have settled on the site in the mid-1890s. A cluster of houses was established in the veld around a church, which doubled as a school. In those days it was known as Jackson's Drift, a reference to a crossing point about a kilometre downstream.

Over thousands of years the original peoples of South Africa – the San or Bushmen, and the Khoi – have lived side by side, and are now commonly called the Khoisan.

There are other interesting elements to the site: Stone Age artefacts, early traces of gold mining exploration, the battleground for control of Joburg in 1900, and a wetland.

Today the site consists of four buildings: the Ebenezer Congregational Church (see main image); two dilapidated, unoccupied houses; and a new house, positioned around a patch of mown grass some 30 metres north of the Klip River. The grass is scattered with rocks and syringa trees and beds of cannas and bright orange marigolds. Traces of other structures can be seen in the surrounding tall grass, mostly made of stone and clay; some are believed to be cattle kraals, others houses.

On a line flutters the washing of Hester Williams, the caretaker of the church. She lives with her husband in the newly built house, constructed in October last year by the church. She has been on the site for the past 30 years, and still draws her water from a well alongside her house, but has no electricity.

Hester Williams, the caretaker of the church, outside her new house (Lucille Davie)

Walking westwards along a raised rocky bank, there are four tunnels running into the bank, remnants of unsuccessful gold diggings. The site runs up the hill, to the top of the koppie. At the base of the koppie is a Rand Water plant, and further north is the Afrisam quarry.

Adam Mathysen standing alongside one of the four disused mine tunnels along the banks of the Klip River (Lucille Davie)

South of the river is a large wetland, running east and over the R554 freeway. Just beyond the freeway is Jackson's Drift, now a bridge. In the immediate vicinity of the bridge are abandoned buildings, remnants of what used to be the small village of Eikenhof. The ruins of a school, a post office and a hotel are discernible.

It was at Jackson's Drift and other places along the Klip River that British forces crossed in their successful assault upon Johannesburg in 1900 during the South African War of 1899-1902.

From the site the faint hum of the traffic on the R554 is audible. The farm runs over the freeway – a housing development now fills the eastern boundary, where a graveyard once stood. About 122 graves were moved to Sharpeville to make way for the development.

Besides the mild traffic din, the open space exudes the tranquillity of the countryside, with birds twittering and a breeze rustling through the tall grass.

Heritage report

A study of the farm was done in 2006 by PD Birkholtz of Archaeology Africa, on behalf of Khare Incorporated and various developers, whose proposals for portions of the site range from an entertainment complex, a shopping centre and petrol garage, to a mixed industrial and residential development (click here to view report).

"The heritage inventory has revealed the existence of at least 12 heritage sites located within the study area, of which the Ebenhezer Congregational Church site is certainly most significant," states Birkholtz's report.

"This church has immense symbolic significance for the erstwhile residents of the property. Its significance is augmented by the church building's relatively unique architectural characteristics as well as its possible age that is in excess of 100 years."

It appears that there was always a larger population of Khoisan or coloured people in the area, than white settlers. In 1921, it was estimated that there were three times the number of coloureds to whites.

Birkholtz states that in a letter by Inspector BJE Badenhorst, dated 1 November 1949 and addressed to the district commandant of the South African Police, there were "from 600 to 700 natives, Coloured, and Hottentot families on the farms around Eikenhof adjoining the Municipal area of Johannesburg" and that "some farmers have large Coloured and Hottentot families on their farms and the Native Laws are not applicable to them".

He indicates that families with names such as Damakwa, Le Batie and Goliath used to live at Eikenhof.

Fruit trees were planted. "The sawn-off stump of one of three large apricot trees which used to stand inside this yard was also found. Every year over the Festive Season, the reverend Mr Vernon de Jager would decorate one of these trees as a Christmas tree."

