Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Below is an incredibly powerful and detailed case study compiled by Dennis Radford in 1986. It looks at the restoration of 4 Anglo-African Street in Grahamstown and the creation of the Eastern Star Museum. The article was first published in Restorica, the old journal of the Simon van der Stel Foundation (today the Heritage Association of South Africa). Thank you to the University of Pretoria for giving us permission to publish.

It is widely acknowledged that one of the greatest problems concerning the conservation of architectural heritage, not only in this country but elsewhere, is the finding of a compatible new use for the historic older building. By compatible it is meant that the form, spaces and details of the old are not obliterated by the adjustments necessary for housing the new use.

The following article traces in some detail the process that was followed to ensure such a happy result. The building used as an example is No 4 Anglo-African Street, a part of a complex of buildings that originally made up the Eastern Star premises c1871 and which is now a working museum of printing. The chief purpose in presenting this information is to show how closely the principle and practice of conservation must be intertwined to ensure a satisfactory result.

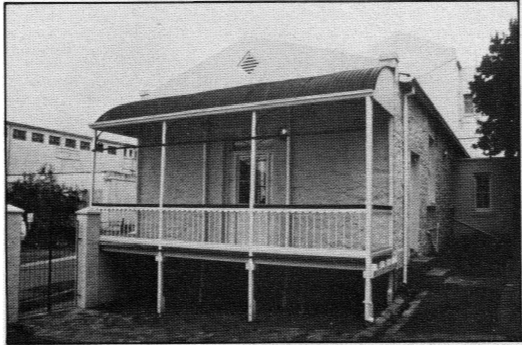

After restoration (Dennis Radford)

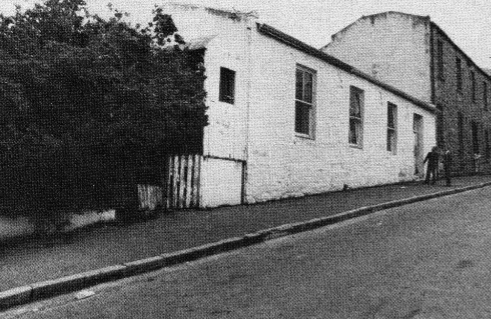

In early 1981, the author took a party of students and staff from the Department of Architecture at the University of the Witwatersrand on a field trip to the Eastern Cape to view and measure up in detail some examples of early Settler architecture. The group based themselves in Grahamstown. It was during this stay that they were shown No 4 Anglo-African Street by members of the local Historical Society who were concerned about its future and had discovered its links with the old Eastern Star Newspaper. The building as first seen by the author consisted of a large (15m x 7m) rectangular block lying parallel to and fronting immediately onto Anglo-African Street. This block is built of fairly thick stone walls laid in random rubble to eaves height and has plastered brick gables at the ends. The roof is of a shallow double pitch and is covered in corrugated iron sheets. Internally, the original single volume had been divided into a living room, passage and three bedrooms by means of light partitions which were faced with machine made tongue and grooved boarding.

At the lower end is a small verandah covered by curved iron sheets. At the back is a small two roomed brick wing under a lean-to corrugated iron roof. To this was added in very slight construction a bathroom and a W.C. The remainder of the site (13m x 25m) took the form of an L and consisted of a small overgrown courtyard and garden. The superficial appearance was extremely shabby and it was obvious that unless the building received a great deal of attention quickly, irreparable deterioration was about to set in.

Although the building is not very large or complex, it occupies a position of importance in Anglo-African Street. The character of this relatively narrow, sloping street, which leads off the High Street, is derived chiefly from the stone buildings which give it a very urban feeling. The effect that any demolition would have on this character can be gauged by the now open space opposite No 4. It was therefore felt that the preservation of the existing building was vital in townscape terms.

It was then agreed that a short report should be prepared and the Star Newspaper in Johannesburg be approached to assist in its preservation. This was done and the Argus Group, proprietors of the Star, reacted very favourably. They contacted the newly founded National English Literary Museum in Grahamstown whose trustees agreed in principle to run it as a museum of printing. In brief, the Star would buy and rehabilitate the building and hand it over, fully equipped to N.E.L.M. who would then assume complete responsibility for its running and maintenance. Its name, the Eastern Star Museum, would commemorate both its historical use and its links to the Star in Johannesburg. This agreement provided a realistic budget and viable future use for the building, both vital ingredients for its successful rehabilitation.

