Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Dikgang Moseneke's (judge and a former deputy Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court) schooling fate was preordained. At the beginning of 1961, just after he had turned thirteen, he stepped up to the plate to be the third generation of family devotees to attend school at Kilnerton Training Institution. How could it be otherwise? Going to Kilnerton had been an immutable feature of the Moseneke family's heritage. Nearly sixty years earlier, his grandfather Samuel Dikgang Moseneke was nurtured there. After him, his two sons, Sydney and Rogers qualified as teachers at Kilnerton. Dikgang's father and two of his younger sisters, Moipone and Masikwane, also matriculated at Kilnerton.

Kilnerton Training Institution was established in 1886 at the foot of a small, idyllic, rocky hill on the farm Koedoespoort, near Silverton in Tshwane. The hill lent itself to being a natural Southern boundary of the farm. At the highest point of the hill stood a chapel with stone walls. The chapel was core to the ethos of the missionary institution. Between the railway line and the western perimeter of the farm ran a clear stream on a stony riverbed. Along the eastern border was the main road between the city centre and Silverton, a white working-class neighborhood, and further eastwards along the same road lay Mamelodi township.

Old photo of Kilnerton Chapel

Kilnerton was founded by the Reverend George Weavind. However, it was named after the Reverend John Kilner, secretary of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society of London, who raised the funds for its construction. At that time, all their clergy were drawn from Britain.

However, Kilner understood well that the evangelical task at hand could not be accomplished by foreign missionaries only. He supported the recruitment and training of an indigenous clergy. He saw the primary goal of the institution as being to provide high school education for African people and to train educators who would provide a pool for the recruitment and further training of ordained ministers and local preachers. When Kilnerton was established, indigenous people lived or later settled on nearby land that became known as Kilnerton village.

