Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

A little-known story in South Africa is the remarkable effort under the direction of Professor (later Sir) Basil Schonland, Director of the Bernard Price Institute of Geophysical Research (the BPI), at Wits, to design and build a radar set within three months of the outbreak of war in September 1939.

Britain took the decision earlier in the year to inform its Dominions of the secret device (then called RDF) for detecting enemy aircraft and ships by means of radio waves. A senior scientist from each of those countries was invited to England to be briefed on the technology. South Africa chose to send a military man then serving in London. Needless to say, he was non-plussed.

However, the New Zealand scientist, Ernest Marsden, called into Cape Town on his way home where he was met by Schonland. During their three-day journey by sea to Durban, Marsden briefed Schonland on all he had learnt at Bawdsey Manor near Ipswich.

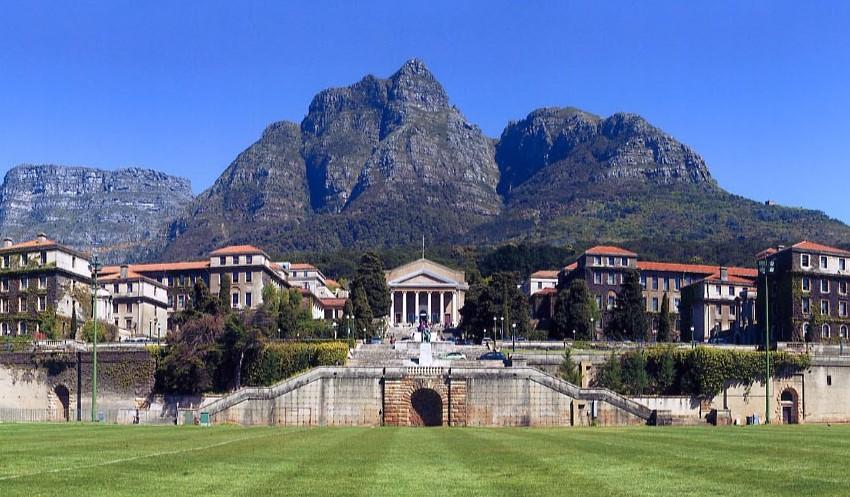

On his return to Johannesburg Schonland assembled his design team: engineers from Wits (Guerino ‘Boz’ Bozzoli), UCT (Noel Roberts) and Natal (Eric Phillips). They were joined by the BPI’s physicist Dr Philip Gane. Their task was to design and build a radar set in order, as Schonland put it, “to learn the technique”.

Within just three months they had succeeded in producing a working system, consisting of a separate transmitter and receiver, each with its own rotatable antenna. The first trials were disappointing. No radar “echoes” were received from a test target of copper mesh borne aloft by a hydrogen-filled balloon. The next test was stymied by the pilot of the SAAF aircraft – the intended target - deviating from a carefully planned course by choosing to fly over his girlfriend’s house instead.

Then on “Dingaan’s Day”, a public holiday on 16th December, Schonland and Bozzoli went in to Wits to make some adjustments to the equipment and to try it out. Schonland was in the BPI building where the radar receiver was located with its antenna on the roof. Bozzoli had the transmitter in the Wits Central Block, generally known as the “Great Hall”, with its antenna located on the roof. Their office telephones enabled them to communicate.

A recent photo of the Great Hall at Wits (The Heritage Portal)

With the equipment operating they slowly rotated their antennas, in synchronism, from north to west. Suddenly Schonland saw a “blip” on the screen; he shouted down to the telephone to Bozzoli and they reversed the direction of their antennas. Sure enough, there it was again. The two men immediately joined each other on the BPI roof and peered in the direction the antenna was pointing. There, about 10km away, was Northcliff Hill with its prominent concrete and steel water tower atop. Further tests confirmed that either the water tower, the hill, or perhaps both, were reflecting the signals from their transmitter and those reflections were being picked up and displayed on the cathode ray tube of the receiver. The radar was working!

Northcliff Radar Target

A recent shot of the Northcliff Water Tower (The Heritage Portal)

News of this momentous event soon reached the Prime Minister, General Smuts, and things then happened very quickly. Schonland’s civilians rapidly turned into soldiers, at least nominally. Radar was so secret and Smuts was adamant that South Africa would never let its British allies down by any breach in security, so Schonland and his men all went into uniform and the BPI became a military establishment with armed guards on duty.

