Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

As you approach Hartbeespoort Dam on the R511, the road rises steeply over Saartjie’s Nek to reveal a spectacular view of the dam with the cliffs of the Magaliesberg behind. On a koppie to the right, a massive granite cross commemorates General Hendrik Schoeman and overlooks the grand panorama that he envisioned but never lived to see.

The memorial

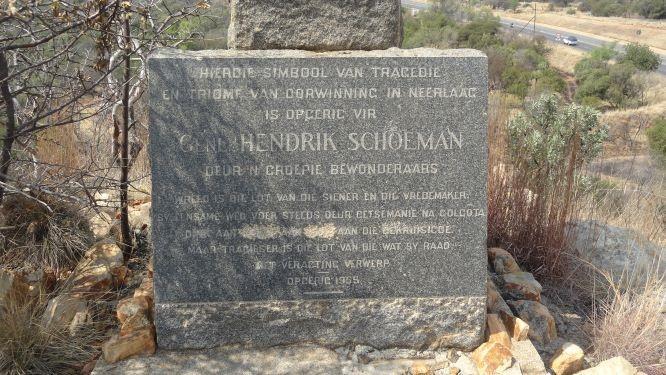

The 4m high cross is, however, more than a monument – it is an exculpation of Schoeman’s honour, erected by his son, Johan, 55 years after his father’s death. If you climb the stone path to the cross the strange epitaph hints at Hendrik Schoeman’s controversial life (translated from Afrikaans):

This symbol of tragedy

and triumph of victory in defeat

has been erected for

GENERAL HENDRIK SCHOEMAN

by a group of admirers.

Cruel is the fate of the prophet and peacemaker,

his lonely path leads through Gethsemane to Golgotha.

Think of Hess, of Petain, of the Crucified.

But even more tragic is the fate of those who reject his advice with contempt.

Erected 1955

Plinth for the memorial to Hendrik Schoeman

The names of Hess and Pétain were later chipped off the plinth. Rudolf Hess was Adolf Hitler’s Deputy Führer and secretly tried to negotiate peace with Britain during World War II. Marshal Philippe Pétain headed the puppet government in occupied France in collaboration with the Nazis. Associating Nazi sympathisers with Christ had not surprisingly caused offense.

What life lay behind this curious obituary?

Hendrik Schoeman was the son of Commandant General Stephanus Schoeman, who had led the pro-Potgieter Volksleger against the pro-Pretorius Staatsleger in the Boer Civil War of 1864. Hendrik fought alongside his father, but it was during the British annexation of the Transvaal from 1877 to 1880 that he really gained prominence.

War hero 1880-1881

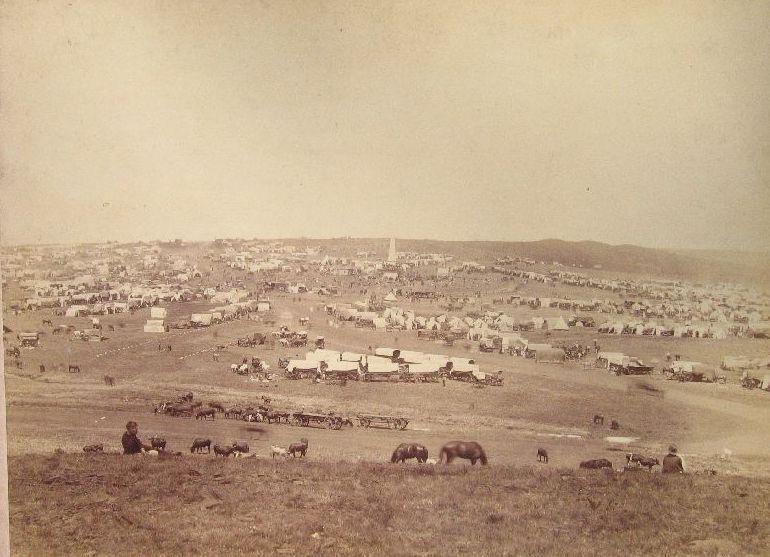

When the Boers declared the re-independence of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek at Paardekraal on 16 December 1880, it was Schoeman who carried the declaration to the British Governor, Sir Owen Lanyon, in Pretoria. Lanyon immediately sought ‘to restore the authority of Her Majesty’s Government and put down the insurrection wherever it may exist’. Thus began the First Anglo-Boer War.

Paardekraal Monument

The Boers routed a British column at Bronkhorstspruit and besieged British garrisons in seven Transvaal towns, including Pretoria. After the Boers lost a minor battle on the outskirts of Pretoria, Hendrik Schoeman was given command of the siege. He improved the efficiency of the blockade using a system of signals and mobile commandos that prevented the British garrison from another victory. When the Boers ultimately won the war at the Battle of Majuba the following February, Schoeman became one of the heroes of the war and was elected to the Volksraad and the Executive Council.

