This concise history of pandemics in South Africa packs a lot of punch. Its republication is timely. It takes a holistic view of epidemics, is an easy intelligent read with large print and small pages. The reading time is no more than two to three hours.

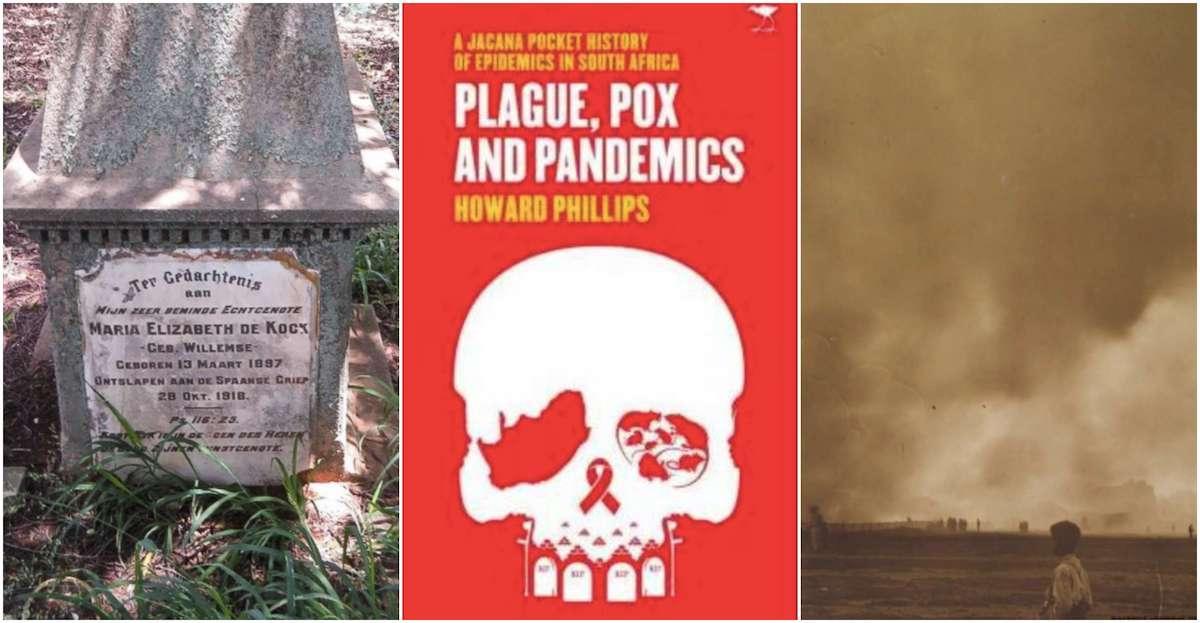

Plague, Pox and Pandemics was first published by Jacana in 2012. Phillips covers five earlier epidemics and gives thought to the role of such crises in South African history. Here is a concise introduction to and reflection on the impact of five lethal diseases - smallpox in the 18th century, the bubonic plague outbreak of the early 20th century, the Spanish Flu of 1918 to 1919, Poliomyelitis in the 20th century and lastly the HIV-AIDS catastrophe of the late 20th century. History offers an anchor and point of reflection to remind humankind that we are mortal, lifestyles are finite and that earlier centuries too suffered from diseases and disasters. It is a good moment to look back to ask if and how past medical crises give any pointers to coping with the new pandemic.

Book Cover

Positives as well as negatives flow from epidemics that befall mankind; in a crisis, leaders need to show decisive leadership rather than bewilderment and should be there for all of the citizens. Mistakes in responses do happen but societies emerge from pandemics more knowledgeable and often stronger with increased input into medical science research. Most of the advances in public health followed because of hitting those lows in pandemics.

An historian of plagues, John Aberth, commented, “an epidemic tempers a society… there is no middle ground with plague. It is the litmus test of civilizations”. How a society responds to managing the fallout of a pandemic tests true humanity. Can our society nurse the sick, bury the dead, prevent the spread, protect the living and feed the desperate?

The author, Howard Phillips, is an Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Cape Town. He has pioneered research in the social history of medicine and disease. In 2018 he published a prestige volume for the Van Riebeeck Society documenting memories and recollections of contemporary survivors of the 1918 influenza epidemic in South Africa. He writes with authority and verve.

