Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The railways of Southern Africa have developed since the mid-nineteenth century and the earliest built were based on the proven technology of the railways of Great Britain. The first railway lines were begun in 1859 in Cape Town and Durban (for more information click here for “Ox-Wagon to Iron Horse”) and were laid to the gauge of 4ft-8½in (1435mm). Durban had the bragging rights for the first railway to be completed - the “Natal Railway” which opened to great celebration on the 26th June 1860, with its first train running from Market Square to the Point, a distance of a mere two miles (3.2 km). However, the Cape Town to Wellington Railway (CT &W) was a far more auspicious undertaking and it was opened throughout on the 4th November 1863. The next 37 years leading to the turn of the century, would see a network of railway lines running many hundreds of miles from the ports into the interior as direct consequence of the major discoveries of mineral wealth, most notably diamonds, gold and coal. However, the topography of South Africa would be a major problem for the railway builders and it was realised early on that a change to a narrower gauge, in order to better negotiate the climb up the escarpment to the Highveld, was needed. The consensus was that a gauge of no less than 42 inches (1 067mm) be implemented for future railway construction (i.e. after 1872), which would become known as the Cape Gauge and extend as far as the Copper Belt in the Congo.

It therefore comes as a surprise that a gauge double that of the Cape Gauge was to be found in the docks of Table Bay, yes 7 feet (2134mm). Why was this?

Before answering this question it is worthwhile backtracking to 1835, the year when an impending exodus of Eastern Cape farmers across the Orange River and thus out of the Cape Colony was being planned (the Great Trek of 1837 to 1845) and the only means of travel then available in South Africa was on foot, by horseback or by ox-wagon.

