Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Following on from a recent Heritage Portal article by Carol Hardijzer about the fascination and value of ‘botched’ amateur photographs (click here to read), a friend of mine lent me some of her late father-in-law’s collection of colour slides taken on visits to the Kruger National Park in the 1960s. And when we say, ‘collection’ we are talking about a cardboard box filled with over eighty blue plastic Agfacolor slide boxes covering many trips to the Kruger National Park and other places. I haven’t counted the actual slides but at about 35 slides per box, this must be at least 2000 small format colour slides in their plastic mounts. They have not been looked at for 50 years. They are numbered, each slide written on with a pencil, but there is no longer a key. Some places are recognisable, while others are just a type of ubiquitous Kruger Park holiday image. And not that these photographs are necessarily ‘botched’ but are rather photographs taken by an avid, non-professional photographer, using an ‘ordinary’ camera, so no wide angle or zoom lenses, really just ‘happy snaps’.

My friend has been sorting through things after her husband passed away and this cardboard box of slides is all that remains of her father-in-law, Denis James Strever’s memories of his Kruger Park holiday trips, family weddings and places lived in. By chance, this box of photos languished for 25 years on a very high shelf in the house, while other boxes of old holiday and family slides were discarded. In the end, no-one knows what to do with this type of material, especially when they begin to dim in value as people pass away. Yet, even ordinary photographs can be fascinating when examined carefully.

I chose to re-photograph and examine 60 images from a 1967 Kruger Park trip (not all are shown in this article). The set epitomises the type of amateur photograph we have all taken in the Kruger National Park, like the one below of buffalo galloping across the road taken through the back window of the car.

Galloping Buffalo

The social and personal value of photographs

Photographs are a particularly durable and important form of visual record and are also a particular type of object that travels through time, creating the remembrance of forgotten persons and activities when viewed. Nancy Van House (2011) also argues that “photographs have agency as they ‘take the relay’ across space and time”.

In recent years there has been a surge of research in the humanities and social sciences, investigating photographic archives and links of photographs to personal and cultural memory. Research with photographs has deepened our understanding of how personal memory operates, how people make use of memory in their daily lives and how personal or individual memory connects with shared, public forms of memory. Images are also used in memory studies to better understand the neural basis of the memorial power of pictures, and in particular how pictures affect three components of recognition memory: familiarity, recollection, and the post-retrieval processes (Ally and Budson 2006).

Photographs for ordinary people include family photographs and albums, or slide collections or films taken of holidays. These stored images allow meaning to be created of past eras and people, and then the images may travel through time, often adding to the meaning that may have originally been intended by the photographer. Personal and family photographs have been found to be especially important in creating cultural memory, as well as for families and the construction of family narratives.

Both memory and photography involve the process of recognising images that may recall the past. Human memory itself is often characterized as an archive: a store of things, meanings and images, yet human memory does not take material or physical form in the way that photographs and archives can. Memory is not a photograph or a series of images and it is not a library or database where records might be retrieved. Rather, memory can be seen as a series of mental recognition processes through which the past comes to us, aided by items like photographs (Cross and Peck 2010). Other types of less directly personal photographs that invoke both personal and cultural memory include newspaper photographs, and now, images shown on the internet and video clips and on social media. When examined, all these images reflect the historical, cultural and political influences of the time (Devereux 2010).

For over 30 years the study of the ‘picture superiority effect’ of images being better than words for retrieving memory, has demonstrated that human subjects are more likely to remember items if they are presented as pictures rather than words, and this works well in product advertising.

One would have to work a bit harder to identify what memories Denis James Strever’s images invoke, especially in people who did not know Denis and his friends in the 1960s, or drove those cars at that time! Possibly the best we can do is to compare the old images with the Kruger Park as it is now, and use the images to think about the way almost everything has changed since then.

A selection of Kruger Park images 1967

In the set of 60 colour photographs I looked at, there are many silhouettes of giraffes, many photos of landscapes where there may or may not be a lion hiding in the bushes, and fortuitous photographs taken of something directly outside the car, just wind down the window.

A selection of photographs from the set

The sad blue hues of aging

Many of my friend’s old photographic slides have turned a blue/purple colour, apparently a common problem with Agfa colour slides. On cropping and enlargement, along with enhancing the contrast, many took on the appearance of moody landscape paintings and are unexpectedly exciting. There are also many scratches and dust particles which show up when the photo is enlarged. With Paint.net I could have adjusted the weird purple images to a sensible black and white, but then they lost their magic!

