Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The concept of a ‘Lido’ is not familiar to most contemporary South Africans, least of all the idea of one situated in Johannesburg. However, in the 1930s the city might have had its own Lido – right in the heart of what is now Sandton!

The word ‘lido’ is Italian, with its origins in the Latin ‘litus’, meaning ‘a beach’ or ‘shore’ (giving us the English word ’littoral’). The world-renowned Lido is the Lido di Venezia – a barrier island off Venice with a sandy beach that has been a bathing resort and a place of entertainment for a very long time. The annual Venice Film Festival is held there. In the 19th century, the Venetian Lido was a fashionable holiday destination for the rich, particularly from England and the rest of Europe, and apparently its attractions and sophistication were the envy of seaside resorts elsewhere.

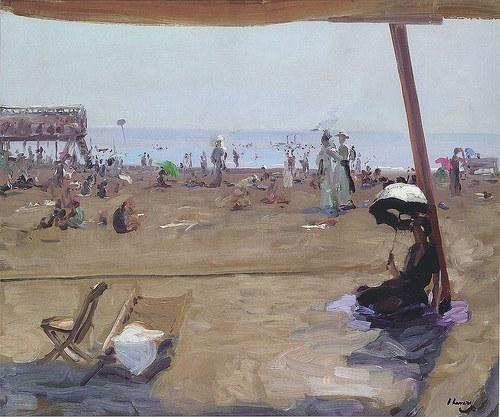

Bathing in the Venice Lido by John Lavery

So popular was the idea of a Lido, the very word resonating with notions of luxury, relaxation, sunshine, and wealth, that Lidos sprang up all over Europe in the late-19th century, particularly in England – and not only at the seaside. Before the age of cheap and easy travel, urbanites who craved a beach experience could find one inland. These were especially constructed areas with all the accoutrements of a seaside vacation – a fashionable destination, a swim in cold water in a large swimming pool, the atmosphere of bathing boxes, children’s entertainment, hotel accommodation, fountains playing, and ice-creams and cocktails to hand. The internet explains that the word Lido was first used in English in 1860 to denote a ‘fashionable beach resort’, despite the fact that many Lidos were not located close to the sea.

According to Country Life:

Ah the glorious British Lido! Is there anything more refreshing, particularly in a hot city suburb, than the cold splash of an unheated outdoor 1930s swimming pool? Well, possibly eating an ice cream while you're still cool from the water. In terms of atmosphere, lidos are as close to the beach as you can get without actually going to the beach. Children run around, adults sunbathe around the perimeter, groups of young people dangle their feet in the water. We actually have those strait-laced Victorians to thank for introducing lido culture to the UK, although it wasn't really until the 1930s that the golden age of the lido began, as swimming for pleasure and socialising at lidos peaked in popularity.

Saltdean Lido - A-Derelict 1930 Lido East Sussex (Scott Ramsey Photography)

