Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Jacoba Anna Hendrika Sloet was my great-great-grandmother. My father met her as a boy. She sounded like a grouchy, imposing old woman, probably racist. He says she thumped her walking stick on the wooden floorboards when she wanted the maid to come, and was scornful of “kitchen Dutch” (Afrikaans), even though, as it turned out, her husband and her mother were Boers.

This was in Durban, maybe No. 46 Alpha Road in Umbilo, which was still standing when I went to try find it with my two young sons. It was one of the only remaining houses amidst new warehouses that had sprung up in a semi-industrial area close to the harbour that is now quite run down. I remember it as a simple, maybe lower-middle class suburban house from the early 1900s, with yellowwood floors, a fireplace and a small, muddy backyard. I think it was being used for office space. A woman with bleached hair and bright leggings let us in to look around. She seemed bemused by our interest.

“There was a big avocado tree we used to climb outside,” my dad said. “Was it there?” I wasn’t sure. She lived in a few places in Umbilo, sometimes I think renting.

She was a Dutch baroness. My gran always told me that, and I thought it was one of those stories people tell about their families that are passed on down the generations with no real evidence of being true.

But after spending the past 15 or more years on and off researching the blind-spot of my family’s history – on my paternal grandad’s side – I discovered it was true. Jacoba was born likely on a farm outside Calvinia in 1877, one of seven children (two died at childbirth or soon after). Her father was Arnold Frans Jacob baron Sloet van Lindenhorst. He had immigrated to the Cape Colony in 1861, at the age of 32 or 33.

Recent research has explored how the Dutch nobility sustained its ties and privileges. This is despite the disadvantageous changes in the political system in the Netherlands in the mid-1800s. In the case of Arnold Sloet van Lindenhorst and his descendants, this does not seem to have been the case. The Sloet van Lindenhorst line also died out in the Netherlands in 1915, leaving Arnold’s descendants in the Cape as the only remaining descendants of that branch of the Sloet family tree. As the Nederlands Adelsboek (“Netherlands Nobility Book”) from 1922 puts it: “Hieruit een tak uitsluitend in het Kaapland gevestigd, waarvan de leden Britsche onderdanen zijn” (roughly translated as: “From this a branch established exclusively in Capeland, the members of which are British subjects”). I think this makes the tale of some, even if minor, historical significance for researchers.

I discovered that the genealogy of the Sloet family, including the Lindenhorst branch, was well documented, and records were kept in the Hoge Raad van Adel (High Council of Nobility) in the Hague. The Hoge Raad was set up by King William I in 1814 in his efforts to re-establish the system of nobility in the Netherlands after the Batavian Revolution. The history of the family is centred around a small town in the province of Overijssel called Vollenhove. The family was descended from the third of three Sloet brothers who lived in the 1500s, themselves descendant from a medieval knight called Johan Sloet the Younger. He was from Vollenhove and appeared to play an important part in the politics of the time, as did a number of the Sloets who came after him. The van Lindenhorsts were one of eight branches of the family tree (the others being, for example, Sloet van Oldruitenborgh, Sloet tot Oldenhof, Sloet tot Oldenhuis, or Sloet tot Westerholt).

“Lindenhorst”, the manor house (havezate) in Bisschopstraat in Vollenhove once run by the van Lindenhorsts. A havezate was necessary to be recognised as a noble and to assume important political or administrative positions. (Beeldbankvollenhove.nl)

Arnold was born on Christmas day in 1828 in Hasselt, a small city near Vollenhove. He was one of seven children of Arnold Frans Jacob baron Sloet van Lindenhorst, whose name he shared, and Jacoba Hendricka Anna van Munnich, whose name was given to my great-great-grandmother.

