Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Try turning away when the Kaaimans River Railway Bridge comes into view. You can’t; it is the very definition of eye-catching. You’re intrigued. Located between George and Wilderness in the Western Cape, the bridge crosses the Kaaimans River as it enters the Indian Ocean. Whether you spot it from the river below, the Dolphins Point viewpoint above, or the N2 as you navigate its curves, the bridge and the undeveloped forested hills as they rise above both sides of the river mouth present an awe-inspiring picture. Together, they reflect the past era of railways as well as the challenging natural landscape through which the rail traversed.

The famous bridge from the river below (Wikipedia)

So in February 2021 I was surprised to learn that there was an application to construct a home on the hillside next to the bridge. The request was seeking permission to clear vegetation and undertake earthworks in order to build a dwelling, two guest rooms, and associated infrastructure on the property. For this, the owner needed an OSCA permit. The Outeniqua Sensitive Coastal Area process is the most significant tool to protect the environment in delineated parts of the Wilderness area. OSCA, however, does not cover all properties in the area by any means; in fact, it excludes many oceanfront and other properties that need such protection. But it does include the land along the river mouth.

Upon learning of the OSCA application, my first reaction was simple – What? Isn’t that bridge and adjacent land protected in some way?

As the inevitable local protest grew, I learned that no, none of it was protected. The bridge itself – so integral to the area’s character – was nothing more than a pretty picture as it supported unusable rail tracks on its unused route between Knysna and George.

I did some research, engaging with the experienced and the experts and the knowledgeable. The bridge is owned by Transnet and with the persuasive endorsement of its Tourism, Heritage & Hospitality Department, I submitted a proposal to Heritage Western Cape that the bridge be declared a Provincial Heritage Site. Such a designation was unlikely to halt adjacent development, but it was at least going to celebrate and protect the bridge itself as well as open a window into a bit of local travel history.

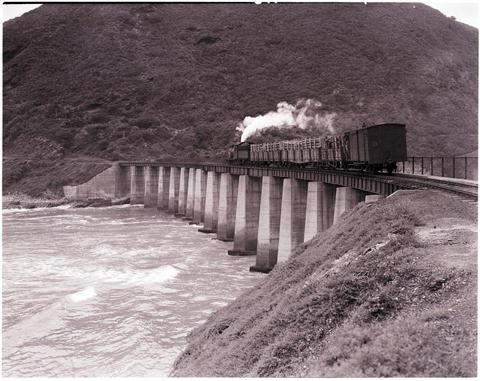

Looking back as the train crosses the bridge (Peter Ball)

Let’s start with the name, Kaaimans. There are several possible explanations:

- Keinaus. Kei (large) + aus (snake) in Khoekhoe and San. As it was unlucky to use the word for snake, it became kei (large) + aob (man), which readily became kei + man in English and Afrikaans, thus kaaiman.

- Keeromrivier. Turnabout or Turnaround River, so called by AF Beutler’s 1752 expedition as he came upon it from the west: “a certain place called Keerom by the farmers, because it is impossible to traverse it with wagons”.

- Quaimans. Referring to a crocodile (caymans) or monitor lizard (kaaiman) by KP von Thunberg in 1772. Neither occur in the river.

- Kaaimansblom. The name of the blue water lilies growing along its course.

- Kaaiman. In folklore, a Kaaiman is a mermaid-like creature known to be malevolent, resembling half-human and half-fish humanoids with glowing red eyes. They attempt to drown their victims, particularly disobedient children.

While the physical heritage of the bridge is clearly in its engineering and construction, and the railway line that spans it, its cultural heritage is equally notable. Indeed, it encompasses the uncertain origin of the name Kaaimans as well as the pioneering travellers who were determined to get through the gorge, the trail through the gorge that they and their oxen left behind, the ultimate use of the timber that the railway carried, the lives of the workers and their families that built it, and the farms that were able to transport their products.

Ox-wagon crossing the Kaaimans River in the late 19th century (Wikipedia)

Timber train crossing the bridge (DRISA)

Natie de Swardt paints the picture of the gorge:

The river estuary is at the bottom of a deep gorge some eight kilometres east of George. Here, the Kaaimans River, having been joined by the Swart and Silver Rivers, enters the sea. Not long ago, it constituted a formidable obstacle to all travel to the east of George, especially for wheeled transport. When, in the late 18th century, the need for such travel became more important, some brave souls took their ox wagons through the gorge. It was done at considerable risk to men and equipment and took much time. The gorge became known as a wagon breaker.