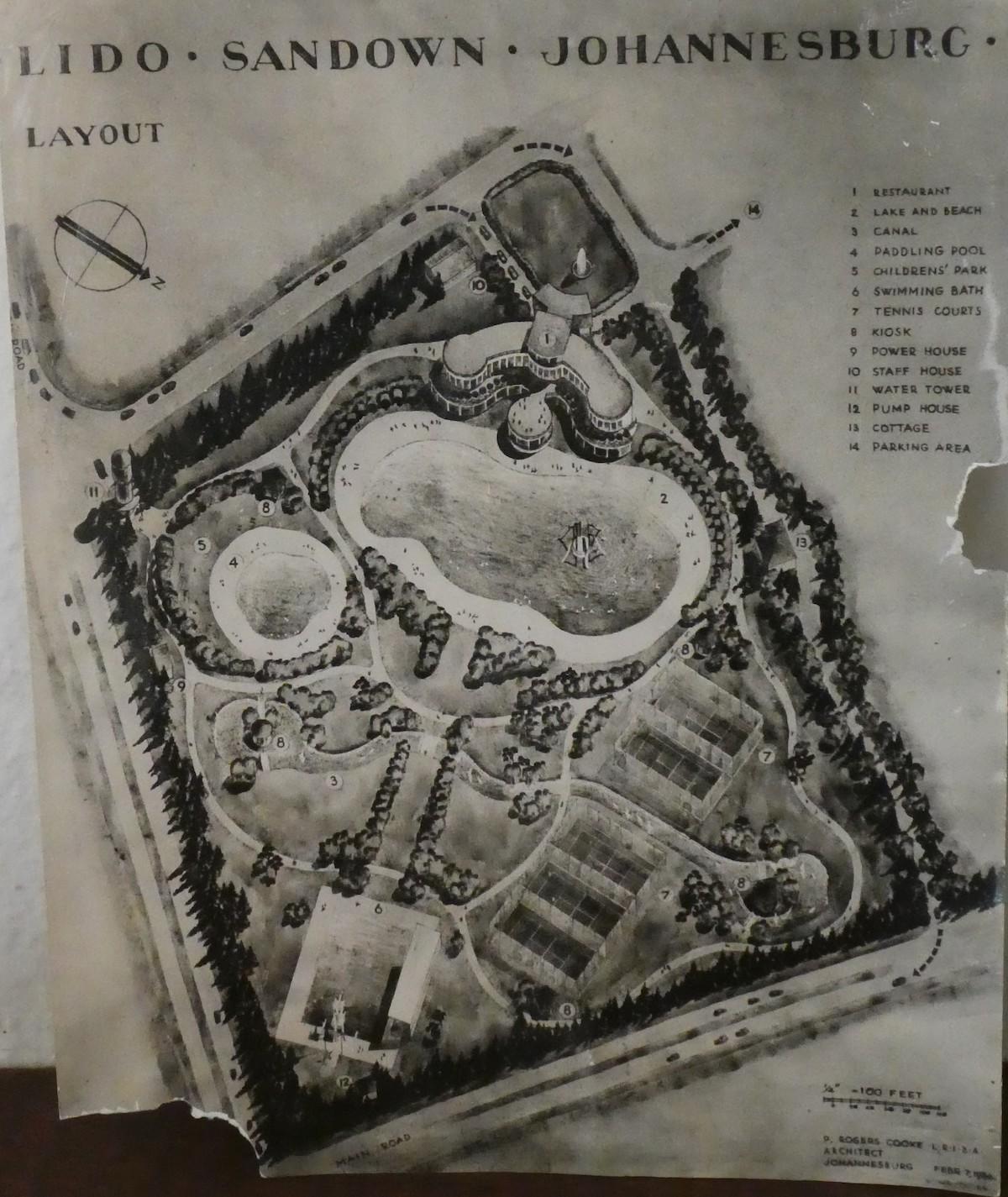

Never in the rear-guard of fashion, in 1936 there was a plan to construct a Lido in Sandown. The explanation above serves to introduce Johannesburg’s Lido, a little-known project that, unlike many Lidos elsewhere, did not take off and provide a popular recreational facility for the city. But that was not without a good try! Our local Lido was to be located on the corner of Rivonia Road and West Street where the old Sandton civic buildings and library are now situated.

Location of Sandton Library (The Heritage Portal)

Demolition of the Civic Centre in 2015 (702)

In 1975, Town Councillor Reuben Sive (1913-1994), then a member of the newly formed Sandton Historical Association, was given a copy of a ‘Prospectus of South African Lidos Limited’, together with a photograph of the model of the proposed Lido by the family of Councillor G.A.A. Bosman, a long-standing member of the Sandown Local Area Committee (a component of the town of Sandton) and one of the first Town Councillors.