Majuba Cemetery

Agricultural visionary

Schoeman’s priorities, however, lay with his agricultural and business interests. He owned several farms including Hartebeestpoort in the fertile Crocodile River valley. He called it Schoemansrus and where the river winds through the Witwatersberg hills (now Meerhof), he built the largest dam in the country at the time, impounding a lake about 3km long. But he visualised something even bigger – a colossal irrigation scheme that would bring prosperity to the entire region. This grand scheme was thwarted by the outbreak of the South African War in October 1899 and only materialised 20 years after his death when the Union Government built the Hartbeespoort Dam on his farm.

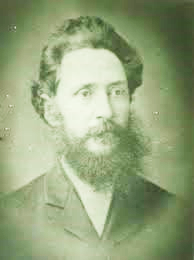

Hendrik Schoeman as a young man

Hartbeespoort Dam Wall (Wikipedia)

Humiliation in the South African War

The South African War not only destroyed Schoeman’s dream of a mighty dam, it was his personal nemesis. Given command of the Pretoria and Johannesburg Commandos defending the Orange River border, his generalship was over-cautious and incompetent. In February 1900 he was relegated to an administrative role in Bloemfontein from where, slighted and resentful, he returned to his farm in the Magaliesberg.

By early June 1900 the Boers were in full retreat and the British army bore down on Pretoria. A mounted column led by General French, encircled the town and, after a brief battle on the Kalkheuwel pass, the column crossed the Crocodile River at ‘Schoemansrus’, and Schoeman and French met face-to-face. Believing that the war was virtually over, Schoeman surrendered and signed an oath of neutrality.

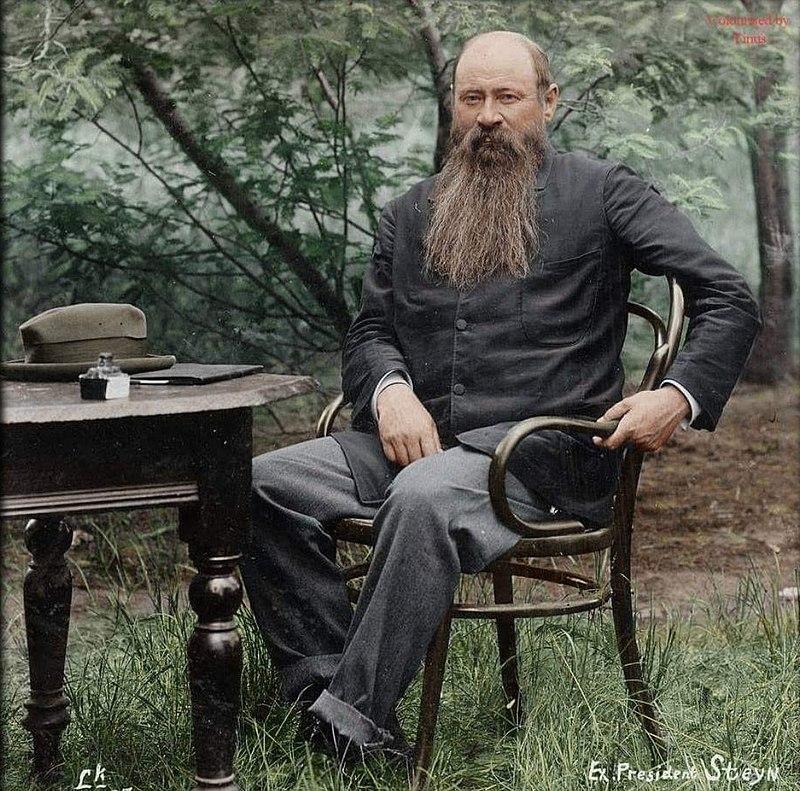

In Pretoria, Louis Botha and his senior generals had come to a similar conclusion and suggested to President Kruger that he should negotiate an end to the war. However, a stinging rebuke from President Steyn of the Orange Free State made them reverse their standpoint overnight. From that day, and for the following century, it became Afrikaner lore that those who fought to the bitter end (bittereinders) were the patriots while capitulation (hensop) bore the stain of treason. With notable hypocrisy, the Boer leaders condemned Schoeman for having the very views that they had held just days before.

President Steyn

The final months of Hendrik Schoeman

Schoeman celebrated his 60th birthday on 11 July 1900. On the same day, the revitalised Boers won three decisive victories at Silkaatsnek, Onderstepoort, and Dwarsvlei. Silkaatsnek was within sight of ‘Schoemansrus’ and Schoeman would almost certainly have watched the battle from his veranda. A few days later, Commandant Piet Coetzee, who held the pass, rode over to Schoeman’s house demanding that he (Schoeman) assist the Boer forces. When he refused, Coetzee arrested him and handed him over to the State Attorney, Jan Smuts. Smuts found no legal grounds for prosecution but sent Schoeman to serve under Louis Botha in the Eastern Transvaal.

