Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

My parents were very intrepid when they were first married and often went to the Lowveld in their battered old car. They took hundreds of photographs. At some point, my Londoner father decided he wanted to buy a farm in the Lowveld, and after poring over the Farmer’s Weekly magazine for months, managed to find a small farm in the Elands River Valley in the Transvaal Lowveld, now the province of Mpumalanga. He was out of his depth immediately, an Engelsman amongst a very Afrikaner farming community. He tried unsuccessfully to make money from growing vegetables to supply a local canning factory, travelling almost every weekend from Johannesburg. He had to employ a farm manager to handle the actual farming activities and Mr Mostert was surly and unpleasant, but vegetables were actually grown, harvested and sent to the canning factory.

The farm manager, Mr Mostert, inspecting my father crop of peas, circa 1964.

My father eventually sold the farm to Mondi in the late 1960s, and the experiment in an agrarian life was not mentioned again. I recently decided to go through his photographs, about a thousand colour slides, looking for images of the farm. There weren’t many, about ten in all, probably attesting to how miserable he felt about this disastrous project of his.

Since then, South Africa has changed, with the democratic election in 1994 meaning that land ownership was no longer the preserve of white people and that a formal process was in place to provide for restitution of land rights to lawful claimants dispossessed of their land by the Natives Land Act of 1913. Also, in post-apartheid South Africa, there has been a huge movement of people as now anyone can choose where they need to live in order to find work and schools for their children. Many informal settlements have sprung up and there are hundreds of new places that were not on maps prior to 1994.

Recent trips to the Elands River Valley

When I did a trip to Nelspruit in 1998, travelling along the N4 route, I wasn’t totally sure where the farm was located in the newer landscape. It was hard to find what I remembered because the entire landscape was covered in Mondi plantations. There were so many trees that one could no longer see the house or fields. This made sense seeing that my father had sold up to Mondi. To orientate myself, I began to look out for the Elandshoek railway station. I almost missed it. It was looking very shabby. Then, travelling to the Kruger National Park in 2012, I found that the greater area around the station had changed greatly since my previous 1998 visit. The Elandshoek station itself was wholly derelict and seemed to be functioning as an informal settlement, with many people hanging about the station precinct and wood smoke drifting upwards.

Most of the plantations in the area were gone, and instead, many of the hills adjacent to the Ngodwana paper mill were covered with a large semi-formal settlement also called ‘Ngodwana’, providing housing for staff for one of the country’s largest paper mills.

Logs waiting to be loaded onto trains in the Lowveld in 2006 (Richard Taylor)

The Google Earth images below are more recent images of the farm my father used to own in the 1960s. In 2004, the farmhouse was still intact and the land appears cultivated. The N4 motorway had not yet been built. By 2021, the house was derelict, the fields overgrown and a huge informal settlement had sprung up across the river. It would be difficult to farm this small holding now under the conditions of rapid population increases in the area and the inevitable theft of crops, implements and fencing.

My fathers farm seen through the eyes of Google Earth 2004 image. The N4 motorway has not been built yet.

The same area in 2021. The farm house is derelict and the area across the Elands River is an informal urban sprawl. The N4 motorway had been built. The farm is no longer being worked and the ploughed field is overgrown. Google Earth image 2021.

Land ownership in the Elands River Valley

It would be interesting to understand the situation of land ownership in the Elands River Valley now – specifically who owns / owned the land where the informal settlements are developing? Is this now traditional land or was this once white farm land, restored through land claims, to local people? Are the new settlements considered a situation of land invasion? Interestingly, traditional leaders in Mpumalanga are themselves complaining about land invasions on their tribal land and the unlawful sale of such land to unsuspecting members of the public (Kunene 2012; Lubisi 2021).

What happened to the NZASM Elandshoek railway station?

When we visited the farm in the 1960s, we would pass the Elandshoek railway station and its various station buildings. As my father’s farm was only a few kilometres on from this station, it was an important landmark for us kids dozing on the backseat. Back then, the N4 had not been built, and there was a much smaller, quieter road. We never stopped at the railway station and we don’t have any photographs. Yet, when we travelled to my father’s farm in the 1960s, the Elandshoek station was a fully functioning station and it might have been fun for us kids to go in and watch out for trains.

