Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The following article, adapted from James Ball's 2012 masters dissertation, looks at the practical compromise made by the apartheid government and the Johannesburg City Council not to 'relocate' black communities living in Pimville in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It is a bit heavy in places but a fascinating read nonetheless.

In 1904, after the outbreak of bubonic plague near present day Newtown, the African population in the area was moved to the farm Klipspruit twelve miles south west of the city. This settlement became Johannesburg’s first municipal location and in 1934 was renamed Pimville (after Howard Pim, a man who had dedicated a large part of his life to the ‘upliftment’ of Africans in Johannesburg).

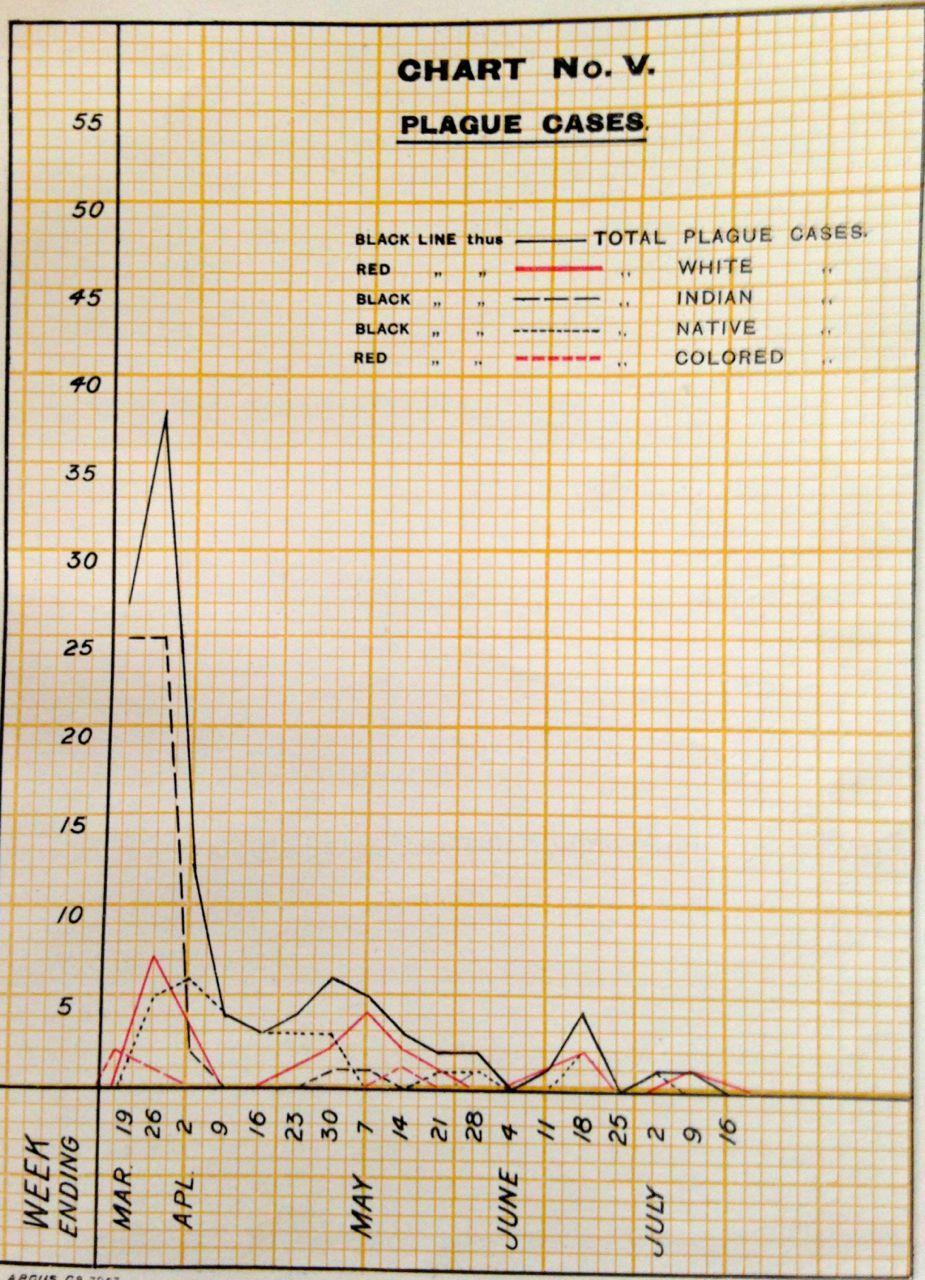

A graph of plague cases (1905 Plague Report)

