Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in South Africa were times of turbulence and economic change. Settlers from the Cape explored deeper into the interior in pursuit of territory, adventure, and political and religious expansion. The process of opening frontiers led inevitably to ethnic confrontation and war. Among the many who influenced events in those stormy decades were at least eleven men who had similar surnames – Bain, Baines, or Baynes – and they are easily and frequently confused with one another in historical literature. That they lived and worked in the same region in approximately the same era, and in several instances followed similar careers, merely compounds the possibility of error.

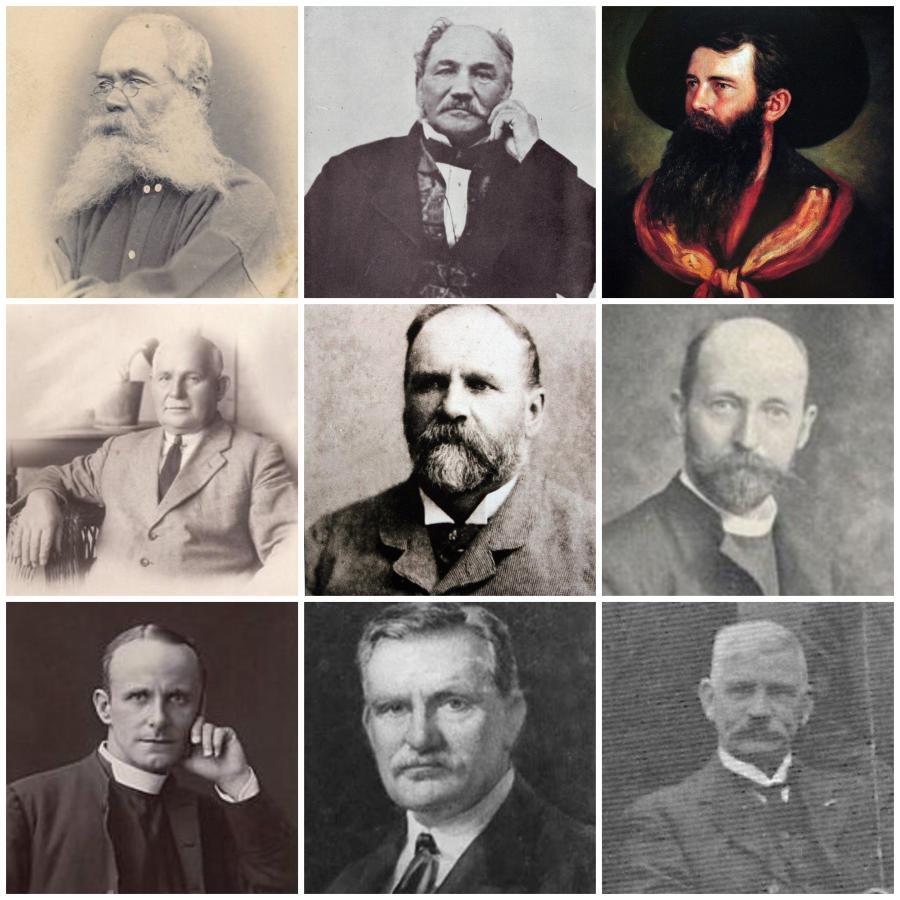

Thomas Baines, the explorer and artist, is the best known and he is often confused with Thomas Baynes, an engraver, artist and illustrator of books by other explorers. Andrew Geddes Bain and his son, another Thomas, were road engineers and sometimes muddled with Thomas the artist and Stewart Bain, another road builder around Harrismith. Baines, the artist, painted a hunting scene on Andrew Hudson Bain’s farm and they are sometimes assumed to be one and the same, although they never met. The Anglican Bishop of Natal, Arthur Hamilton Baynes, is often confused with his successor, Bishop Frederick Samuel Baines, because both were involved healing the schism in the Anglican church and in the founding of Michaelhouse. There are three others that are contenders for confusion: Sir Joseph Baynes of Baynesfield fame in KwaZulu-Natal, James Thompson Bain, the notorious trade unionist, and Donald Bain who came to prominence by exhibiting San Bushmen at the Johannesburg Empire Exhibition in 1936.

This article sets out to clarify the confusion and explain the different and significant roles that each of these eleven men played.