Elandshoek Railway station building is of historic interest and played a role in the development of the Eastern Railway Line from Maputo (Delagoa Bay) to Pretoria (HIA 2014). On 2 November 1894, the line was completed and on 8 July 1895, was officially declared open by President Paul Kruger (HIA 2014). The line was built by the NZASM (Nederlandsche Zuid-Afrikaanche Spoorweg-Maatskappij) (HIA 2014). On the South African side, the line went via Komatipoort, Hectorspruit, Malelane, Kaapmuiden, Nelspruit, Elandshoek, Waterval Onder to Pretoria. The Elandshoek Station is a very good example of the typical station buildings built by NZASM. The main railway station building is a Victorian-style building built with dressed stone around 1896 (Richardson 2001).

The railway station functioned without interruption until 2001, after which all buildings were ransacked (Richardson 2001). A Heritage Impact Assessment of 2014 confirmed the derelict state of this small railway station. The main railway building is now severely neglected, but it could be restored to ‘its former glory’ (HIA 2014). Most of the useful items have been stripped, and of course, once the roof sheets are removed, the inner structure of the building is opened up to decay. The station is a declared Provincial Heritage site and is of Provincial significance (SAHRA ID 9/2/248/0002) although that status has not protected it at all.

The Original Elandshoek railway station circa 1896. (Atom reference number ZA 0375-P-P3602)

The derelict Elandshoek station today. The building was made of dressed stone and was in operation until 2001 after which it was vandalised. (Wessels 2020)

NZASM and the Five Arches Bridge

Between Waterval Onder and Waterval Boven (now Emgwenya), the new railway line had to be built that climbed up from the Elands River valley in the Lowveld to the eastern edge of the Highveld escarpment, on its way to Pretoria. To cope with the steep gradient, there was originally a rack-railway with a steep, curving tunnel over this stretch, but the route was later changed to a less severe gradient over a 14 km stretch with two tunnels. After this diversion, the old tunnel was used for road traffic until 1936, when the Elands Pass was built. The Five Arches Bridge was part of the original rack rail and opened to rail traffic in 1894. The rack rail ran along the bridge until it was no longer needed. The bridge was then converted to a road bridge and served as such for many years until the new tunnel was constructed next to the NZASM Tunnel, and the present N4 road was completed. The five arches bridge was proclaimed a historical monument in 1963 (Wikipedia).

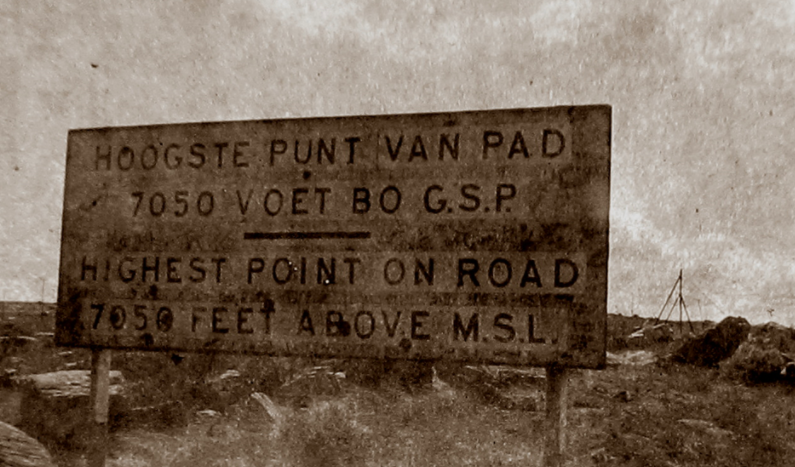

Highest point on the Lowveld escarpment photograph 1964

The Five Arches Bridge, now a heritage site, carried early rail traffic over the Dwaalheuwel Spruit, taking the train from the Elands River valley up to Waterval Boven.