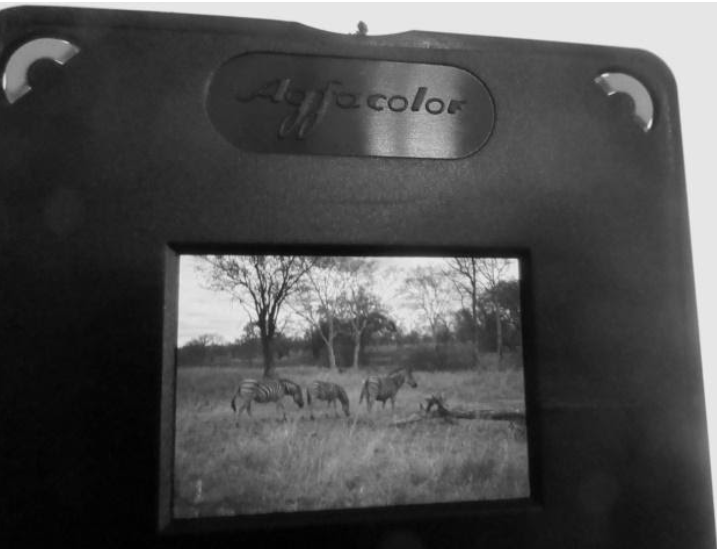

One of the Agfacolor slides, showing the blue cast in what was once a naturally coloured photographic image. The image below has been corrected to black and white. Photograph taken in 1967 by Denis James Strever.

The three images below by Denis James Strever appear like paintings and the age-changed colour of the slides creates new mystical landscapes that are nothing like the typical dried out winter landscapes of the Kruger Park.

Dried out winter landscapes

People, picnics and cars

There are many cheerful group photographs of family and friends enjoying their visit to the wild. Their names are no longer known. There are photographs of stop-overs, side of the road picnics and scenes with cars parked outside chalets in the Kruger Park and parked at places where visitors are allowed to get out of their cars. Many of the photographs are not quite in focus!

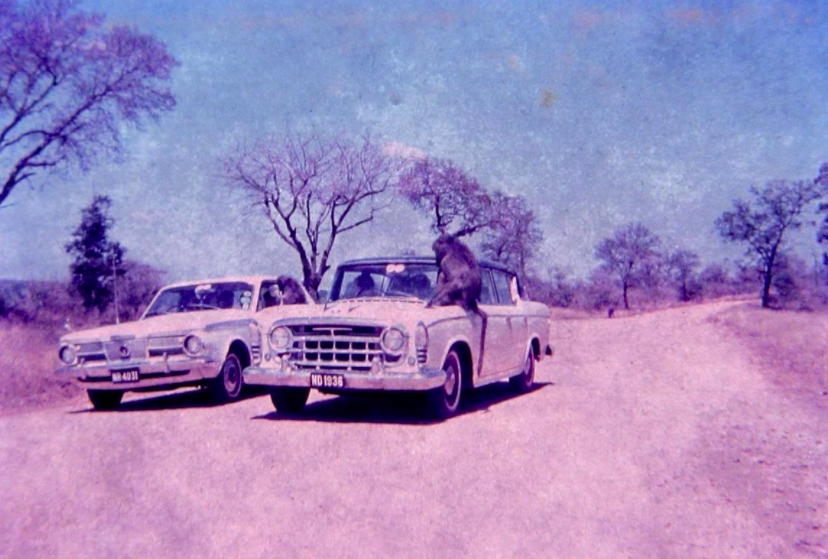

The images of the 1960s cars are enough to get the pulse racing, and my friend told me that her father-in-law really loved his Chrysler Valiant with its capacious boot, and he went all over South Africa with this car, along with his family, friends and all their children. All those people and their cars are long gone, and even the Kruger Park animals they photographed are gone, although of course, all their descendants remain.

A family picnic somewhere in the Kruger Park, 1967. Luckily the colour of this photographic slide has not changed too much despite its age (54 years). The cars are interesting, a Ford Taunus on the left and unknown two tone Chrysler model (?) on the right, with cute VW beetle in the background. Photograph by Denis James Strever.

Family stop-over in the Kruger Park, car boots open, everyone busy getting picnic things out of the car, 1967. The colour of this image has changed because of the age of the film (54 years). This is one of many photographs which are not in focus, yet it has a certain cheerful ambiance. Photograph by Denis James Strever.

One hut, one vehicle at an unknown rest camp in the Kruger Park, 1967. Perhaps someone will recognise this locality. Photographer Denis James Strever.