John Thomas Baines: 1820-1875. Artist and explorer

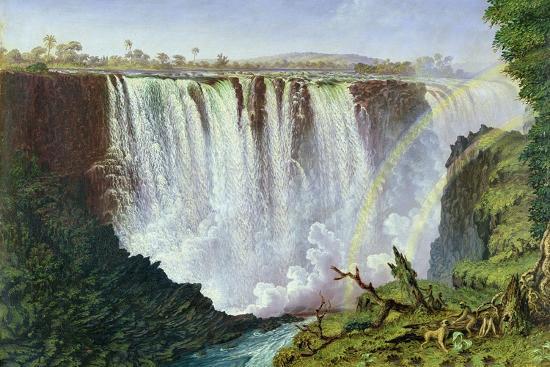

Thomas Baines – never referred to as John – is probably the best known of those discussed in this article and the one with whom the others are most often confused. Renowned for the enormous number of his paintings, drawings and sketches, he was a prolific diarist and observant traveller in southern Africa, the Zambezi area, what is now Namibia as well as in Australia. Much has been written about his life, some of which focuses on specific aspects of it.

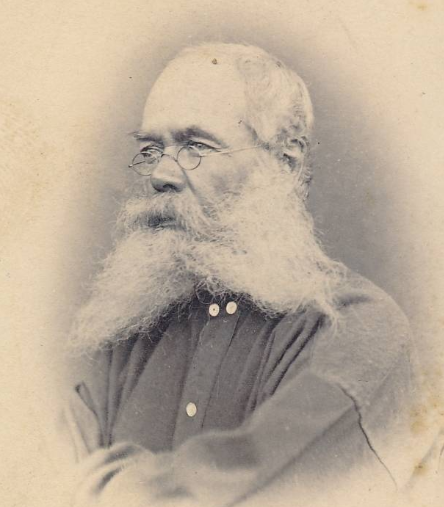

Self-portrait of Thomas Baines (William Fehr Collection via Wikipedia)

Baines was born to a relatively poor seafaring family in Kings Lynn, Norfolk. Showing some artistic ability – a talent shared by his brother Henry, who became a well-known local artist – Baines was apprenticed to a carriage decorator. The industrial revolution brought economic depression to the Norfolk area and Baines, then aged 21, sailed for the Cape of Good Hope. In Cape Town from 1842 to 1848 he worked as a commercial artist specialising in painting views of Table Bay and Table Mountain. In 1848 he decided to travel to Grahamstown, then an entrepôt for hunters and traders, and from where some exploratory travel seemed possible. However, this frontier community was not interested in purchasing art and for a time Baines was destitute. Unable even to afford a horse, he wandered on foot around the more remote eastern parts of the Cape Colony, accepting hospitality from rural Xhosa homesteads or sleeping in the open veld. In 1850 he was offered the chance of joining a hunting and trading expedition into the interior. For various reasons, this adventure did not go as planned and when he returned to the eastern Cape, for a year (1851) he was made official war artist attached to the forces of Colonel Henry Somerset in the Eighth Frontier War.

Back in England in 1852, he turned his southern African experience of amateur cartography to good effect. His work caught the attention of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), and this contact secured him a place as artist and storekeeper on an expedition led by Augustus Gregory to the Victoria River in north-west Australia from 1855-1857. Baines’s success in this venture led to the highlight of his career: the RGS appointed him to the team of the legendary David Livingstone to explore the navigability of the upper reaches of the Zambezi River. Regrettably, however, this was a disaster for Baines. In 1859 Livingstone dismissed him unfairly and, under a cloud, Baines retreated to Cape Town disgraced, humiliated, and once more without employment.

The opportunity to accompany James Chapman to hunt ivory in northern Namibia and around the Victoria Falls in 1861-1862, gave Baines another chance to travel and paint. He stayed in the area for the next two years illustrating the birds that explorer Charles John Andersson was studying. Baines received no pay for this, and once back in England in 1865 he had no funds and no prospect of returning to Africa. However, a couple of years later he learnt about a prospecting venture seeking gold and other minerals in today’s northern Botswana and Zimbabwe and, because of his central African experience, he was successful in being employed as its leader in 1868. Again, however, fortune eluded him, for the company that employed him ran out of funds and Baines died in poverty, of dysentery, in Durban in 1875 where he was buried.

