Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In the first installment of the series on the history of Southern African railways, Peter Ball described some of the earliest railways in the country and the extension of a number of lines into the interior. In this article he looks at the fascinating politics and economics of the 'Race for the Rand'.

Johannesburg was literally and figuratively built on Gold, the discovery of which in 1886 was to change the entire economic and financial structure of South Africa. The inconvenient truth for Britain was that the Rand Goldfields were in another country, to be exact the Transvaal Republic (a.k.a. South African Republic), which had regained its independence, after the Battle of Majuba Hill, Natal on the 27th February 1881.

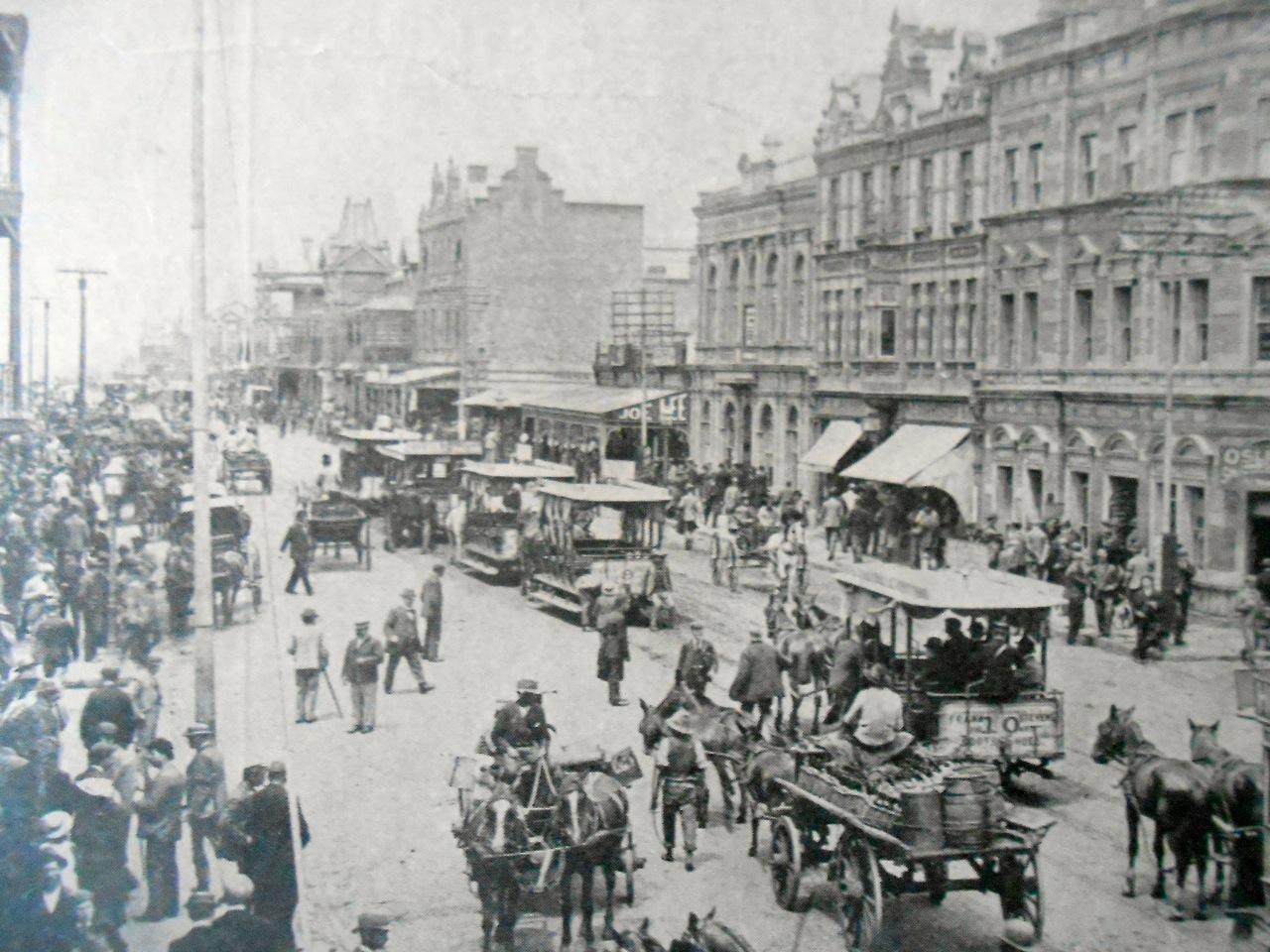

Johannesburg, springing up as it did in the midst of a rural, land locked Boer republic, was situated 345 miles (555 km) inland from the nearest harbour (Delagoa Bay); it had grown, within four years, from a mining camp into a boom town (second only in size to Cape Town) and urgently needed good communications to develop further.

