Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

“The cemetery is the ghost of Roodepoort West. It is the last vision of the vibrant African location that once stood where the suburban houses now stand. Like a ghost, the cemetery continues to haunt the people, now living miles away in Dobsonville, who remember its past." - Michelle Hay.

This paper explores the layered meanings attached to Juliwe Cemetery, and efforts to recognise the significance of the site. As the only piece of the old Roodepoort West Location to be spared demolition, the cemetery became a centre-piece of a story of forced removals which for over 50 years remained unknown to the wider public, and which has only recently begun to be acknowledged in the public sphere.

When the rest of the old African location of Roodepoort West was destroyed from 1956-1967, the cemetery remained after threats of protest caused by its proposed destruction of the graves persuaded the authorities to leave it alone. With the rest of the location having been erased and covered over by a whites-only township, the cemetery remains as evidence of a community which was made to move to Dobsonville.

At a Heritage Month event hosted by the City of Johannesburg in 2017, ex-residents returned to the old location cemetery which is all that remains of Roodepoort West Township, called Juliwe by its people. In an emotional ceremony, a memorial was inaugurated to acknowledge and interpret this black cemetery, now surrounded on all sides by the suburb of Horizon View.

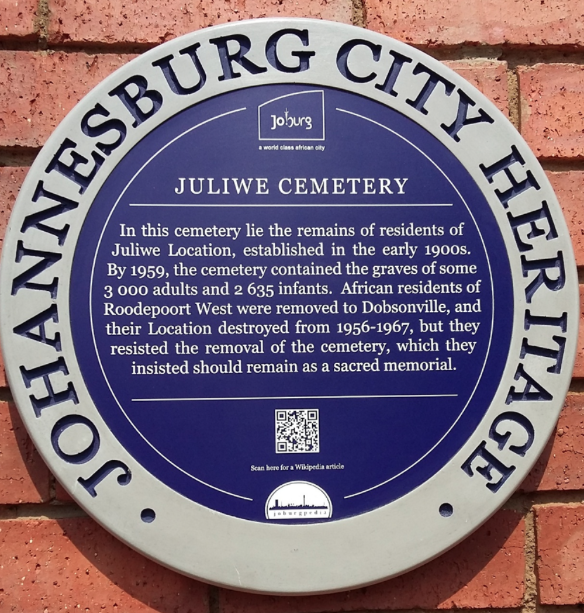

Near the edge of the cemetery, a blue heritage plaque was unveiled by the City’s Mayoral Committee Member for Community Development, Clr. Nonhlanhla Sifuma, giving a mark of recognition from the City to a community whose dead had most often been treated with official disregard and neglect.

The City of Johannesburg heritage plaque carries the inscription:

In this cemetery lie the remains of residents of Juliwe Location, established in the early 1900s. By 1959, the cemetery contained the graves of some 3 000 adults and 2 635 infants. African residents of Roodepoort West were removed to Dobsonville, and their location destroyed from 1956-1967, but they resisted the removal of the cemetery, which they insisted should remain as a sacred memorial.

Blue Plaque (City of Joburg)

Buses were laid on to bring senior citizens from Dobsonville to the unveiling at Juliwe Cemetery held in the early morning. After the official ceremony at the grave-site, hundreds of community members gathered at the Kopanong Community Hall in Dobsonville for a day-long session of community dialogues, with reminiscences of past lives in Juliwe, and the early days starting over in Dobsonville.

The gathering at Juliwe Cemetery and at the hall in Dobsonville, marked a first step of according public recognition to a long-neglected story of displacement and loss from the annals of apartheid-era forced removals. It came about through a City initiative, responding to a long quest by a group of Dobsonville residents, organised under the banner of The Greater Dobsonville Heritage Foundation, to make their history known. At the heart of these efforts was a desire to raise a memorial at the site of the old location cemetery.

The story of Juliwe was again brought into public space a year later, with an exhibition launched at the Roodepoort Museum on 24 September 2018, Heritage Day. Displays featured personal photographs and documents from Dobsonville residents reflecting disrupted lives. Images show people first going about their activities in in Juliwe and later re-establishing themselves in Dobsonville.