Painting of Victoria Falls by Thomas Baines

Baynes, Thomas Mann, 1794-1876. Artist and engraver

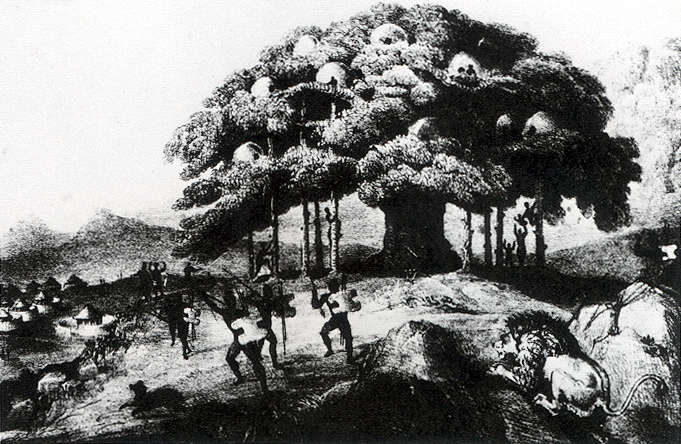

Thomas Mann Baynes was not an explorer himself and he never visited South Africa nor had any personal African connections. Born in London, he was a highly respected artist and lithographer who made his livelihood from art, engraving and printing. He frequently illustrated the work of other explorers, and he has been confused with Thomas Baines the artist discussed above. It is a lithographic engraving from a painting by Charles J. Hullmandel published in Andrew Steedman’s Wanderings and Adventures in the Interior of Africa (1835, Vol. 2, opp. p. 48) that connects Baynes to southern Africa and causes the muddle. The image is of the famous ‘inhabited tree,’ first published in Steedman’s book from an unpublished drawing by missionary Robert Moffat and descriptions from the hunter-traders Robert Scoon and William McLuckie. Steedman himself did not see it.

The Inhabited Tree

It is the tree (probably one of many), near Rustenburg, probably on the farm Bultfontein, in which starving BaKwena found safety by climbing into the branches to escape any prowling nocturnal predators after their homes and fields were destroyed by Mzilikazi’s incursions into the Magaliesberg region during the Difaqane of the 1820s. Most likely Ficus ingens, a local species of fig, the rather fanciful drawing was engraved as a lithograph –‘drawn on stone’ by Baynes – for Steedman’s book from Hullmandel’s painting. Both names appear beneath the image. The Steedman image has been widely reproduced and it is worth noting that the tree in Moffat’s own later book looks quite different. The engraver for that image was George Baxter who produced many colour illustrations for the London Missionary Society. However, the tree was never seen by, or drawn by, the more famous John Thomas Baines who would have been just 12 at the time of its first publication.

Bain, Andrew Geddes: 1797-1864. Explorer, road engineer and scientist

Andrew Geddes Bain looms large in South Africa’s early 19th century history and his versatile life is well recorded in numerous publications including his own journals. Despite the different spelling, it is remarkable how many authors attribute the work of Andrew Geddes Bain and his son to Thomas Baines, the artist. Born in Thurso in Scotland, Bain emigrated in 1816 with a military uncle who was stationed at the Cape. He married in 1818 and had 11 children, one of whom was Thomas Charles John Bain (see below). He settled in Graaff-Reinet and like many others became a trader and explorer. In 1825 he ventured with his friend and fellow trader John Burnet Biddulph to Kuruman, the mission station of Robert Moffat, and into Bechuanaland. They were the first White men to travel in this area. Bain did so again in 1834, this time with Griqua guides, who cost him his wagons and almost his life when they attempted to steal Ndebele cattle and were attacked by Mzilikazi’s men. A soldier during the eastern Cape Frontier Wars of 1833-1834, Bain also tried farming. An outspoken man he became a regular correspondent for the South African Commercial Advertiser often criticising his Dutch neighbours through his writings and satirical sketches some of which, like Kaatje Kekkelbek (Katie Gossip), were dramatised.

