Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the article below, journalist Lucille Davie tells the wonderful story of the rediscovery of the grave of Enoch Sontonga, composer of Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika. The article was first published on the City of Joburg's website on 11 January 2002. Click here to view more of Davie's work.

An act of vandalism at Braamfontein Cemetery helped locate the missing grave of Enoch Sontonga, the man who wrote South Africa's national anthem, Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika (God bless Africa). The discovery of the grave, now a national monument, ended months of patient and ingenious detective work by city officials, archaeologists and historians.

Sontonga, a teacher and lay preacher, wrote the first verse and chorus of the anthem as a hymn for his school choir. He died in obscurity in 1905, aged just 33, seven years before the African National Congress launched his hymn into prominence as an anthem of black struggle against oppression.

The search for Sontonga's grave started by chance at a dinner by the National Monuments Council in honour of then-President Nelson Mandela, in Cape Town in late 1995. A relative of Sontonga's who was present told Mandela that Sontonga was believed to be buried somewhere at the Braamfontein Cemetery in Johannesburg. Mandela called for a memorial to Sontonga in the cemetery, to be erected in time for the first post-apartheid Heritage Day.

Lych Gate Braamfontein Cemetery (The Heritage Portal)

Braamfontein Cemetery (The Heritage Portal)

The National Monuments Council instructed the Johannesburg Parks and Technical Services Department to investigate, with the project headed by Alan Buff, presently senior manager of Technical Support & Training.

But finding the grave proved far from simple. It took Buff almost nine months of intensive research - a lot of it in his own time - to locate the exact spot. One problem was that in the early seventies, the city council covered much of that section of the long-disused cemetery with a metre of soil, and grassed it over, hiding all traces of the graves. Another problem was that although records of several graves under the name of Sontonga could be found, no grave could be found under "Enoch Sontonga".

Hal Shaper, author and musician, who at the time was researching the history of Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika, suggested looking under "Enoch". This tip proved correct: a grave number was discovered: grave number 4885, buried in the Christian Native section on 19 April 1905. Sontonga had died unexpectedly the day before, on 18 April 1905. Buff checked his death certificate - he died of gastro-enteritis and a perforated appendix. "It was a common cause of death at the time - the water was not very safe," says Buff.

10 acres, 600 graves

The Christian Native area consisted of three sections covering 10 acres, with 600 graves - but the plan for that section of the cemetery was missing. This called for sharp detective work.

Says Buff: "I took all the registers, marked off sections one by one and came up with an L-shape plan within which Sontonga was likely to be buried. But the problem was trying to establish the width of the pathways between graves and in what direction the graves were filled."

Infra-red photographs taken in 1979, which reveal ground disturbances by measuring variations in ground temperatures, helped solve some of these problems: they indicated grave shapes and pathways.

The Department of Archaeology at Wits University was called in to do a shallow excavation to help establish the precise burial spacing.

"This helped bring the search down to a triangle of graves of 40 square metres, containing 33 graves. I bought a bottle of whiskey in anticipation of the find," says Buff. But this still didn't answer the question: where was grave 4885?

"At the end of February, in the middle of my investigations, vandals removed tablets from the cremation wall," says Buff. The vandalism prompted Buff to take a look at documents from the cremation section of the cemetery - which he had not considered before - and there he discovered a plan of the cemetery.

"It was the original cemetery plan and showed the starting point of the section where Sontonga was buried. I could now count the graves and establish his grave - the 112th grave in the second portion."

The dig uncovered a grave number plate with 17 inscribed as the last two digits, with a faint 4 preceding the 17. "A check of the register showed that a number ending in 417 was situated four graves away in the same row as 4885." Was it time to open the bottle of whiskey?

Private rites

Further checks of the registers and plans revealed discrepancies and inaccuracies in the original plans. But the final clue was that the family had registered for private rites, which gave them the right to erect a headstone at the grave.

The Wits archaeologists were called back to excavate further, and although no headstone was found, the mark of a headstone was visible. "No other graves in the vicinity had private rites, so this had to be his grave site," exclaims Buff. Grave 4885 had been located. It was time to open the bottle of whiskey.

