Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

If you thought climate change was still a debatable issue, look at the way the World Heritage Committee, the body responsible for international policy pertaining to heritage, is beginning to warn on the threat of climate change to heritage around the world. The World Heritage Committee, part of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), is responsible for establishing World Heritage Sites, which are sites with legal protection for having cultural, historical, scientific or other form of significance.

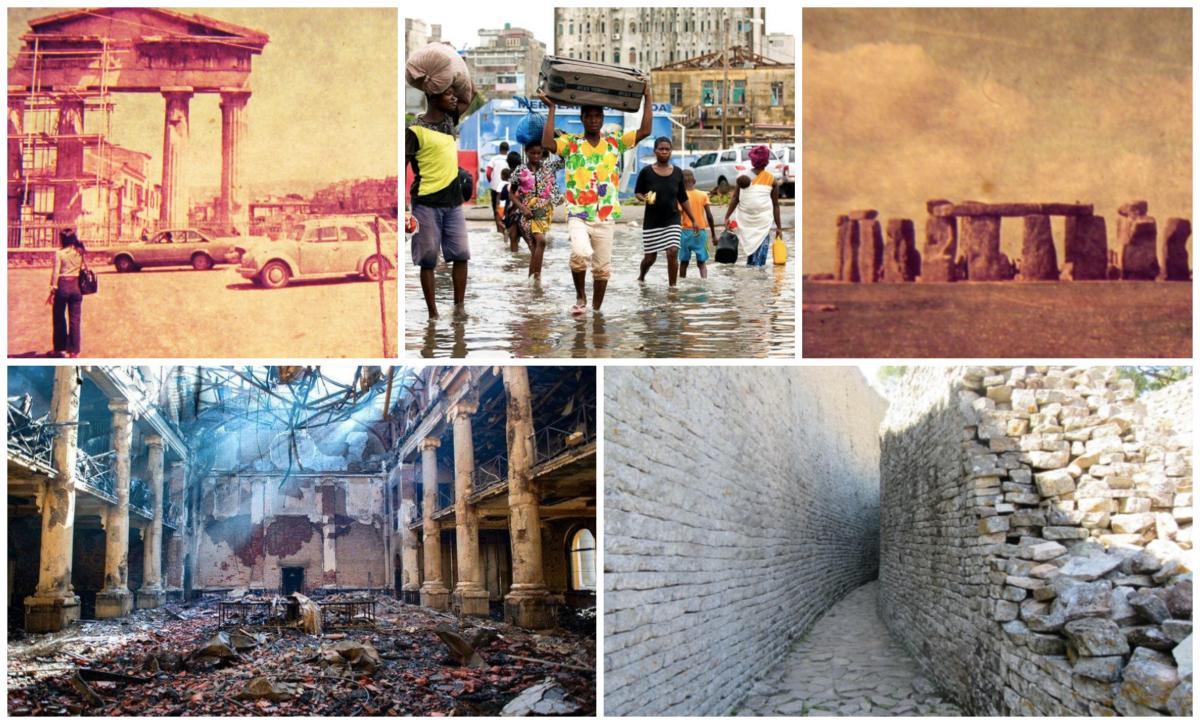

Greek architecture undergoing maintenance as a key tourism and heritage asset, 1971 (Valerie Strever)

UNESCO and safeguarding cultural heritage

The international community established the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1945 as a mechanism to safeguard human heritage around the world. The UNESCO World Heritage Convention was launched in 1975 to identify and protect examples of the world's natural and cultural heritage considered to be of Outstanding Universal Value. The Convention is governed by the World Heritage Committee and this committee is supported by three technical advisory bodies: the IUCN or International Union for Conservation of Nature acting as the Advisory Body on natural heritage, the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) representing cultural heritage.