Andrew Bain (Past Masters)

He also embarked on roadbuilding, constructing the Ecca Pass near Makhanda (Grahamstown), and in this career, he excelled. He became Surveyor of military roads and then, in 1845, Engineering Inspector of the Cape Roads Board. Thereafter, he planned and constructed some of the most famous mountain passes: Michell's Pass, Bainskloof Pass in the Western Cape and many in the Eastern Cape. He became fascinated by geology. Bain read widely and befriended well-known scientific experts who confirmed his discoveries of many important fossils, some of which were exhibited in London and one of which was named after him. In 1852 Bain compiled the first geological map of South Africa which, in 1856, was published by the Geological Society of London and he was fêted by the geological and geographical luminaries in Britain.

Viewpoint over Michell's Pass (DRISA)

Oudenodon Baini Skull (Wikipedia)

Thomas Charles John Bain: 1830 –1893. Road engineer and scientist.

Thomas Bain followed his father into road construction and the two are almost invariably confused with one another. He also shares a first name with the famous artist creating further opportunities for mistaken identity.

Born in Graaff-Reinet, Thomas was the second son of the many children of Andrew Geddes Bain and his wife Maria von Backstrom and educated at home. At this time, the Cape Colony was developing, the interior was growing in economic importance, and the authorities set about improving transport routes between towns and districts. After serving as a volunteer in the War of the Axe in 1846, Thomas was apprenticed to his father in 1848 as Assistant Inspector of Roads and they worked together on Michell’s Pass and Bainskloof Pass. After completing the required examinations, Thomas was promoted to Roads Inspector for the western parts of the Cape Colony and he and his father collaborated until Andrew’s death in 1864.

Thomas Bain (Wikipedia)

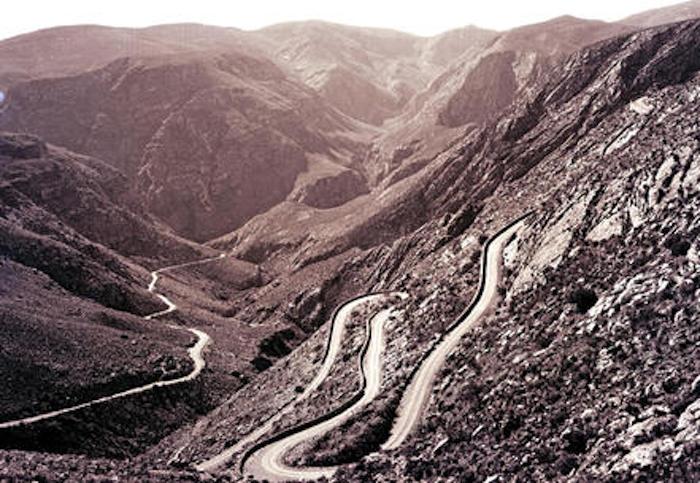

Bain was responsible for 24 mountain roads and passes, his first being Grey's Pass (Piekenierskloof), and includes the road between George and Knysna which took 15 years to complete. He became involved in the Millwood Goldfields, providing a geological plan of the area as part of the Gold Commission. There followed many other passes and roads, some very complicated, like those across the gorges of the Groot River, Bobbejaans River, Bloukrans River and Storms River. Thomas was employed by the railway department for a short spell, but returned to roads, in 1877 becoming an Associate of the Institute of Civil Engineers. His most complex achievement was the Swartberg Pass connecting Oudtshoorn with Prince Albert, completed between 1884 and 1887 and his last was Victoria Road between Cape Town and Camps Bay.

Swartberg Pass (DRISA)

In 1888 Bain was appointed Irrigation and Geological Surveyor where his experience and knowledge of geology was of great value. Like his father, Thomas took a serious interest in science. He collected and catalogued stone artefacts, excavated a cave near Knysna Heads, and devised a technique for copying rock paintings. He exhibited his findings in London and some of his collection is housed in the South African (now Iziko) Museum in Cape Town. At the request of the Cape Governor, Sir Henry Barkly, he collected plants, discovering four new species of Stapeliads, one of which, Hoodia bainii, was named after him (now Hoodia gordonii).

Andrew Hudson Bain: 1819-1894. Orange Free State landowner and surveyor

Andrew Hudson Bain was not related to the family of Andrew Geddes Bain, although this is often presumed, nor is he connected with Thomas Baines, the artist, besides the coincidence that the latter painted the famous hunting scene that took place on Andrew Bain’s farm.