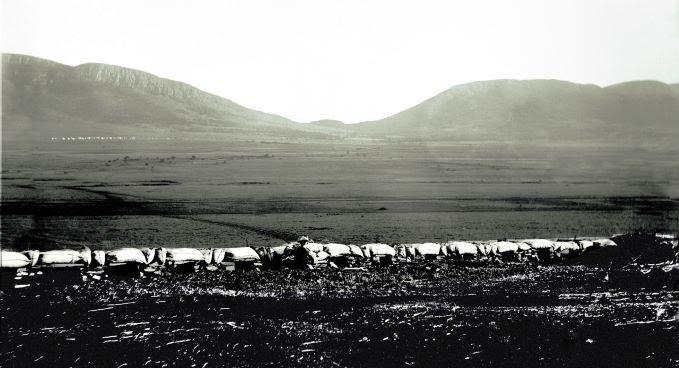

Silkaatsnek viewed from the British camp at Rietfontein in 1901. Schoeman’s burned-out house was slightly off-picture to the left (Kormorant)

Botha countermanded Smuts’s decision and charged Schoeman with treason. He was tried before a military court in Barberton but was acquitted on 11 September 1900. He returned to his farm, only to find that the British, believing that he had re-joined the Boer forces, had burned his house down.

Schoeman moved to Pretoria where he became increasingly concerned about the impact of Boer guerrilla resistance on Boer women and children. Other prominent Afrikaner civilians, including Meyer de Kock, Sammy Marks, the Rev. H.S. Bosman, Andries Cronje (brother of the former Chief Commandant of the Free State), were forming peace committees and sending emissaries to persuade bittereinders of the futility of fighting on. Schoeman aligned himself with their cause and persuaded Lord Roberts to allow him to visit De la Rey and try to persuade him to lay down his arms. Accompanied by Captain W.P. Anderson he set out to meet De la Rey near Rustenburg. On their way they were intercepted by one of General Beyers’s commandos and taken to Beyers’s headquarters at Warmbaths (Bela Bela).

Beyers refused to consider the letter Schoeman had prepared for De la Rey and sent him for trial at Nylstroom (Modimolle). Charged again with high treason, he contended that his concern had been solely for his country and the fate of its women and children. Commandant Lodi Krause, an eminent advocate, presided at the trial and found insufficient evidence of guilt. Schoeman was acquitted on 29 November, escaping a firing squad for the second time in three months. But bittereinder sentiment ran deep and the finer points of jurisprudence were often subordinate to vengeance. Despite the acquittal, many Boers were determined to see Schoeman punished. A re-trial was ordered and he remained in custody in Pietersburg (Polokwane).

This third trial, however, never took place. In April 1901 the British captured Pietersburg and Schoeman was free once more and returned to Pretoria. Just six weeks later, on 26 May, he was killed under what can only be described as an extraordinary circumstance. A lyddite shell he had apparently kept as a souvenir exploded in his living room, instantly killing him and his daughter and seriously injuring his wife and a guest who died soon afterwards from his injuries. Another guest was less seriously injured. He was the father of General Ben Viljoen, who, only weeks before, had ordered the execution of Meyer de Kock, who had gone on a similar peace mission to Belfast.

No formal enquiry into Schoeman’s death was ever conducted and it is officially recorded as an accident. Some believed that it had been “the judgement of the Almighty” but many questions feed a persistent theory that it had been premeditated and there were certainly many Boers who wished him dead.

Most accounts state that he either dropped a match or the embers of his pipe into the lyddite shell. Who witnessed that? Is it possible that an experienced soldier would be unaware of the danger of keeping an unexploded shell in the home and using it as an ashtray? And if so used, why had it not exploded previously? Is it mere coincidence that the only mildly injured witness to the explosion was the father of the man who had executed someone for exactly the same offence as Schoeman?

When Johan Schoeman erected the great granite cross 65 years ago, he compared his father’s actions with those of Hess and Pétain. They, too, had earned their country’s wrath by seeking peace with an enemy, and narrowly escaped execution. But they lived into old age, while Schoeman’s death remains an enigma.

About the author: Vincent Carruthers has written several books including The Magaliesberg (four editions), Cradle of Life (2019) and The Wildlife of Southern Africa (three editions). In 2006 he initiated the project to have the Magaliesberg region declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. He has received awards from various institutions including the University of the Witwatersrand Gold Medal in 2016 and the North West University Chancellor’s Medal in 2013. He has been CEO of WESSA, chairman of Birdlife South Africa and member of the North West Parks and Tourism Board. Currently retired from his management consultancy, he is enjoying writing for the Magaliesberg Association for Culture and Heritage.

Sources

- Grundlingh, A., The Dynamics of Treason: Boer Collaboration in the South African War of 1899-1902. Pretoria: Protea; 2006.

- Laband, J., The Transvaal Rebellion: The First Boer War, 1880-1881. Harlow etc.: Jongman Pearson; 2005.

- Lehmann, J., The First Boer War. London: Jonathan Cape; 1972.

- Spies, S.B., Methods of Barbarism? Roberts and Kitchener and Civilians in the Boer Republics: January 1900 – May 1902. Cape Town & Pretoria: Human & Rousseau; 1977.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.