Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Many of the railway stations and railway lines of Johannesburg no longer have the network of wires, cables, beams, insulators and transformers above the tracks that they used to. The sky is clear above these stations – and this is not a good situation.

I started my investigation of Denver station using Google Earth to explore the area between Jules Street and the railway line and came across the rather impressive 1930s Station Hotel in Berlein Street which had once served passengers from Denver station. I decided to go and take my own photographs of the hotel and the Denver station precinct and get a sense of the atmosphere of the place, as well as investigate the impact of time on this old Johannesburg hotel. Denver station is on the railway line that links Johannesburg’s Park Station to Germiston and the East Rand.

While I had hoped to write about the picturesquely ruined Station Hotel and quaint Sixth Street station precinct at Denver Station, my visit led me to appreciate a more notorious concern: the destruction of South Africa’s urban commuter rail network (MetroRail) through cable theft and vandalism. In recent times, railway infrastructure has been deliberately stripped for its cash value, specifically valuable electrical infrastructure (notably copper cables) and anything metal along the railway lines and in the waiting rooms. The same has happened with the national freight rail system.

The railway line that NZASM built

Denver Station is one of the stations on the railway line south of the Johannesburg CBD, built by the Nederlandsche Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg-Maatschappij (NZASM). This Dutch company was established in 1887 to build the railway lines linking the Witwatersrand to the Mozambique port of Lourenço Marques. This extensive urban aspect of this rail system was built to facilitate the movement of coal, construction materials, other goods and provisions to the Witwatersrand gold mines and to the thriving new city of Johannesburg. At the time that gold was discovered, both the Transvaal and Free State were agrarian economies and relied on wagon transport. This transport system quickly became inadequate for the rapid industrialisation process underway (De Jong 2015).

The rail section linking central Johannesburg with the rapidly developing East Rand and West Rand was known as the Rand Tram. By 1900 the Rand Tram was the busiest railway line in the Transvaal and the Johannesburg-Elandsfontein (Germiston) section carried the heaviest traffic. On account of its relatively short length (81km) in a busy urban area, the Rand Tram proportionally had a large number of stations and halts compared to other NZASM lines (De Jong 2015).

Old Park Station, Johannesburg, 1900. (DRISA)

This structure was rescued and is now housed in Newtown (The Heritage Portal)

The Rand Tram Line stations and halts from east to west were (present name indicated between brackets): Springs, Schapenrust, Brakpan, Boksburg (Boksburg East), Vogelfontein (Boksburg), Oostrand (East Rand), Heidelbergpad (Angelo), Halfweg (Delmore), Knights (disappeared), Elandsfontein (Germiston), Driehoek, Simmer & Jack (disappeared), Geldenhuis, Cleveland, George Goch, Jeppe, Doornfontein, Johannesburg Park (Johannesburg), Johannesburg (Braamfontein), Fordsburg (Mayfair), Langlaagte, Claremont (Bosmont), Maraisburg, Florida, Roodepoort, Witpoortje, Luipaardsvlei, Krugersdorp (De Jong, 2015). While the nearby Cleveland station is mentioned in the de Jong article, the Denver Station (built 1903) is not. In fact, it is difficult to find any reference to Denver Station and the Station Hotel online and in various heritage databases.

Much of the original NZASM architecture of the early Rand Tram system has been lost, largely because of the continuous modernisation to cope with the increase in frequency, weight and length of trains. Only two station buildings of the Rand Tram have survived: the old Krugersdorp station and the remnants of the old Park Station (De Jong (2015).

Old photograph of Krugersdorp Station

Destruction of the railways in Gauteng

Many articles have now been written about the on-going theft of freight rail infrastructure across the length and breadth of the country, affecting all of the national and urban rail transport corridors. Hundreds of kilometers of copper cables, track, and other general infrastructure have been stolen from the freight rail system, costing the state billions in potential revenue and proving almost impossible to control (Transnet Freight Rail 2021). Just when South Africa should be moving towards rail transport for freight for climate change reasons (fewer emissions), freight customers are seeking alternative delivery methods, which means trucks and roads, or paying for private security. The same level of theft and vandalism has happened to passenger rail in Johannesburg and other urban areas.

The railway line to the east of the Johannesburg CBD, along with others in Gauteng, is in ruins. In 2020, just before the collapse of MetroRail services in Gauteng, Prasa (the Passenger Rail Association of South Africa) reported that over 672 000 daily train commuters had been left stranded by the collapse of train services across Gauteng, with 1833 incidents of train stations having been vandalised over the past three years with a replacement cost in excess of R2 billion. The cancellation of rail trips has resulted in a financial loss of R173 million per annum to MetroRail (Waters 2020). To repair the passenger rail to full functionality would cost in the region of R2 billion, says Prasa, and yet to get them back to working order may be a challenge, given that they could be vandalised again. It could be a long time before most of these passenger train services resume in Gauteng (Simelane 2021a,b,c). Privatisation may be the only way (Transnet Freight Rail, 2021).

In Johannesburg, there is huge poverty which means that people are desperate enough to climb tall masts and remove pieces of electrical equipment and copper wires to raise some cash. It also seems that the electricity supply to stations was switched off during the Covid-19 lockdowns in early 2020, facilitating the theft of electrical items.