Cars touring the Kruger National Park, 1967. They must have stopped for too long, now have a pesky hitch-hikers exploring both cars. Chrysler Valiant on the left and unknown Chrysler model (?) on the right. Photograph by Denis James Strever.

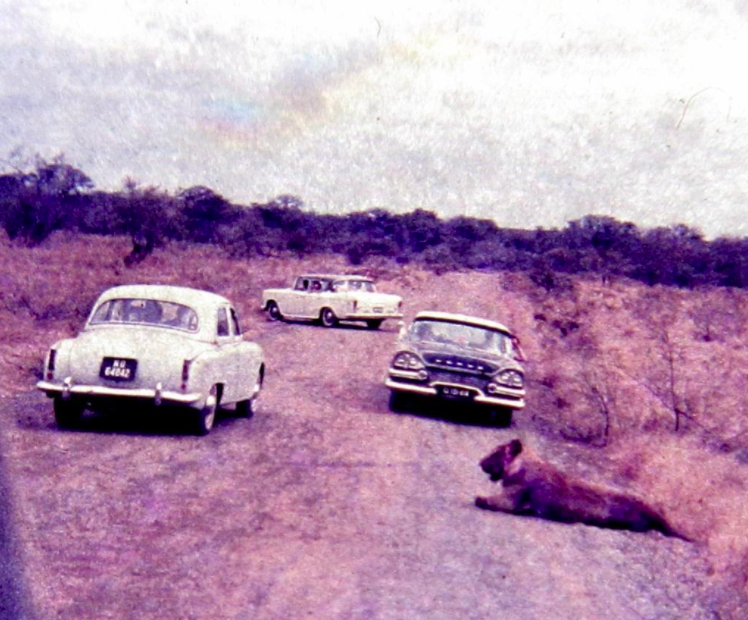

Family sedan cars from the 1960s with good lines on the outside and no electronics or other ‘fancy stuff’ inside the car. The lion looks like a tired, old carpet that has collapsed on the dry road. Kruger National Park, 1967. Photograph by Denis James Strever.

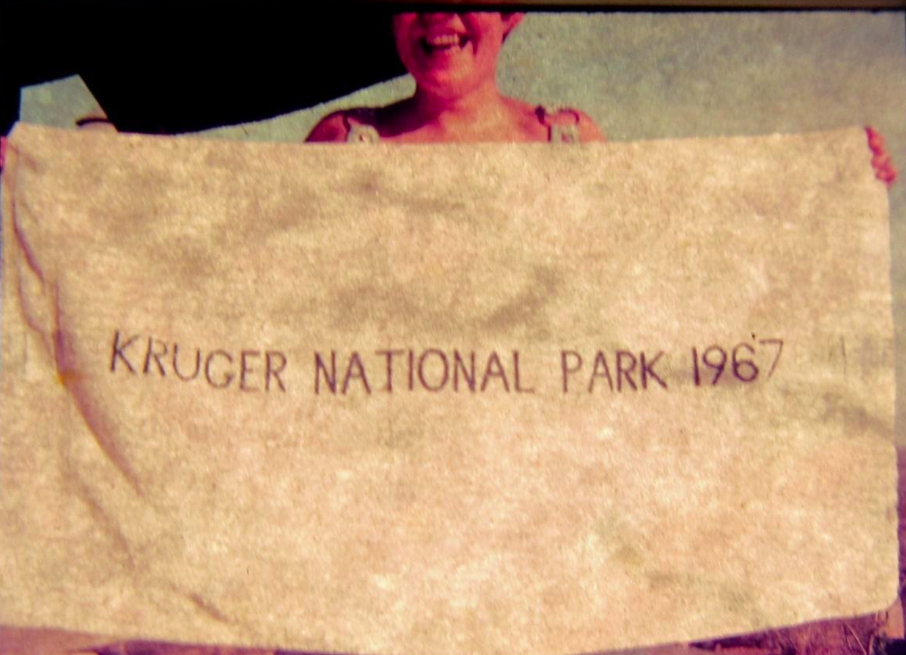

Interpreting the past from what is not thrown away

One could argue that there are ethical issues surrounding choices about what images or artefacts of the past are kept and what is throw away. If images are of an obviously important person or historic moment, they are likely to be kept by families or organisations. It is the ordinary, sometimes banal, images that are at risk. Yet any image could be important in the future, perhaps representing a forgotten viewpoint, a time when cultural values were different. The way that photographs are ‘read’ is also changing through research, with archivists and historians looking for the story behind the image, or the story that the image really tells. This is important in South Africa where the past was ‘contaminated’ by racist thinking and how this is often inadvertently evident in old photographs. In this way, the 1967 Kruger Park slides could be said to offer a window on the leisure activities of white South Africans in the 1960s, or the cars or clothes of the same period, or even gender and power relationships, and who is viewed or who is the viewer. There could even be potential to examine the state of the vegetation at the Kruger National Park at that time. Archivists and historians might definitely notice that there are no black South Africans in most of these photographs, and no black African languages on the signage.