Johannesburg in the early 1890s (Seventy Golden Years, Johannesburg City Council)

The Race to the Rand was a three (iron) horse race over many physical and political hurdles and the riders wore the colours of the Cape, Natal and the Transvaal. At the “Off” they started from different points of the compass and the Transvaal was tipped to win, as the Cape and Natal were handicapped under the rules of the race. As to the eventual winner time would tell.

Before getting down to telling the story of the Race to the Rand, it would be wise to give a brief overview of the period from 1850 to 1900; a time when the European powers were vying for colonies in Africa, in what became known as the “Scramble for Africa”. In the early to mid nineteenth century the European settlers at the Cape were exploring the interior of southern Africa, very much as the Americans did when they went “West”, through the Cumberland Gap. These pioneers were of Dutch descent and were leaving the boundaries of the Cape Colony to start a new life beyond the Orange River and away from British rule. They were self reliant farmers (boers) that wished to lead a pastoral life and practice their Calvinist religion without interference. They came to be known as the “Voortrekkers” and their exodus, the “Great Trek” of 1837.

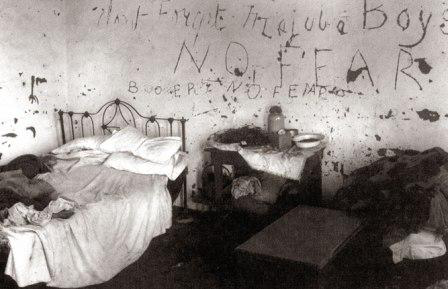

Britain considered itself to be the paramount power in the region but was prepared to allow the two Boer republics, the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, their independence. The former, was given independence by the signing of the Sand River Convention of 1852 and the latter by the signing of the Bloemfontein Convention of 1854. Notwithstanding these agreements, Britain saw fit to take over the Transvaal in 1877, which in turn rebelled to defeat the British at Majuba (1881) and thereafter regain its independence, by the signing of the Pretoria Convention. This sets the scene for the years up to 1900 which are remembered for the antipathy between Boer and Brit.

'Don't forget Majuba Boys' - Graffiti left by the Boers for the British during the South African War (The Boer War, Thomas Packenham)

Cecil John Rhodes, an Englishman who had come to Africa for the benefit of his health and made a fortune in diamond mining, became the mover and shaker of the late nineteenth century. He was a man on a mission and he wished to use his vast wealth to become an empire builder for his queen and country. His only stumbling block was to be the newly enriched Transvaal, led by its implacable president, Paul Kruger. Rhodes wore many hats and was at the same time the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, Head of De Beers Consolidated, Head of Goldfields and Head of the British South Africa Company. With all his portfolios he wielded immense power and used it to take over large tracts of land to the west and north of the borders of the Transvaal, in what was to be colonization by the Cape Colony on behalf of the British Empire.

Paul Kruger was well aware of the aspirations of the Cape Colony and pursued his policy of an independent route to the sea (a “Voortrekker” ideal). In furtherance of this aim he was determined to block the railway lines coming up from the Cape and Natal, certainly until such time that his own main line from Pretoria to Delagoa Bay (the present day Maputo) was completed.

The railway concession for the Delagoa Bay line was in the hands of a Dutch company, the “Nederlandsche Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg Maatschappij” (NZASM), which was established in Amsterdam, Holland on 21st June 1887; they were responsible for the project management of the construction of the line and, once it was built, the operating of it. There was a time lag before construction could start owing to difficulties arising over the border in Mozambique, but once these were resolved work on the line commenced on the 1st November 1889, working westwards from the border. The Portuguese administration was responsible for the line from the border eastwards to the sea.

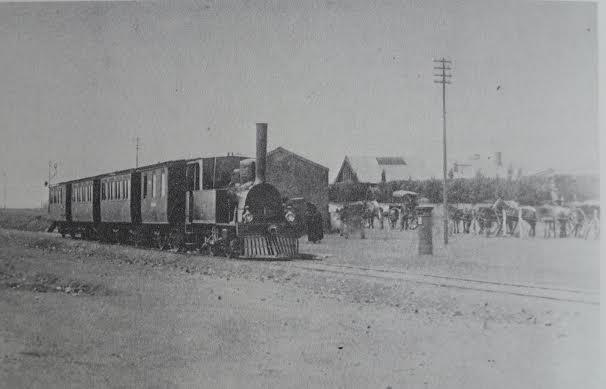

The delay in starting the main line was to be a blessing in disguise as it gave the NZASM the opportunity to build and operate the first public railway line in the Transvaal; a line that would run in an east to west direction, following the Main Reef, between Boksburg and Johannesburg. It was built to serve the pressing needs of the Rand mines and was given the nickname the “Rand Tram” even though it was a proper railway using the Cape Gauge. The line opened to passengers and freight, on the 17th March 1890 with extensions the following year to Springs (to the east) and Krugersdorp (to the west). The NZASM and their contractors had gained invaluable experience, which would serve them well when it came to the construction of the Delagoa Bay line.