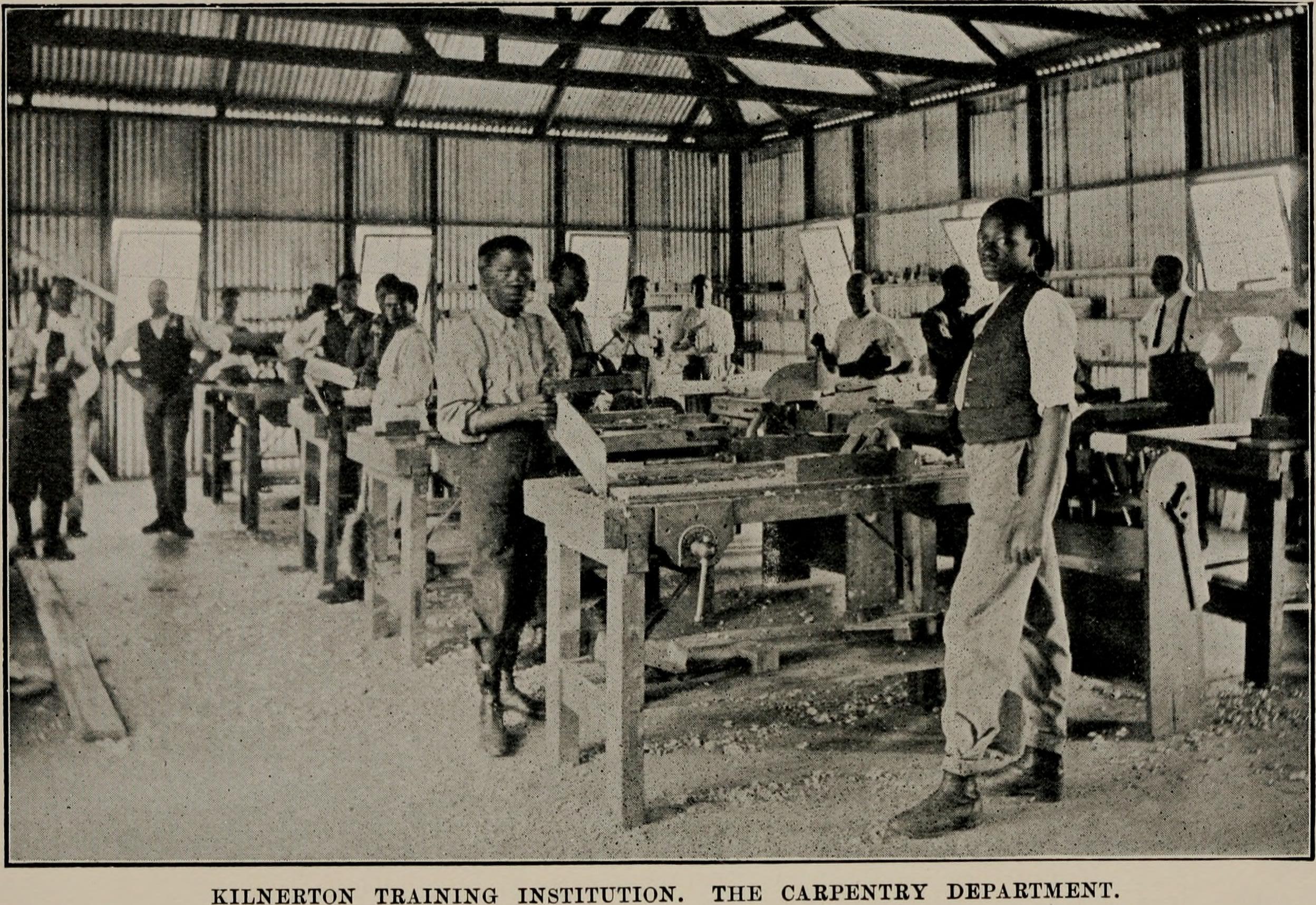

Besides the high school and teacher training college, Kilnerton served the community with two primary schools. This was also where learner teachers did their practical training. Added to that, the church ran a health clinic, special domestic science courses and an agricultural school.

In the face of what appeared to be obvious social benefits, many villagers and students converted to Christianity and joined the Methodist Church. The missionary purpose of the church was well served by its captivating spread of social offerings to the villagers and students. By the turn of the twentieth century, Judge Dikgang Moseneke's paternal grandfather Samuel Dikgang Moseneke, had completed his studies at Kilnerton Training Institution.

He would have known Reverend George Weavind, the founder and first principal of Kilnerton, who was succeeded by Reverend O Watkins in 1891. But more decidedly, he would have been aware of two very remarkable figures in the life of the newly established training institution, and the burgeoning Wesleyan Missionary Church in the Transvaal. They were the Reverend Mangena Mokone and Mr. Sefako Makgatho. Mangena Maake Mokone (1851-1936), an ordained minister of the Wesleyan Methodist Church, played a pivotal role in the founding of Kilnerton. Around 1885, he was George Weavind's right-hand man at the construction site of the institution.

His beginnings were humble. He left his home in Sekhukhune, Transvaal, for work on a sugar plantation in Natal. He was converted to Christianity in 1874, and immediately started theological studies in Pietermaritzburg. He worked by day and studied at a Wesleyan night school. At the end of a five-year study period, he was appointed to a preaching circuit of the Methodist Church in Natal.

In 1882, he was ordained and posted to Pretoria to give support to Reverend Weavind and Reverend Watkins at Kilnerton. Having been trained in carpentry, he is said to have built the school's fittings and also the chapel with his own hands. He was rightly one of the founding fathers of the institution. Soon thereafter he was posted to establish Wesleyan missions in the Waterberg in the then Northern Transvaal (Limpopo) and at Makapanstad (North-West).

Photo via Wikipedia

In 1892, Reverend Mangena Mokone returned to Pretoria as minister and principal of Kilnerton Training Institution. This was a remarkable feat, given the racial cleavage and profiling within the church at that time. Amongst his students was Sefako Makgatho, who was to become a distinguished teacher, writer, leader and freedom fighter, and the second national president of the African National Congress (ANC).

Sefako Mapogo Makgatho was born on 26 September 1861 at Ga-Mphahlele in Limpopo. The son of Kgosi Kgoruthle Makgato, his life straddled the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in nearly equal halves. He lived through a formative stage in South Africa's history and was not an idle bystander. He was blessed with leadership qualities, a good education and high levels of industry complemented by ample determination.

After having completed his schooling in Pretoria, in 1880, Makgatho enrolled at Kilnerton for a teacher training course. He was then under the tutelage of Reverend Mangena Mokone, who was the nominal head of Kilnerton. In 1882, Makgatho left South Africa to go and study education and theology at Middlesex, England. When he returned home in 1886, he joined the staff of Kilnerton as a teacher.

From the relatively youthful age of twenty-five, Makgatho kept his teaching job at Kilnerton for no less than twenty eventful years, until 1906. He must have been an extraordinary inspiration to his young charges. He would have noticed the changes wrought by the discovery of gold in Johannesburg and would have been angered by the grubby gold rush, as it spawned migrant workers, squalid urbanization and social decay for African migrant workers.

He left Kilnerton and formed a political resistance movement known as the African Political Union (APU). In 1962, when Moseneke went to Kilnerton, his father Samuel Moseneke, had been appointed to the prestigious multiracial staff of his alma-mater. He taught English and history to the matriculation classes, a position that was usually reserved for Scottish expatriate missionaries or local white teachers with a Scottish or Wesleyan descent. It was a distinct measure of personal achievement that he was as good as anyone else in his teaching craft.