Front cover of Sandown Lido Prospectus

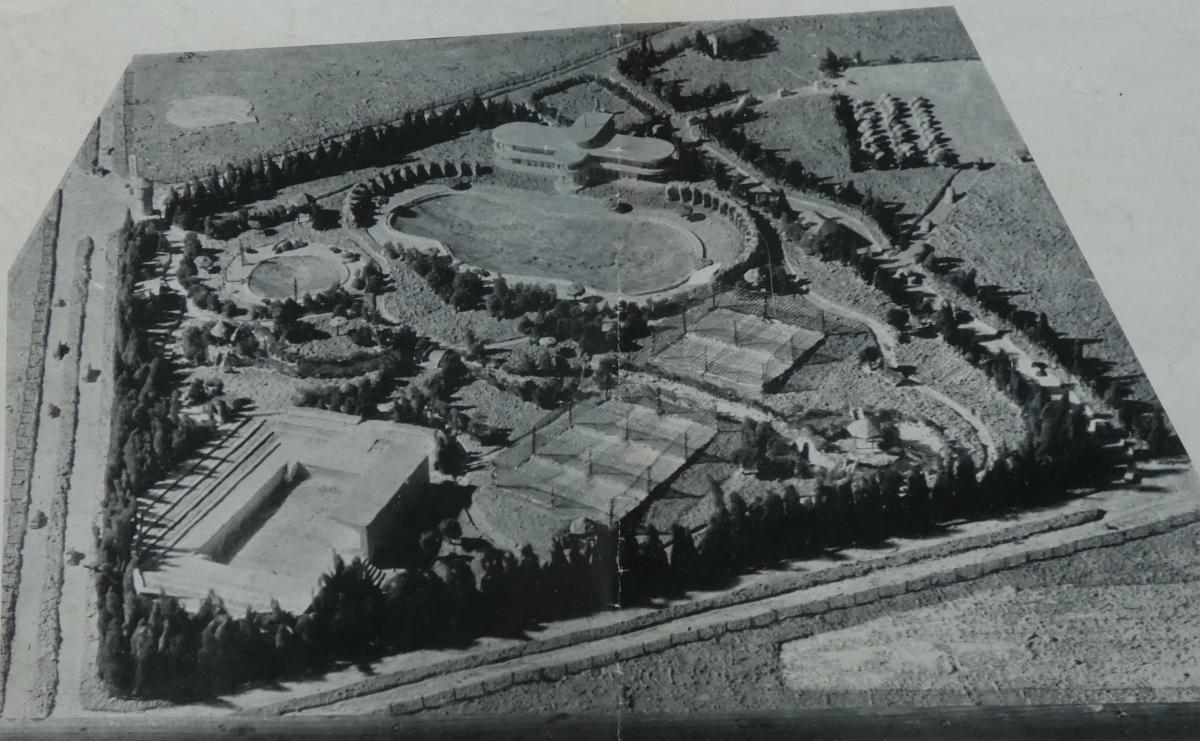

The Lido Model

The key plan that Sive handed over to the Association is detailed – showing exactly how far from, or how close to, central Johannesburg the Lido was to be. At the time, 1936, the Sandton area abounded with resorts and tea gardens. One of them was Pilkyvale – near Benmore Gardens and only demolished in the 1980s; it was shown on the Lido plan. Rattray’s Dam in Craighall on the Braamfontein Spruit was another weekend destination for Johannesburg’s wealthy, as was the property belonging to Sir Thomas Cullinan, named Rocklands, in what is now Woodmead, that was a fashionable tea garden run by Winifred Berrington, a sister of Lady Cullinan.

Pilkyvale

Craighall Lake

The 1936 Lido in Sandown, however, was to be far more ambitious and grander than any mere tea garden or farm dam. It was to be laid out as an enormous formal garden, surrounded by trees, with well-sited tree-lined paths and walks and appropriate interesting places, named ‘kiosks’ on the plan, to stop and chat or merely to sit and relax. There were to be a lake and beach, a canal flowing through the property, a children’s paddling pool and park, a very large swimming pool and diving board, and an elaborate restaurant and rotunda facing the ‘beach’. Because most of the surrounding landscape was farmland or large smallholdings, the Lido would offer what are now called ‘staycations’ and an escape from the bustling and burgeoning 1930s city of Johannesburg. It was to be a magnificent edifice to add value to the city and, given the architectural period and the philosophy of its designers, potentially an Art Deco treasure as some Lidos of that time have become in today’s Britain.

