Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Below are edited excerpts from an article titled 'Stone Beehive Dwellings of the North-Western Cape'. The piece was written by James Walton and appeared in a 1961 edition of South African Panorama.

The road from Carnarvon to Williston in the north-western Cape winds across the semi-desert sheep country stretching up to the Karee Range. Dusty tracks through rocky outcrops of black basalt, weathered into gaunt, fantastic shapes and polished by the wind, lead to the scattered farmsteads. It is a hard, relentless country and one which promises little of interest; but in the homes of its early settlers it still retains one of the most fascinating architectural features in the whole of Southern Africa.

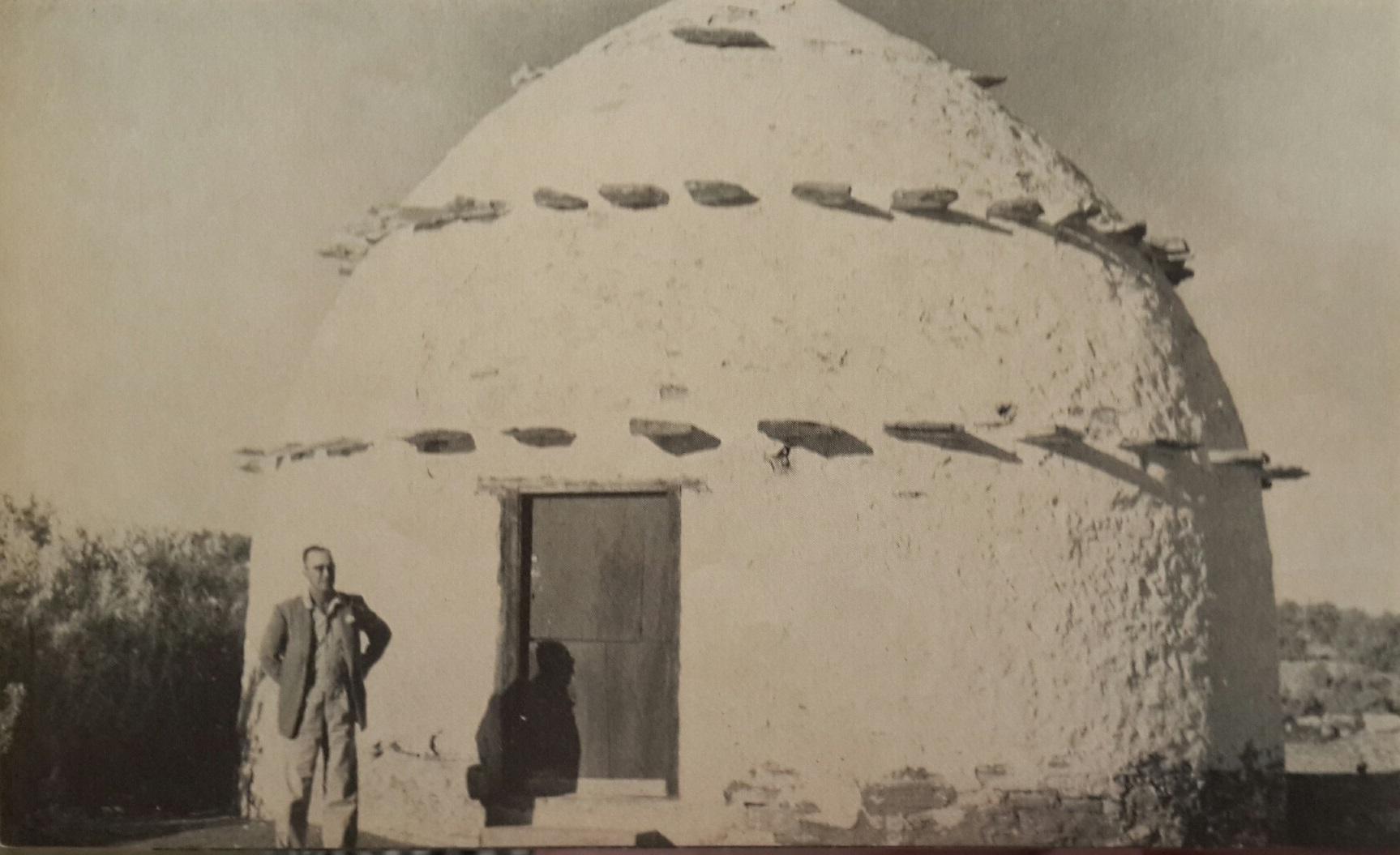

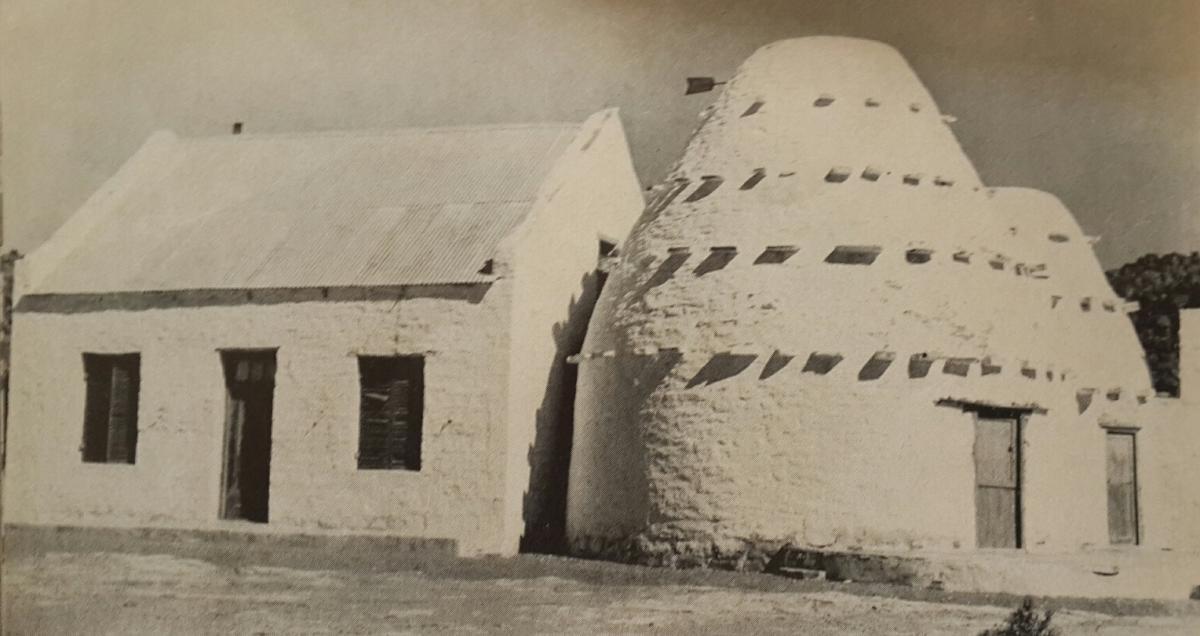

Schuinshoogte Corbelled House (South African Panorama)

In this stony, treeless, semi-desert country the first settlers built themselves giant stone beehive-shaped dwellings. And to look down for the first time on a farmstead such as Stuurmansfontein (see main image), with its glistening white beehives standing out sharply against the black basalt amphitheatre in which they nestle, is almost as remarkable as first seeing the famous beehive villages of Alberobello in Southern Italy or Gordes in the Maritime Alps.