Unlike his father, he did not get a scholarship. His father paid the boarding and tuition fees outright. He describes his beginnings at Kilnerton in his autobiography, My Own Liberator, "I remember him saying should I fail any year he would have nothing to do with me. I would have to turn myself over to the labour market. But he knew and I knew that failure was not on the cards.

Book Cover

Once the paperwork was done I quickly settled into boarding life. The initiation of msilas - freshers - was nothing as harsh as legend had it. Older boys sent you around on stupid errands. I opted to do them promptly and get out of harm's way. Happily, the school had by then banned all assault and any physical abuse of freshers".

As every dawn broke, like his forebears, he was out of his low dormitory bed well before the boarding house wake-up bell. The communal bathrooms were fitted with cold-water showers only. Decade after decade young boarders had to submit to a cold morning shower. His father must have. And so, in due course, so did he.

It was an austere start of the day. The dormitory minders must have believed that the boy' lithe bodies and souls would benefit from a stern start to the day. There was absolutely no point in pondering over the impending icy splash down their backs. The trick, many found, was to start bright and early and escape the later congestion of shivering bodies.

They would run mindlessly under the chilly spray, wrap up with a towel around their shoulders and dart back into the dormitory. Then they were set for the day. Moseneke's school uniform would be ready because the afternoon before he would have washed and ironed his white shirt and pressed his grey flannel pants in the communal laundry room.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, they wore khakhi shorts and pants because they had extramural activities. On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays the uniform changed to grey flannel pants and a white shirt with a school tie and a navy blazer. The left chest pocket of the blazer sported the school's blue and gold crest. The top inscription read, "Kilnerton Training Instituition" and the bottom of the crest displayed the motto Per ardua ad astra (Through hard work to the stars).

As he was a junior boarder, Moseneke was on a roster of dining hall servers. They were split to serve the senior and junior school dining halls. As the first rays of the fickle sun pierced through the clouds, breakfast was served. The resident boarding master was charged with that end of matters. The breakfast stood in sharp contrast to the spartan morning ablution.

The menu was basic but nourishing and ample, even for growing lads. By the time the rest of the boys fitted into the senior and junior dining halls, the wooden tables had been scrubbed and were fully laden. The servers, had to carry the breakfast from the kitchen to the dining halls. The food was the same, but the prestige of being served in the senior dining hall was beyond words for junior school.

Servers carted in tall alumininium jugs of coffee or tea and fresh milk. Generous helpings of oatmeal were served from large, well-used, beaten pots. Four slices of wholewheat bread with a lashing of peanut butter and jam, chased down with coffee got the day to a good start. The high school assembly bell rang at 7am.

The bell was housed in a tall clock tower, the centerpiece of the Victorian architecture of the senior high school building. The building backed onto the foot of a well-treed rocky kopje, and the classrooms ran off the tower towards the sides in a rectangular U-shape. They were built of light brown sandstone hewn from the kopje and their walls were punctuated by solid wood entrances and windows.

The red-brick clay tiles under the tower and verandah were beginning to fade as well they might after being trapped on by generations of boys. This was where the morning assembly was led. The principal stood beneath the tower and to his sides the teachers lined up. Assembly was a ritual never to be missed, except if one was indisposed.

"Classes lined up in neat rows" he relates, "and I would my take my place and stand, quietly and obediently, waiting for assembly to start. I could hear and feel my steady heartbeat. I sensed every breath I took. To this day, when I relish a moment of peace and quiet, my heartbeat and breath impose themselves upon my consciousness. Also, I was not unaware of my family's connection to that place of learning. My presence there was a privilege and a duty. I was one of only a few African children who would ever come to Kilnerton."

Moseneke did not bring to Kilnerton a virgin mind. He had lost his political innocence at Banareng Primary School, and later at Mboweni Primary School, both in his Atteridgeville hometown. His headmaster at Banareng, Mr Ramopo, had related to them the fables of James Emman Kwegyir Aggrey, a champion of African nationalism.

In 1960 he had been horrified by the Sharpeville corpses he had seen on the pages of the daily newspapers. His father kept dated copies of the New Age, a mouthpiece of the African National Congress (ANC), and Fighting Talk, which was produced by the South African Communist Party (SACP). He subscribed to the Africanist.

"I read and read", he explains. "Not all was well with our land, with the lives of African people. During my primary school days I had read Drum magazine. I read Can Themba, Lewis Nkosi and Nat Nakasa. The magazine ran features on the potato boycott of 1959, which was sparked off by the horrific use of prisoners to work on potato farms in Bethal. The Rand Daily Mail wrote about and displayed photos depicting prison conditions of black males."

Kilnerton's principal was Mr Nixon, and the chaplain was the Reverend Dugmore. At every morning assembly Mr Dugmore preached and prayed in isiXhosa perhaps better than in his native Scottish, which was difficult to follow. Then the students joined him in the rousing singing of the Lord's Prayer. Then they were quietly dismissed to start a day of relentless schooling. Only excellence, and nothing else would do.