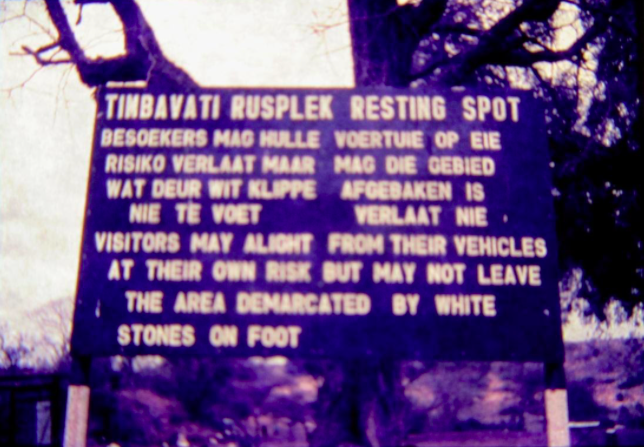

Sign at Timbavati picnic site, Kruger National Park 1967. Photograph by Denis James Strever.

This sign identifies the locality of the 1967 trip. The Timbavati picnic spot is near the junction of the S40 and S127, on the banks of the Timbavati River and within the Nkayeni Region of the park. What is interesting here is that Afrikaans is the first language on the sign, attesting to the Afrikaner dominance of the nation and this locality. I am not convinced that ‘resting spot’ is the way this type of place would be named in English, and is probably a direct translation from ‘rusplek’. The sign is not in any Black African languages and the idea that black South Africans could also visit the Kruger National Park was still many decades away.

Contemporary Kruger National Park

Just to get us up to speed with the now, the photograph below was taken at one of the Kruger Park resting places in April 2021. These resting facilities in the Park are all lovely, with good shops and restaurants, good ablutions and gas braais to hire. Seems the Kruger Park in the past was far less busy, far less commercial. Nowadays, during peak seasons, all the good viewings on the main roads can be clogged by large 4x4 vehicles, and it is essential to get onto the back roads if you want to see anything other than the rear number plate of the vehicle in front of you and humans leaning out of sunroofs. By studying the vehicles on display, something about the current affluence of South African tourists to the Kruger National Park can also be construed. In post-apartheid South Africa, there are almost as many black South African tourists in SUVs as there are white tourists.

Kruger Park Resting Place 2021 (Sue Taylor)

Over the intervening 90 years the Kruger National Park has become the most visited national park in Africa where wildlife viewing is sought by tourists as the main attraction. The number of annual visitors to the Kruger National Park in 1927 was 27 visitors and for 1959/1960 134 759 visitors visited the Park, with 247 969 for 1964/1965 and 306 345 for 1967/1968 (Wikipedia). So when Denis James Strever visited the park in the 1960s, visitor numbers were already increasing dramatically each year. More recently visitor numbers increased to 1.8 million in 2016/2017 and at a 6% annual rate of increase, visitors will double to 3.65 million by 2029 (Brett 2018). It might be time for SanParks to set a ‘carrying capacity’ for visitors or risk ruining the wonderful wildlife experience for visitors.

About the author: Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Her current interests encompass cities and urban greening, understanding degraded urban peripheries and researching writing about the disintegration (and rehabilitation) of industrial landscapes and buildings. She is currently a Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, QwaQwa, University of Free State (South Africa).

Sources

- Ally BA and Budson AE (2007). The worth of pictures: Using high density event-related potentials to understand the memorial power of pictures and the dynamics of recognition memory. NeuroImage 35(1): 378-395.

- Brett MR (2018). Tourism in the Kruger National Park: Past Development, Present Determinants and Future Constraints Department of Social Sciences University of Zululand, South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 7 (2).

- Van House NA (2011). Personal photography, digital technologies and the uses of the visual. Visual Studies Volume 26, 2011 - Issue 2: New Visual Technologies: Shifting Boundaries, Shared Moments.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.