Maximising their exposure to what was exciting and trendy in recreation and entertainment in Europe and the United States in the 1930s, the designers and developer devised a Lido plan even bolder in its way than Sandton City was to be some forty years later when that centre came into being in the early 1970s. Any property development is a gamble, and whereas Sandton City took off, with consequences that are today well known, Sandown’s Lido did not, and even its possible existence has been forgotten. Instead of an early version of Sol Kerzner’s Sun City and an escape from urban life, the fate of this part of Sandton (founded in 1969) was to become yet another unimaginative and over-crowded CBD, itself a large and densely populated city.

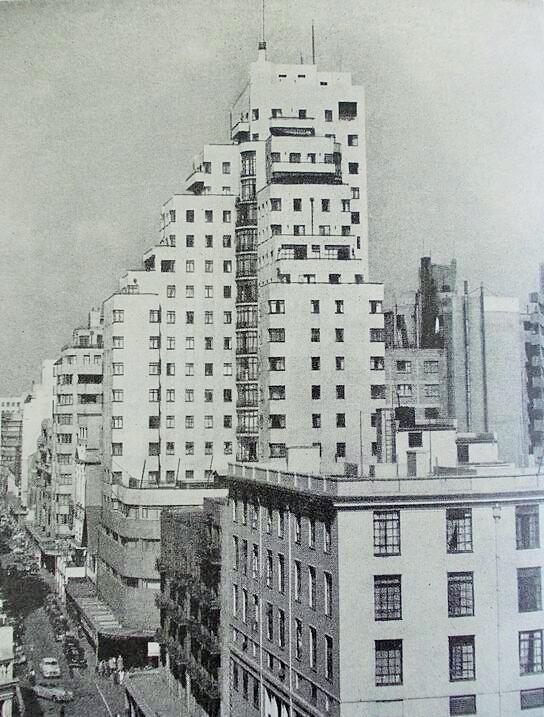

Sandton CBD (The Heritage Portal)

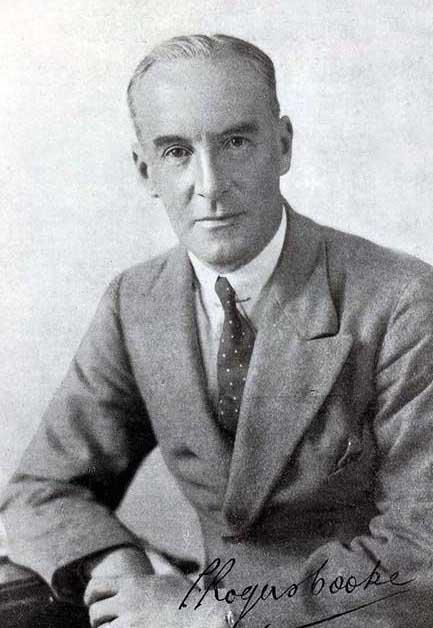

The Lido’s planners could not have had better credentials. The architect responsible for the Sandown Lido concept and the drawings in the prospectus was Percy Rogers Cooke. An extremely versatile architect, he was born in England in 1880 and trained as an engineer at the Crystal Palace School of Engineering. After the end of the South African War with all four colonies under British control, he emigrated to Johannesburg. From 1903 to 1910 he was employed in the department of Johannesburg’s Town Engineer as an engineering assistant, and he then filled a more senior position in Germiston.

According to the website Artefacts, he soon opened his own practice in Germiston but continued to live in Johannesburg. He became a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1911, his sponsor, J.S. Bowie, confirming that Cooke had been working as an architect for more than five years. In 1914, Cooke was nominated to the Council of the Association of Transvaal Architects.