It was at this point that the author was approached by the Star and asked to act professionally as restoration architect. The initial brief was to visit the building again and report in detail as to its condition and as to whether the intended new function, that of a museum of printing, would be compatible with the building's essential character.

This inspection was carried out in April 1982 and a short report prepared which was submitted to both interested parties.The main points it covered were as follows:

- The roof, both the structure and covering was found to be original. There had been some conjecture that it had possibly been thatched initially. This would date the building to around 1860 as corrugated iron was not in general use before then. If this was true it must have been one of the earliest buildings in Grahamstown to be roofed in the material, a small but important item of historical interest. The novel wrot-iron cleats to the ridge seemed to confirm this still experimental stage in the use of the material.

- The existing front windows were clearly not the original, dating from c1900 but seemed to be of the same size as the original ones. They were in good condition and could easily be overhauled. There was no indication of the original, presumably small paned, windows.

- The existing front door was a stock Victorian four panel door but of an internal thickness and it was felt that it should be replaced.

- The external stonework was covered in many layers of ochre coloured lime wash. It was not recommended that it be cleaned for reasons that will be advanced below.

The main initial recommendations were as follows:

- The existing lean-tos (W.C. and bathroom) should be demolished and any new similar accommodation placed in a new block. Although the existing verandah dated from c1880, it added considerably to the external character of the building and should be retained.

- A new timber ceiling incorporating a lighting system was required as was a new electrical system. The suspended yellowwood floor needed some repairs and a substantial base for the proposed printing press would be required.

- The existing courtyard and garden would have to be cleaned and landscaped.

- In conclusion it was stated that "the building can be made into a very pleasant small working museum as is envisaged, without compromising its structural and historical integrity. It is a small building with a complex history, the results of which have mostly added to its character and which can and should be retained."

After this the next step in the process was the preparation of a users outline brief by the Director of N.E.L.M. This document, a model of its kind, was complete by early November 1982. It ran to 11 pages with 5 pages of appendices. A list of the section headings will give some indication of its thoroughness. These were: Aims, Functions Exhibits, Visitors, Staff and Major Spaces. Appendix A covered Exhibition - physical exhibits while Appendix B related to the treatment of site and buildings. A sketch plan indicating a rough layout of exhibits was also attached and in its scope and comprehensiveness it provided a firm basis for the anticipated form of the museum while giving the architect a clear and positive direction.

Two points derived from the brief are worth remarking upon at this stage. The first is that covered in section 2:1 which was as follows: "The building will be a combination of 'open air museum' and cultural technological history exhibition gallery, i.e. the building itself and its fixtures should be considered as an exhibit on the grounds of their historical and architectural interest, in addition to providing accommodation for exhibits". This and the subsequent clauses clearly provided for the building to become a living museum.

The second point, outlined in section 3:2 (Appendix B), put forward the need for archaeological research to underpin the hitherto scanty documentary knowledge of the building. This was eventually carried out.

Archaeological Dig (NELM)

The architect responded to the brief with a set of written comments. These pointed out that the principle of respect for the architectural and structural integrity of the building might impose certain limits on its future use although these limits would not be onerous. A sequel to this was the reiterated recommendation that some of the later 'tacked on' additions be demolished and that a secondary display and service accommodation be placed in a new separate building of a modest character. This is in line with current conservation theory which insists that a clear distinction be made between old and new both in form and structure.

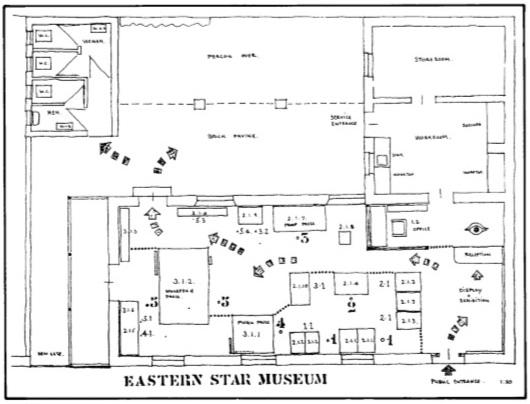

In the major display area the concept of a clearly marked route through the exhibits was proposed with the exhibits themselves being tactfully divided into operable and therefore nontouchable and the reverse. The sketch plan was taken as the basis for this route. It was noted that no record of the actual layout of the original Eastern Star premises was available but that a reasonably authentic environment, that of a small printing shop c1872 could be created.