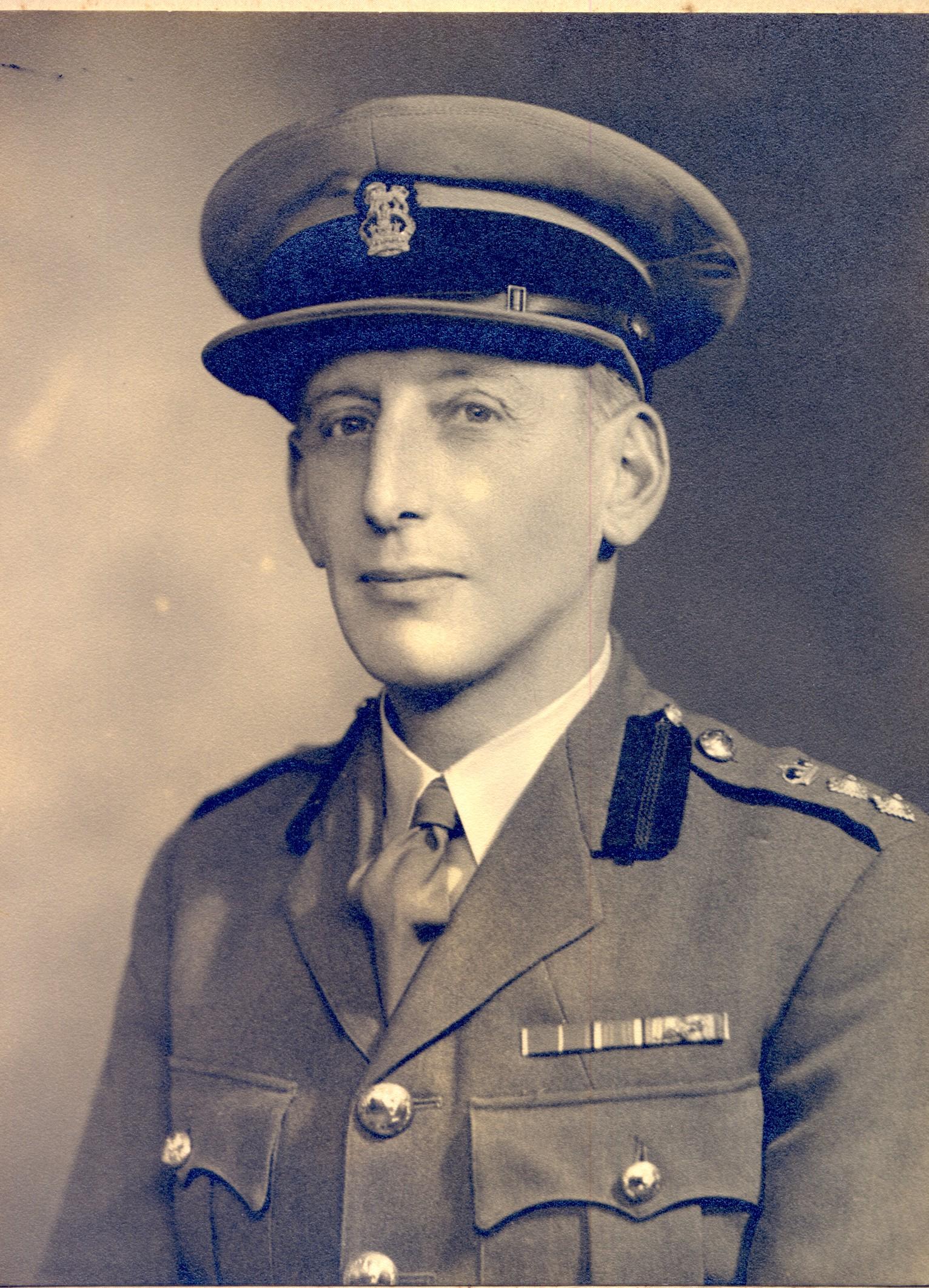

This was the beginning of what would become the Special Signals Services (SSS) of the South African Corps of Signals. Lt Col Schonland was its commanding officer, a role which took him back to his days during the First World War when he commanded men who were using wireless close to where South Africans had fought and died so valiantly at Delville Wood.

Basil Schonland

The so-called phoney war in Europe had by now become a fight for survival by Britain and all its radars were fully committed to that struggle. South Africa’s expectation that British radars would soon arrive to be deployed around the country’s extremely long coastline were dashed. It therefore became a priority for the SSS at Wits to become the research, development and production facility for the radars that the military authorities were calling for.

Immediately, young graduate engineers from Wits, Natal and UCT were recruited in large numbers. Radar training schools were set up on all three campuses and, in addition, women from the same universities were encouraged to volunteer as radar operators. Their commanding officer would soon become the young Nancy Blue, a niece of Colonel Freddie Collins, the Army’s Director of Signals.

UCT (Don Shaw)

By mid-1940 the production line, if one is permitted to give it that possibly pretentious term, was running. A completely re-designed radar set, called the JB1 by Schonland – its initials symbolising the city where it was born – was ready for deployment. However, events move quickly in wartime and instead of heading to one of South Africa’s ports the JB1 went north to Kenya, to a place called Mambrui,150km from Mombasa. The SSS not only designed the radar, they also operated it. Schonland himself took full responsibility for this first operational deployment. On a spot they called “South Africa Hill” they set up the JB1, to be powered by a slightly weather-beaten diesel generator purchased up there for the purpose. And they immediately hit their first problem.

