Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Parliament Square is often viewed as a sanctuary of British constitutional history. Framed by the Palace of Westminster and the Abbey, it serves as a visual record of the 20th century’s geopolitical shifts.

Looking across Parliament Square (The Heritage Portal)

However, for a visitor with a South African perspective, the square offers a more specific narrative. Standing among these twelve statues (not all 20th century), one realises that the careers and philosophies of several of these figures were fundamentally shaped by their experiences in Southern Africa. This survey explores the historical links between Parliament Square and South Africa, reflecting on how the region served as a catalyst for some of the century’s most influential leaders.

Jan Christian Smuts (1870–1950)

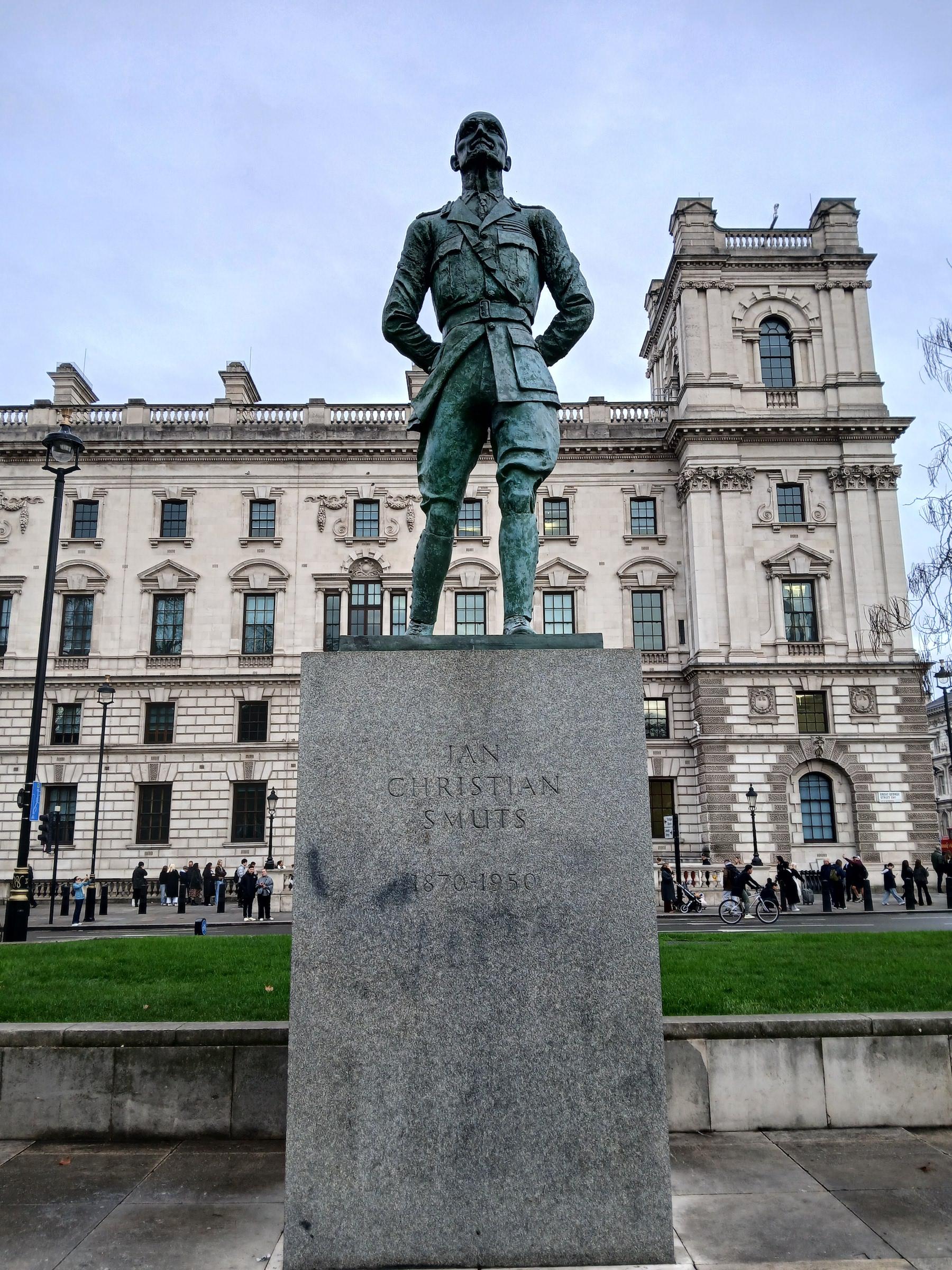

The statue of Smuts, positioned on the north side of the square, represents the most direct link to South Africa. Sculpted by Sir Jacob Epstein and unveiled on November 7, 1956, it depicts the Field Marshal in his military uniform, leaning forward in a characteristic stride. Smuts’s presence in the square reflects his dual identity as a South African Prime Minister and a British Field Marshal. He remains a central figure in international history due to his work in the Imperial War Cabinet and his role in the formation of both the League of Nations and the United Nations.