Andrew Bain was born in Grenada, in the West Indies, the son of a plantation owner. He read classics at Edinburgh University before emigrating to the Cape in 1814 for health reasons. He settled in Colesberg, hunting in what is now the Free State and Lesotho. He joined the renowned big game hunter Henry H. Methuen and while in Kuruman met both Robert Moffat and David Livingstone. In the 1840s he became embroiled in the politics of Transorangia, raising a large commissariat of Griqua wagons to assist Major Henry Warden and Sir Harry Smith defeat the Voortrekkers under Andries Pretorius at the Battle of Boomplaats on 29 August 1848. Smith rewarded Bain with an enormous farm, Hartebeesthoek, near Bloemfontein.

Andrew Hudson Bain

Subsequently Bain acquired many other farms in the then Orange River Sovereignty. He surveyed Bloemfontein and drew the first plan of the town, and when the territory was handed back to the Boers as a republic in 1854, he remained there. For some years he managed his huge property with its menagerie at Bain’s Vlei (Hartebeesthoek) and maintained immense herds of wildlife. In August 1860 he was host to the second son of Queen Victoria, Prince Alfred – then aged 16 and on an official visit – together with Sir George Grey, the Cape Governor, and his party. Orchestrated by Bain, the Bain’s Vley/Vlei hunt on Hartebeesthoek lasted for just one day. A herd of about 30 000 wild animals was driven by local hunters, including many Barolong, towards the homestead where about 1000 were enthusiastically slaughtered by the visitors. The Barolong then continued the massacre thereafter. The event has been called ‘The Greatest Hunt in History’.

The Greatest Hunt in History (William Fehr Collection)

Apparently because of his advanced ideas about farming and the depression of the late 1860s Bain fell on hard times; he had to sell his farms and in 1869 was declared bankrupt. He tried his hand at the Kimberley diamond diggings but had no luck. He retired to the small town of Boshof where he later died.

The artist Thomas Baines visited the Orange River Sovereignty in 1850-1851, accompanying the trader Joseph McCabe, and heard about the Battle of Boomplaats. A few years later, while in Cape Town, he imaginatively reconstructed the Bain’s Vlei Great Hunt as one of several paintings commissioned to illustrate the 1861 commemorative publication on the Royal Visit.

Stewart Bain: 1854-1939: Mayor of Harrismith

Stewart Bain played a major role in the history of the town of Harrismith at the turn of the century. He and his brother James were road builders in the area, and were evidently pleased to be confused with, or associated with, Andrew Geddes Bain and his son Thomas Bain, who were by then well known. Born in Wick, Scotland, Stewart and James landed in Durban in 1878 and began building roads and railway bridges. They then decided to settle in Harrismith where Stewart bought the Railway Hotel renaming it The Royal.

Founded in 1849, Harrismith moved to its present location in 1850, and was named for Sir Harry Smith, Governor of the Cape Colony from 1847 to 1852. Being close to the Natal border, Harrismith became a busy transport hub for travelling to and from the Kimberley diamond fields, becoming second in size only to Bloemfontein, the Orange Free State capital. But access was often difficult until bridges were constructed over the Wilge River to allow traffic to flow in times of flooding. According to a family online record – the only evidence available – Stewart Bain was involved in this work.

Stewart Bain

Bain became Mayor of Harrismith, a position he is said to have occupied for a number of years earning him the sobriquet of ‘The Grand Old Man of Harrismith’. The imposing red-brick English Renaissance styled Town Hall was planned and built during the period that he was Mayor and was dubbed ‘Bain’s Folly’. When Stewart Bain died in September 1939, he was given an impressively large funeral procession through the streets of Harrismith and the Town Hall is now a Provincial Heritage Site.

Harrismith Town Hall

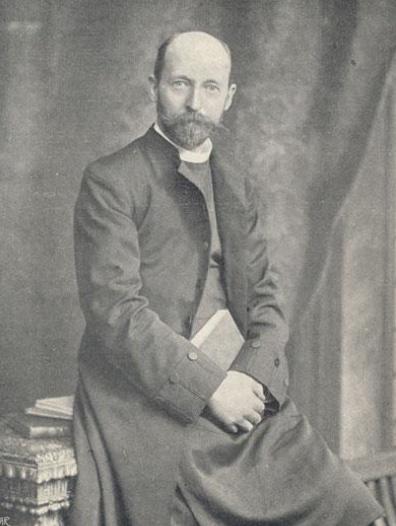

Reverend Arthur Hamilton Baynes: 1854-1942. Bishop of Natal

Two successive Anglican Bishops of Natal are often confused with one another because they shared a common surname, albeit differently spelled, and they were both closely involved in the founding of Michaelhouse.