At Wits the electricity supply came from Joburg and it was rock-steady; at Mambrui this was far from the case. However, a young man by the name of Frank Hewitt (subsequently Deputy President of the CSIR), who had, just a short time before, joined Schonland’s team from Rhodes in Grahamstown solved the problem by some intuitive engineering and Schonland was a very relieved man. This feat earned Hewitt some well-deserved plaudits from his commanding officer! The JB1 performed well and the SSS men spent six months in the wilds of Kenya defending an important airfield against incursions by Mussolini’s air force.

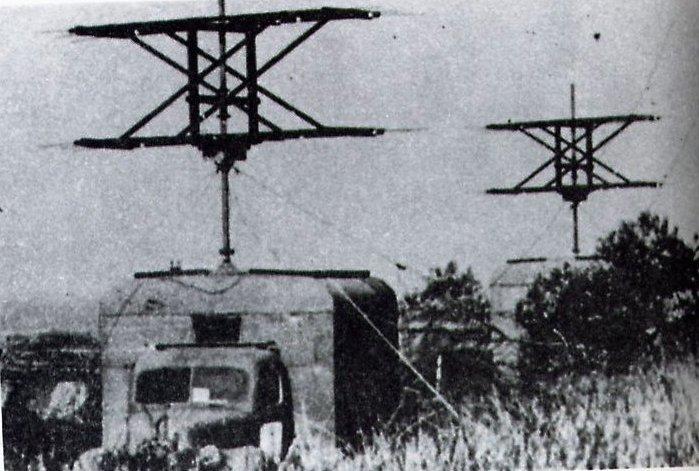

Bozzoli, now the SSS’s chief engineer back at Wits, though not quite churning out radar sets had already moved from the JB1 to the JB2 and soon to the JB3. Each represented a refinement of its predecessor with the JB3 being a fully mobile unit mounted in one of the army’s large vehicles with its impressive rotatable antenna on its roof. Word had reached the Royal Air Force that the South Africans had a radar set-up which was far more mobile than anything they possessed. And there was a serious need for it.

The Suez Canal was a frequent target for aircraft of both the German Luftwaffe and the Italian Regia Aeronautica and radar protection was vital. A trial of the SSS radar took place and it passed with flying colours. Immediately, three of the JB radars were flown to Eqypt where they were rapidly deployed along the Sinai coast. Again, those SSS men who knew every nut, bolt and thermionic valve of their radars inside out, operated and husbanded their equipment. Its performance, out to a range of 120km, was excellent and for the following twelve months the SSS provided the early-warning system that protected that vital Middle-Eastern waterway.

By now some British radars had begun to arrive in South Africa. Familiarisation and training were stepped at the three radar schools. The women operators were now a crucial part of South Africa’s coastal defence network. Radars were installed all the way round the coast from just south of the Mozambique border to Baboon Point 100km north of Saldahna. Places as familiar as Cape Point and Robben Island, Signal Hill and Melkboschstrand, or as exotic as Hangklip and Schoenmakerskop, Somersveld and Yserfontein soon had their radars looking out to sea. And their operators were nearly all women while, in many cases a solitary man kept the equipment ticking over or, more precisely, pulsing away with its antenna rotating on its tall tower above.

The SSS installed and operated radars in the aircraft of the SAAF and even went as far north as Italy where they found themselves using both British and American equipment as the Allied forces drove the Italians to surrender and the Nazis into retreat.

By the war’s end the SSS numbers had increased considerably. All told, more than 700 men and over 500 women had seen service in this most secret (and secretive) of South Africa’s armed services. In fact, to other women in uniform, and especially to the many civilians who encountered them, “SSS” simply meant Super Snob Squad because never was a word breathed by any of them about what they were doing!

SSS Radar Cape Town

About the author: Dr Brian Austin is a retired academic from the University of Liverpool. Born and educated in South Africa, where he studied Electrical Engineering at Wits, he spent a decade in industry, mainly at the Chamber of Mines Research Organisation where he led the team that developed the world’s first “direct-through-rock” underground radio system. He then joined his alma mater as an academic before emigrating with his family to England where he joined the Department of Electrical Engineering and Electronics at the University of Liverpool. Now retired he has long had an interest in military history and especially the part played by radio and radar in all conflicts. In 2001 his biography of Sir Basil Schonland, called “Schonland Scientist and Soldier” was published. He served as an officer in the South African Corps of Signals (CF) for many years. He was recently awarded the Master of Signals Commendation of the Royal Corps of Signals.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.