Established in 1904

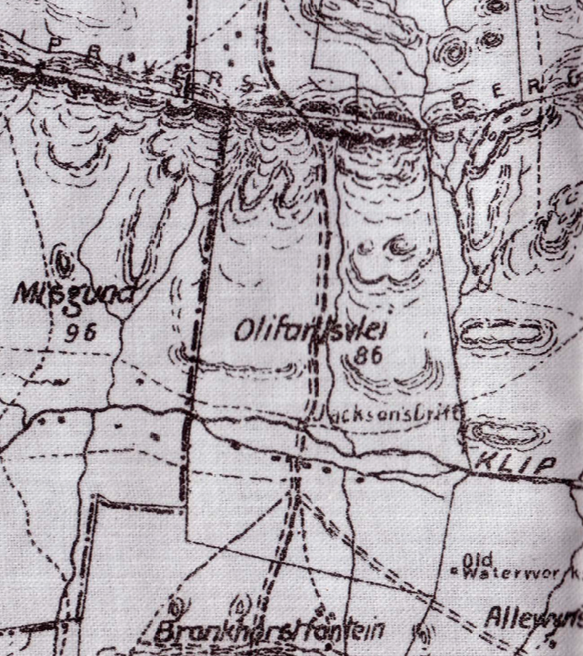

Birkholtz reveals that the farm Eikenhof was established in 1904 from two neighbouring farms: the eastern section of Misgund and the western section of Olifantsvlei. A mine, Vesta Mine, operated in the area, covering Eikenhof farm. When it was established in 1911 that mining operations were not profitable, the mine closed down.

Old map of the farms (included in 2006 HIA)

In the early 1960s, the community was removed to Eldorado Park in Soweto.

Adam Mathysen, the project co-ordinator of the Jackson's Drift Khoisan Development Association, has made an application to the Johannesburg Property Company (JPC) – the City owns the site – to enable the displaced community to possibly formally re-occupy the land.

The JPC confirms that they have received the application. A valuation of the site has been done by JPC, and the next phase of the process, going before the Transactions Committee, is possibly going to happen in March.

"We welcome initiatives that not only meet our social needs but enhance our historical and heritage sites," says JPC's media officer, Brian Mahlangu. "This project is one of them, and we are, as said earlier, working on it to ensure we achieve maximum benefit for our residents and stakeholders."

Mathysen was born in Eikenhof and attended school at the church. He moved with his family in the 1960s to Eldorado Park. He would like to see the repatriation of the graves that were moved to Sharpeville, and would also like to see it re-established as a farm, run as a co-operative.

His aunt, 89-year-old Elizabeth van Wyk, has fond memories of living at Eikenhof. Born on the farm in 1922, she says she was "always happy" there. She recounts stories of snakes in the Klip River, only visible when it stormed. She too attended school in the church building, like her nephew. She was married in the church and raised eight of her 10 children at Eikenhof.

She was sad at leaving. "They were nice times. We were all friends who looked after each other," she says.

Herbert Hofmeyr, an executive on the Ebenezer church board, says a land claim application was submitted to the government in 1995. "It has gone to and fro, with very little progress," he adds.

"According to records, the land was given to the church by the owner of the Lido Hotel in the late 1930s."

Battle for Joburg

A boulder with a chipped edge is evidence of Iron Age peoples in the area – the chipped flakes would have been used as tools and implements. Archaeological evidence reveals four Late Iron Age stone-walled sites, belonging to Nguni people, and one South African War stone rampart in the immediate vicinity.

The battle for Johannesburg, known as the Battle of Doornkop, took place across Eikenhof and neighbouring farms. It was, in the words of Thomas Pakenham in his tome The Boer War, one of the "last set-piece battles of the war".

"It was, in a way, magnificent," he states. The Boers lined the Klipriviersberg ridge, guarding the entrance to the town of Johannesburg. The British troops outnumbered them and advanced with confidence.

"The Gordons marched up, with the swing of their kilts and a swagger that only Highland regiments had, and then lay down quickly, beside Hamilton's staff officers, on the crest line facing the Boer positions."

Another kilted line got up and followed the first, then another. Soon the Boers opened fire on the lines. "The shooting became fast and furious. The British guns thundered; smoke from the burning grass drifted across the view."

The Gordons drew their bayonets and moved up the koppie to where the Boers were stationed. "The Gordons had the hill. They had lost a hundred men in ten minutes, but they had done the trick." The Boers retreated.

Map of the Battlle of Doornkop. British positions marked in red and Boer positions marked in green. (Amery, 1906 via HIA compiled by PD Birkholtz of Archaeology Africa in 2006)

On 31 May 1900, the British marched into Johannesburg and took possession of the Old Fort, thereby taking control of the town.

On the corner of the R554 and Kliprivier Road is a small walled cemetery. Within it is the tall gravestone of Captain Danie Theron, commander of the Boer Scout Corps. Theron was a public prosecutor. He used to ride his bicycle from Krugersdorp to Eikenhof to visit his fiancee. He became a strong cyclist and when the signs of war were imminent, he persuaded President Paul Kruger to establish a bicycle corps, by pitting a horse against a bicycle. The bicycle won, and it didn't need feeding. He died at Gatsrand in North West province, and was buried there but later moved to his family grave in Elandsfontein. His body was later exhumed and buried at Eikenhof, alongside the grave of his fiancee.