Book Cover

Each disease advanced medicine in some way but there were also negatives. Smallpox spread across continents in the 18th century with devastating consequences for the new world destroying vulnerable societies such as the Khoekhoen. Having arrived via ships landing in Cape Town the disease spread and the mortality rates were high in the first onslaught in 1713. The Dutch East India Company (the VOC) learned to manage though the response in towns was more effective than in the countryside. Smallpox was a demographic catastrophe for the Khoikhoi who in the long term could not sustain an independent lifestyle; survivors became farm labourers. Settler societies rebounded because there were influxes of new immigrants from Europe and young people acquired an immunity to smallpox. Smallpox led to the development and almost universal use of Jenner’s vaccine and bestowed immunity as a preventative measure. But some people rejected vaccination and when levels of non-immunity rose smallpox recurred in three bouts in the 19th century in the Cape. Religious thought can be a dangerous incubator of vaccine resistance because many believed that smallpox was God’s will being visited on the sinful. On the other hand missionaries and ministers also promoted such medical intervention. Public health reforms in the Cape were introduced but as Phillips explains change was extraordinarily slow, such as opening up new cemeteries when old churchyards or cemeteries overflowed. It was only in 1978 that smallpox was declared to have been eradicated globally.

Bubonic plague also came to South Africa via the ports, such as Lorenco Marques and Durban. An international sanitary conference in Venice in 1897 set out guidelines on the ideal public response; should the movement of people be restricted and if so which people? In South Africa such guidelines became a good justification for selective application to say the movement of Indian immigrants.

There is an interesting link between war and disease. The Anglo Boer War meant that tens of thousands of horses were needed for troops and transport and hence there was an increase in the demand for fodder which was imported from Argentina; rats came as uninvited imports but when the hordes of rats died in the Cape Town harbour area, the fleas carrying the plague jumped to humans and so began the trail that spread the deadly disease. There could have been a clear distinction drawn between pneumonic and bubonic plague. Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, East London and Durban became points form which the plague spread inland over a couple of years. Plague came to Johannesburg in 1904; there were actually remarkably few cases, only 113, but people panicked. A Rand Plague committee was established and set to work corralling 3178 people in the Coolie Location on the Western side of town and then moving people in mass to Klipspruit. The Coolie location in town was burnt to the ground in a dramatic display of action. Overall in Southern Africa only 958 people succumbed to the plague. A mix of common sense, isolation, medical preparedness and hysteria combined to both contain the disease but also to introduce or extend racial segregation into the now British colonial cities of Southern Africa. Hence the origins of New Brighton in Port Elizabeth and Klipspruit (later called Pimville) in Johannesburg.