Jan Smuts Statue on Parliament Square (The Heritage Portal)

Winston Churchill was a primary advocate for this memorial, which stands on a pedestal made of South African granite. While Smuts is celebrated in many countries as a cosmopolitan statesman, his legacy remains complex. His support for segregationist policies at home provided part of the framework that Apartheid leaders would later entrench.

Critics at the time likened Smuts’s pose to that of an ice skater

Nelson Mandela (1918–2013)

In the southwest corner stands the figure of Nelson Mandela. The nine-foot bronze by Ian Walters was unveiled in August 2007 by Prime Minister Gordon Brown, with Mandela himself in attendance. The statue marks the transition of South Africa from a pariah state to a celebrated democracy, standing as a physical counterpoint to the statues of the colonial era. Unlike the other figures in the square, Mandela is positioned on a notably low plinth, a design choice intended to reflect accessibility and his connection to the people.

Mandela Statue on a low plinth (The Heritage Portal)

The path to this unveiling was marked by a decade-long debate over its location. The original campaign sought a place in Trafalgar Square (the site of decades of anti-apartheid vigils). The compromise to move the statue to Parliament Square was a significant shift, elevating Mandela from a figure of protest to a global statesman.

Another view of the Mandela statue (The Heritage Portal)

There is a powerful historical irony connecting these two figures. Mandela recalled walking through Parliament Square with his friend and colleague Oliver Tambo in 1962. At the time, they were in London to seek support for the struggle. As they passed the statue of Jan Smuts, Mandela joked to Tambo that perhaps one day, a statue of a Black South African leader would stand in the square as well.

The "dialogue" between the Smuts and Mandela statues serves as a narrative arc for South Africa. One represents the country’s colonial ties, while the other represents its transformation into a constitutional democracy.

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948)

Unveiled in March 2015, the statue of Gandhi by Philip Jackson is based on a 1931 photograph of Gandhi outside 10 Downing Street. Although Gandhi is celebrated as the father of the Indian nation, his political identity was forged during his time in South Africa from 1893 to 1914. It was in the Transvaal and Natal that he developed Satyagraha, or non-violent resistance, in response to racial discrimination. It was through direct confrontation with racial laws—being thrown off a train in Pietermaritzburg for refusing to leave a first-class compartment, organising mass protests against pass laws, and enduring imprisonment—that Gandhi refined his philosophy of resistance. The techniques he developed in South Africa became the blueprint for India's independence movement and influenced civil rights struggles worldwide.

Statue of Gandhi in Parliament Square (The Heritage Portal)

Gandhi outside 10 Downing Street (Wikipedia)

The statue was funded by the Gandhi Statue Memorial Trust. Its placement is historically significant as it stands near Churchill, who was famously critical of Gandhi’s methods.

Winston Churchill (1874–1965)

Arguably, the most prominent statue in the square is the bronze of Winston Churchill, created by Ivor Roberts-Jones and unveiled in 1973. Churchill’s political rise began in South Africa. As a young war correspondent during the South African War, he was captured by Boer forces on November 15, 1899. His subsequent escape from a prison in Pretoria and his journey to Lourenço Marques made him a household name in Britain and provided the momentum for his entry into Parliament.

Young Churchill (Imperial War Museum)

Churchill’s relationship with Jan Smuts is one of the more durable political friendships of the era. Despite being on opposite sides during the South African War, they became close allies during both World Wars. Churchill frequently sought Smuts’s counsel on matters of global strategy, and their correspondence reveals a high degree of mutual intellectual respect that bridged the gap between the British Empire and the developing South African state.

Churchill Statue on Parliament Square (Heritage Portal)

Millicent Fawcett (1847–1929)

The square’s first statue of a woman, by Gillian Wearing, was unveiled in 2018. While primarily honoured for her leadership in the suffrage movement, Fawcett has a notable South African connection through her humanitarian work. During the South African War, Fawcett was appointed to lead the "Ladies' Commission" to investigate British-run concentration camps in 1901.

While her appointment was seen as a strategic move to counter the more radical reports of Emily Hobhouse, Fawcett’s findings nonetheless confirmed the high mortality rates and poor sanitation in the camps. Her report led to administrative changes that improved conditions, though the commission notably did not address the separate camps holding Black Africans. Her presence in the square acknowledges a figure who used her political influence to address grievances within the South African context, albeit through the specific lens of the time.

Millicent Fawcett Statue (Heritage Portal)

Conclusion

For the South African visitor, Parliament Square functions as a gallery of shared history. The square demonstrates that South Africa was not merely a peripheral territory, but a stage where 20th-century concepts of human rights, internationalism, and reconciliation were tested. Whether through the diplomacy of Smuts, the activism of Gandhi, or the resistance of Mandela, the influence of the South African experience remains visible in the center of British power.

James Ball is the founder and editor of The Heritage Portal

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.