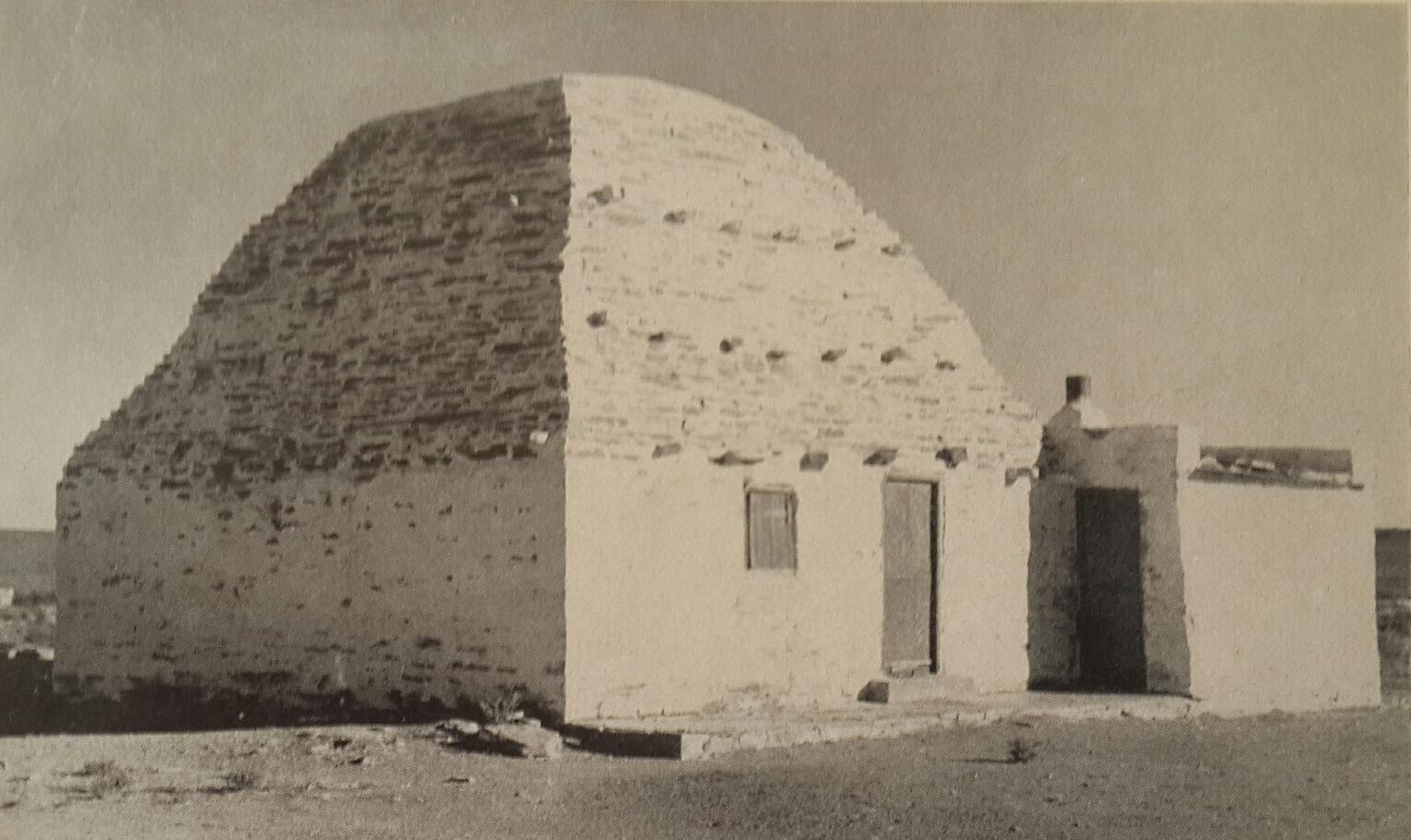

The huts are usually circular in plan, having an internal diameter of up to 18 feet, although a few are rectangular. The walls rise vertically to a height of about six or seven feet and then curve inwards gradually until they almost meet at the apex where the final opening is closed by a large flat stone slab.

Rectangular corbelled dwelling on the farm Arbeidersfontein (South African Panorama)

The method used, whereby each course of stones projects slightly beyond the one below is known as Corbelling and it originated near the Mediterranean thousands of years ago. It is interesting to reflect that the sheep-farmers of the Williston-Carnarvon district still occupy dwellings which are almost identical to the burial chambers of Mycenae.

Around the roof are projecting stones, usually three courses, though sometimes there are only two, and in the largest hut at Stuurmansfontein there are four. These stones serve as steps and anchors for scaffolding and were no doubt used by the builder when erecting the hut but they are useful still when repairs are being carried out or when the building is being whitewashed.

