To commemorate the 200th anniversary of the arrival of approximately 4 000 British settlers on the frontier of the Cape Colony in 1820, the Eastern Cape branch of the Genealogical Society of South Africa has published this substantial volume of local history, 1820 Settlers and other early British Settlers to the Cape Colony, edited by John Wilmot. At over 600 pages and 175 chapters, this book is a massive chronicle with many descendants contributing stories and family reminiscences about their ancestors. As 2020 is the 200th anniversary, it is a homage to the many ordinary English-speaking people, who emigrated to South Africa as members of the ill-conceived British government’s scheme to bring hardy adventurers, men of property, their families and recruits to settle on the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony.

Book Cover

These British settlers arrived by sailing ships in 1820 after a hazardous three month voyage. The 10th April came to be commemorated for many years as Settlers Day, but that holiday has long since been abandoned. Survival over the first two decades was heart-breakingly tough. The lives of these new immigrants in the new country were filled with disappointments and setbacks. Politically the planting of these settler parties on the frontier lands of the Zuurveld upset the dispossessed or defeated indigenous Xhosa people, who were pushed further eastward beyond the Fish River but who fought back in a series of bitter frontier wars. It was not a happy recipe for future amity. The immigrant colonial society and the indigenous society competed for land, agricultural resources and cattle. Ultimately it was about power, authority and government. However, this book does not ponder on the bigger issues of systems or the rights of land ownership. Instead it adds up to a series of personal stories of settler families. The perspective is that of specific families and what happened to their descendants in the succeeding decades and generations. They were a sufficiently large and homogeneous group so that they could and did develop an identity as English-speaking South Africans and their contributions to South Africa’s development in many fields of human endeavour has been written about and lauded. Essentially it was an immigrant group that put down roots and forged a niche for themselves in South Africa. Its sheer weight of compilations makes it an old-fashioned narrative. It does not venture into interpretation or synthesis.

It is a book that fits into the copious historical literature on the 1820 Settlers, since theirs was a literate culture. A high value was placed on establishing schools and later colleges and ultimately Rhodes University. Documents, letters, journals, photographs and archives were preserved and later published. Harold Edward Hockley wrote The Story of the British Settlers of 1820 in South Africa (published 1st edition 1948 and 2nd edition 1957) which became the standard text and has a comprehensive bibliography up to that date. Guy Butler edited a superb book, The 1820 Settlers, An Illustrated Commentary (1974) with text by Butler and John Benyon. This has a good select bibliography and with its focus on illustrations (almost all black and white) reproduced many contemporary newspaper cuttings. It is a highly collectable item. Rhodes University produced a series of 12 volumes, The Grahamstown Series, published by A A Balkema between 1968 and 1992. Many of those volumes were of the journals, letters and reminiscences of early settlers such as John Ayliff, Thomas Stubbs, Charles Lennox Stretch, Richard Paver, William Shaw and others. Perhaps best known of 1820 settler accounts were the volumes of the Chronicles of Jeremiah Goldswain, published in various formats; the Van Riebeeck society published these Chronicles in 1946 but there have been other editions. I particularly enjoyed the privately printed, Pauline Goldswain biography, The Settler named Jeremiah Goldswain published in 1983. There is a quick nod to Goldswain in the present volume which hardly does his life story justice.

This new book is a genealogical anthology. There is huge interest in 1820 settler genealogy today. Many South Africans are keen to know if their surname was on one of the 1820 settler lists. With the coming of the internet, family trees can easily be constructed and via the various databases it is possible to find birth, baptism, marriage and death certificates online. These are the building blocks of genealogical research. Many of the chapters in this book carefully list the names of successive generations. A profusion of symbols, which are familiar to the family tree researchers, indicate births, baptisms, deaths, graves, marital status, divorce, possible dates, relationship by marriage, title etc. Just the list of symbols opens up another way of looking at social history.

The editor of the 1820 Settlers, John Wilmot, says he was “coerced” into editing the newsletter of the Eastern Cape branch of the SA Genealogical Society, and believes he is the least qualified as an editor. “I never learnt how to do original work but what I did learn was how to crib. All my stories are copied from books, magazines and manuscripts, besides personal contact.” He certainly has a keen interest in family history. As a child he was particularly close to his grandfather who told him stories of the family. He can remember as a child on the farm, with his grandparents’ siblings and cousins visiting, drawing up Family Trees to tie them all in.

If you are keen on 1820 settler genealogy the starting point must be the essential lists drawn up at various dates of the settler families. There are a number of these settler lists, included for example, as an appendix in the H E Hockly book.

Geo Cory included a list of 4000 names in the Centenary souvenir, 1920 in alphabetical order. I was delighted that this booklet is available and can be downloaded (click here to view) as it contains an excellent article on Grahamstown history by Sir George Cory whose library, the Cory Library was founded on his donation. Equally fascinating, is the article by John Hewitt on the Eastern Province in pre-settler times.