A view of the Dobsonville History Exhibition at the Roodepoort Museum

The new museum exhibitions and cemetery monument form part of the Greater Dobsonville History Project, which began as a community initiative, led by The Greater Dobsonville Heritage Foundation, to recover and make known the history of Roodepoort West Location.

The public history elements have drawn on an oral history project, based at the Wits History Workshop, and a more recent focus on the development of a community archive. With its various strands, the project involves the Roodepoort Museum, the City’s Heritage Unit, and the Wits History Workshop, engaging with community groups from Dobsonville.

A quest for recognition by ex-residents began with a land restitution claim in 1998-2000. The potent symbolism of the old cemetery made it a focal point for the land claim.

The Greater Dobsonville Heritage Foundation developed out of applications for Land Claims, as a group of former residents of Juliwe trying to help claimants find information. This began as a committee was formed in Dobsonville by a group former stand-holders, and children of stand-holders, of Roodepoort West. The claimants achieved some success, and each claimant received R 60 000.00 in compensation.

These land claims came at a time when little was known about Roodepoort West or Dobsonville, there were no studies done, and the story of Juliwe hardly came up at all in the literature. The claimants looked for points of support for recording the linked history of Roodepoort West and Dobsonville. To this end, they sought help from the Arts, Culture and Heritage Directorate City of Johannesburg, who also linked them to the Wits History Workshop.

In the course of this project, efforts by community members to recapture lost lives led to locally-produced histories, community dialogues, museum displays and the development of memorials. All of these activities and expressions - from producing local histories, to exhibitions and memorials - are ways re-capturing, sharing and sustaining memory.

By 2007, a ground-breaking study was produced by the Wits History Workshop, with oral histories revealing many aspects of location life, although this has remained unpublished. A prominent issue which came to the fore, in both community narratives and official documents, was about the fate of the Roodepoort West Cemetery.

The roots of the Roodepoort West location go back to the early 1900s when an informal location for African mine labourers was taken over by the Town Council, and soon became known as Juliwe. Like many old African townships, Juliwe was predominantly poor, with many living in slum-like conditions, with no electricity, overflowing latrines, and dirt roads. By the 1940s parts of the location were increasingly overcrowded.

Despite the hardships, Juliwe is remembered as a vibrant place, with a strong sense of community. The strong desire of ex-residents to record their history and re-ignite fading memories bears testimony to the attachment people felt for their historic home, and the sadness with which they look back at the loss of it.

Aerial photograph of Juliwe Township, with the cemetery in the top left-hand corner (Roodepoort Museum)

Early on in the life of Juliwe, the cemetery was located on the west side of the location, surrounded by gum trees, with a communal cattle kraal located nearby. As early as 1929, The Advisory Board expressed anxiety about the shortage of burial space in the cemetery, and reminded Council that it had previously consented to the use of this space as a public burial ground.

Around the decade between 1936 and 1946, the African population of Roodepoort was increasing fast, at a time when the white population was growing in even faster measure. The massive economic and demographic upsurge in Roodepoort, marked by a doubling of the white population between1937 and 1947, brought increasing pressure to dislodge African communities to make way for the growth in white settlement.

The financial opportunities of white expansion were not lost on the registered owner of the land on which the African location was established in 1907, the Horizon Development Company. So it was that the company proposed that a white township (later named Horizon View) be established on the site. With the backing of the Local Authority, this solidified into a scheme to remove African residents to the distant township of Dobsonville.

When Roodepoort West was declared a ‘block spot, to make way for the fast-expanding white suburbs of Roodepoort, the reaction of African residents was somewhat ambivalent. As Hay explains, many residents looked forward to better housing in more spacious surroundings:

… the general mood was sadness tempered with expectation. Dobsonville offered something that many residents, particularly lodgers, of Roodepoort West could only dream of: running water, one tap per house, one latrine per house, brick walls, four rooms, a little garden.

The first phase of the removals began in 1956, and by 1967 the whole of Juliwe Township was destroyed, with the sole exception of the cemetery. While removals from Roodepoort West took place without organised or widespread resistance, there was one issue which had the potential for conflict which was the intended removal of the cemetery. In negotiations over the removals, the future of the cemetery became the most contested issue, with African residents being determined in resisting the removal of the cemetery.