Denver Station and the Station Hotel

During the Great Depression, national economies around the world suffered, including South Africa. The decision to go off the gold standard saved South Africa's economy and South Africa prospered after this move. This success was reflected in a 1930s building boom. Architectural projects in prosperous Johannesburg during this period were ambitious and grand, with a strong Art Deco influence. The Denver Station Hotel follows this trend, albeit on a smaller scale.

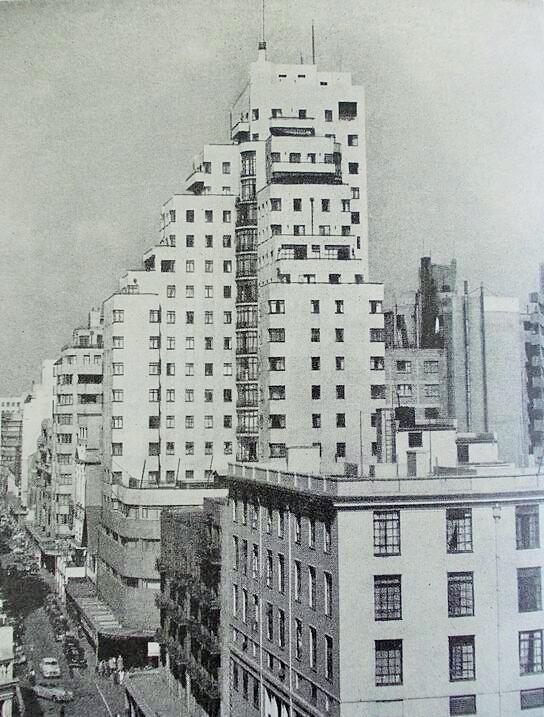

The iconic Art Deco Ansteys Building

The suburb of Denver was laid out in 1903 on land acquired from the Bezuidenhout family and the area was originally intended to be market gardens. Before and after the Second Boer War, several American mining machinery firms built offices there and the new suburb was named after Denver, capital of Colorado, as a result (Wikipedia). Nearby Cleveland was also named for the same reason. Currently, only a small portion of the suburb of Denver has residential zoning and most of Denver consists of industrial land and informal settlements (Wikipedia). Cleveland is a light industrial area, also established in 1903, but now with many overt and covert informal settlements. Denver Station must have also been built around the early 1900s, although I haven’t found a date. The Station Hotel was built later, judging by its architectural style.

The Station Hotel at Denver Station

The two storey Station Hotel was built in the late 1930’s building and has a typical splayed corner and cantilevered balconies. It was built after the rows of small Victorian-era shops in the station precinct. The shops would have been built around 1903 when the station was established. It would be time consuming and difficult to find the present owners of the almost-derelict rows of shops and the hotel. The Station Hotel and nearby old shops and a nearby apartment building are no longer used by station commuters, but are occupied by families. People live in the Station Hotel although it is no longer a hotel.

The Station Hotel (Sue Taylor)

The name of the hotel still remains on the very shabby building (Sue Taylor)

South face of the once grand hotel (Sue Taylor)

The original hotel pub was huge and occupied almost half of the ground floor. A friend of mine said his dad, who was a plumber, used to meet his pals at the Station Hotel for Friday drinking sessions in the 1970’s, and the family used to have Sunday lunch there on various occasions. Even then, my friend said, the Station Hotel was a ‘bit of a dive’.

For my visit to the hotel, I took two colleagues from Europe who thankfully were more interested in visiting this part of ‘the other’ Johannesburg rather than shopping at Sandton. We tried unsuccessfully to talk our way into the ground floor foyer to take photographs. Women and children were sitting on the front step of the hotel. They were fearful of anyone taking photographs. Instead, we had to make do with a peep from the door. It is difficult to imagine this foyer bustling with patrons, filled with the overwhelming smell of beer and the roar of male voices coming from the huge bar area on the right hand side of the ground floor.

From the hotel door, I could see that the enormous bar counter is still in place, but the bar area is barricaded with wire mesh gates, thick chains and huge padlocks. What was once the reception area with a wooden desk is now a gaping hole in the wall that doubles up as a small shop. The stairs to the upstairs rooms remain, but only as a concrete structure without handrails. Families live upstairs in the hotel now. People cook in their rooms and share bathrooms.

When no-one was looking, I scurried across the foyer and looked out the back door of the hotel - real squalor could be seen. Once a storage yard, perhaps with washing lines for hotel linen, the yard is now a cramped backyard settlement.

The Sixth Street Station Precinct

A large open area formed by Sixth Street leads towards the Denver Station entrance. Facing this open precinct are a number of very old shops, the Victorian-style Vickers Corner and the small 1930s block of flats, White City Mansions. The White City Mansions building (below), facing the Station Hotel, has also undergone various changes in use in recent times (from having a restaurant on ground floor in 2017, to this restaurant becoming residential units by 2022). The ventilation chimney from a restaurant kitchen remains to the right of the building. This style of building dates to the 1930s.