After all, an admission to this great school was a singular privilege, all new students been warned. None dare mar its time-honoured reputation of yielding multiple passes with distinctions in the revered Joint Matriculation Board examinations. Although it was a co-ed high school, as a matter of tradition, the missionaries allowed nothing but strict separation between male and female residential facilities.

Girls always had the good sense never to come to the boys' hostel, but there was always a daring boy who would breach the perimeter of the girls' hostel, which was a little distance away. He would make an ill-fated dash through the beaming searchlights of the dormitory, hoping to reach his girlfriends' room. When he was caught, which usually happened, he was expelled summarily.

That, after all, was the first tutorial to all new boys. Even so, teenage testosterone got the better of some. Moseneke was not one of the boys to take the risk. For one thing he had night work - 'the algebraic formulae and geometry theorems took their toll on me', he recalls

Having applied himself throughout the day, he went to bed early and slept soundly. For another, he did not have the guts for a night operation, which called for military precision. And besides, he asked himself, how he would ever face his parents over an expulsion so dumb? Moreover, how would explain it to his mother? "I could imagine her question: what was I looking for at the girls' hostel at night?"

As for all public prohibitions everywhere, stories of brave breaches quickly made the rounds. Many heroes of the battle of the girls' hostel - mzana - surfaced. Boys who were known for their bravery would let it slip that they had spent an evening in a girl's hostel room. The stories were not verifiable, of course. Nobody was so foolish as to believe them, and they could not be proved to be true. Any possible witness ran the risk of expulsion.

So, with no risk of being caught out lying, fanciful claims of romantic nights flourished from amaromana, who were known to have girlfriends, and even from ngobias, who were high and dry and were yet to go out with a beautiful lady from campus.

On Sunday evenings Moseneke would walk up to the channel on the hill to hear the Reverend Dugmore deliver his perennial sermons. Like many early missionaries, he was remarkably proficient in the isiXhosa language.

At a point during the liturgy, in clear language, he would make known from the pulpit. "Let us sing Te Deum" - and he would continue in isiXhosa: "Siyakudumisa Thixo, siyakuvuma ukuba unguJehova, umhlaba wonke ubhedesha wena, oh Thixo ongungaphakade", meaning "We worship you God, we accept that you are Jehovah, the whole world praises you, oh eternal God." The chapel would break into a wondrous song of worship fortified by the best young male and female choir voices that the school had to offer.

It was only a matter of time before Moseneke submitted to the church confirmation classes. These were run by a young resident teacher, Stanley Mmutlanyane Mogoba, and supported by Reverend Dugmore. In time, and after a stint on Robben Island for political reasons, the same Stanley Mogoba was called to the Methodist church ministry. He rose up the ranks of the Wesleyan Methodist Church to become its presiding bishop in Southern Africa. To this day, retired as he should be, Mogoba still ministers to the spiritual needs of the villagers in his home village of Phokoane, in Limpopo.

What Moseneke did not know then, was that his stay at Kilnerton would coincide with its cowardly demise. In his second year, in 1962, the government forcibly shut down the instituition, and expropriated most of the scenic land on which it was located. Their pretext was that it was located on land which they had proclaimed to be for exclusive use or occupation by people classified as white.

"Like marauding barbarians “, he laments through the book, “the regime snuffed out that proud instituition of learning as one would a flickering candle, in the words of that timeless Miriam Makeba song about Sophiatown. Just like that, Kilnerton was gone. Thanks be to God, in 1994, only 32 years later, after much blood and tears and a little talking, we snuffed out the junta which exerted its power on us so heartlessly, but we couldn't bring back our school."

*Quotes in this article were transcribed from the subject's autobiography “My Own Liberator”

*Added information – Methodist-church.org.za Sahistory.org.za Robben-Island.org.za Tshwane.gov.za

Daluxolo Moloantoa is a freelance writer and journalist. After being awarded a scholarship by the Sowetan newspaper and Herdbuoys McCann-Erickson advertising agency he studied copywriting at the AAA School of Advertising in Johannesburg. After a brief period working in the advertising industry, he went on an exchange programme to England and studied for a Community Media Certificate with the Community Volunteer Service Media Clubhouse in Suffolk. He became an arts journalist with Ipswich-based youth magazine IP1 and began covering South African arts-based news for London-based South African publication The South African as well as Cape Town charity magazine The Big Issue. On his return to South Africa he became arts contributor to a number of local publications. In 2015 he won the Academic and Non-Fiction Association of South Africa (ANFASA) – Norwegian Foreign Fund Writers Award for his research project on missionary schools in South Africa. Click here to see more of his work.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.