Most adamant that the cemetery had to go was the Horizon Development Company. The company wanted to lay out a white township (Horizon View) on the land on which the old location stood, and insisted that the location cemetery was a ‘discouraging factor” which should be removed.

In 1956 the Town Council began negotiations with the Horizon Development Company over the removal of the old location, and the future of the old location cemetery. These negotiations dragged on for several years, since from 1958 onwards there was a clash of interests between the Town Council, the Horizon Development Company, and African residents whose dead were treated with such disregard.

In 1958 the Town Council moved to close the cemetery, and rumours reached Juliwe residents about the proposed destruction of their burial-site, and the planned exhumation of the human remains, which would then be re-interred in a mass grave.

The impassioned response of African residents was conveyed in a memorandum from the Roodepoort Advisory Board, towards the end of 1958. Writing to the Town Clerk, Mr Mashao, the Chairman of the Advisory Board, warned:

The residents feel very strongly about the removal of the cemetery. The cemetery has been in existence for a considerable time. Generations, forebears of the residents, rest in that cemetery, and the cemetery has come to be regarded as a most sacred institution among residents. The veneration with which the residents regard their ‘DEAD’ [Their Emphasis] is common knowledge. The residents, therefore, feel that a great wrong and injustice would be committed if this sacred institution would be desecrated …

How do we account for this sense of horror aroused in particular by the threatened bulldozing and desecration of graves? At a time when the impending destruction of peoples’ living spaces – including homes, schools and churches - was in a sense more easily accepted, why is it that the cemetery, more than anywhere else, came to be held up by the embattled community as “a most sacred institution?”

Death, in most societies, reveals deeply-held community values. The case of Juliwe was no exception, and strong emotions were stirred, influenced an interplay of Christian faith and African ancestral beliefs.

The cemetery played a great role in cultural, community and religious life, and was the focus of much ritual activity – a place where both Christian and African ancestral rites were carried out. Funerals were occasions for social solidarity, attended by both churchgoers and traditionally minded people. Ministers from different churches would come and all church denominations would unite.

As pointed out by Hay, the heated response in relation to the cemetery has in some measure to do with the continuing role of ancestral beliefs, and the importance of the cemetery as a place of communication with the ancestors. Particularly in times of suffering and crisis, many African people turn to the ancestors for comfort, guidance and protection. Nonetheless, ancestor beliefs are varied and complex and often defy easy generalisations. The majority of community members coming from Roodepoort West were members of various Christian Churches, and some reject belief in ancestors as contrary to Christianity.

As the place of final resting and the abode of the ancestors, the cemetery was viewed as almost sacred ground. So when rumours began to spread among the community that their cemetery had been sold off and people could no longer visit, there was much anxiety and indignation.

In their Memorandum to the Town Council, the Advisory Board requested assurances to allay the fears of residents. They asked:

- That the cemetery shall be properly enclosed, and left intact as a sacred memorial institution

- That, in the event of the removal of the residents from the Location, the residents shall always be accorded the right to enter the cemetery, and pay homage to their dead.

- That the ground of the cemetery shall not at any time in the future be converted to other use.

The final paragraph of the memorandum carried sounded a warning, which would have been noted by the Town Clerk as the official responsible for the orderly removal of the Old Location. The memorandum ended with the impassioned words:

… we would respectfully urge that unless such assurance is given by the Council, a grave and permanent sense of injustice and wrong would be bred, that would pass from generation to generation and would never be forgotten.

The Roodepoort Council took the memorandum seriously, and sent it to the Horizon Development Company in March 1959, for them to consider. Still, the company remained unmoved by the concerns of the residents, insisting that the cemetery be removed.

The Council was more concerned to maintain the “goodwill” of African residents, and ensure the smooth and unhindered removal of the location. After also considering the high cost that would be involved in doing away with the cemetery, the Council decided that there would be no such removal. This shift shows the flexibility exercised by the Town Council of Roodepoort for defusing what could have become a serious threat.

After more argument from the Company over costs and details, by 1961 the developer finally relented, agreeing with the Council that the cemetery would not be removed. As an alternative to the removal, the graves would be levelled and numbered markers would be provided at each grave. The cemetery would be grassed, a wall would be built around it, and the area would be maintained by the Council.