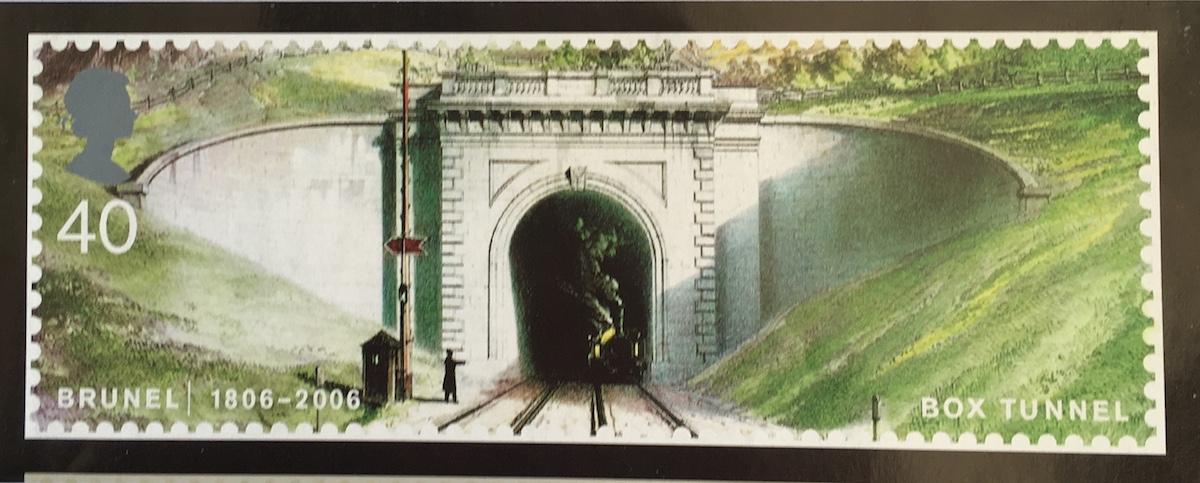

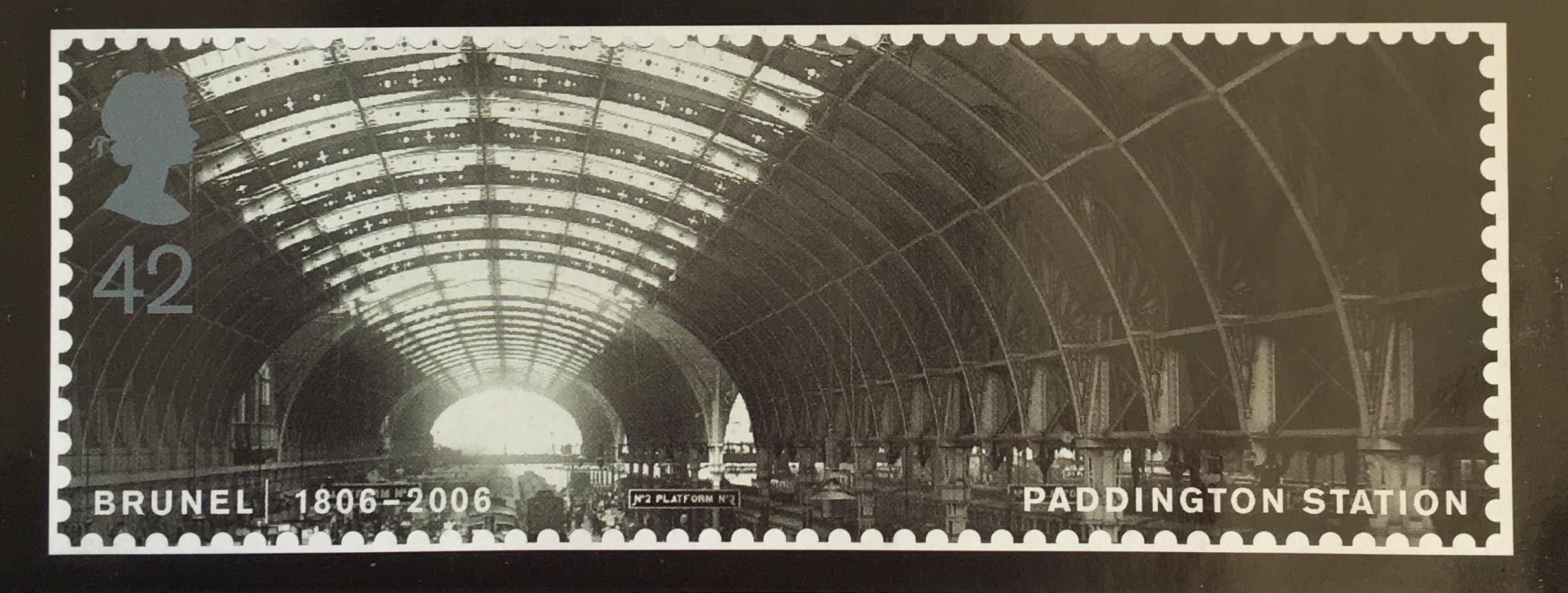

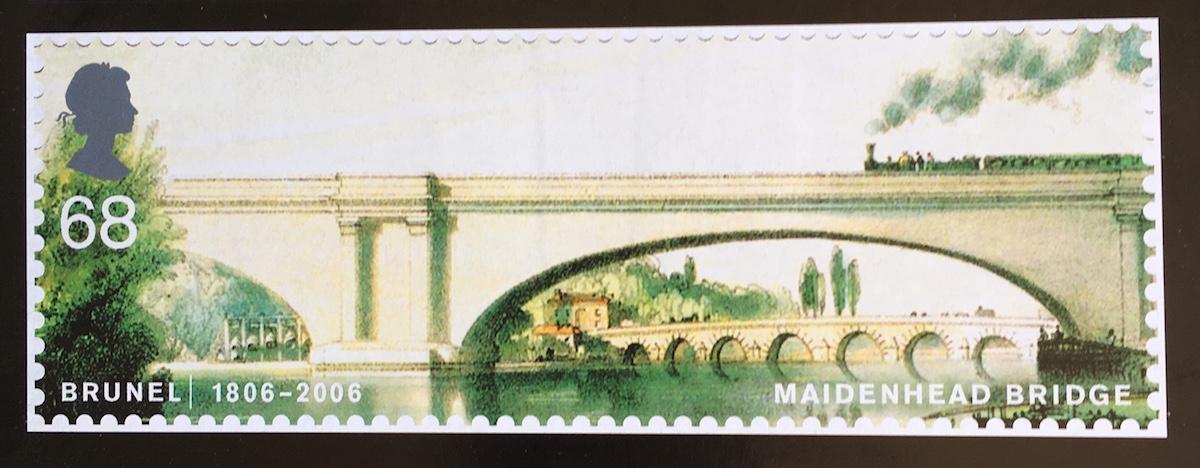

Conversely at the same time, in a rapidly industrialising Britain, a railway building phenomenon was taking place later to be known as “The Railway Mania”. One of many railway petitions put to Parliament was a bill for a railway linking the port of Bristol to London, which was duly passed on the 31st August 1835. The 118 mile long railway was to be given the grandiose title of the “Great Western Railway” (GWR), no doubt inspired by its young flamboyant Engineer, none other than Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859). Curiously the plans submitted to Parliament neglected to specify the rail gauge (the width between the rails), a ploy used by Brunel in pursuit of his “Big Idea”. Public railways hitherto had been laid down to the gauge of 4ft-8½in as stipulated by George Stephenson, this to Brunel’s innovative mind was far too narrow a gauge for high speed running and he thus envisaged a rail gauge of 7 feet, his so called Broad Gauge.* The railway would be opened in stages with the final link coming in 1841, with the completion of the two mile long tunnel under Box Hill (between Chippenham and Bath), allowing through running from London to Bristol at a breathtaking maximum speed of 60 mph, a mile a minute, faster than man had ever travelled. The Broad Gauge would be extended westwards in stages with Penzance in Cornwall being finally reached by 1867 when through running from Paddington was inaugurated on the 1st March of that year.

Commemorative stamp featuring the Box Tunnel

Alas it was all to no avail as a Royal Commission, as early as 1845, had reached the conclusion that only one gauge would be allowed, in order to avoid “a break of gauge” (where railways of a different gauge met). Members of the Royal Commission sat from the 6th August to the 18th December 1845 and heard evidence for and against each gauge and although the Broad Gauge was proven to be superior both economically and technically the narrower gauge had far more route mileage already built and it was this that swayed the argument in favour of the narrower gauge. In point of fact it was the Quartermaster-General of the Army who stressed the grave inconvenience of a break of gauge in the event of necessary troop movements should Britain go to War (which it did in 1853 in the Crimea) that became the real clincher. The Royal Commission not only recommended to standardise on the 4ft-8½in gauge but also to compel the Great Western and its broad gauge allies to convert their lines forthwith.