C Pama, the top South African heraldic authority, published the book British Families in South Africa, Their surnames and origins (1992). Some of these families had coats of arms and crests and these are also accessible in several places. E Morse Jones brought out, Roll of the British Settlers in South Africa (Balkema, 2nd edition, 1971) and this book contains a foldout map of the location of the parties as well as clear black and white photographs of various settlers. It has been conceded a long time ago that there are inaccuracies and omissions in all lists because some intended emigrants changed their minds at the last minute and did not leave England, while other late joiners crept on board.

I mention these books because the new Wilmot book does not bother with such a list, which I think is an essential. However, there are other avoidable flaws - it lacks a bibliography and has no footnotes or source references nor are we told anything about the many contributors. Wilmot wrote more than 50 per cent of the chapter entries himself but if these various sections were contributed by others we need to know when they were written. It seems that the contributions in this book could have been written at any time. For example, Eric Rosenthal died in 1983 so his writing is an old piece. Fred Metrowitch was born in 1903 and was an active writer in the 1960s. It appears that was when he wrote these chapters.

The contents pages (all five pages) are a minimal guide to the treats in store but the authors of the chapters are not listed at the start of the book. It is only when you find a specific chapter that the author can be identified. (Tip - I wrote in the names of the authors as an aid to helping me navigate the new book)

The photographic illustrations appear to be copied from earlier books. For example, the small photo of Jeremiah Goldswain and his wife Eliza Dednam is tiny and seems to be a reproduction, possibly scanned from the same photograph produced in E Morse Jones.

There is a miniature map slipped in under the Editors Notes. It is far too small, but this same map can be accessed via Wikipedia or turn to the E Morse Jones book for a foldout of a map showing the locations of the settler parties.

A map from Wikipedia of the district and regions of settlement by the British settlers, circa 1835.

Liz Eshmade opens the current book with a short background on the scheme and the ordinary people who were recruited. The scheme was the brainchild of the British government. Lord Charles Somerset was the Governor of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope at the time and so the failures that followed are often attributed to Somerset. The story of the origins of the scheme is much more complicated. It was believed that a denser settlement of English farmers on the Cape eastern frontier would be a buffer against the turmoil and conflict of scattered Dutch farmers and Xhosa tribesmen at the Fish River. There had already been five frontier wars. The idea was to recruit farming types, farmers, farm labourers and resourceful people with useful country crafts and skills and fit them into organized parties led by leaders. These leaders would form parties and were expected to be men with some capital and substance who could maintain their party members; the settlers were allotted free land in exchange for a three year indenture.

The contract involved being servants of a leader for that period. This was the period of post Napoleonic war depression and parishes (the organizational structure for providing for the indigent) thought this was the answer to English poverty. Nothing worked out as planned. Land was allotted, but who really “owned“ the land. It is not surprising that indigenous people were aggrieved at land dispossession as the frontier crept relentlessly eastwards. Not all of the settlers were farmers, there was a limited understanding of land, suitable crops, and weather patterns. The settlers faced drought, crop failure and within a few years another frontier war. Shopkeepers did not make good farmers. £50 000 set aside for the scheme evaporated rapidly.

The common theme in so many stories was that of hardship and endurance; many of these settlers had short lives; women died in childbirth and it was not unusual for a widower to marry again. Few were suited to being farmers and it did not take long for families to want to leave their allotted farms and become townspeople.

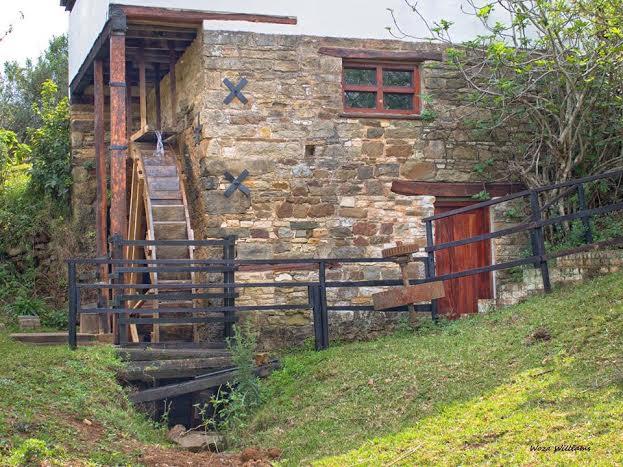

Richard and Sarah Tee came from Norfolk and their story showed resourcefulness and adaptability. Their party leader (they were in the Edward Damant Party) rejected the land allocated in the Albany district and they instead chose the Hankey District. Within two years the Tees had established the Norfolk Hotel on the Gamtoos River; Richard became a convert to Temperance and later ran a livery stable and got the contract to convey mail between Port Elizabeth and Uitenhage and went on to try other occupations in Port Elizabeth. Samuel Bradshaw, an unemployed weaver from Gloucestershire was far better suited to establishing a woollen mill and imported a spinning machine and loom but the enterprise lasted only until 1835 when it was set on fire by “marauding Xhosa” and machinery destroyed. The building survived and in 1970, the Simon van der Stel Foundation bought the mill and it was proclaimed a Historical Monument.