Portrait of Percy Rogers Cooke

However, Cooke’s heart appears to have been in the theatre. He formed an amateur theatre company in 1914, named The Germiston Players. It was in his attempt to secure a theatre in Germiston, The Globe, for this company that he met Isidore William Schlesinger (1871-1949), the flamboyant entertainment and business tycoon from New York then making his mark in South Africa. Schlesinger was born in the insalubrious Bowery area of New York to a poor family of numerous children; he immigrated to Johannesburg in 1894, became an insurance salesman and began to amass a fortune as an insurance agent, but more importantly, establishing his own profitable insurance company. He was also an astute property developer and founder of the African Realty Trust, eventually becoming responsible for many property and township developments as well as farming enterprises around South Africa.

But part of Schlesinger’s heart – like Cooke’s – also lay in the theatre, that world of fantasy and pleasure. In 1913 he bought the Empire Theatre in Johannesburg and he and Cooke began their professional association. It was a natural partnership of two creative men of entrepreneurial and adventurous bent. In time, Schlesinger’s African Consolidated Theatres became the entertainment powerhouse in South Africa and led, in due course, to Schlesinger’s acquisition of numerous theatres, newsreel, movie, radio, and other investments. In working for Schlesinger, Cooke had found his architectural metier.

Schlesinger appointed Cooke as the architect to African Consolidated Theatres and together the pair formed a great team. Cooke became involved in designing theatres for Schlesinger in many places in South Africa – Benoni, Brakpan, Springs, Witbank, and the Colosseum Theatre in Johannesburg – as well as the de lux cinema in Durban in 1926 and The Playhouse in that city. He also designed the Alhambra Theatre in Cape Town in 1929. Of particular note was the Capitol Theatre in Pretoria, opened in 1931, that graces the cover of Swart and Proust’s book, Hidden Pretoria, and is described in a chapter, together with photographs of its current fate.

Colosseum Theatre

Playhouse (The Heritage Portal)

Pretoria Capitol Theatre entrance by Dotman Pretorius (Hardijzer Photographic Collection)

These were not, however, merely theatres of a semi-Shakespearian type, but ‘atmospheric theatres’, even ‘super-atmospheric theatres’. Few survive anywhere today, but in their heyday of the 1920s, they were luxurious palaces of pleasure, designed to evoke particular places, often fantasy and magical places, using projectors, sound, and ornamentation that often provided the sense of being outdoors or somewhere exotic. In these palaces of entertainment, theatregoers themselves became part of the theatrical performance.

Atmoshpheric interior of the Colosseum in Johannesburg

Schlesinger’s work took Cooke to Europe and the United States in 1927 and in 1930 to study innovative theatre design. In time, Cooke became a Member of the Society of Architects, London, and a Member of the Acoustical Society of America. He died in 1958.

Entertainment is an industry based on imagination and fantasy and, although I have not yet been able to verify that the company named South African Lidos Ltd belonged to Schlesinger, I strongly suspect that it did. Certainly, Cooke drew up its design in February 1936.

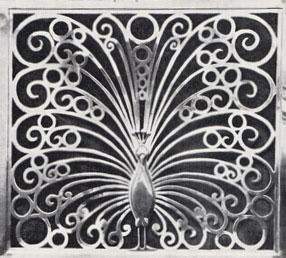

Importantly, a model of the proposed Lido was constructed to attract investors and was on display, according to the Prospectus, ‘in the windows of Messrs. Norman Anstey & Co., Joubert Street’. The model was made by René Shapshak, himself a notable figure in the Johannesburg art world and, according to Clive Chipkin in Johannesburg Style, ‘underrated [as a contributor] to Johannesburg’s modernity’. Born in Paris in 1899, Shapshak studied at the École des Beaux-Arts there as well as in London and Brussels. He emigrated to South Africa early in the 1930s, living in the Johannesburg suburb of Yeoville. He taught art, executed numerous commissions – paintings and illustrations. He was a founder, and founding Committee member, of the Transvaal Art Society on its establishment in 1937, together with luminaries like Walter Battiss. Shapshak was responsible for the attractive low relief panels of Broadcast House, a heritage building in Johannesburg, designed for Schlesinger in 1935 – who had rescued earlier radio stations – by the architectural firm of J.C. Cook and Cohen. The Shapshak family left South Africa to settle in New York in the mid-1950s, and René died there in 1985.