Commemorative stamp featuring the Royal Albert Bridge

The broad gauge stood condemned but the axe would not fall there and then, as the Railway Regulation (Gauge) Act which gained Royal Assent on the 18th August 1846 did not abolish the broad gauge but instead limited its expansion to South Wales and the south west of England. This isolation would eventually lead to the ending of the broad gauge but it would be a very long time coming, as it was on Friday 20th May 1892 that the last Broad Gauge express left Paddington at 10:15am, its destination Penzance. On the following Monday, the 23rd, the first narrow gauge express left for the West Country after a week-end of track conversion, which in itself was a triumph of organisation and coordination.

Commemorative stamp featuring Paddington Station

Even though Brunel’s Broad Gauge was technically superior it was deemed to be a failure on the basis of its smaller “Market Share”, a modern day analogy would be the case of the competition between the two makes of video cassette recorder, “VHS” versus “Betamax”, the latter was technically superior but lost out in a most bizarre fashion owing to it not being able to record in full an American Football game complete with “Time Outs” and advertising endorsements (which could take longer than 3 hours).

The British narrow gauge of 4ft-8½in (1435mm) became the world “Standard Gauge” and gauges wider than this were classified as “Broad” and those narrower as “Narrow”, thus India, Iberia and South America would settle for broad gauge railways of 5ft-6in (1676mm) and South Africa, New Zealand, Japan, Queensland and Western Australia would have narrow gauge railways of 3ft-6in (1067mm). Of course there are many more gauges one could mention suffice to say that as a rule the more mountainous the terrain a railway has to cross the narrower the chosen gauge becomes, although another reason is that where countries could not afford to build to the main line standards of Europe and America they reduced their capital costs by scaling down the gauge and thus the size of their infrastructure.

If you remember the question before my digression: i.e. why did the docks of Table Bay have a 7 foot gauge railway? The answer is given courtesy of the website “Soul of A Railway” - System 1, Part 16 - Table Bay Harbour” (Ref. 6), which states that “the Harbour Board made the surprising decision to install a 7 foot gauge railway to progress the harbour construction”.