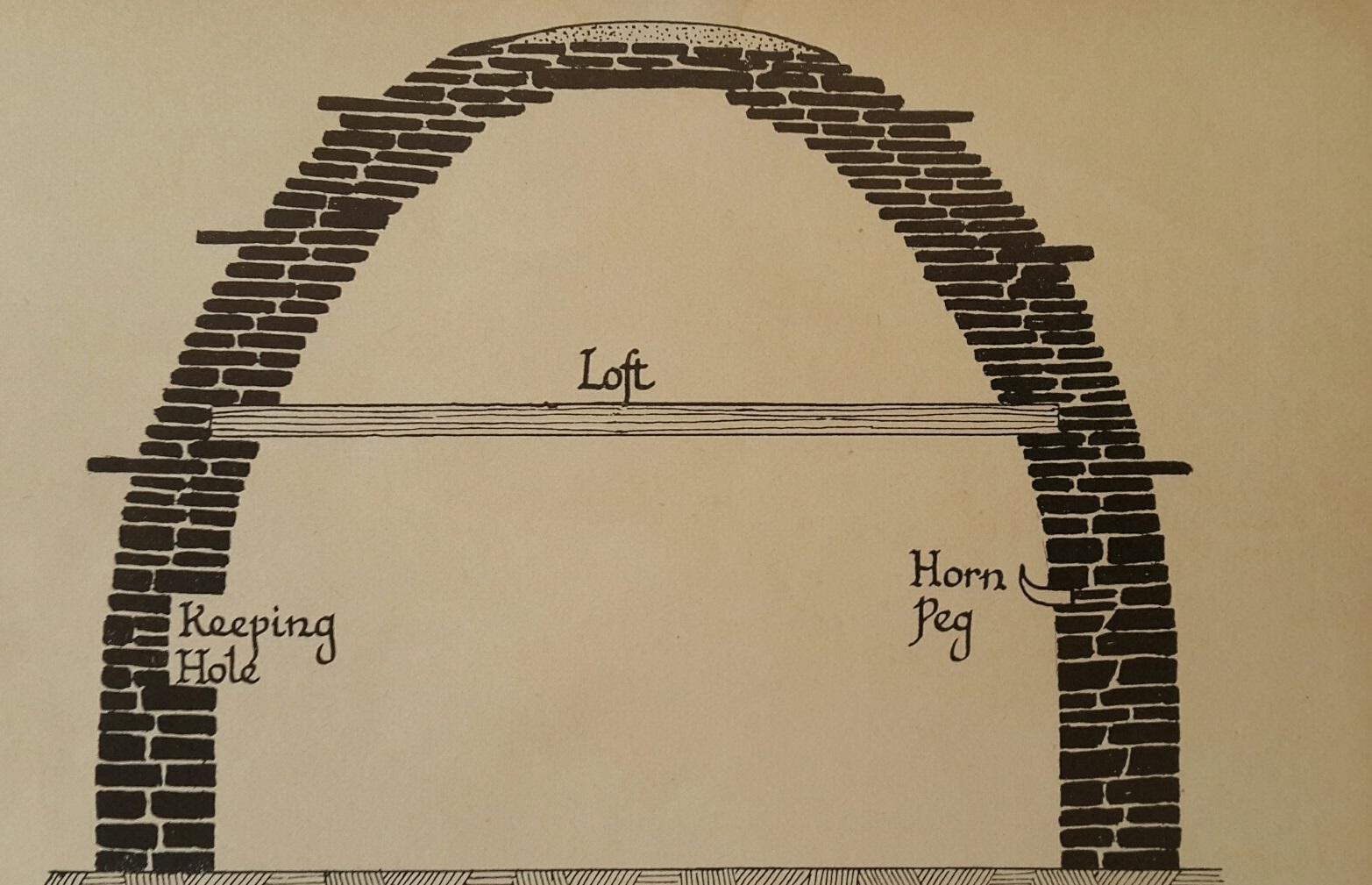

The door is the familiar halved stable door, and these doors, as well as any other timber required, were brought by slow ox-wagon from Beaufort West. Facing the entrance is a narrow window opening which was originally closed by small wooden shutters, some of which still remain. The floors were smeared with a mixture of clay and cow dung, rubbed smooth with a stone, and coloured and polished with a mixture of ox blood and fat. Small keeping-holes are let into walls, and usually a number of rough beams stretch across the arcs of the wall for drying meat or hanging clothes. An unusual feature is the use in almost every hut of horns of cattle or sheep or the horns of buck as wall pegs. No trace of fireplaces was found in any of the buildings, so all cooking must have been done outside.

Section across a corbelled hut at Schuinshoogte showing the horn peg and keeping hole (South African Panorama)

The corbelled beehive hut was, without doubt, the traditional home of the earliest settlers in this part of South Africa and the many survivals constitute one of the most interesting groups of South African "folk buildings". It would seem that when a farmer settled in the area he first of all built a circular or rectangular corbelled hut to serve his immediate requirements. Later he would add one or two more corbelled huts or tack on a small rectangular building with a flat or pitched roof.

Many questions come to mind as one gazes at these unusual dwellings. When were they built? Who built them? From whom did the first builder obtain the idea?