Perhaps his parent’s death had something to do with his decision to immigrate to the Cape Colony – both had just died by the time he left – but the political and economic situation back home was also anything but settled for him. Constitutional changes driven by liberals in the Netherlands in 1848 had stripped nobles of the privileges they had previously enjoyed and which had been revived by King William I. This affected their positions in the civil service, which was how they had over the centuries exercised their political power in the face of an increasingly influential merchant class and that also seemed to offer a form of sheltered employment for family members. Arnold worked as a postal office clerk (“commies posterijen”), probably as a young man of 18 or 19. His father was a tax collector, and his grandfather, Coenraad Willem Sloet tot Slotenhagen en Lindenhorst, had been the mayor of Deventer, a town in Overijssel, as well as a postmaster in the town. He also held the position of Commissioner of Generality which referred to the lands that did not fall under any particular provincial jurisdiction. The Netherlands was also recovering from an economic crisis that seems to have reached its nadir in 1848, particularly in Overijssel, where riots were expected to break out – and perhaps the remnants of this helped to further unsettle the young baron’s already thwarted prospects.

Whatever the reasons, Arnold made the fateful journey. Four years after immigrating to the Cape, he married 16-year-old Elisabeth Maria Jacoba van Wyk in Calvinia. By then he was working as a teacher, probably at a farm school, lived in Agter-Hantam, and possibly off an inheritance. I don’t think he taught for long though, because they later migrated from Calvinia down to the Sutherland area, and then, at least in the case of his wife and their children, to Ceres. He would die at the relatively young age of 53 on the farm De Zyfer, with Elisabeth two months pregnant with their youngest son. The farm belonged to their good friends Gert Karsten and Hester Karsten who had been present at the baptisms of three of their children, including my great-great grandmother’s. The farmhouse where he likely died is now, by chance, a guesthouse in the Tankwa Karoo National Park.

The farmhouse on de Zyfer where Arnold died. (eGGSA)

Arnold’s estate inventory was filed the following year, in May 1883, and can be found in the Western Cape Archives. It lists:

1 [Huif] Kar en Tuigen (1 Covered Wagon and Harness)

1 Ladel (1 Drawer)

19 Schapen (19 Sheep)

9 bokke (9 Goats)

The inventory does not account for land owned, if there was any. He had a further £280 in cash in the bank and owed various people £53 but was also owed about £65.

His death left the pregnant 34-year-old Elisabeth, now a single mother of four, in a vulnerable situation. Her story is quite tragic. She appears to have been able to purchase at least two small lots of land in Ceres, as well as a farm for her eldest son near the town they called Wolvenhuis (also known as Little Prussia) where he farmed grain and sheep with his younger brother Jacobus.

Detail from a British Field Intelligence map from the Boer War showing the farm Wolvenhuis. (Stanford University)

But only a few years later, and after an earlier tuberculosis infection, she developed lupus vulgaris. There was little treatment at the time. The disease would plague her for the rest of her life, and the lesions evidently severely disfigured her (her estate papers described it as “facial cancer”).