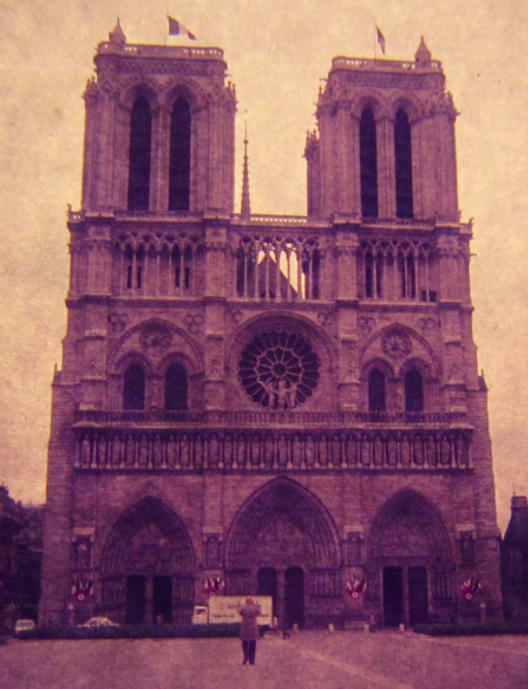

Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris in 1971. The UNESCO headquarters are in Paris. (Valerie Strever)

Climate change impacts are diverse

Climate change impacts can include actual weather-related effects (more rain, flooding, increased humidity, landslides, glaciers melting, coastal erosion), but also include the threat of associated factors of global political instability that is likely to be caused by climate change that may result in people either destroying cultural artefacts or neglecting them (Barcia 2020). Brooks and co-workers put this very strongly: “Climate change is a real and present threat to heritage across the world” (Brooks et al. 2020).

At its 29th session in 2005, The World Heritage Committee formally recognized climate change as an emerging threat to the conservation of many cultural and natural sites in the years ahead. Then, in 2006, a World Heritage Committee report on ‘Predicting and Managing the Effects of Climate Change on World Heritage’ marked a new focus in cultural heritage conservation (Dastgerdi et al 2019, and see link below). In 2006, the Committee noted “that the impacts of Climate Change are affecting many and are likely to affect many more World Heritage properties, both natural and cultural in the years to come”. The Committee requested the broad working group of experts to review the nature and scale of the risks posed to World Heritage properties arising specifically from Climate Change and come up with some suggestions on how to deal with this risk.

Information for the world’s decisions makers

The 2014 Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) noted that climate change will affect culturally valued buildings through extreme events and chronic damage to materials. Also noted was that at some point, it will no longer be possible to keep repairing heritage buildings, cathedrals, palaces, museums, monuments and other forms of built heritage. The IPCC is the authoritative source of climate science findings, acting under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), and produces an Assessment Report every four years. In 2015, the World Heritage Committee formally declared support for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), understanding the increasing climate change impacts on heritage.

Heritage as tourism asset. Family group visiting a British castle. It is a risk that these types of assets could be lost due to climate change. (Valerie Strever)

In 2017, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) established a Working Group on Climate Change and Heritage, and launched a resolution to mobilize the cultural heritage community to help meet the challenge of climate change (Garcia 2020). In 2017, ICOMOS established a Working Group on Climate change and Heritage, aimed to mobilize the cultural heritage community to help meet the challenges of climate change (Garcia 2020). The 2019 ICOMOS report, “The Future of Our Pasts: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action,” provides a multidisciplinary overview of the intersection of cultural heritage and climate change (Seekamp and Jo 2020).

What is heritage and why is it important?

UNESCO’s definition of cultural heritage relates to tangible and intangible legacies that represent the values of human societies relating to symbolic, historic, artistic, aesthetic, ethnological, scientific and social significance (Garcia 2020). In fact, culture and heritage can be anything and everything relating to the human experience, now and in the past, and can be tangible (buildings, carvings, and writings) or intangible (memory, knowledge, performance, language), or even embodied in persons (Living Heritage).

All forms of heritage are important to human society for the role they play in social well-being, identity creation and the transmitting of social identity to future generations (Clarke et al. 2020). However, there is international concern that the world is facing the loss of irreplaceable legacies from the past because of a rapidly changing world climate (Garcia 2020).

A monument of universal cultural importance, Stonehenge, England. Stonehenge was one of the very first sites in the United Kingdom to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. (Valerie Strever)

Whose heritage is important?

