Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In this article Peter Ball jumps across a few borders and looks at some of the history and politics of the Benguela Railway which runs for over 1300km across Angola.

On the 13th August 2014 the Benguela Railway, in Angola, was reopened throughout, between the port of Lobito and the town of Luau, near the border with the DRC, after a seven year long rehabilitation by the Chinese, reportedly at a cost US$ 2 billion. The line was reopened in stages, from the coast eastwards, starting with the Lobito to Huambo section, which had its train service restored in 2011. China has rebuilt the line under a trade agreement which exchanges infrastructure for oil (from Angola’s Cabinda oil fields). The rebuilding was undertaken by the management and construction team, the “China Railway 20 Bureau Group (CR20)”, with all the rails (50 kg/m), equipment, locomotives and carriages as well as the skilled labour force being sourced from China. The reinstated railway follows the same route as the original line conceived one hundred and twelve years ago, from the Atlantic coast to the interior of central Africa.

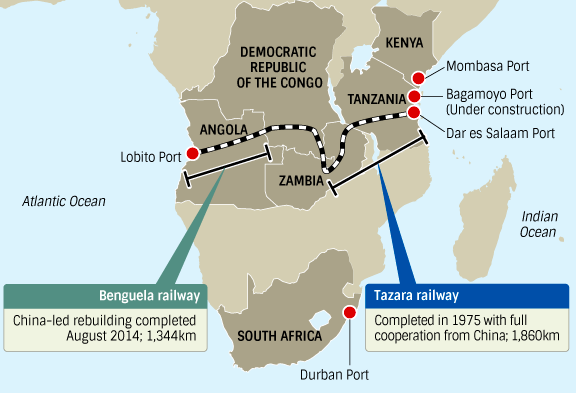

Map of Benguela Railway (and Tazara Railway in the East)

The devastating Angolan civil war, which lasted for 27 years, from 1976 to 2002, forced the closure of the entire railway line, except for the 34 km (21 mile) stretch between the coastal towns of Lobito and Benguela. The railway was under constant attack by Jonas Savimbi’s UNITA forces (backed by South Africa and America) in their conflict with the Marxist MPLA government (backed by Cuba and USSR). The tracks were torn up, bridges destroyed and locomotives and wagons wrecked. The political reasons for the war are well documented elsewhere, suffice to say here that the civil war was a great tragedy for Angola, but equally a great misfortune for its inland neighbours, Zaire (now the DRC) and Zambia, as the closure of the line cut them off from their nearest outlet to the sea. A Johannesburg newspaper headline at the time of the closure of the Benguela Railway read, “Mobutu and Kaunda: praying for train”; a reference to Joseph Mobutu of Zaire and Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia.

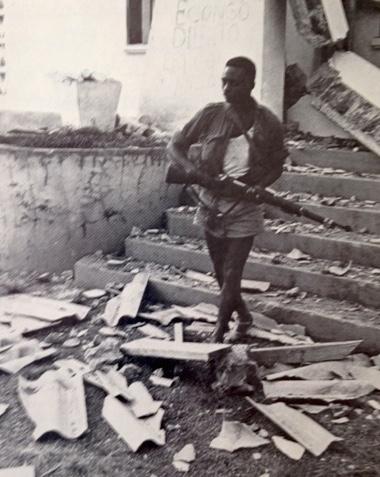

Angolan Soldier during the devastating Angolan War (Railways Southern Africa, May 1977)

The original Benguela Railway, known in Portuguese as the “Caminhos de Ferro de Benguela” or CFB was a privately owned company, with shares listed on the London Stock Exchange. It was incorporated in Portugal in 1902, and had a ninety nine year concession to build and operate the railway. The ownership of the railway has since reverted to the Angolan government, on the expiry of the concession on the 28th November 2001.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Benguela Railway was the brainchild of Robert Williams, a Scotsman and the managing director of Tanganyika Concessions (“Tanks” for short), a company with extensive mining, property and financial interests in central Africa. Williams was an engineer and entrepreneur (and also an associate of Cecil Rhodes) and he realised that a faster route to European and American markets was needed. He saw Lobito, on the coast of Benguela Province, as a perfect outlet to the sea for his railway. Although the primary purpose of the line would be the export of minerals, it would also serve to improve travel and communication within Angola, which was a vast country in need of development.

The line was built to the Cape Gauge of 3’-6” (1 067 mm), so that it could be linked with the existing railways of the “Copper Belt” and it would run inland, due east, from the port of Lobito to the town of Luau (formerly Texeira de Sousa) and thence across the bridge over the Luao river into the Congo (at Dilolo), a distance of 837 miles (1 345 km) from the sea.