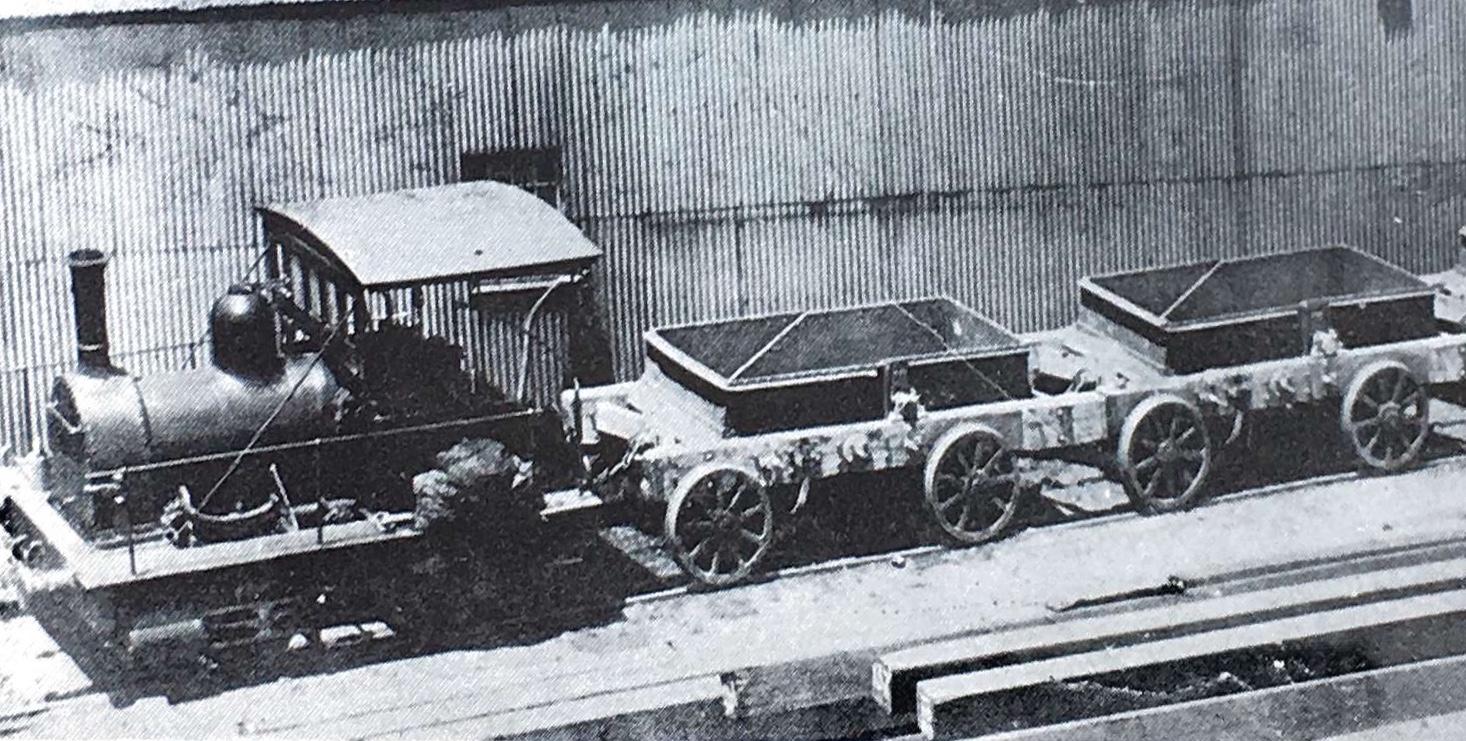

The Fletcher, Jennings 7ft gauge locomotive for Table Bay harbour (Steam Locomotives of South African Railways – Volume 2, 1910-1955)

Second 7ft gauge locomotive for Table Bay harbour (Steam Locomotives of South African Railways – Volume 2, 1910-1955)

My take on it is that large capacity wagons were required to convey rock from the quarry to construct a breakwater and the broad gauge was an acceptable temporary solution to the problem of bulk materials handling, certainly not what Brunel had in mind when he planned his GWR (God’s Wonderful Railway).

* The author is aware of the 1/4 inch increase.

References and further reading:

- “Early railways at the Cape” by Jose Burman, published by Human & Rousseau, 1984.

- “Great Western Railway 175 Glorious Years” by Robin Jones, a Heritage Railway publication, 2010.

- “Steam Railways in Retrospect” by O.S. Nock, published by A & C Black, 1966.

- “The Cape Gauge – Ox wagon to Iron Horse” by Peter Ball, Heritage Portal.

- “Steam Locomotives of South African Railways – Volume 2, 1910-1955” by Frank Holland, published by Purnell, 1972.

- “Soul of A Railway – System 1 Part 16 – Table Bay Harbour” by Les Pivnic. (Soul of A Railway – Google Sites)

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.