While UNESCO intends that local and national culture should be protected, it has been accused of having biased Western conditions and constructions of value and the past and obscures local indicators of culturally important objects and persons (Pyburn, 2008). Pyburn expresses concerns that some of the ways of validating the past may ‘create the wrong past’ in certain situations and perpetuate simplistic understandings of past cultures of ‘non-Western’ nations (Pyburn, 2008: 141). In Africa, there are 55 cultural, 44 natural, and five mixed sites and South Africa has eight World Heritage Sites.

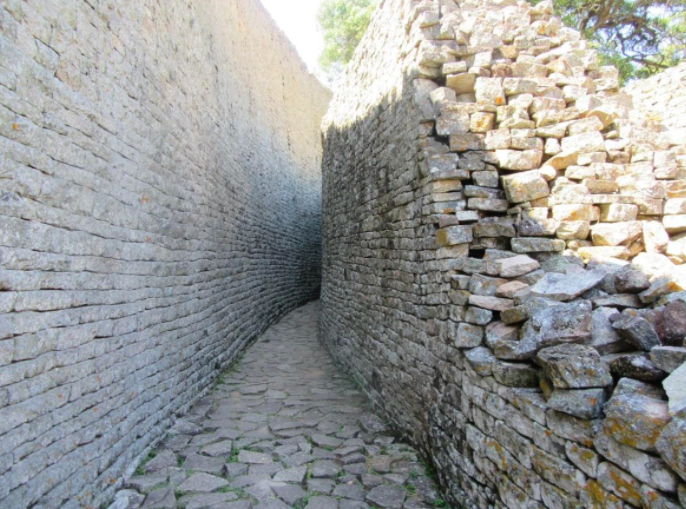

The Great Zimbabwe ruins in Zimbabwe, a World Heritage Site and site of Outstanding Universal Value. Great Zimbabwe bears a unique testimony to the lost civilisation of the Shona between the 11th and 15th centuries. (Caitlin Taylor)

Disaster Risk Reduction

Also, there is global concern about the number and increasing severity of disasters, mostly because so many people live in unsafe areas. Climate change will add to the vulnerability of people living in such areas. Under the current Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015-2030), heritage priorities are included. The heritages assets at risk from disasters include cultural landscapes, ethnographic resources, museum collections, buildings and structures. This all means that heritage assets must be integrated into disaster risk management practice, as well as recognising the role of culture and traditions in strengthening resilience in local communities.

Traditional European farming landscapes that may be at risk from climate change and disasters (Valerie Strever)

Climate impacts in Africa

The climate change impacts on Africa will be very diverse because of the wide range of biomes and landscapes throughout the continent. In southern Africa, the expected impacts of climate change will be through increased heat and fires, increased rainfall and floods, or increased aridity, depending on the region. Climate change impacts will also manifest through an increase in extreme weather events (Van Wyk, 2017). We are already seeing more severe cyclones in the southern African region, as in Cyclones Idai and Kenneth which struck Mozambique in March 2019.

People carry their belongings through flood waters in Beira, Mozambique after Cyclone Idai struck in March 2019 (Fitchett, 2019)

World Heritage Sites at risk in Africa

There are many World Heritage Sites (WHS) in Africa which are not being secured and cared for and which are on the List of WHS in Danger because of neglect and for which climate change is not the main threat. However, climate change will add to their vulnerability. Coastal erosion and sea-level rise have already damaged several African World Heritage Sites. The Roman city of Sabratha on the Libyan coast is an example of a UNESCO World Heritage Site and its future is not secure. The site is slowly being claimed by the sea as the shoreline retreats, possibly from sea level rise. Even though this and other World Heritage Sites in Africa have been declared as unique cultural assets, there are many threats to this WHS and others in northern Africa from, for example, religious fundamentalism.