Arthur Hamilton Baynes was born in Lewisham, Kent, educated at Oriel College, Oxford, and ordained in 1882. He served in various English parishes before being appointed Domestic Chaplain to Dr E.W. Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury, a position he held from 1888-1892. Baynes was consecrated Bishop of Natal in 1893, his main task being to heal the rift in the Anglican Church that had been created by the highly controversial and liberal views – theological and political – of Bishop John William Colenso, Bishop of Natal from 1854. Despite what were regarded by some as his heretical views, Colenso remained in office until his death in 1883. William K. Macrorie became a rival Bishop for those opposed to Colenso and each had his own following. After Colenso’s death and Macrorie’s resignation, the time for reconciliation seemed appropriate. Benson had tried, but failed, to heal the breach from London, but he did manage to have Baynes accepted as Bishop of Natal by both factions for a period of seven years. By the time Baynes left Natal in 1901, his energy and tact had brought most of the dissident congregations back into the Anglican Church of Southern Africa (known until 2006 as the Church of the Province of Southern Africa).

Bishop Arthur Hamilton Baynes

However, his work was hampered by the upheavals of the Jameson Raid (1895-1896) and the South African War (1899-1902), during which he acted as an honorary army chaplain. He returned to England and ended his career as provost of Birmingham Cathedral. Baynes was married twice: his first wife, Cecilia, was the daughter of the Reverend J. Crompton of Pinetown.

Bishop Baynes and other leading Anglicans had recognised the need for a church school and a committee was established by Baynes to find a location and raise funding for this purpose. Baynes himself made a major initial donation of £100. He had been accompanied out to the colony by his Domestic Chaplain, James Cameron Todd, and it was Todd who, with the encouragement of the Bishop, became the founding Rector of Michaelhouse as a Diocesan College in 1896.

Another priest had come out to Natal with Baynes and Todd. This was Frederick Samuel Baines who was to succeed Baynes as Bishop of Natal and who also played a large role in the early years of Michaelhouse.

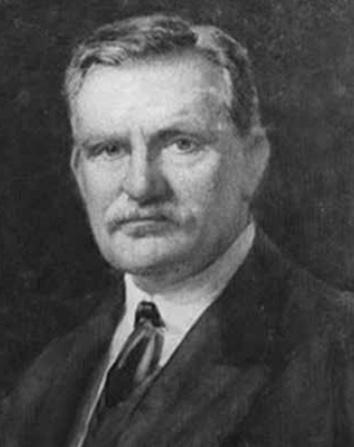

Reverend Frederick Samuel Baines: 1858-1939. Bishop of Natal

Rather confusingly, the successor to Bishop Baynes in Natal was Bishop Baines, who held this position from 1901 to 1928. Baines was born in 1858 in Steyning, Sussex, educated at Winchester and Oxford and was ordained in 1882. He served in a number of parishes in England before coming to Natal in 1893 with Arthur Hamilton Baynes and his (Bayne’s) Domestic Chaplain, James Cameron Todd. After Baynes returned to England in 1901, Baines became Bishop of Natal in his place.

Bishop Frederick Samuel Baines

When peace returned after the South African War, reconstruction and development began anew. While Baynes had had some success in dealing with the schism within the Anglican community, it was soon clear that divisions still persisted. Baines sought to continue the rapprochement but created more antagonism than reconciliation and he was not able to bring the Church of England in Natal under his control, nor many of the properties it still owned from the Colenso era.

While he was Bishop of Natal, a position that he held for more than 25 years, Baines turned his attention to expanding the missionary and educational work of the church among the Zulu and Indian communities. He was also instrumental in the education of boys and became deeply involved in the early years of establishing Michaelhouse and Baines House, one of the current ten Houses at Michaelhouse, is named after him. In addition, Baines was keen to create a preparatory, or feeder, school for scholars intending to go to Michaelhouse. In 1912 Baines bought an old house named Blenheim on Town Hill in Pietermaritzburg for £1450; it was renovated, and grounds were acquired. The new preparatory school was named Cordwalles after the school at which his nephew had been educated.