The 1803 description of the route through the Kaaimans River gorge by the botanist and physician MH Lichtenstein provides a vivid (and dramatic) image:

This cleft or ravine is one of the narrowest and deepest in the whole Colony ... At first the road goes very much up and down ... a steep height is then ascended ... and when arrived at the top ... the monstrous gulph is now directly beneath, and at a depth of a thousand feet below him the torrent roars over its stony bed.

... the road now descends and after having crossed the stream, ascends again a height, which, as I saw it from this point, I will not say appeared exceedingly steep, it actually appeared perpendicular; and it was not easy to comprehend by what force an empty wagon, which we saw coming down, was held back so that it was not precipitated at once into the deep.... The descent from the point where we now were could only be carried along the front of the height ... The hind wheels of the wagons were locked all the way, at other times all the wheels were locked, and the wagons were partially unloaded, the men dragging after them packages which had been taken out ... the oxen were allowed to rest a short time and then begins the most difficult part of the whole passage to ascend the opposite height. The task is most difficult at the very beginning of the ascent, for here the road goes almost as it were in steps... The greatest difficulty is when the wagon is to be drawn up one of these steps, for in proportion as the leading yokes of oxen get up the steep part upon the level, they no longer share in the draught, so that at length almost the whole of the draught rests upon the hindermost pair. Here then the strength of a number of men must be united to support the wagon behind from rolling back, while the oxen must be compelled to exert their utmost powers to draw it forward ... The three wagons, for amongst that number the lading of our single wagon had been divided upon this occasion, at length got over the most difficult part of their task, but the strength of the oxen was so much exhausted by the exertions they had been obliged to make in the midst of a hot sun, that they could not get on the rest of the way without a double span. The only resource therefore was for one wagon at a time to proceed up the remainder of the ascent, so that it was drawn by eight and twenty oxen, and thus singly the task was at length completed.

Kayman’s Gat, looking up the Swart River to the west. Drawn by John Melvill, 1815.

Nothing much had changed by 1854 when the Swedish naturalist JF Victorin passed through:

All at once you come out on a narrow strip of land with deep ravines on both sides. The road now plunged abruptly downwards, therefore the back wheels had to be locked, and after an extremely steep and stony slope we were down on the bottom. The bottom is of rocks as large as buckets and the wagon shook miserably as we went over it. Now the ascent started, which was very difficult. He who has not seen this place can hardly get an impression of how beautiful it is.

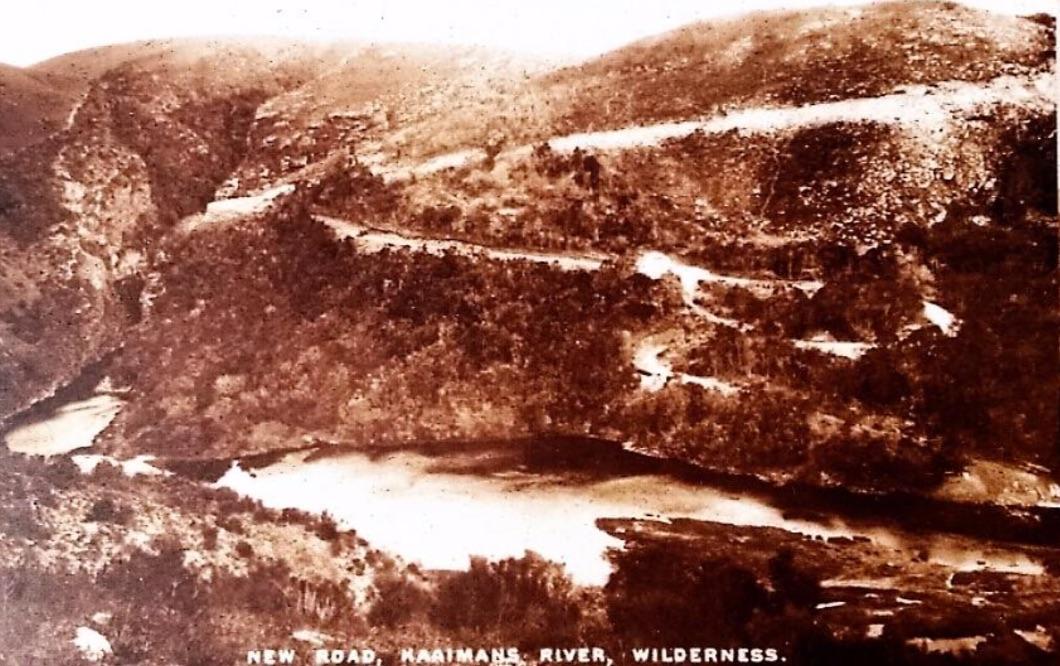

Looking westwards in the early 1920s. The "new" road comes down to the river where the causeway has not yet been built. This is roughly the same view as the Melvill painting 100 years earlier.