Cover of the Rand Plague Report

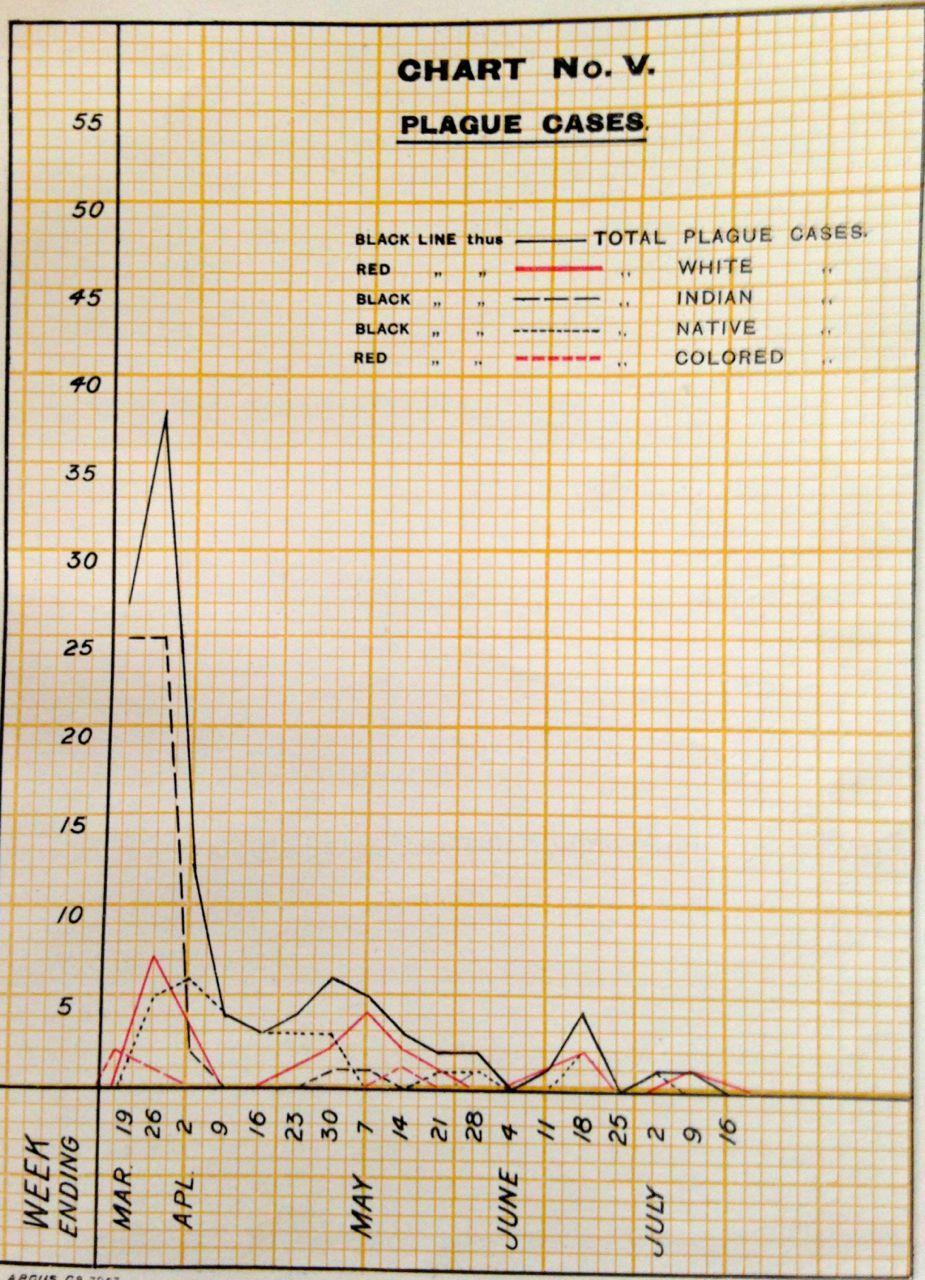

Plague Cases (1905 Plague Report)

Philip Harrison has written a marvellous study of the history of epidemics specifically in Johannesburg under the auspices of the GCRO. He offers a much more detailed case study of 20th century disease in one city. This study is published in electronic form only and is available on the GCRO website as a free download (click here to read). It is worth reading the Harrison study as a companion to the Phillips study.

In 1918-1919 the Spanish Flu was a disaster for South Africa with 6 per cent of the country’s population or 300 000 dead in six weeks. October was called Black October, again there was a blame game and people pointed fingers trying to explain the inexplicable and horrendous. It was the speed of the ravages and loss from the influenza pandemic that terrified people. Kimberley funerals went into the night, lit by car headlights. The virus was the H1 N1 and like Covid was a new strain of disease. A positive consequence was the passing of a Union wide Public Health Act and the establishment of a Department of Public Health. Phillips makes the point that the Flu epidemic of 1919 was an accelerator of changes that were already under way - a national system of public health, the construction of hospitals, spreading of popular health education, efforts to address “poor whiteism,” the spread of independent Zionist churches are some examples.

My grandfather was lost to the flu in 1919 and my grandmother was left a widow for the second time in her life with seven children and very little education on an Orange Free State farm. In fact in the case of that family the impact of the epidemic catapulted them into poverty, a couple of children had to be put into a home, boys left school early and took up a trade, girls became seamstresses and skilled lampshade makers. My mother was the second youngest daughter and the only child to matriculate, and go to night school and become an accountant in Johannesburg. My mother missed her father all her life and though she was only 5 years old, she remembered the moment her Dad died and poignantly shared that death with me some 50 years later when I was a teenager. My grandmother survived by making school bloomers for the Bloemfontein girls schools. It was a home industry.

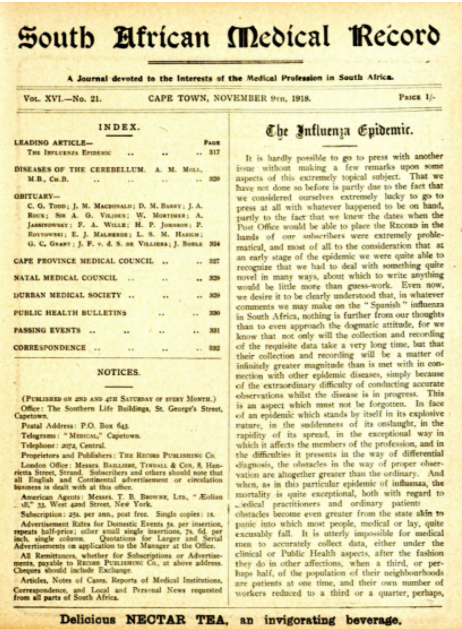

The SA Medical Record for November 9th 1918 carried a lead article on the influenza epidemic

The personal stories are the ones that bring home the impact of infectious disease when it sweeps across the land. It is the human loss, pain, grieving when a death happens prematurely and individuals do not live out their Biblical three score year and ten that is remembered in families. It is not simply about a gouging out of the normal demographic patterns. Epidemics reverberate through generations as the lives of children are blighted. The private life is more important to the individual than the public statistics. There is an emotional psychological and a material cost borne by those left behind when excess deaths overwhelm.