René Shapshak

Old photograph of Ansteys

Old photograph of Broadcast House (Seventy Golden Years)

Broadcast House grille by Shapshak

There is a stamp on the reverse of the photograph of the model, with its rather tattered edges, attesting to the fact that it was taken by Johannesburg photographer and cinematographer, H. (Henry) Duncan Abraham (1900-1979). Abraham began his photographic career after World War I, in which he served in the Royal Air Force before studying at the University of Leeds. Perhaps not surprisingly, he was a pioneer of civil aerial photography in South Africa but, as a newsreel cameraman, he also photographed the 1936 Empire Exhibition in Johannesburg, the 1947 Royal visit, the discovery of the coelacanth, and other important events including political protests and the Treason Trial. Later he became a documentary movie photographer, filming Laurens van der Post’s ‘Lost World of the Kalahari’.

Given the high profile of the people involved in the Lido initiative, it might well have been successful. There were probably many reasons why it failed to become something like Sun City’s Valley of the Waves did in the 1970s and 1980s – a time of a very different political and economic context. It was in those later decades that Sandton came into being as a town, and that property developers decided to back Sandton City, a shopping centre, rather than a Lido. It is also possible that, in the 1930s, private swimming pools became more popular in Johannesburg. Perhaps too, the Depression had detrimentally affected the investment appetite for adventurous, ambitious, and very expensive, projects. In addition, in the 1930s there was no local government in the remote Sandton area – even the Peri-Urban Areas Health Board had not yet been established – and no services like water, electricity, transport or roads were provided.

Lidos are undergoing a revival in Britain at present, and it is interesting to reflect on the fact that, at one time, a Lido was planned in the very centre of bustling Sandton City that would have rivalled its British counterparts.

About the author: Jane Carruthers is Professor Emeritus at the University of South Africa, elected Fellow of the Royal Society of South Africa and Member of the Academy of Science of South Africa. She has been awarded many international visiting research Fellowships, including at Cambridge University, the Australian National University and others. She is a former President of the International Consortium of Environmental History Organizations, the Southern African Historical Society, Chair of the Academic Board of the Rachel Carson Centre Ludwig Maximilian University, Munich, Editor-in-Chief of the South African Journal of Science, and recipient of the Distinguished Scholar Award from the American Society for Environmental History. She pioneered the discipline of environmental history in South Africa and her book, The Kruger National Park: A Social and Political History (1995) has become a standard reference worldwide. Her research interests are broad, and include environment history, national parks, the history of science, land reform, colonial art, ad comparative Australian-South African history. She is the author of numerous books, as well as many book chapters and articles in scholarly journals.

Sources and further reading

- Abraham, H. Duncan, esat.sun.ac.za

- A few buildings by Percy Rogers Cooke, The Heritage Register

- Art Deco Britain: Lidos, The Lady

- Berman, Esmé, Art & Artists of South Africa (Cape Town: Balkema, 1983), p. 456.

- Britain's best lidos and seaside pools, Countryfile Magazine and

- Capital Theatre, Pretoria, Cinema Treasures

- Chipkin, Clive, Johannesburg Style: Architecture and Society 1880s-1960s (Cape Town: David Philip, 1993), p.101.

- History of lidos in the United Kingdom, Wikipedia

- Lido di Venezia, Wikipedia

- Marais Louw, Juliet, Wagon Tracks and Orchards: Early Days in Sandton (Johannesburg: Ad. Donker, 1976), pp.72-77.

- Rogers Cooke, Percy, Entry on Artefacts

- Schlesinger, I.W., Dictionary of South African Biography, Vol.II (Cape Town & Johannesburg: Tafelberg/HSRC, 1972) pp.630-632.

- Shapshak, Rene, Entry on Art Archives South Africa

- Swart, Johan and Alain Proust, Hidden Pretoria (Cape Town: Struik Lifestyle, 2019)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.