Jackson's Drift was one of only three crossing points of the Klip River in this vicinity. Several years after the end of the war in 1902, farmers requested a "wagon bridge". It was completed in 1913; the present bridge is most likely a later construction, according to the report.

The British went on to occupy Johannesburg on 31 May 1900. A blue plaque commemorates the official surrender of the town (The Heritage Portal)

Ebenezer Congregational Church

There are only three relatively intact original buildings left on the site – the church, and two dilapidated houses, which, together with the well, date back about 100 years. One of the houses was for the school teacher. The well is significant not only because it provided water for the community, but because the water was used for baptising congregants.

One of the dilapidated houses (Lucille Davie)

The church, begun in 1903 and completed in 1912, is known as the Ebenezer Congregational Church. It is still in use, with a congregation of 20 to 30 people.

It's a modest structure, built originally with mud bricks but later given wooden interior walls and ceiling, and corrugated iron walls outside, with an iron roof. Light filters through several curtained wooden windows, and the floor is laid with snatches of carpeting.

The church is divided into three segments – the church itself, about 20m by 6m; a vestry; and a small attached dwelling for the pastor. Outside the front door is a cast-iron bell positioned between two wooden posts.

Ebenezer Congregational Church (Lucille Davie)

Dr Phillips

The Khoisan community arrived in Johannesburg around 1894, just eight years after gold was discovered. The men worked on the mines as unskilled labourers, but the Kruger government provided very little for them.

Reverend Charles Phillips of the Congregational Church in Graaff Reinet in the Eastern Cape, arrived in Joburg in 1896, to preach to the fledgling Ebenezer congregation, then numbering 26 members, according to Harry Dugmore in his 1991 paper "Knowing all the Names: The Ebenezer Congregational Church and the Creation of Community Among the Coloured Population of Johannesburg 1894-1939".

"Ebenezer's rapid success in Johannesburg was, like that of the LMS [London Missionary Society] in the Cape, rooted in the provision of material resources which other institutions, including the state, were not prepared to provide," explains Dugmore.

"The first and most ‘material' reason for Ebenezer's popularity lay in its skilful exploitation of the lack of educational facilities for Coloureds in the ZAR."

Phillips developed the strategy of building a church, then renting it to the government for educational purposes, says Dugmore. From the money obtained, another church was built, laying the foundation for the construction of more churches.

By 1903, there were five Ebenezer schools with about 500 pupils. By the early 1930s, 25 schools for coloureds were established across the reef, with membership of Ebenezer standing at over 5 000, the fastest growing denomination on the Witwatersrand.

"Education was thus a highly desirable commodity offered by no other organisation save Ebenezer. By providing for this deeply felt need, Ebenezer created a sound basis for its enduring popularity."

Unifying effect

The Ebenezer church had a greatly unifying effect on the coloured community of the reef. Each church had a women's prayer group, a Wednesday evening class for adolescents, Sunday school for younger children, and junior and senior choirs. In addition, deacons, who could be any elected member of the community, would visit their own as well as other congregations, thus creating one large community across the reef. The church operated as a bottom-up structure, unlike other denominations.

The women's groups met on Mondays at 3pm, and women developed a great bond through these meetings. While political participation was stifled at all levels, everyone participated in the activities of the Ebenezer church.

"Ebenezer was the only real force in Coloured social life in [the] Witwatersrand of the 1920s and 1930s," says Dugmore. "As such, the church played an important role in developing the sense of ‘being Coloured' in the wider Johannesburg and Reef area, and of ‘being part of' a developing Coloured community."

That coloured community was nurtured in an "atmosphere of compassion and outreach" provided by the church, bringing together a "dispersed and often demoralised group".

The Ebenezer Congregational Church still exists in Joburg. Besides the Eikenhof church, there are four other churches scattered around the suburbs, with a membership of about 1 800 congregants – at Noordgesig and Eldorado Park in Soweto; Rust ter Vaal, in the far south of Joburg; and Ennerdale, on the edge of Lenasia.

For the meantime, the site remains a quiet stretch of veld, its secrets going back millennia to our Iron Age ancestors.

"It is the opinion of the author of this document that the study area's heritage resources will best be managed and sustainably utilised in a situation where the erstwhile residents of the property can return to the site which had been for many decades their home," records Birkholtz.

The developers will not, for the immediate future, drive their earth movers on to the farm. "The site may under no circumstances ever be destroyed or impacted upon," concludes the report.

Lucille Davie has for many years written about Jozi people and places, as well as the city's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.