Climate change not the only threat to heritage

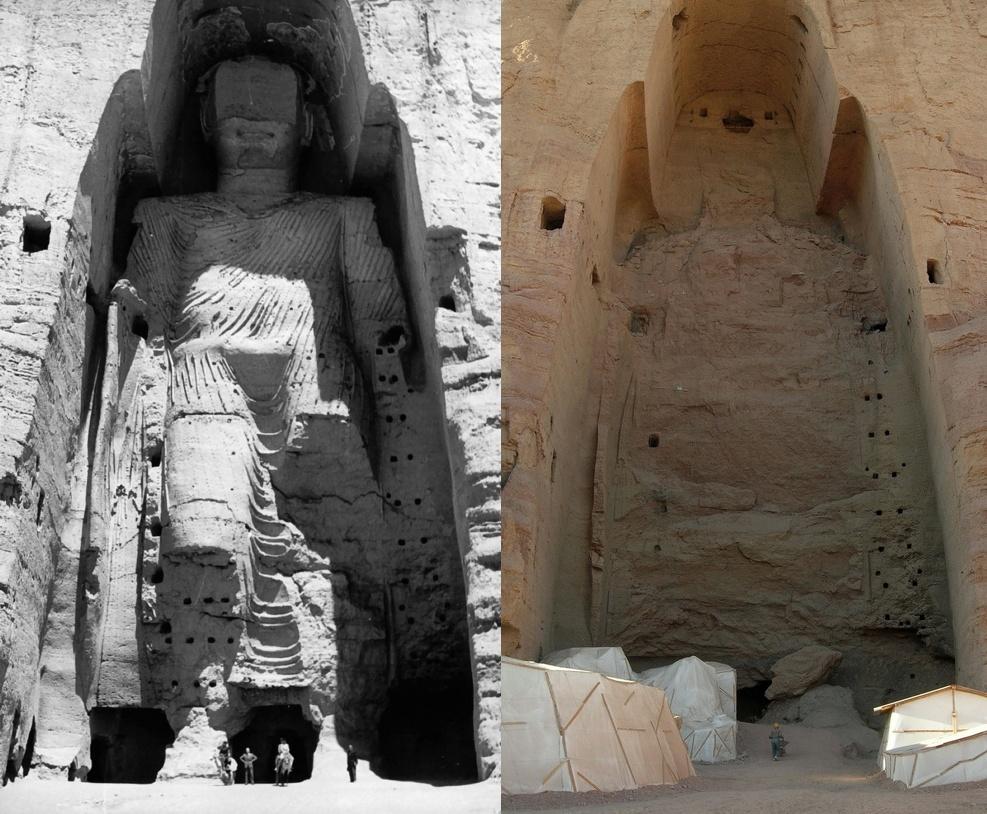

However, as we know, climate change is not the only threat to heritage: urban development and changes in land use, the neglect or demolition of old buildings, conflicts and wars, and human migration already have had a significant impact on the protection of heritage, with climate change just adding to vulnerability and risk (Dastergerdi et al. 2019). Even tourism has an impact on heritage assets. Other threat factors include armed conflict, religious extremism and the diverting of preservation funding to more urgent needs.

In March 2001, the Taliban blew up two monumental Buddha statues in Afghanistan's Bamiyan Valley, now with only the empty niches left behind, of which the above photograph shows one of the niches (Wikipedia).

A lack of discourse on climate change and loss of heritage in Africa

Currently, very few academics or policy makers are engaging with the issue of the impact of climate change on African heritage, and most of the heritage research for climate change has been done for developed countries. This means that virtually nothing has been written about the impacts of climate change on heritage on the African continent, leading to gaps in policy development and investment in heritage preservation (Clarke et al. 2020).

Although there is some research in South Africa being done to determine the threats that climate change poses to all types of heritage (tangible and intangible), the impact of climate change on South African heritage is still an underappreciated topic and needs to be matched with the substantially larger amount of research and policy attention that is underway elsewhere in the world. Van Wyk (2017) checked through all the climate change plans of the large metropolitan cities in South Africa and found none made any reference to ‘heritage’ or ‘culture’, nor was there an overarching national climate change plan for South Africa’s diverse heritage at that time. Yet, through Heritage Month in South Africa (September), the aim is to celebrate South Africa’s diverse culture and heritage. The South African government intends that the celebration of Heritage Month will lead to greater social cohesion, nation building and a shared national identity. Without panicking the populace, the discourse on loss of important heritage due to climate change now needs to be considered.