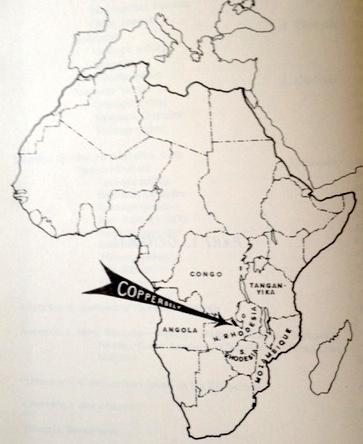

Map of Copperbelt (The Geology of the Northern Rhodesian Copperbelt, F Mendelsohn)

The construction of the railway began in 1903 and it would take until August 1928 (twenty five years) to reach the Congolese border, far longer than was ever planned. An account of the construction of the line has been given by H.F. Varian in his book entitled “Some African Milestones” and is well worth reading.

The railway was built and opened to traffic in sections, by working eastwards from the coast. The main physical obstacle, as elsewhere on the sub-continent was the steep climb from the coastal plain to the inland plateau (over 5 000 feet above sea level). The original alignment was unnecessarily difficult as it followed a surveyed route, stipulated by the Portuguese authorities, that was aimed towards the town of Caconda (south east of Benguela and never reached). This survey involved 2 miles of 1 in 16 gradient, up the Lengue Gorge, between Chivanda and Sao Pedro, necessitating the use of rack and pinion traction (by the Riggenbach rack system), this lasted until 1948, when an avoiding line was completed at 1 in 40. Later still in 1975 the town of Benguela was by-passed by what is now known as the Cubal variant on a gradient of 1 in 80.

Cubal was reached in 1909 and it was at this point that George Pauling Co. took over from Norton Griffiths as the main contractors for all subsequent contracts until the Congo border was reached. Huambo was established (at milepost 265 and 5 570 feet above sea level) with the coming of the railway in 1912 and soon became its hub when the workshops and railway village were built there. The town prospered with the railway and grew in size to become second only to Luanda, the capital. It was renamed Nova Lisboa (New Lisbon) in 1928, but has reverted to Huambo, since Angola gained independence from Portugal in 1975.

At the outbreak of the First World War, in August 1914, the building of the railway was halted at the town of Chinguar (at milepost 322 and 5 932 feet above sea level), this was due to the lack of the three M’s: men, money and materials, brought about by the hostilities in Europe. The construction of the permanent way resumed after the War and progressed slowly with only 68 miles of track being laid by 1923, when Silva Porto was reached (at milepost 390 and 5 643 feet above sea level). It was not until 1924 that work was taken up in earnest and from then until August 1928 the work was continuous until the Luao river (the Congo border) was reached, 837 miles from Lobito.

The delay in extending the line, after the War was not only due to the lack of the three M’s, but also because Jan Smuts the Prime Minister of South Africa between 1919 and 1924 was strongly against the CFB rail link to the Congo on the grounds that it would take away traffic from the line routed through Southern Rhodesia. He was eager for the Rhodesians to join the Union of South Africa (as its fifth province), as was Winston Churchill the British Colonial Secretary (from Feb 1921 to Oct 1922), however, in a 1922 referendum, the white male population of Southern Rhodesia voted instead in favour of responsible government under the crown (59% to 41%). Smuts himself was voted out of office in 1924 and South Africa’s new Prime Minister, Barry Hertzog withdrew any objections to the continuation of the CFB towards the Congo.

The Benguela Railway would form the major part of a direct route to the Atlantic Ocean for the export of copper mined in the Belgian Congo and Northern Rhodesia (nowadays the DRC and Zambia respectively). However the final connection with the Congo railway, the “Chemins de Fer Bas Congo au Katanga (BCK) would take another 22 months to complete. The BCK was responsible for the line from Tenke Junction, westwards to Dilolo near the Angolan border a distance of 324 miles.

The opening ceremony for the through route from Elisabethville to Lobito (a distance of 1 312 miles) took place at Dilolo Station, on the 1st July 1931, when a CFB special train steamed across the border bridge and stopped at the station platform next to a BCK train that had arrived from Elisabethville. Portuguese, Belgian and British officials were there to celebrate the occasion, which marked the forging of railway links across Southern Africa, from Lobito to Beira via Angola, Congo, the Rhodesias and Mozambique.

Prior to the opening of the line, the mineral traffic emanating from the “Copperbelt” was sent to the port of Beira, in Mozambique, via the Victoria Falls Bridge and Southern Rhodesia; a much longer route to Europe as ships had to sail around the Cape.