Objections by residents succeeded in preventing the removal of the cemetery, although the outcome carried significant loss and bitterness. The graves of the old cemetery were not bull-dozed, but former residents relocated to far-flung Dobsonville would struggle to visit the graves of their ancestors. Together with the physical distance between the old cemetery and the new location, the Group Areas Act presented another barrier to visiting the cemetery.

After Juliwe location was removed, actions taken at the cemetery by the Town Council were profoundly disrespectful to ex-residents and their dead. Graves were flattened, and numbered pegs used to identify individual graves were removed. The effect was to depersonalise the cemetery, making it increasingly difficult to locate where individuals were buried. Further indignities came from vandals knocking over tombstones and leaving piles of refuse.

Aerial photograph taken after the demolition of Juliwe Township

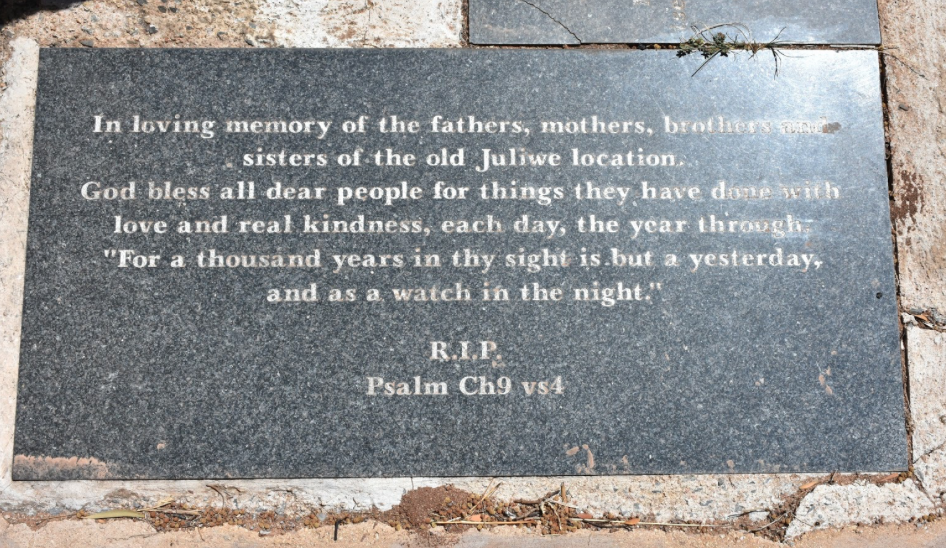

By the late 1990s, the group advancing last claims pushed also for a memorial to mark the cemetery as a site of deserving of respect. By 2000, a simple, small-scale stone memorial was erected, standing on a granite plaque. The inscription is engraved in English, Tswana and Xhosa with the message:

In loving memory of the fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters of the old Juliwe location. God bless all dear people for things they have done with love and real kindness, each day, the year through. ‘For a thousand years in thy sight is but a yesterday and as a watch in the night. RIP Psalm Ch9 vs 4.

The small-scale stone memorial (City of Joburg)

The small stone panel generated from the community initiative was later felt inadequate by ex-residents, who called for a more substantial intervention from the City of Johannesburg. The introduction of the City’s blue heritage plaque in 2017, brought greater presence and visibility to the memorialisation of the cemetery. The community memorial was re-mounted alongside the City plaque, which is raised on a brick column.

A blue heritage plaque awarded by the City of Johannesburg stands alongside a community memorial. (City of Joburg)

For ex-residents of Juliwe, the maintenance and dignity of the cemetery remained an ongoing concern during the apartheid period, and this continues to the present. Today, community members complain of poor maintenance, with tall grass being cut only infrequently during the rainy season. The wall which enclosed the cemetery has long since come down, and many people use a well-worn walk across the cut across the cemetery, trampling over graves as they go.

Yet in a quiet corner of the cemetery, some sense of dignity has been restored with a memorial giving recognition to the defiance that recued the cemetery, and remembering past injustices which refuse to be buried.

About the author: Eric Itzkin is Deputy Director: Immovable Heritage in the City of Johannesburg. This article is based on a paper he presented for the Falling Monuments, Reluctant Ruins Colloquium held at Wits during November 2018.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.