Fragile outdoor art heritage. Helen Martin's Owl House, Nieu Bethesda, South Africa. (Sue Taylor)

Loss of important heritage - fire and the UCT Jagger Reading Room

In South Africa we have recently seen the impact of fire on irreplaceable heritage with the UCT library fire in April 2021. No-one has specifically linked this fire to climate change, but it may be time to consider climate change as a risk to this irreplaceable African archive. Items destroyed in the Jagger Library fire include books and manuscripts of the UCT Libraries’ Special Collections (UCT website). The fire is believed to have started on the slopes of Devil’s Peak on the Sunday. It quickly spread to Rhodes Memorial before rapidly reaching UCT’s upper campus in Rondebosch (UCT website). With increased seasonal heat due to climate change, vegetation becomes tinder dry, and any spark or unattended fire and the strong winds, will set off a blaze. This is part of a trend of more frequent fires on Table Mountain observed over the last decade or so.

After some assessment, the damage at the Jagger Liberary was not as extensive as feared, but no doubt this event will lead to rethinking the security of all types of archives in South Africa. However, now that this has happened, future-proofing South Africa’s museums and archives may become a very important endeavour (Jeffrey 2017).

University of Cape Town’s Jagger Reading Room destroyed by fire, April 2021. (UCT website)

South Africa’s archaeological heritage – Blombos Cave

While South Africa has a great diversity of cultural heritage attributed to the various historic occupiers of this region, it is the archaeological records and sites that have the most international significance as they relate to the very early origins of human kind. South Africa has one of the longest and most-studied archaeological records of human technological, cultural, and subsistence behaviour, with finds being dated to around 76 thousand years ago (Blombos cave and other similar sites). Sea level rise might be a threat to this archaeological site.

Perforated shells thought to have been part of a necklace made and worn about 76 thousand years ago, thought to indicate that this long ago Homo sapiens society had symbolic language and thinking. (Wikipedia)

South Africa’s rock art heritage

Rock art is another major archaeological treasure In Southern Africa and may be threatened by climate change. Research is being done to understand the effects of global warming on the rock art in the Ukhahlamba-Drakensberg Park World Heritage Site and Golden Gate National Park (Clarke et al., 2020). Rock art sites in the Golden Gate Highlands National Park in South Africa are experiencing bio-deterioration due to microbial activity arising from increasing climate-related humidity (Clarke et al. 2020).

Golden Gate (The Heritage Portal)

Yet climate change is not the only threat to rock art sites, with other human threats like graffiti, mining and urban development, as well as the use of rock art caves for traditional worship, having a negative effect on the art. There are also natural impacts of time, weathering, dust, water runoff. All of these are a challenge for the long term conservation of the rock art heritage. Other rock art sites around the world are also showing accelerating degradation to climate impacts, as well as to air pollution.

South Africa’s living heritage for climate resilience

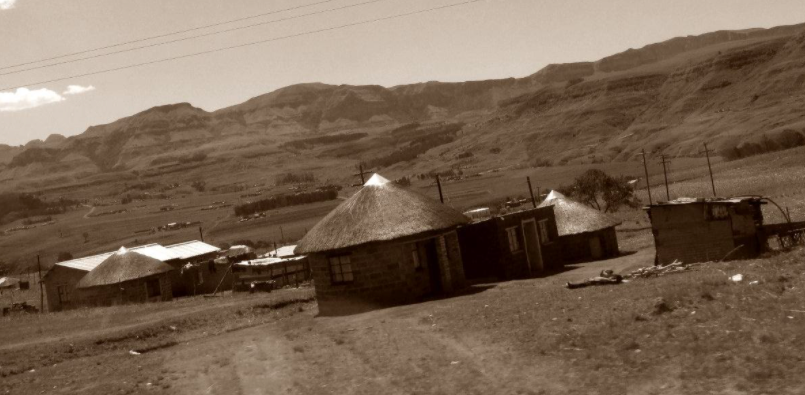

Much of Africa’s heritage and traditional knowledge is considered as ‘living heritage’, meaning that the heritage is still in us today, linked to everyday practices, and is not ‘dead and in a museum’. Living heritage also refers to the people who hold such knowledge, like crafts people and traditional healers. In many cases, traditional knowledge and skills are actually essential to ensure the proper maintenance of very old heritage properties requiring adobe, thatching or dressed stone (Dastgerdi et al, 2019).