Baines, who never married, resigned in 1928 and returned to his birthplace.

Cordwalles School (Wikipedia)

Sir Joseph Baynes: 1842-1925. Natal farmer and politician

Joseph Baynes C.M.G.is less frequently confused with those similar surnames but, because of his prominence in the affairs of Natal where some of the others were active, he is included in this article to preclude any possible mistake. He was born near Settle in Yorkshire and accompanied his father, Richard Baynes, who arrived as a settler in Natal in 1850. Joseph had little education but he was intelligent and something of a visionary. In 1868, he took over his father’s farm, Nels Rust, transforming it into an agricultural showplace. He bought up neighbouring farms until he owned about 10 000 ha. He experimented with various crops and different cattle breeds, popularising Frieslands in Natal. Working with veterinarian Herbert Watkins-Pitchford, he researched East Coast fever and was the first local farmer to dip his cattle against this disease. Baynes contributed substantially to the establishment of the dairy industry in Natal, utilizing electricity and other modern technical innovations. He also supported the development of agricultural organisations in creating markets for products like butter and bacon. A protectionist, he was one of those responsible for the Customs Convention of Natal, the Orange Free State, and the Cape Colony.

Sir Joseph Baynes

Although not an eager politician, Baynes joined the Natal Legislative Assembly as the representative for Ixopo in 1893 when Natal was granted responsible government. After the South African War, he served as Natal Minister of Lands and Works and was made C.M.G. in 1902. Baynes had many interests – social welfare, mining, and the Salvation Army. He served on the Indian Immigration Board, and although he had a reputation for racial conservatism there is some evidence that his views shifted over his lifetime.

When Baynes died childless in 1925, he left Baynesfield, his large estate, in trust for South Africans. It is a working farm and Baynes House, the gracious home he built for his second wife, contains some original furniture and is regularly visited by schools and other tour groups.

Baynesfield Estate

James Thompson Bain:1860-1919. Socialist and labour leader

James Thomson Bain was quite different from any of the others with similar names. Born into poverty in Dundee, Scotland, and deeply influenced by the emerging Labour and Socialist/Syndicalist movements in Britain, Bain is a little-known figure in South African history but an important and fascinating one. As a young man he joined the British army, serving in Pretoria during the Annexation of the Transvaal in 1878, in the Anglo-Zulu War in 1879, and in India from 1880 to 1882. He then left the military, settled back in Scotland, and trained as a fitter. During that time, he became familiar with Socialist ideas and ideology, reading widely and coming in contact with leading European Socialists like Thomas Carlyle, William Morris and others, joining the Scottish Land and Labour League and taking an activist part in the movement.

James Thompson Bain

In 1890 Bain immigrated to Cape Town and soon had a reputation as a zealous Socialist. He moved to Kimberley and from there to Johannesburg. He was active in the Labour Union in 1892 and before long he was a leading figure. He was a founder of the Johannesburg Trades Council in 1893 and editor of the newspaper Johannesburg Witness in 1899. During the South African War, resolutely anti-British and anti-capitalist, Bain fought on the side of the Boers. When Johannesburg fell to the British in July 1900, he was captured and faced a charge of treason, but was eventually accepted as a prisoner-of-war and sent to Diyatalawa camp in Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Released in 1903, he returned to Johannesburg as an anti-establishment agitator. He became President of the Transvaal Independent Labour Party in 1906 and in 1913 he was working full-time with the Trade Union Federation.