In the 1890s, the benefits of a railway line connecting George and Knysna were becoming clear. Thirty years of planning and preparation then ensued, with construction finally underway in 1925. The railway line and the bridge to cross the gorge were engineered by NK Prettejohn who was credited with building more railways in South Africa than any other engineer at the time. At the Kaaimans River, a temporary bridge of wood was built to make construction possible. Very long blue gum logs were likely transported from Witfontein, northwest of George, for the construction of the temporary bridge. The logs were too long for normal methods of transportation, so the tops of wagons were removed and the logs were tied and chained onto the front and back wagon axles and wheels.

To create the passage, the bridge combined bridge building technology with that of tunnelling. The method of construction using caissons that were sunk 23 meters below the level of the bed with eight-meter pylons above was a notable achievement of the time. The engineers overcame adverse geological conditions (uncommon hard clay), severe weather (with occasional extreme flooding), bad seas (aggressive wave action), and serious, frequent labour problems.

Kaaimans Bridge under construction

The 210-metre-long bridge entered South African Railways and Harbours service on 30 November 1928 with the first scheduled train crossing. After years of inactivity, railways were expanding throughout the Union. The southern Cape coast with its growing towns of Knysna and George benefited greatly from the vital transportation link.

The building of the bridge helped open the resources of the Knysna forests to the country and made the delivery of mail and medical services, the spreading of education and ideas and general travel much easier.

Large quantities of wood found their way between Knysna and George and on to the interior – wooden handles for picks, axes, shovels and other implements, as well as wood for furniture, mining and fencing.

Approaching the bridge from the east, 1977

Though freight transport was the primary impetus for the line, it became possible for passengers to travel the scenic 67 kilometres between George and Knysna in luxury, crossing the Kaaimans and several other rivers and estuaries in a matter of hours. By 1995, the route was called the Outeniqua Choo Tjoe and that’s how the tourist train came to be known. With its steam-powered locomotives, the route attracted international visitors. Railway tourism became an important part of the George and Knysna economies and supported small businesses along the line. By 2002, it carried 115,000 passengers per year, 70% of whom were foreign tourists. Photographs of the steam train on the Kaaimans Bridge became iconic.

Classic shot of the train crossing the bridge (Peter Ball)

During the last decades of the 20th century there was a movement to erect a statue of an ox at the bottom of the gorge to honour the patient animals that helped man fulfil his needs. The statue was never built but in 1993, the Wilderness Tourism Association built the Wilderness Heritage Trail – a clockwise circular route from next to the old Wilderness Post Office to Leentjesklip, then up to Dolphin Point, northward between the river and the N2 bridge (under which a memorial plaque was placed). From there it went up the steep hill, past the Map of Africa viewpoint on Remskoen Road, through some lush coastal vegetation and back to the old Post Office.

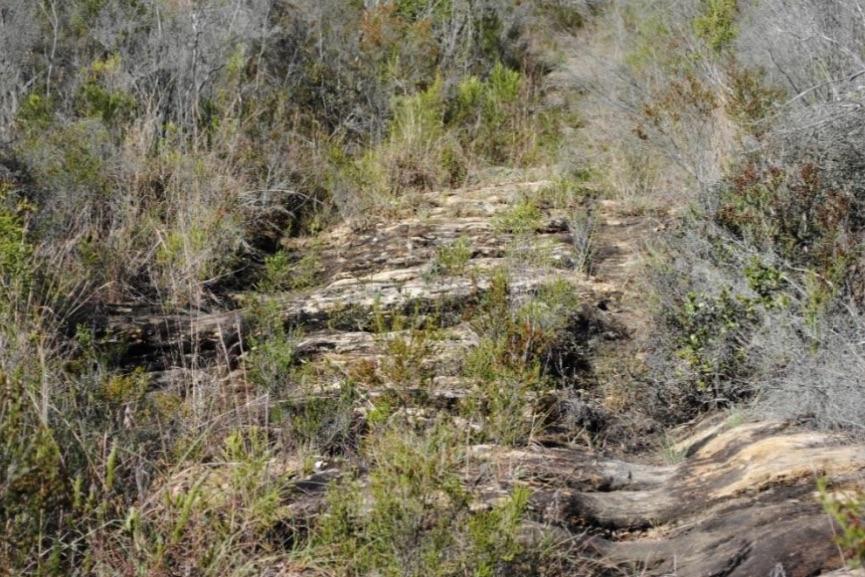

On the eastern side of the gorge, deep ruts, cut into the solid rock by wagon wheels, can still be seen. It was a first effort at preserving the heritage of the area.

