Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The first permanent photograph to have been recorded was taken by the Frenchman Niépce during 1826 (after an eight-hour exposure). A fellow countryman, Daguerre, perfected the capturing of a permanent image by inventing the first practical photographic process during 1839. This photographic end result became known as the Daguerreotype.

In South Africa, photographers have been commercially active since 1846, initially establishing themselves in the larger towns within the Cape, but soon moving into the smaller towns and other provinces. There were more than 230 photographers active in the Cape between 1846 and 1870 alone.

Photographs produced by South African based photographers on the extraordinary popular Carte-de-Visite have become of significant value from a historical and research perspective. They have become historical documents in their own right which need to be treasured in that much can be gleaned from these photographs with regard to our social and photographic history.

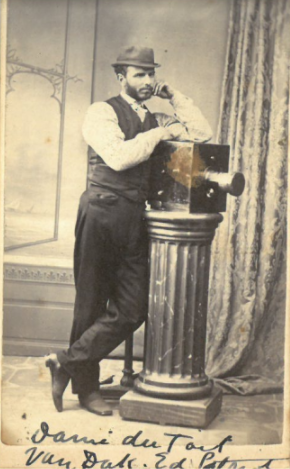

Danie du Toit – Editor of Patriot. An exceptional image due to the inclusion of the studio camera – Circa 1875

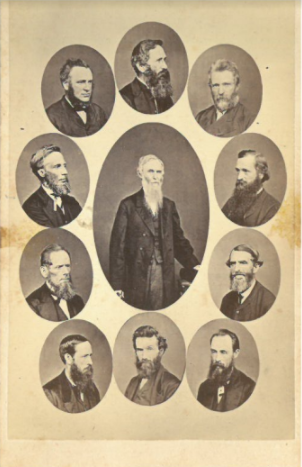

A combination image. Unusual for that era. Sitters have not been identified to date – Circa 1872

Once again, the French were in the forefront. Another Frenchman, namely Disderi, patented the Carte-de-Visite in 1854.

The paper-based Carte-de-Visite photographic format followed the Daguerreotype and Ambrotype (another format which was introduced shortly after the Daguerreotype) which were both cumbersome and expensive glass-based photographic end results.

A Carte-de-Visite (Also referred to as Carte or CdV) is a piece of cardboard measuring about 11.4 by 6.4 cm, the size of a formal visiting card of the 1850’s, with an attached photograph of nearly the same size.

In South Africa, the Carte-de-Visite resulted in a huge following from 1861 onwards. The introduction of the Carte-de-Visite provided photography with its greatest impetus thus marking the beginning of one of the most important periods in South African photographic history.

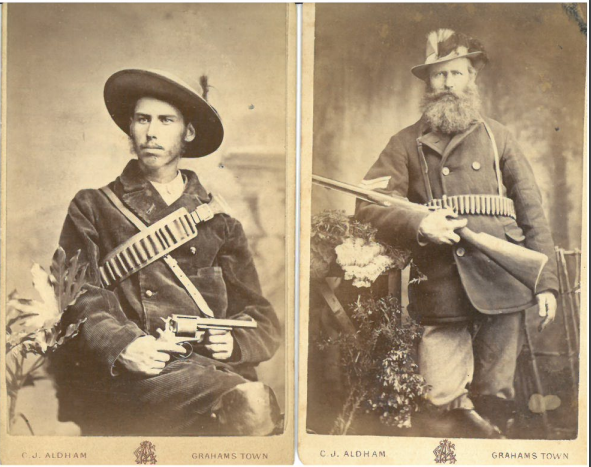

Grahamstown townguards (?) photographed by Aldam – Circa 1885. Chap with revolver on his lap has been identified as one Emslie

It has even been suggested that well over 90% of photographs taken during the latter part of the 1800’s was either of the Carte-de-Visite or Cabinet Card formats.

The Cabinet Card, three times as large as the Carte-de-Visite, was first introduced in Europe during 1866, but did not manage to capture the South African photographer or public’s attention like the Carte-de-Visite. The Carte-de-Visite reigned supreme and was still growing in popularity in South Africa during 1866.

The first Carte-de-Visite camera in South Africa was owned by Frederick York of Cape Town (February 1861). York received this camera as a present from H.R.H. Prince Alfred. A few months later Arthur Green took over the camera and started advertising Visiting Card Portraits from May 1861 onwards. This camera could take four portraits on one plate.

Later cameras were capable of taking eight images on one plate. From the contact print, the eight images were cut and pasted onto specially printed cards typically bearing the name of the photographer either on the back or front of the card. However, some photographers, mainly the less professional, did not bother to include their details on these Carte-de-Visite.