In 2017, patrons sit in the Sixth Street Square outside the Ranoto Restaurant in White City Mansions. (Google Maps)

In 2022, the restaurant has gone and ground floor shops are now residential units. The building has had a restorative coat of paint. (Sue Taylor)

The Sixth Street precinct next to the Denver Railway station is well designed, catering for the hotel and many small shops, with the shops (circa 1903) being older than the hotel (which is circa late 1930’s).

Small Victorian-era shops circa 1903, next to White City Mansions and facing the Denver Station Hotel across Sixth Street. (Google Maps)

Corner of the Station Hotel and set of very old shops facing onto Sixth Street, Denver station. Various hairdressing businesses operate from these shops. Children play soccer in this quiet area. (Google Maps)

Nothing much seems to change in Sixth Street, other the colour changes to Vickers Corner (see three images below). It appears as though Vickers Corner was named after Vickers Limited (1828–1927), a famous British engineering conglomerate. It is not clear what the association between the Sixth Street Vickers Corner building and Vickers company actually was. After the Boer War ended (1902) Vickers mining equipment from the USA and Canada was stored at Denver, Johannesburg and also in the suburb of Cleveland. There is also a Vickers Road (M19) which connects Denver and Main Reef Road (R29) to Southern Klipriviersberg Road (M19). Vickers went on to make machine guns and aeroplanes for World War I and II.

Vickers Corner in 2013 (Google Maps)

Vickers Corner in 2017 (Google Maps)

Side view of Vickers Corner (Sue Taylor)

The 2015 Denver Station MetroRail Crash

On the 28th of April 2015 at around 07h10, Business Express Train number 1602 failed to stop at a red signal and collided with the MetroPlus Express Train number 0600 at Denver Station. A man living next to the Denver train station described how he heard two trains colliding, Thulani Phakatse, 28, said “I heard the white train [Business Express] hooting and then there was a loud bang. I ran to the trains and helped some people come out. Some of them were crying” (News24 2015). Looking at the footage and photos of this crash, a medical rescue helicopter used the convenient large open precinct outside the Station Hotel to airlift the injured away. The cause of the accident was human error and not the theft of any railway infrastructure, meaning that the vandalism which has always existed had not yet crippled the MetroRail system.

The destruction of Denver railway station by looting

I can report that the Denver Station is in a sad state. It is closed for rail traffic, the electrical infrastructure has gone and only the walls of the ten or so platform waiting rooms remain. Up to 2020, the Denver railway station buildings and electrical rail infrastructure were intact (looking at Google Earth), but by 2021, the waiting room buildings no longer have roofs and are mere shells. The newish concrete perimeter wall along Berlein Street is broken and piles of household rubbish are dumped there. In fact, while I was taking photographs, a shopping packet of soiled diapers flew past me.

Uncollected rubbish piles up against the Denver station fence (Sue Taylor)

The north side passenger underpass leading to the platform is deeply flooded and filled with rubbish and old tyres. No-one could get through this swamp to the trains, even if there were trains running. By necessity, there are many informal foot paths from Berlein Street across the railway lines to Main Reef Road on the other side. The railways lines are rusted and over-grown with weeds.

Trains no longer run on this line (Sue Taylor)

The derelict Denver station platform (Sue Taylor)

Passenger waiting room in 2013. By 2022, the waiting room had been stripped down to the bare walls and the electrical infrastructure stolen. (Google Maps)

Passenger waiting room in 2017. The the same station electrical infrastructure was still in place, including the transformers on the mast next to the railway line and the blue palisade fence. Most of this infrastructure had been removed by 2022. (Google Maps)

As Johannesburg has grown over the decades, many old and unwanted buildings have been demolished, erased or replaced, making way for the new. Many old buildings have also just fallen down by themselves, or worse, burnt down. The Station Hotel and other buildings around Denver Station are holding up well, each being privately owned it seems and not hijacked, and thus looked after to some extent. While the Station Hotel could do with a facelift, the Vickers Corner and White City Mansions do get a coat of paint now and then. However, without regular structural maintenance they will be at risk. What is fascinating and valuable about these buildings is that, for now, one can still touch the past in these hardy remnants of early Johannesburg.

Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Her current interests encompass cities and urban greening, material culture (and what trash can tell us about society), degraded peripheries and researching the disintegration (and rehabilitation) of landscapes, railways and buildings. She has recently concluded a three year writing contract as a Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, QwaQwa, University of Free State (South Africa).

Sources

- De Jong R (2015) NZASM Structures of the Rand Tram. The Heritage Portal.

- News24 (2015). Witness describes Joburg train crash, screams

- Simelane BC (2021a). Sucking the marrow from the bones: Criminals return to finish off Gauteng railway stations April 2021.

- Simelane BC (2021b). Dead in our tracks: No trains, just more ruin as thieves and vandals strip Gauteng stations bare. Daily Maverick feature. September 2021.

- Simelane BC (2020c). Stripped bare: Looting till there is nothing left of Gauteng’s rail network. Daily Maverick feature. September 2020.

- Transnet Freight Rail (2021)

- Waters M (2020). PRASA loses more than R170m per year – Mike Waters. 15 June 2020.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.