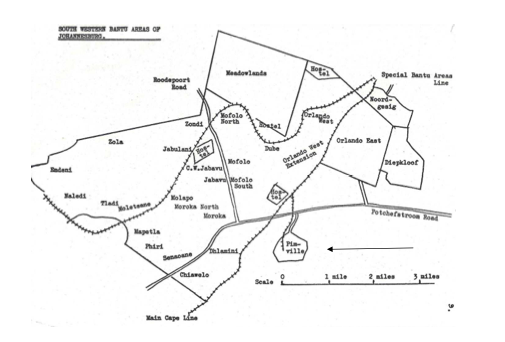

In the early 1950s a planning committee chaired by Mr FE Mentz responded to complaints from white residents in surrounding areas and recommended that the Potchefstroom road and railway be the dividing line between black and white (see map above and below). As Pimville fell on the ‘white’ side of this line the committee recommended its removal – a long-term project - so that ‘tensions between the races could be eliminated’.

Position of Pimville

The Johannesburg City Council appealed for the retention of Pimville as it was in the process of considering a complete relayout of the slum dominated area. Unsurprisingly, the request was rejected. The Council was also barred from incurring any further capital expenditure and the area continued to deteriorate. The Council was reluctant to accept this as the final policy and asked the Johannesburg Non-European Affairs Department (JNEAD) led by WJP Carr to prepare a detailed memorandum which was submitted to Government officials in 1955. The Department replied that nothing could be done until the Group Areas Board had made its recommendations to the Minister regarding the proclamation of group areas in and around Johannesburg. This was where the matter remained until July 1958 when the Johannesburg Non European Affairs Committee (JNEAC) decided to make renewed representations.

As Government policy had been firm on the issue, the Town Clerk recommended putting together the strongest possible case. It was agreed that the Council should not approach the government for the relaying of Pimville but rather for the resettlement of families who would have been housed on Diepkloof land that had been surrendered to the Resettlement Board for housing Africans removed from Alexandra. (In 1954 the Council negotiated an option to purchase a portion of the farm Diepkloof number nine from Crown Mines. The Resettlement Board asked the Council to forego their rights as the Board needed the ground for the proposed removal of Africans from Alexandra. The Council was reluctant to give up this land as it would have provided over five thousand urgently needed sites in an area relatively close to the city. In July 1958 the Council agreed to abandon its rights to acquire the land in spite of the demands of its own housing programme.) The following passages from a letter sent by the Town Clerk to Carr reflect the Council’s strategy:

It appears to me that the only possible approach to the Department of Native Affairs is that, the acquisition of Diepkloof by the Natives Resettlement Board having deprived the Council of the opportunity to provide housing closer to Johannesburg proper than the remote stretches of Doornkop, the Council should be allowed to develop available land fairly close to Johannesburg. But the emphasis must be on the intention to provide housing on this land for people who would otherwise have to be housed at Doornkop so that the relayout of Pimville itself becomes a secondary consideration.

As to the reasons given by the Mentz Committee for the original decision to evacuate Pimville in the distant future, the Council has already provided in addition to a buffer strip of the maximum width now required by the department (500 yards) a public road and an avenue of tall trees. The complaints that have been made are no more serious than those from the Europeans on the fringes of Doornkop and wherever we settle Natives the same complaints will arise. We shall have to make it clear that there will be no development along the present Potchefstroom Road until the new national road to the south has been opened. That will be the main argument but a secondary argument will be that the Council’s proposal will make possible the re-layout of the old village and the consequential avoidance of the necessity to pay £100,000 or more in compensation to families who might otherwise be dispossessed and move elsewhere.