Bradshaw Mill (Bev Young)

In summary, the scheme was a failure but the 1820 settlers went on to establish a strong English presence in Grahamstown and surrounding Eastern Cape districts. Many 1820 settlers or their descendants became well-known names in South African history - for example, Thomas Pringle, Dick King and William Guybon Atherstone. It was Pringle who championed press freedom and Dick King made his heroic ride from Port Natal. But this book tries to capture the stories of “ordinary individuals“ though for the story to be told you needed a family to have been established and someone in the family to have been interested in finding out about the family’s ancestry.

A few months ago I bought the 3 volume history of the 1820 settlers by Karel Schoeman - a magnum opus based on the work of MD Nash (who should have had far greater authorial acknowledgement). It is all about the 1820 settlers before during and after their arrival at the Cape. The titles are Baillie’s Party - The Old World, Baillie’s Party - The New Land and Baillie’s Party - The Frontiers. I think those books must be the point of comparison. These three volumes are magnificently researched and beautifully written with a coherence. Schoeman has provided full endnotes of sources, a detailed bibliography and a professional index and a section of photographs.

After 200 years many English speaking South Africans claim descent from an 1820 settler family. This book will appeal to you if you have an ancestor who arrived in 1820.

I always remember an uncle (by marriage) whose surname was Winter who hailed from Port Elizabeth and his wife (my aunt) regarded him as very special because he was of 1820 settler stock. The fact that he was a barber in Orange Grove took nothing away from his claimed illustrious origins. I remained impressed.

Perhaps there is a chapter in this tome on your roots. The book is a treasure house of anecdotes and narratives about dozens of families - the names are redolent of English, Scottish, and Irish origins and culture. There are 157 chapters (most are very short) and too many names to list all of them. There were Atherstones, Cowleys, Pringles, Flemings, McClelands, Melvills, Wisemans, Kolbes, Whitens and Orrs among many others who feature. Each chapter is self-contained and so it’s a book for dipping into at leisure but beware it is a chaotic book as there is no particular or obvious chonological, alphabetical order or say a geographical grouping.

Fortunately, for such a large volume (over 600 pages) the book has been sturdily produced; the binding is hardcover and the typescript is easy to read. Many small black and white photo reproductions add interest but don’t do justice to the subjects. There are no coloured plates.

Thrown in for one’s free education are odd chapters on diverse subjects such as the Mountain Passes of the Cape, the South African recipients of the Victoria Cross, St Helena Island, Shipwrecks on the Eastern Cape Coast, a piece of religious embroidery in St Paul’s Cathedral, London with a South African connection, the Campanile of Port Elizabeth and a chapter on Sir Percy Fitzpatrick. All very interesting and entertaining but belonging in the snippets box of South African history.

Campanile (The Heritage Portal)

There is one contribution in Afrikaans along with another half a chapter. There needed to be a far stronger editorial hand and here is a case where a shorter book would have made for a more focused study and far greater coherence. I should also add that the subtitle can be confusing, as it states “and other early British Settlers to the Cape Colony”. The questions then arise, what differentiated the 1820 settlers and the other “early British“ arrivals. There are two chapters on the Schreiner family, but not sequential so there is some repetition on the life and political career of Will or W P Schreiner.

The benefit of a genealogical history is its breadth and the many fascinating stories of the families of 1820 descent and the genealogical orientation. There are many voices speaking here. No doubt this is a book that will provide many hours of reading pleasure but the weakness lies in the lack of context and interpretation of how the arrival of these 4 000 settlers impacted on the lives of the people who were already on the frontier; how did the frontier and the pioneering farming life translate into a new economy.

Sadly there is no attempt at review and reinterpretation in the light of new writing about the Eastern Cape and the people whose work should have been included such as Jeff Peires or Jackie Cock are missing. Genealogy I suppose is about family history but it makes for limited interest. Too many chapters make for a sort of squirrel nut approach to history; there is no interpretation, no backbone to the book and no attempt to be inclusive in the writing.

The book can be ordered via Footprint Press (click here to visit website). 2020 price guide - R650 plus a delivery charge or as a special offer Johannesburg Heritage will order you a copy from the publisher at the price of R 550 a copy. Email mail@joburgheritage.co.za

Main image: In 1874 Thomas Baines painted a oil painting of the landing of the British settlers in 1820 in Algoa Bay,. Baines painted the painting in Port Elizabeth. Although painted some 54 years after the coming of the 1820 settlers it is regarded as an accurate historical narrative. It is in the Iziko William Fehr collection in the Castle of Good Hope, Cape Town.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand and chair of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.