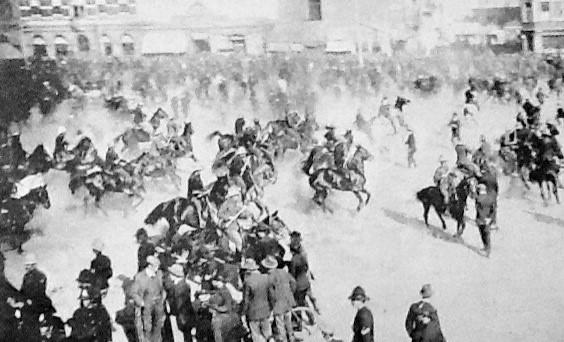

June 1913 is etched in Johannesburg’s history. A long strike by White miners and railway workers for trade union recognition, higher pay, and better working conditions escalated into violence and the declaration of martial law. Eventually, after aerial bombing of the strikers and several fatalities, an agreement was reached between the unions and the state. Bain was arrested but released on bail and then secretly and illegally – because he was a naturalised citizen – he was deported to Britain with some of the other strike leaders. They soon returned to Johannesburg, but the First World War intervened and the labour movement was unable to regain its strength. Early in October 1919 Bain became ill and was admitted to the Johannesburg General Hospital where he died later that month.

Police Charge on the Market Square in 1913

Donald Bain: 1902-1948. Campaigner for the rights of the Kalahari ǂKhomani San/Bushman

The last of the Bains to be considered in this article is Donald Bain who rose to prominence briefly when he brought a group of about 70 Kalahari ǂKhomani San (Bushman) to the 1936 Empire Exhibition in Johannesburg. The Exhibition, according to contemporaries, showed Johannesburg to be ‘on the crest of a prosperity wave’ when Milner Park (now the West Campus of the University of the Witwatersrand, Wits) was transformed into a showcase of South African ‘progress’ with the city at its core.

Donald Bain

Although the display of living people is today regarded as appalling, Bain had no wish to humiliate or commodify the people he brought to Johannesburg, and he made no money from the exhibit. He had been fighting for a Bushman Reserve for more than 20 years and regarded the San as a ‘vanishing race’, one of the world’s most ancient. His purpose in having them at the Empire Exhibition was to bring their plight to public notice. He delivered lectures about them to onlookers while a group of about a dozen at any time, sang, danced, explained their bodily decoration, and made ‘muthi’. Bain sold a pamphlet to raise funds for a Bushman Reserve which he envisaged as being along the lines of the many ‘Native’ reserves in existence at the time.

Bain was unsuccessful in his endeavour. Support for the reserve depended on how the exhibition was received; some visitors regarded Bain as a showman and opposed his actions, while others noted his noble motives, but with time the exhibition and the San faded into memory. Despite newspaper advertisements and other publicity, Bain raised only £60 of the £30 000 he sought.

Some of the group of Khomani San (Bushman) brought to the 1936 Empire Exhibition in Johannesburg by Donald Bain

Donald Bain was the son of John Miller Bain (1868-1956) who had been born in Wick in Scotland and who is recorded as a cabinet maker or carpenter in Cape Town. R.J. Gordon states that Bain was a great-grandson of Andrew Geddes Bain and that much was made of this connection in 1936. However, the relationship with either of the two sons of A.G. Bain – Robert Alexander (1828-1888) or Thomas Charles John (1830-1893) – cannot be verified.

Bain hunted regularly in the northern Cape in the 1930s and Raymond Dart, Professor of Anatomy at Wits, accompanied him for a month to select ‘true Bushmen’ for the exhibition, describing him as a ’colourful hunter’. Bain’s hunting camp was at Twee Rivieren which lay within the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park that had been established in 1931. The politics around the founding of this national park were complicated. Numerous San Bushman groups lived and hunted in the protected area and the question was whether the government would allow them to remain. The debate about their access to, and ownership of, this region continues to this day.

Click here to download a word version of this article which includes references.

Jane Carruthers is Professor Emeritus at the University of South Africa, elected Fellow of the Royal Society of South Africa and Member of the Academy of Science of South Africa. She has been awarded many international visiting research Fellowships, including at Cambridge University, the Australian National University and others. She is a former President of the International Consortium of Environmental History Organizations, the Southern African Historical Society, Chair of the Academic Board of the Rachel Carson Centre Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, Editor-in-Chief of the South African Journal of Science, and recipient of the Distinguished Scholar Award from the American Society for Environmental History. She pioneered the discipline of environmental history in South Africa and her book, The Kruger National Park: A Social and Political History (1995) has become a standard reference worldwide. Her research interests are broad, and include environment history, national parks, the history of science, land reform, colonial art, ad comparative Australian-South African history. She is the author of numerous books, as well as many book chapters and articles in scholarly journals.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.