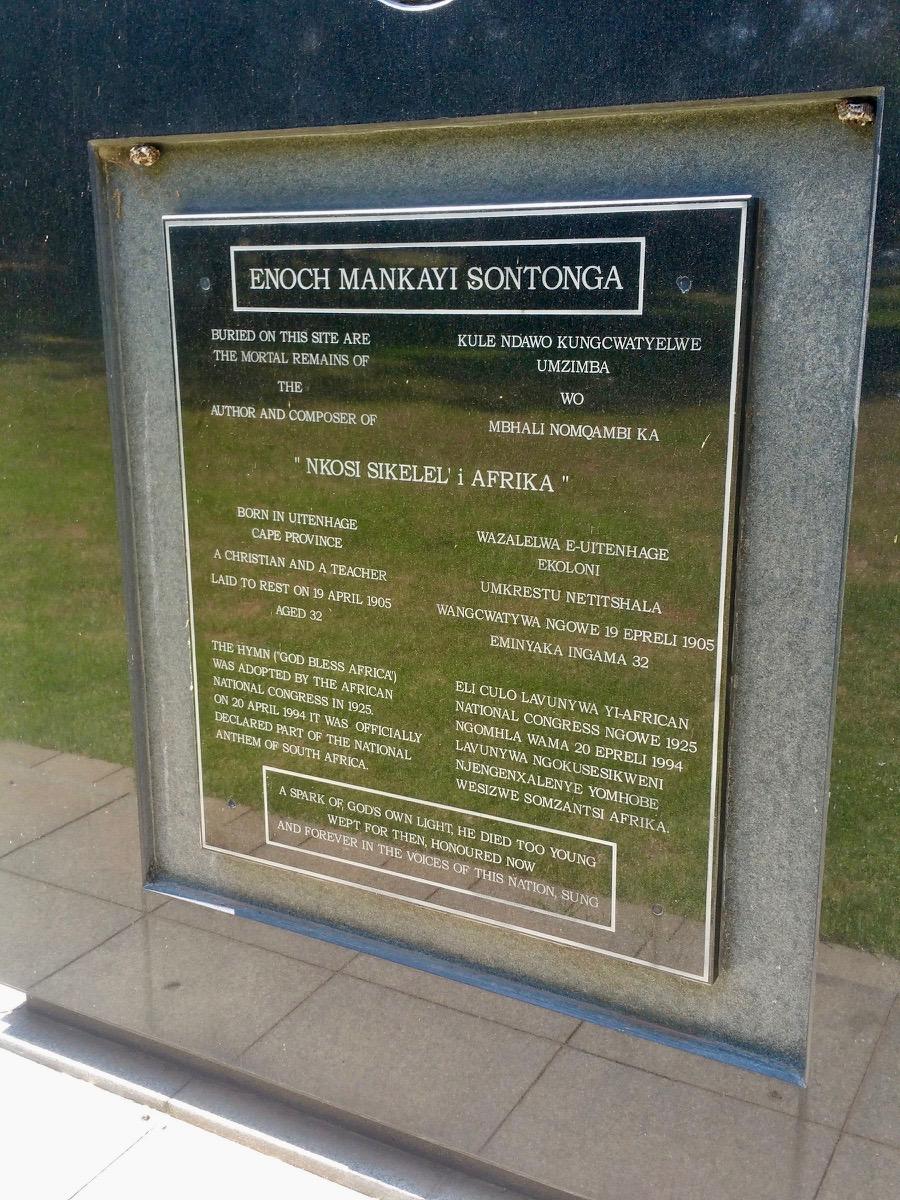

By this stage the National Monuments Council had formed the Enoch Sontonga Committee. On Heritage Day, 24 September 1996, a large, striking black granite cube was unveiled on Sontonga's grave, and the site was declared a national monument.

The granite block on Enoch Sontonga's grave (The Heritage Portal)

At the ceremony, the Order of Meritorious Service was bestowed on Sontonga posthumously, accepted by his granddaughter, Ida Rabotape.

The granite cube placed on his grave was designed by William Martinson, and is meant to signify reflections, especially as one moves closer to the monument and one's image becomes visible.

Nelson Mandela unveiled the monument, and said: "By the pride with which we bellowed your melody and its lyrics - in good times and bad - we were saying to you, Enoch Mankayi Sontonga, that with your inspiration, we could move mountains ...

"In paying this tribute to Enoch Mankayi Sontonga, we are recovering a part of the history of our nation and our continent . . . Our humble actions today form part of the re-awakening of the South African nation; the acknowledgement of its varied achievements."

As one moves closer to the monument one's image becomes visible (The Heritage Portal)

Inscription on the granite block (The Heritage Portal)

Biography of an anthem

Sontonga, a Xhosa, was born in Uitenhage in the eastern Cape in 1873. He trained as a teacher at the Lovedale Institution and was sent to the Methodist Mission School in Nancefield south-west of Johannesburg. He married Diana Mgqibisa and had a son.

A choirmaster and photographer, Sontonga wrote the first verse and chorus of Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika when he was 24, one of many songs he wrote for his pupils. Later the same year, he composed the music. The song is a prayer for God's blessing on the land and all its people. A well-known Xhosa poet, Samuel Mqhayi, wrote seven additional stanzas for the song.

Sontonga's choir sang the song around Johannesburg and KwaZulu-Natal, and other choirs followed them. The song was published in a local newspaper in 1927, and was included in the Presbyterian Xhosa hymn book as well as a Xhosa poetry book for schools.

Sontonga wrote his songs down in an exercise book, which was lent out to other choirmasters and eventually became the property of a family member, Boxing Granny. She never missed a boxing match in Soweto, hence the nickname. She died at about the time Sontonga's grave was declared a heritage site in 1996, but the book was never found.

On 8 January 1912, at the first meeting of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), the forerunner of the African National Congress (ANC), seven years after Sontonga's death in 1905, it was sung after the closing prayer. Solomon Plaatje, a founding member of the ANC, and a writer, had the song recorded in London in 1923. In 1925 the ANC adopted the song as the closing anthem for their meetings.

Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika is the national anthem of Tanzania and Zambia and is also sung in Zimbabwe and Namibia.

South Africa's anthem today is an amalgam of two anthems - Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika and the Afrikaans anthem, Die Stem van Suid Afrika (The call of South Africa), written by Afrikaans poet CJ Langenhoven in 1918.

According to Buff, Sontonga's wife, Diana, sold the rights to the song for a sixpence. She died in 1929.

Sontonga's original obituary

Enoch Sontonga's original death notice in the Xhosa newspaper, Imvo Zabantsundu, read:

"Sontonga, E. Johannesburg. On 18 April 1905 Enoch M Sontonga passed away. He was not sick this time. He, however, suffered at times from stomach ache to the extent that he would predict that these were his last days on this earth.

One Sunday he requested to take a photograph of his wife. The wife refused because she was suffering a toothache that particular day. This young man was a composer for the Church of Reverend PJ Mzimba at one location in Johannesburg. He was also a photographer and a lay preacher. He is survived by his wife and one child. He was born in Uitenhage and was 33 years old."

Lucille Davie has for many years written about Jozi people and places, as well as the city's history and heritage. Take a look at lucilledavie.co.za

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.