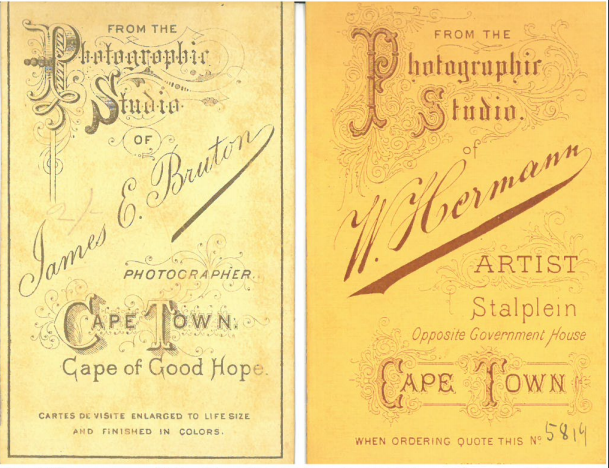

Many photographers also ensured that the back of the Carte-de-Visite had some unusual artistic design.

Backs of some Carte-de-Visite showing artistic advertising. These cards were typically preprinted in bulk in Europe.

Sadly, the details of the subject (or the sitter) were often not recorded, which leaves a void when conducting research. Where names of the sitters were recorded, these were mainly recorded on the back of the card, sometimes in handwriting that is difficult to decipher.

Not all South African, and mainly Cape-based, photographers immediately took to producing Carte-de-Visite. This could have been due to new photographic equipment required, but possibly also that some of them questioned the profitability of this cheaper end product. Due to the competition becoming fierce, most photographers eventually cottoned on.

With the vast expansion of photography during the mid 1800’s, visually recording the likeness of every single member of a family or friend created huge excitement. The craze to obtain Carte-de-Visite photographs was coined “Cartomania” in Europe. Although this craze was not followed with the same intensity in South Africa, South African’s also attempted to obtain photographs of well known personalities such as politicians, actors and actresses, singers, soldiers or religious figures. Few families, whether rich or poor, went without a photographic album filled with a mix of photographs of family, friends and well-known personalities. Carte-de-Visite photographs were relatively cheap and therefore within the reach for millions worldwide.

Unusual portrait image by South African Photographic Saloon of five travelling actors – Circa 1870’s

Many of these leather-bound Victorian photographic albums have sadly been destroyed or thrown away. They contain a huge amount of useful information on our country’s social and photographic history.

The quality of early Carte-de-Visite, in some cases, left much to be desired, especially those in smaller towns, as many tried their hand at earning an income from this new-found need to have images captured.

Bull and Denfield (1970) cite one such classic example:

“A Mr. J McDermott, felt he was doing the public a service by inserting the following notice in the George Advertiser of December 22, 1864:

The inhabitants of inland towns, between Cape Town and the frontiers are hereby warned that a person traveling in the capacity of a portrait-taker, with a wife and two children, a cart and four horses, is a complete take in, and cannot produce a good picture. He is a Scotch mason, and of small statue (sic). He will produce you likenesses well executed, which have been taken in Cape Town by an artist, and he will tell you that they are his own. This is obtaining money under false pretences. Take care, as you will get no correct likenesses”.

The earlier Carte-de-Visite were the simplest, featuring full length figures either standing or seated against plain or classical backgrounds. Later, photographers introduced a range of props into the studio, such as painted backdrops, balustrades, curtains, pillars and chairs.

Young Scottish lad. Taken by Hermann in his Cape Town based Studio – Circa 1890

Backcloths were painted, accompanied by pedestals or furniture for the sitters to lean on during the photographic exposure. The photographer also had to include, unseen to the camera, a stand with a kind of head clamp to put a vice-hold on the head of any person who could not otherwise remain motionless during any long exposure. (Exposure times varied between a few seconds to as long as a minute depending on the amount of light available, as natural daylight was generally all that was available). These stands needed to be completely hidden in the finished photograph. They were therefore precisely positioned behind something, an article of furniture, a drape, or, indeed the subject of the photograph.

Often we wonder why people in these photographs never smiled. The answer is simple – due to the long exposure time people could not smile as the sitter’s face would have been blurred or out of focus due to movement.

Colour photography did not exist in the nineteenth century. Some photographers either requested an artist to do colouring or simply did it themselves as many of them diversified from art to photography. Coloured Carte-de-Visite are however not common. Many efforts at hand-colouring were not done professionally. One such exception is that by the Graaff Reinet based photographer William Roe.

Unusual hand-colored image of a Cape Malay woman photographed by Cape Town based James Bruton – Circa 1888

What also makes the Carte-de-Visite appealing from a historic and research perspective are children, hairstyles (including beards and mustaches), clothing, hats, animals, toys held by children, musical or other instruments, furniture and books.