The Rand Tram (Seventy Golden Years)

Meanwhile the Cape Colony and Natal, were both eager to get their share of the burgeoning trade generated by the mines on the Rand, which had become, in a mere five years, the economic hub of the region. Two railway camps emerged, which ironically, were based on financial considerations rather than brotherly love. In the one camp were the Cape and Orange Free State (O.F.S.) and in the other camp were Natal and Transvaal. As early as 1887, both camps had realised the necessity of pushing on from the existing railheads towards the Transvaal border.

The Cape Government Railways (CGR) began work on the extension of their Midland Line (the line coming up from Port Elizabeth) onward from Naauwpoort Junction, with the objective of reaching Bloemfontein by Christmas 1890. The line passed through Colesberg and then crossed the Orange River (into the O.F.S.) at Norvals Pont, progressing on to Springfield (the future junction with the CGR Eastern Line) before reaching Bloemfontein (capital of the O.F.S.). The level plains of the Free State were ideal for railway building and the CGR raced north to reach Viljoensdrif, on the banks of the Vaal River, by late 1891.

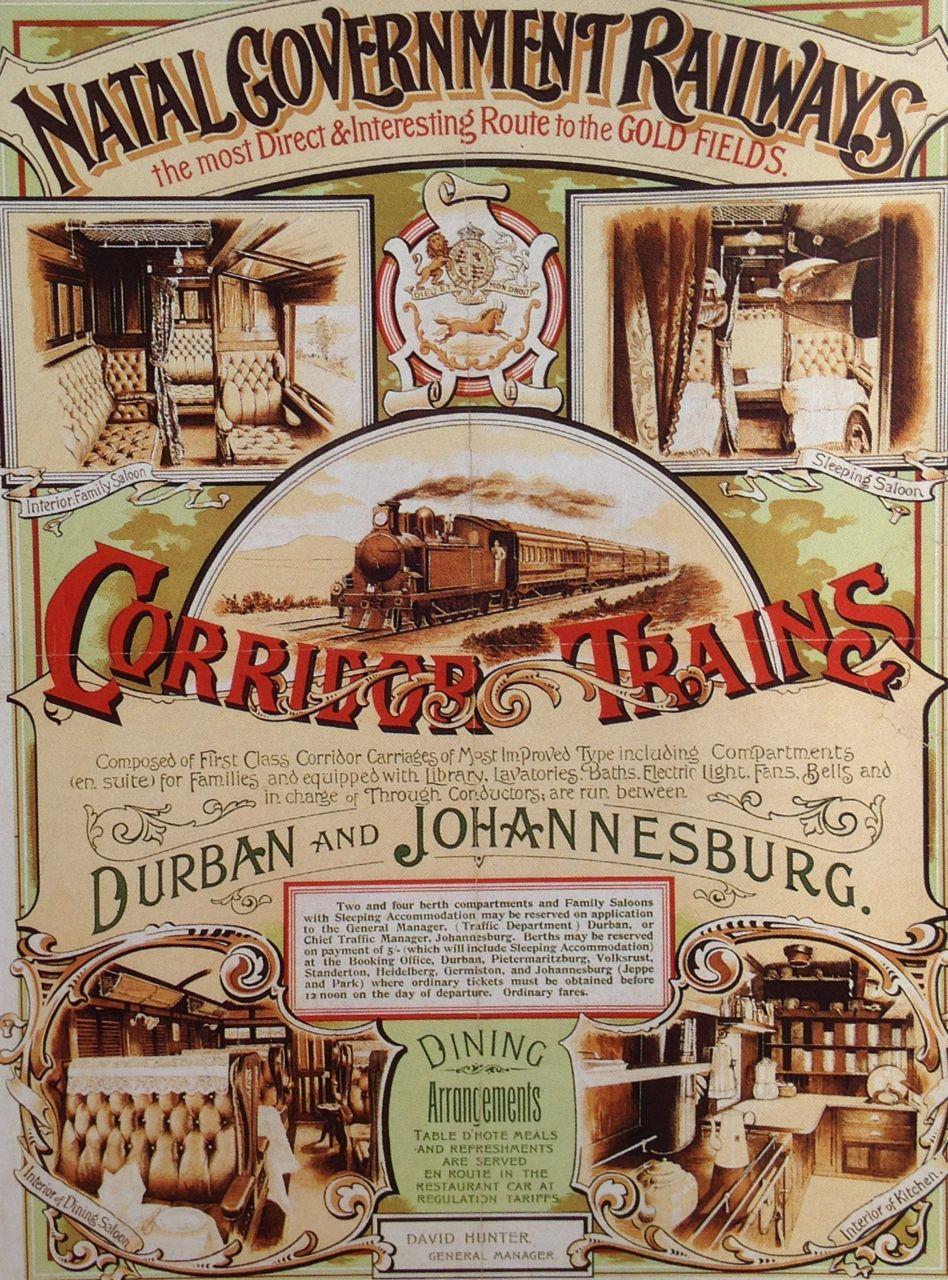

The Natal Government Railways (NGR) had reached Ladymith by 21st June 1886, which was very soon after the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand. The railway line up from Durban, had begun in 1875, with the first aim to reach the colonial capital, Pietermaritzburg (1st Dec 1880) and thence onward to Ladysmith, where the trade routes from the Free State and the Transvaal converged. Until 1886 the railway had been a drain on the colony’s finances but with the discovery of gold “up country” that was about to change as traffic volumes increased dramatically to and from the Rand. The extension of the railway became the priority and would go forward on two fronts, the main line to Charlestown (7th April 1891), close to Volksrust on the Transvaal border and a branch to Van Reenen and Harrismith, O.F.S. (13th July 1892). The former would tap into the coal deposits on the way, at Glencoe and Dundee and the latter was built as an alternative route north - a case of hedging one’s bets.