The Council was eager to get permission to use the land adjacent to Pimville as it had a number of advantages including the following: 1) it was large enough to enable the JCC to provide around seven thousand houses; 2) it was already owned by the Council; 3) it bordered existing African areas; and 4) it was well situated along transport routes. The Council raised the matter with the Departmental Committee for Johannesburg (a committee set up to ensure that the council complied with Government policy) in August 1959 but negotiations were delayed due to the illness of the Chairman.

The impetus returned in 1960 when MC Botha replaced Mentz as Deputy Minister and in December he and Minister Nel visited the South Western Areas to see what was happening on the ground. Patrick Lewis, Chairman of the JNEAC gave a rousing welcome speech expressing his respect and gratitude to the Minister:

Mr Minister I feel you are endeavouring to carry out a policy which you believe holds the solution. I do not agree with many of the aspects of that policy, but I do accept your sincerity and I do believe you have a regard for the Bantu and wish to do right by him. I hope Mr Minister that you have the same feeling towards us, that although you may not agree with all our requests you will accept that they are sincerely made and that we, as much as you, are endeavouring in our small way to deal with the difficult problems of the Urban Bantu that are our responsibility.

Nel’s personal visit and the strong case put forward by the Council resulted in the Minister reversing the decision of the Mentz Committee – a move that would have been unheard of a few years earlier. (A number of constraints on the activities of the Resettlement Board in the Western Areas also provided motivation for the BAD to come to an agreement on Pimville. The ‘cleaning up of Sophiatown’ was being delayed by the shortage of alternative accommodation for Coloureds. The Board therefore wanted Western Native Township, which had been proclaimed a Coloured Group area, to be cleared to provide the required temporary housing. The Council also needed to provide alternative housing for the Africans from Western Native Township but had no land for such a purpose. It appeared as though the deviation of the ‘Mentz Line’ to free up land adjacent to Pimville could be the key to the whole problem.)

On hearing the news Lewis travelled to Pimville to inform the communities on the ground:

This is great news that I bring you. The Minister of Bantu Development Mr De Wet Nel has reversed a former decision of the Government that Pimville should become a white area and has agreed to allow us to build you new homes here.

In a report of the achievements in African affairs for the year 1960/61, Carr gave the following summary of events:

The protracted negotiations with the Government for the deviation of the Mentz Line further to the East to include the Pimville area within the South Western Native Area complex came to fruition during the Mayoral year with the receipt of the desired approval of the Minister of Bantu Administration and Development after a personal visit by himself and his deputy. The relayout of Pimville and the consequent rehousing of 7,000 families living under slum conditions in the township has, therefore, now become a matter of urgency and has been the subject of discussion with the Department of Bantu Administration and Development at a number of meeting of the Departmental Committee for Johannesburg.

Minister Nel received wide acclaim for considering the situation on its merits and enhanced his reputation as a man of reason and compassion. A key theme of Nel’s term as Minister, reflected in this decision, was his effort to understand the conditions on the ground in South Africa’s richest and largest city. Even Carr, who was highly critical of many BAD officials, praised Nel:

...there was however, one notable exception, that of Mr De Wet Nel. His tenure as Minister of the Bantu Administration Department was marked by humanity, compassion and humour, and although he did not depart from National Party Policy, he did apply it with a real sense of the difficulties and hardships experienced by ordinary Africans.

Although the retention of Pimville can be considered a success, it is important to note that over time the Council was stalled in its implementation of the scheme as housing loans from the Government dried up. This was largely due to the BAD’s focus on developing the homelands and reducing the attractiveness of urban areas in the hope of reversing urbanisation. The Mining Houses came to the rescue and in 1966 they organised a loan of R750 000 as a gift to Johannesburg on its 80th birthday to facilitate the completion of the Pimville scheme.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.