In international thinking on climate change adaptation, it is hoped that cultural heritage and traditional know-how may form a source of practices that will lead to climate change resilience for communities. Traditional knowledge and traditional land and natural resource custodianship may be useful in returning to old ways of living that are more flexible and conservative in their use of water and land (Egeru 2012).

Traditional houses made of both local materials and modern materials, using local knowledge. Drakensberg, South Africa 2016. (Sue Taylor)

World Heritage Sites in ‘climate transformation.’

World Heritage Sites (WHS) around the world are managed with a preservationist ethos, aimed at preserving the site unchanged. With climate change it will not be possible to save all heritage sites. Moreover, there will come a time when repairing climatic impacts on a World Heritage Site exceed a financially viable threshold and rather than preserve the site, it may be better to begin to reflect on the changes underway. It may become necessary to use some sites that are changing or disappearing as a ‘memory of that place and the inherent vulnerabilities embedded in places’ (Seekamp and Jo 2020). There may also be a need for the World Heritage Convention to develop a new grouping of sites, World Heritage Sites in Climatic Transformation, to complement the List of World Heritage Sites in Danger.

Conclusion

This article was a quick glance at the very fascinating and compelling challenge of ensuring that all our diverse forms of cultural heritage in South Africa, Africa and elsewhere in the world endure through the rather dangerous climate-changed era we are entering. We may need all forms of knowledge, traditional and scientific, to successfully transition human society into a climate-altered future. Considering a worst case scenario of a ‘climate catastrophe’, it is likely that many forms of heritage will not be saved, particularly tangible assets of archaeological importance that will be lost to fires and sea level rise.

About the author: Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Her current interests encompass cities and urban greening, material culture (trash), degraded peripheries and researching the disintegration (and rehabilitation) of landscapes and buildings. She is currently a Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, QwaQwa, University of Free State (South Africa).

Sources

- “The Future of Our Pasts: Engaging Cultural Heritage in Climate Action,”

- Brooks N., Clarke J. Ngaruiya GW., Wangui EE (2020). African heritage in a changing climate. Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, Volume 55(3).

- Clarke J., Wangui EE., Ngaruiya GW., and Brooks N (2020). These African World Heritage Sites are under threat from climate change. The Conversation.

- Dastgerdi AS., Sargloini M., Pierantoni I (2019). Climate Change Challenges to Existing Cultural Heritage Policy. Sustainablity, 11L 5227. Doi:10.3390/su11195227.

- Egeru A. 2012. Role of Indigenous Knowledge in Climate Change Adaptation: A case study of the Teso Sub-region, Eastern Uganda. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge . 11(2): 2017 – 224.

- Fitchett J (2019). Tropical cyclone Idai: The storm that knew no boundaries. News24.

- Garcia BM (2020) Resilient Cultural Heritage For a future of Climate change. Journal of International Affairs, 73(1).

- Mínguez García, Bárbara. Journal of International Affairs. 2019/2020, Vol. 73 Issue 1, p101-120. 20p.

- Jeffrey T. (2017). Future-proofing South Africa’s cultural museums : climate change, heritage discourse and cultural landscapes. South African Museums Association Bulletin, 39 (1).

- Pyburn K.A. 2008. The Pageantry of Archaeology. In Ethnographic archaeologies: reflections on stakeholders and archaeological practices. Edited by Quetzil E. Castaňeda and Christopher N Mathews. AltaMira Press.

- Seekamp E and Jo E (2020). Resilience and transformation of heritage sites to accommodate for loss and learning in a changing climate. Climatic Change, 162: 41–55.

- Van Wyk L (20178). Culture and heritage sensitive adaptation measures and principles in climate change adaptation plans for South African metropolitan cities. Conference paper.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.