Johannesburg - a grave of a victim of the Spanish Flu 1918 (Sarah Welham)

In my lifetime I have lived through the infantile paralysis or poliomyelitis epidemic of the 1950s and like Howard Phillips I too have childhood memories of celebrating the breakthrough of the Salk and Sabine vaccines. I recall the palpable fear in families. Parents showed their anxiety, wanting to isolate and shield their offspring from catching polio; stopping us from catching the school bus and it was an end to ballet dancing lessons in the local hall when one girl, the most promising ballerina of our galumphing troop was crippled for life by polio. Phillips covers polio not as an event that happened in one epidemic but as a far longer pandemic over several decades. He explains why this was “the middle class plague” through a half century from 1918 to 1963. Oddly it was a disease that was more prevalent in areas with good sanitary facilities than in poor working class areas. Children where sanitation was poor acquired an early immunity to a silent or less damaging strain of polio and so were protected, but children in sanitised privileged homes with water closet toilets and running water were not immune. This meant that in South Africa polio was a European rather than an African disease. Paralytic polio was a most devastating disease because the victim was damaged for life. My husband relates how he and his brother both caught polio though were the lucky ones as both recovered but remembered the illness and the panic of their parents. To gain a real understanding of what this disease did visit the Adler Museum of medicine at Wits and see an Iron Lung which is an awkward huge clumsy machine but was a life saver. Drs Salk and Sabine were the heroes of our generation and again it was vaccination that saved lives and brought back normality.

The final pandemic discussed in this book is the HIV/AIDS pandemic and it is a disease with an opening date (1982) but no closing date because we are still living with and dying from this disease. In 2011 the disease was still claiming 500 lives a day. However by 2017, Statistics South Africa estimates the number of deaths attributable to AIDS in that year was 126,755 or 25.03% of all South African deaths. It is sobering to realize that that figure is double the number of deaths officially recorded as due to COVID. In the years prior to the availability and public health system distribution of antiretrovirals and the management of mother to new baby transmission with nevirapine, HIV AIDS destroyed millions of young lives. It is shocking that an outbreak became an epidemic. Arriving at the point where people live with HIV and manage the condition rather than die from AIDS has been a long slow haul in medical science and in political campaigning because government had to be shamed into recognizing the disease and accepting responsibility to provide antiretrovirals. It was a blot on the record of the Mbeki Presidency. I mourned friends and young students – both men and women died needlessly. Phillips too had those memories of the personal impact in a pandemic.

There have been other diseases of such a magnitude that one can call them epidemic – tuberculosis , whooping cough, diphtheria and malaria are all diseases that have blighted lives and killed legions. But Malaria and tuberculosis are regarded as endemic.

The long trajectory of three hundred years of epidemics and a discussion of just five epidemics in South Africa point to the importance of concerted action and a coordinated public health response. Advances in immunology, pharmacology and virology have followed because epidemics accelerate investment in medical research. Sane, balanced political leadership matters and has to be visible and effective. Agility in responsiveness to organize relief and help for the direct and indirect victims is required, and heroes large and small emerge. All too often epidemics reveal fault lines in societies. Epidemics show up the depth of political, religious and racial fissures. Anxiety and fear can feed into mass hysteria and anticipating a millennial apocalypse. We are reminded that civilization may just be a shallow veneer.

An international pandemic is no respecter of boundaries; air travel accelerated the transmission of the Covid virus just as sea travel brought smallpox and plague to southern Africa. Most countries early in 2020 were caught out by the arrival of Covid from Wuhan; we all thought that this was a Chinese disease and Donald Trump played the demonising of the Chinese as his ace. How wrong he was and it quickly became apparent that international cooperation had to be the way forward at the very moment when world travel came to an abrupt halt.

The speed with which vaccines against Covid have been researched, tested, approved and marketed has been a success story that shows up hope for humanity and civilization.

Reading this short book about past pandemics stimulates thought about how the new crisis of our time can be addressed and suffering and loss ameliorated. History repeats itself only if we do not learn from the past.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.