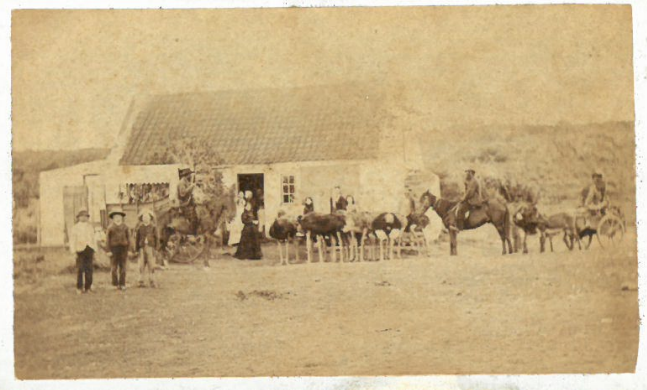

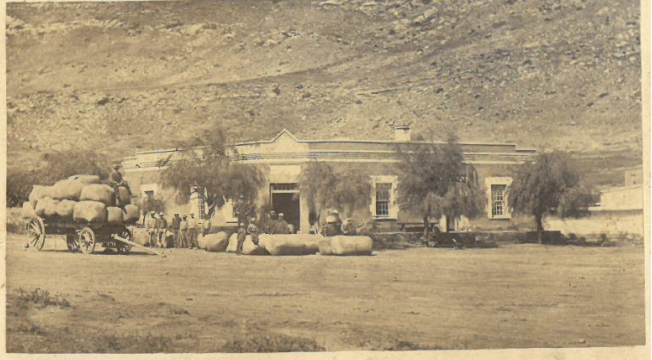

Carte-de-Visite were not only taken of people. Street scenes, scenic views, buildings, ships and historical places were also photographed. Carte-de-Visite were also produced in creative ways. From time to time, composition Carte-de-Visite can also be found, where smaller images of a person appearing in different poses have been placed on a single card.

Carte de Visite images produced outside a studio were rather unusual. This scene is of an unknown farm location in the Cape. Photographer unknown. Circa 1870’s

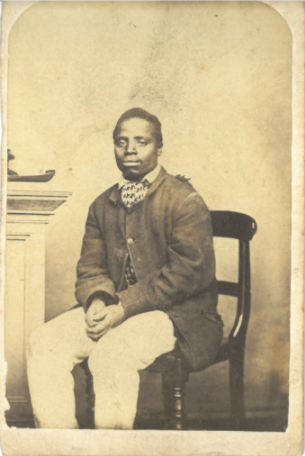

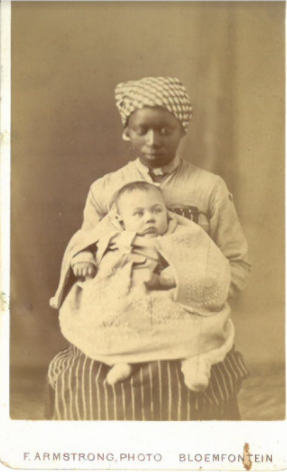

Sadly, not many Carte-de-Visite exist of South Africa’s black population in an informal or social setting. Most Carte-de-Visite taken of the black population were for research purposes and are mainly to be found in museum archives.

Unknown sitter. Taken at the South African Photographic Saloon based in Cape Town. Circa 1870

Unknown sitters. Taken by Armstrong at his Bloemfontein based studio. Circa 1890

Carte-de-Visite were cheap in their hay-days but with some almost 150 years old they have most certainly become invaluable to our history. Let’s preserve our photographic history!

This article was previously published in Village Life (No longer being published).

Carol is passionate about South African Photographica – anything and everything to do with the history of photography. He not only collects anything relating to photography, but also extensively conducts research in this field. He has published a variety of articles on this topic and assisted a publisher and fellow researchers in the field. Of particular interest to Carol are historical South African photographs. He is conducting research on South African based photographers from before 1910. He is also in the process of cataloguing Boer War stereo images produced by a variety of publishers. Carol has one of the largest private photographic collections in South Africa.

References

- Baldwin, G. (1991). Looking at photographs – A guide to technical terms. British Museum Press, London.

- Bensusan, A.D. (1966). Silver Images. History of Photography in Africa. Timmins, Cape Town.

- Bull, M. & Denfield, J (1970). Secure the Shadow. The story of Cape Photography - From its beginnings to the end of 1870. Mcnally, Cape Town.

- Harker, M.F. (1975). Victorian and Edwardian Photographs. Charles Letts, London.

- Mathews, O. (1974). The album of Carte-de-Visite and Cabinet Photographs 1854-1914. Reedminster, London.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.