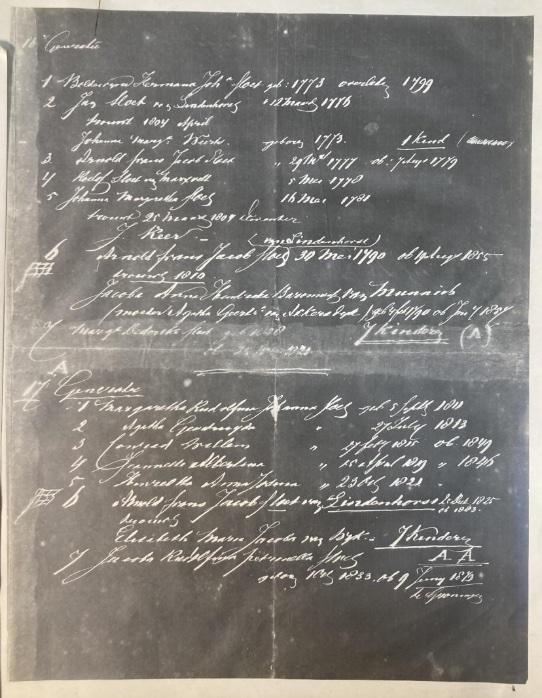

She appears to have grown increasingly desperate. In 1893 or 1894, ten years after her husband’s death, and barely a year after the death of Jacobus at Wolvenhuis from pneumonia (which may also have been tuberculosis), she wrote to the Hoge Raad van Adel in an attempt to confirm that she and her children could carry the titles of baroness and baron, and it seems inquiring about possible work for them. At the time, my great-great-grandmother was 16, and her older siblings 20 and 22. The reply from the Council was written on 6 April 1894 and addressed to “Baronesse Sloet van Lindenhorst te Kanolvonteyn”. It confirmed that the titles could be used, providing a detailed hand-written copy of the Sloet van Lindenhorst genealogy. The genealogy included seven blank spaces where the names of her children could be listed (although only four of them were alive by then). The letter “recognise[s] the addressee as belonging to the Dutch nobility”. It also recommended that Elisabeth contact a Mr. BH de Waal, who was the Consul General of the Netherlands living in Cape Town. It ends: “That person will probably be able to help you to get your children a job, and to gradually get them into a better position. If necessary I will send you a letter of recommendation.” I do not know if she followed up with this suggestion. Both her daughters, Elisabeth and Jacoba, would marry soon after.

A copy of the hand-written response from archivists at the Hoge Raad van Adel in the Hague showing the Sloet van Linderhorst genealogy. This was included with a typed version and covering letter from the Raad. (Cape Archives. KAB/ Accession/Ref. A6460

Elisabeth died in Ceres in 1918 at the age of 70. “The old lady”, wrote the executor to her estate, “suffered from facial cancer…for more than 30 years [and] was in a terrible condition at the time of her death.” Her death certificate describes her as a “boer vrouw”, and her estate then consisted of a “small property [which was mortgaged] and a few pieces of furniture”. She died probably dependent on her children and had not been repaying the mortgage on the property for some time. The executor stated that he was doubtful if many buyers could be found for the furniture and recommended that they were shared amongst her surviving children. The land was auctioned for £335 to cover the outstanding bond.

As for my great-great-grandmother, Jacoba Anna Hendrika, at 17 she married her first cousin, Petrus Jacobus Pyper, a “boer” from Sutherland. He joined the Matjiesfontein District Mounted Troops and was probably a scout for the British during the Boer War. After the war they anglicised their names to Jane Anne and Peter James and migrated to Durban (it seems via Kimberley) where Petrus worked as a rigger. They had three children. The eldest, a “sailor” with tattoos on both arms, travelled to Liverpool at the age of 18 and signed up with the Liverpool Pals (the 20th Battalion of The King's Liverpool Regiment) during World War I. He was severely wounded in 1916 when a ‘Jack Jonhson’ shell exploded near him and died just over three months after landing in France – five days after his 20th birthday. Jacoba is buried in Stellawood Cemetery in Durban alongside her husband, and her second son, also Peter James (baptised Petrus Jacobus). He followed in his great-grandfather’s family’s footsteps and entered the civil service, rising up to senior positions in the postal office. During World War II, he was the Assistant Director of Army Postal Services, East Africa Command. He ended his days as an Assistant Postmaster in Pinelands. Their third child, my great-grandmother Elizabeth Mary – baptised Elizabeth Maria Jacoba after her van Wyk grandmother – is buried apart from the family gravesite at Stellawood in an unmarked grave, the daughter of a baroness.

Post-script:

I have not done the big job of tracing all the male descendants of Arnold and Elizabeth. They would in effect continue the branch of the Sloet van Lindenhorsts that ended in South Africa and, I believe, be entitled to refer to themselves as barons, however anachronistic and even comical it may seem in contemporary South Africa. Their eldest, Hendrik, would have sons, and they had sons too (the name Hendrik Albertus was passed down the family line). An online genealogy search shows that the latest record of his male descendants appears to be from the 1990s. Their youngest son Arnold had at least one son. Arnold was, for a while, a shoemaker. He died in Vanrhynsdorp in 1953, divorced from his second wife, but a “rustende boer”.

The author welcomes feedback or corrections to this article, as well as any new information that may help develop the story further. He can be reached at: alanfinlay33@gmail.com

Above and main image: Jacoba Anna Hendrika Sloet with Petrus Jacobus Pyper on their wedding day in Ceres, 21 May 1895. She was 17.

Alan Finlay is a South African researcher and writer living in Argentina. He works in the field of media and internet rights.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.