The principle of recording the rehabilitation process as mooted in the brief was strongly supported and the possibility of mounting a small display in the building for the education of the public was suggested.

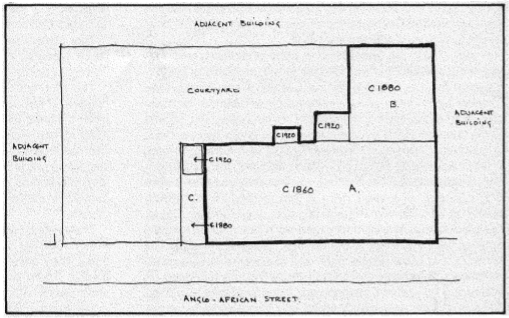

The assumed historical sequence was then advanced. Later research was to confirm this sequence.

Historical sequence (Dennis Radford)

The rest of the response was concerned with outlining the technical implications involved in some of the points raised in the outline brief. At this point sufficient documentary research had been computed to enable a clearer picture of the building's history to emerge. These findings can be summarised in the following way:

The earliest written reference to the building was in 1861 when it served as a classroom for St Andrews College. This use continued until 1872. The plot had been sold to Bishop Henry Cotterill in late 1861, it would therefore appear to have been built at this time. This is substantiated by collateral evidence such as a survey dated August 26 1861 by the Government surveyor who demarcated sections A.B. + D. of Erf 19 (the building stands on B). A prior survey of 1857 had indicated the proposed subdivision of Erf 19 which fronts onto High Street into several new lots including the strip that was to become Anglo-African Street. On Hoggar's plan of Grahamstown of 1863, part of which is reproduced here, only three buildings are shown on the east side of Anglo-African. These are, starting from the High Street, the proprietor of the Anglo-African Campbell's house, Waller's rooms (the present Post Office building) and No 4.

Portion of Hoggar's plan of Grahamstown of 1863

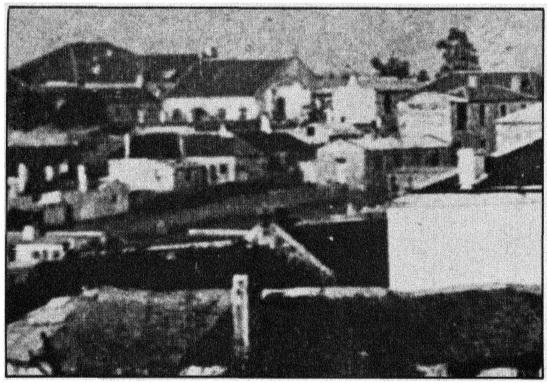

In a photographic panorama of Grahamstown of c1870 part of which is also reproduced here, the building is clearly visible. Both Hoggar's plan and the view plus another slightly later view not shown here, confirm that the earliest form of the building was that of a simple rectangle whose size and shape conforms to the core of the present building. The various openings such as doors and windows were also as now existing. There was no wing and verandah prior to 1880 as was previously conjectured. Nevertheless the building was clearly part of the Eastern Star complex in the 1870s.

Panorama of Grahamstown c 1870 (Albany Museum)

An interesting digression is that the various stages of growth apparent when looking at the facade of the house just above No 4 are also charted in the plan and on the views consulted.

The archaeological 'dig' as recommended in the users brief was also carried out but somewhat later. It concentrated on the courtyard with its remnants of walls and paving. No clear picture had emerged here and the possibility existed of finding artifacts which would prove the buildings usage and date. The dig was done by N.E.L.M. staff under the supervision of Mr Binnemann of the Albany Museum and will be reported in detail elsewhere. However the finding of fragments of slates proved its early use as a schoolroom.