Old advert for Natal Government Railways (Transnet Archives)

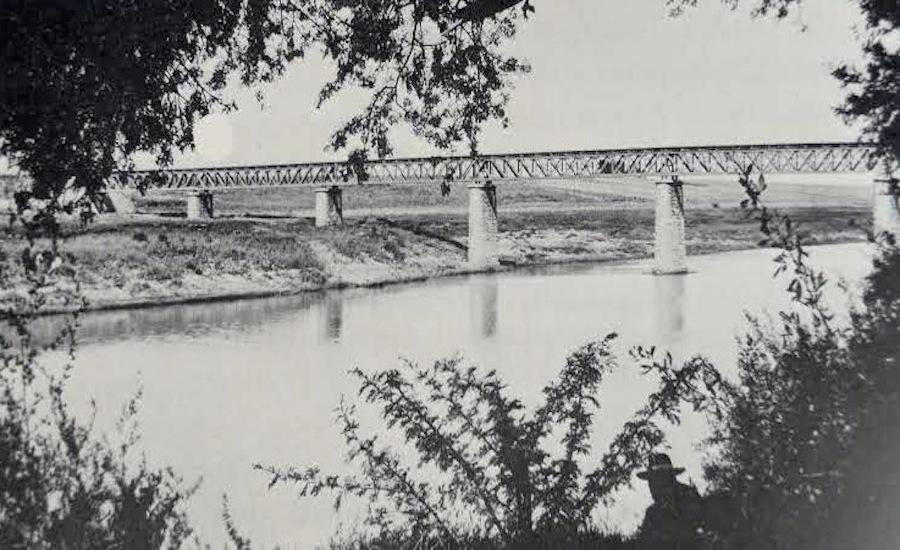

The political pressure from inside and outside of the Transvaal began mounting from 1889 onwards and, when it was realised that the Delagoa Bay line was unlikely to be finished before the end of 1894, Paul Kruger let it be known that as far as he was concerned the CGR could be extended to the Vaal River. That was not his only concession as he also persuaded the “Volksraad” to sanction a railway line from Pretoria to the Vaal River via Johannesburg, which would meet the CGR at the Vereeniging Bridge. This turn of affairs was brought about by the “realpolitik” of the time, which was the economic dominance of Johannesburg and its urgent transport needs.

Thus the CGR became the first railway to provide the vital link between the coastal ports and the Rand and the first through train arrived from Cape Town at Park Station, Johannesburg on 15th September 1892 (a two and a half day journey).

The story continues with the ZSASM successfully completing the Delagoa Bay Line (Eastern Line) by November 1894 and opening it to traffic on New Year’s Day 1895. Concurrently work was progressing with the line between the Rand and the Natal border (South Eastern Line) to link up with the NGR at Volksrust. This was to be a combined effort between the NZASM and the NGR and the line opened to traffic on the 2nd January 1896, thereby completing the last trunk route to the Rand.

All the trunk routes to the Rand were laid to the Cape Gauge (3’-6”), thus eliminating the “break of gauge” which would require time wasting transfer of goods from one wagon to another. The five major ports; which were (going clockwise) Delagoa Bay (Maputo), Durban, East London, Port Elizabeth and Cape Town were now part of a railway system which radiated from the Rand and can be likened to a hand, where the railway lines are the fingers and thumb and the Rand is the palm.

References

- “Early Railways of the Cape” by Jose Burman.

- “The Natal Main Line Story” by Heinie Heydenrych Bruno Martin.

- “NZASM 100 - The Buildings, Steam Engines and Structures” by R C De Jong, G M Van der Waal and D H Heydenrych.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.