The CFB, up until the early 1970’s, was steam operated, with the locomotives being predominantly wood burning (80%). Cubal was an engine changing point on the line where the oil fired engines coming up from Benguela, on the coast “came off” and wood fired engines took over for the slog up to Nova Lisboa (now Huambo), 5 570 feet above sea level. As the line was originally laid with light rails (60 lb per yard,) the Beyer-Garratt articulated steam locomotive with its two engine units (chassis with wheels and motion) and its boiler slung between them was the preferred power; having the benefit of low axle loads with high power output.

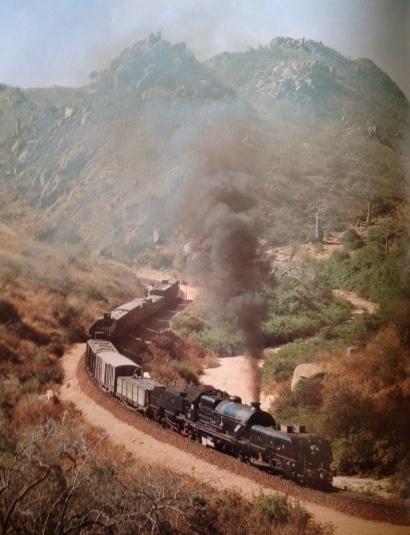

A wood burning Garratt locomotive (Railways Southern Africa, May 1977)

To the east of Cubal the CFB grew eucalyptus (blue gum) forests which were located at appropriate intervals along the line for the refuelling of the engines. The trees were fast growing and proved to be an innovative and economical solution to the problem of firing a steam locomotive. The only drawback when wood was used as a fuel was that although the eucalyptus logs were nearly as good as coal or oil in terms of the heat produced per ton, in terms of heat produced per square yard they were five times less effective. This meant that the logs were not only bulkier requiring additional bars being placed on the tenders (to retain the logs that were stacked up to the limit of the loading gauge), but also wooding stops were needed twice as often as would be the case for coaling stops. It also took two firemen to add the fuel to the fire!

For nearly five decades the CFB was well managed and maintained and was the largest employer in Angola with a complement of 13 000 employees and by the early 1970’s was handling 3.3 million tons of goods and minerals annually over its single track. With the prospect of a further increase in traffic the CFB was implementing a phase of modernization, which included the dieselization of services west of Nova Lisboa. By 1975 the CFB was only just fulfilling its potential and Lobito was handling 60% of Zaire’s copper and 45% of Zambian copper output. The civil war, between the MPLA and UNITA put pay to copper exports reaching Lobito, along the CFB and in turn threw the Zairian and Zambian economies into chaos.

The transport infrastructure of Southern Africa as developed by 1975 was a legacy of the colonial era (roughly 1875 to 1975) and the railways in particular provided the “realpolitik,” for the region, whereby the nations, although having different political ideologies, agreed on certain realities and material needs. One such instance was when the CFB was closed to copper export traffic on the 10th August 1975, soon thereafter the border between Zambia and Rhodesia, although officially closed (over political differences caused by UDI*), was re-opened at the Victoria Falls Bridge, so that copper exports could be re-routed to South African ports. I saw for myself in December 1975, whist sitting on the patio of the Victoria Falls Hotel, goods wagons being pushed from the Zambian side to half way across the Bridge to await the coupling up of a Rhodesian Railways locomotive, to take it southwards.

Fortuitously the opening of the Tazara Railway (a.k.a Tan-Zam) in July 1976 between Kapiri Mposhi, Zambia and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, would provide Zambia with another export corridor and lessen its dependence on her neighbours to the South. That is another story worth telling which will be related in a future installment.

Iconic shot of a loco on the Benguela Railway (Steam in Africa, Durrant, Jorgenson and Lewis)

*Footnote: UDI was the “Unilateral Declaration of Independence” by the white minority government of Southern Rhodesia (Rhodesian Front), under the leadership of Ian Smith, from Britain, on 11th November 1965; the last words of the declaration were “God save the Queen”.

Main Picture Credit - Photo by Peter Bagshawe appearing in "Steam in Africa"" by Durrant, Lewis & Jorgensen

References

- “STEAM in Africa” by A.E. Durrant, C.P. Lewis A.A. Jorgensen, 1981.

- “Some African Milestones” by H.F. Varian.

- “Accent on Conflict, Part 2: The Benguala Railway”, Page 13-17 “RAILWAYS Southern Africa”, May 1977.

- “Across Africa by Rail” from Mike’s Railway History

- Presentation given at the African Union, Second Conference of Transport Ministers, Luanda, November 2011 on the “Empresa do Caminho de Ferro de Benguela - E.P.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.