Having assembled all the relevant material and with the users brief to hand it was now possible to undertake the architectural aspect of the programme. This was presented in the form of a large scale sketch plan and also a small cardboard model to show the three dimensional implications of the proposed rehabilitation.

Sketch Plan

From the plan it can be seen that, with the exception of the c1920 additions, the building was to be kept as it was. The philosophy behind this was twofold, in practical terms it would have served little purpose to demolish the wing and verandah, both were not incongruent with the oldest part and could serve any required subsidiary functions with ease. On a more abstract level, there was the desire to preserve as much of the building's history as was compatible with its new use.

The internal partitions were to be demolished and the integrity of the large internal space, the original schoolroom, was to be reinstated. This room would become a printers shop through which small groups of visitors would be guided and where they would witness the sequence of operations typical of the production of a small newspaper C1870. The climax of this process would be the running of the great Wharfedale Press (3.1.2. on plan). The original Eastern Star machine had been dismantled but a contemporary one had been obtained from England along with other items.

The layout follows that prepared for the users brief but modified to allow for both the limits of the space and an easy route through the exhibits. This route ends at the existing back door which in turn leads out into the pleasant courtyard and where a new, modestly scaled, structure was to house cloakrooms and a secondary exhibition. The remainder of the site was to be grassed and landscaped in a low maintenance way.

The two rooms of the wing were to be a private preparation and storage area. Service to this was via a new lower gate and through the courtyard. Security and a desire to maintain the 'hard edge' of the street indicated the need for a high wall down the remainder of the frontage. Stonework was out of the question because of cost, so a thick bagged brick wall with a traditional mortar capping was designed instead.

Perhaps the most controversial thing about the external appearance of the rehabilitation is the decision to keep the light cream limewash finish, especially as the other older buildings are of exposed stonework. This was done for the following reasons: The existing stonework is in random rubble (irregular sizes without courses) and was probably built with the reject pieces from the house next door. It is therefore almost certainly inferior in quality and, if the accumulated thickness of the paint is to be believed, was painted very soon after erection. The fittings of the present windows, although of almost the exact size of the original ones, had also damaged the openings which are now framed in plaster and not in stonework as is usual.

The programme as outlined above was then presented to the Steering Committee along with a preliminary builder's price which had been obtained by means of a rough schedule of work. It was accepted in toto, the only modification being to the new building where the accomodation was trimmed to effect some necessary savings. A simpler building, the present, was designed and after the production of detail drawings and a specification, a firm quotation was obtained. This proved acceptable to the clients and work was commenced in January/February of 1985, the completed building being handed over on 1 October.

What emerges strongly from the process as narrated above is the need for a 'grass roots' involvement in conservation by local people or organisations whose care and knowledge can provide the very necessary initial basis or kick off point. Having an idea for a viable use and then a realistic budget with a sponsor or sponsors would appear to come next along with the need for 'professional' intervention. By professional it is meant not only the restoration architect but also a clear sighted user. Most important of all though is a continual all round sensitivity to the building's integrity and all of its history. This history must also be thoroughly researched.

The necessity of a thorough users brief has also been stressed. This must be the foundation for any integrated architectural/user programme. Lastly, but certainly not least, is sensitive craftmanship for which a good architect/builder relationship is usually an important ingredient. All this is well known but it is worth repeating especially as the process works so well.

Acknowledgements

No work of this nature is the exclusive domain of a single person therefore the involvement of others in the project must be gratefully acknowledged. Dr Eily Gledhill of Grahamstown for first discovering the building and its association with the Eastern Star. The Argus Group, for the funding of the project, in particular Mr H. Tyson then Editor and Mr J. Nuttall, Manager of the Star, for their personal interest in getting it completed. The National English Literary Museum who are operating it as a 'living' museum and whose director, Professor Andre de Villiers, through his enthusiasm and knowledge of printing provided much of the expertise necessary to turn it into a realizable project. Pat Going of Erasmus, Rushmere and Going, architects of Grahamstown, who undertook the thankless task of day to day supervision. Lastly, Heunis Construction of Grahamstown whose craftsmen turned drawings into reality. For this rehabilitation and conversion the author is honoured to have been the recipient of a 1986 Herald Architectural Heritage Award.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.