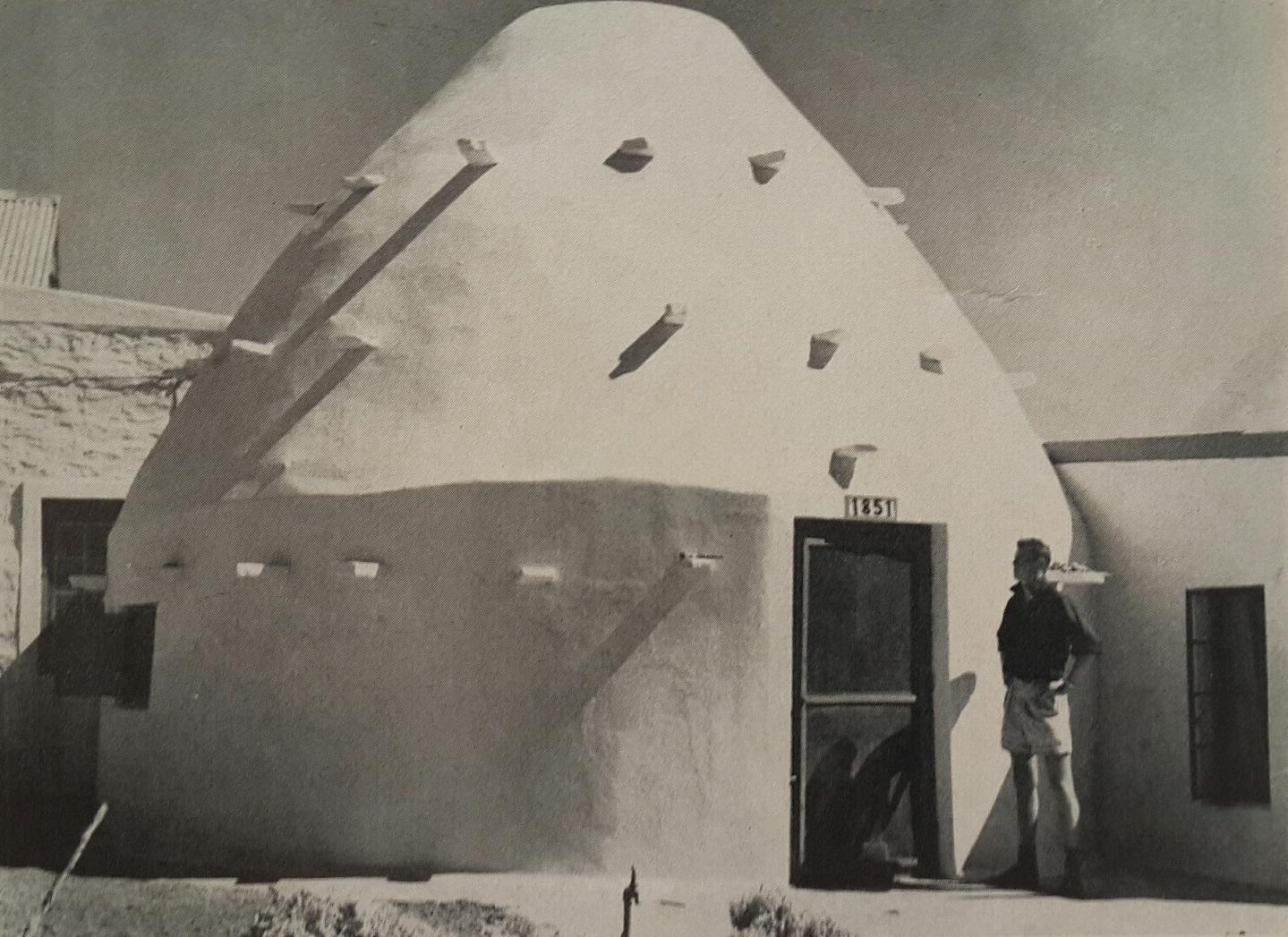

Only one is dated: a stone over the entrance bears the date 1851. Tradition has it that this hut was built in 15 days by the original owner with the help of a labourer. All inquiries so far have failed to elicit any information about the first builder.

Thokoboos Corbelled House dated 1851 (South African Panorama)

In a stony, treeless area such as the Karree Range the corbelled building is the ideal type of dwelling: refreshingly cool during the hot summer and retaining every bit of daytime warmth during winter nights. Did some building genius, finding himself in a country without timber but abounding in readily obtainable flat stone slabs, discover anew the technique which the megalithic builders in the Mediterrenean had evolved more than four thousand years before? It is a possibility which cannot be ignored but it is hardly likely when one considers that corbelled buildings in Italy, France, Spain, Ireland, Scandinavia, Syria and even Afghanistan and Greenland all arose from one common centre in the Mediterranean.

It is much more probable that some early settler, already familiar with the corbelled dwelling in southern France, or maybe in Italy, came to this bleak part of South Africa, which is so similar to the Vaucluse and parts of Italy where corbelled huts are still built and occupied. Without timber to build any other type and having previous knowledge of corbelling from his place of origin, he constructed for himself a giant stone beehive.

Whatever its origin and whoever may have been the fist builder, the corbelled stone dwelling developed mainly in the small area between Carnarvon and Williston where a number of examples survive.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.