* * *

The railway bridge has not been ignored. Transnet declared the bridge a preserved railway in 1992, handing it over to the Transnet Foundation Heritage Preservation in 1993. The South African Institution of Civil Engineering declared the bridge the "2019 National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark of the Year", honouring the civil engineering heritage of the country and the role that infrastructure plays in our day-to-day lives.

The George Municipality has demarcated the Kaaimans River Corridor as a statutory conservation area in its Spatial Development Framework. The Kaaimans River mouth is identified as a “Coastal Gateway: Careful management of land use and the urban-rural interface at the gateways to our urban areas (including the Kaaimans Gateway) ... forms a critical part of the future planning of the Kaaimans Bridge area."

With this rich historical record available, I submitted my application to Heritage Western Cape in April 2021, complete with several compelling letters of support. I didn’t know what to expect of the process, but it turned out to be systematic, professional, and expeditious. By November 2021, the Inventories, Grading and Interpretation Committee recommended approval to the full Council and in early December 2021, the Formal Protection of Archaeological Sites, Landscapes and Natural Features of Cultural Significance, including Structures and Unmarked Burials, known as the Kaaimans River Railway Bridge was declared.

I am hopeful that the designation of the bridge as a heritage site and the ensuing publicity will do much to not only prevent threatened disturbance of the adjacent land by incompatible development proposals, but to encourage the return of the Outeniqua Choo Tjoe and the protection and public access to the gorge. It may not be enough.

Transnet has committed to pursue a public/private partnership to restore the rail line between Knysna and George; that’s good news. Given resource constraints, however, it is unlikely that the line or the bridge itself will see improvement any time soon.

The George Municipality is committed to the protection of the Kaaimans River mouth; that’s important. To this end, it must prevent development on the adjacent hillsides and on the river banks. Note also, however, that renovations to the bridge will require serious attention to the local water distribution system as the pipes that now carry municipal water to Wilderness are currently affixed to the bridge.

The George Heritage Trust seeks to protect the greater Kaaimans gorge area; that’s welcome. Without a concerted and successful effort to secure the backing and encouragement of private landowners, however, this idea may not advance.

In other words, there remain many daunting realities to a restored bridge, an operating rail line, and a gorge story to be shared.

Aerial view of the Kaaimans River Bridge (DRISA)

* * *

The Kaaimans River Railway Bridge is a visual delight that allows the visitor to marvel at the river and the ocean, and man’s struggle with nature. We remember the engineers who designed the railway line and bridges, the workers who built them, the train drivers and stokers, the loaders and un-loaders, and the people who maintained the line over decades.

A distant view of the bridge (DRISA)

South Africa’s heritage is unique, precious, and non-renewable. With real political will, how easily a heritage designation can enhance a modern South Africa. Imagine an operational Outeniqua Choo Tjoe:

- The railway line functioning as it should, from Knysna through to George and onward.

- A safe Kaaimans River Bridge to cross.

- Transport for long-distance travellers.

- Transport for daily commuters. This is no small matter. Nearly 100 years after the bridge was completed, there is presently no public transport for working people between George and Knysna. A modern public transport system must offer alternatives to expensive taxis and dangerous hitchhiking.

- Transport for heavy freight, reducing the load on the N2 which now carries much more freight than it was designed for.

- A special adventure for tourists, with stops along the way.

- Adjacent and safe bicycle trails and walking paths along the route.

- Jobs – in planning and design, in construction and development, and ultimately in operations and services.

- An inclusive heritage site featuring the railway bridge together with the rail line and the gorge as visible symbols of human settlement in the region.

- A living understanding of the history and cultural landscape of the southern Cape coast, and to the growth of agriculture market towns and ultimately urbanization.

A passenger train drawn by three locomotives (DRISA)

Another shot of the train crossing the bridge (DRISA)

With great credit and appreciation to Natie de Swardt (Simon van der Stel Foundation: Southern Cape) for allowing me to use much of his research and writings. Thanks for suggestions and contributions to Henry Paine (George Heritage Trust), Hugo Leggatt (Author, Wilderness: Gateway to the Garden Route), Johannes Haarhoff (South African Institution of Civil Engineering), Nomasonto Ndlovu (Transnet: Tourism, Heritage & Hospitality), and several Wikipedia articles.

About the author: John Miller is retired from a career of work in developing countries that included national and local policies and projects in housing and urban development. He lived in the Waterberg (Limpopo) for many years before settling in Wilderness.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.