The old tunnel on the left (The Heritage Portal)

Our Lowveld farm

The land parcel my father bought was a triangular piece of land going up into low hills, with a small spruit running down from the hills and which supplied the farm with fresh water. The flat area nearest the road was suitable for agriculture and, as mentioned, my father grew a variety of vegetables on this land. There was also a portion of the farm across the main road, sandwiched between the road and the Elands River, where the soil was very good. My father was made an offer by a neighbour to purchase this portion, and so the best part of the farm was lost.

The triangular-shaped farm with the flat area where crops were grown and the farm house only just visible, 1964.

The farm house. Only the kitchen was habitable at that stage (1964).

My mother at work in the kitchen of the house circa 1964. When we visited, we lived in the kitchen and never went into the other rooms. I wonder what happened to that iron stove.

A view looking north across the farm, circa 1964. The visible buildings belong to a neighbouring farmer. The land already looks damaged and overworked.

My mother chatting to a farm worker resident on the farm, circa 1964. My father acquired these workers when he bought the land.

Elands River Valley no longer a rural backwater

In the Elands River Valley, there have been huge social changes since the 1994 democratic election of South Africa. Now people can move freely and live wherever they need to, to find work and schools, and are not confined to homelands or farms. The changes in the Elands River Valley include expanding informal settlements next to the N4 and the loss of much of the vegetation cover around these settlements. Although there are still many areas under forestry plantations, many plantations have been logged and the land has begun to revert back to natural vegetation, albeit vegetation in a very impoverished condition. In general, the condition of the landscape is looking poor, and unless the land degradation process is reversed, this landscape will be unproductive for any form of subsistence or commercial farming in the future. Even my father’s farm, when viewed on Google Earth, shows signs of past poor land management and the vegetation appears worryingly threadbare.

New threats and old dangers

The Elands River Valley is no longer a quiet rural backwater. The N4 road is very busy and dangerous. After 2.00 pm each weekday there are hundreds of school children wending their way home. For these children and for other road users, the N4 and its heavy logging vehicles form a considerable hazard. Sometimes, the trucks carrying logs to the Ngodwana saw and paper mill travel in convoys of six or seven massive vehicles and they would be unstoppable in an emergency, for example if small kids were crossing the road.

Logging truck on the N4 through the Elands River Valley (Google Earth Street View 2017)

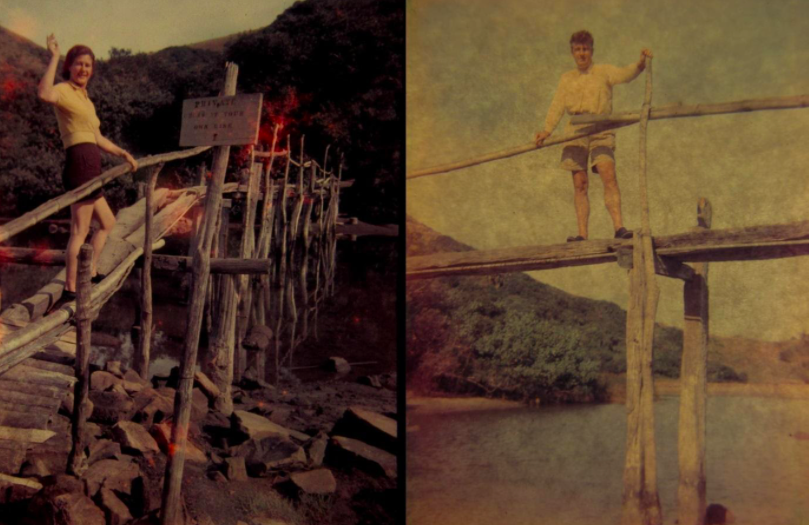

Also, the Elands River is a long-standing hazard for local people, with people crossing on an unsafe hand constructed foot bridge until a formal, concrete pedestrian bridge was built around 2015, requiring a heritage assessment (HIA 2014). My parents photographed each other on one of these rickety bridges in 1964. You would think in a timber-growing area, timber would have been generously provided to make a safe bridge for local people.

Jean and Victor on a rickety pedestrian bridge over the Elands River, circa 1964.

Land as heritage

Land is also part of heritage, as the pain of the land issue in South Africa attests. Land is strongly associated with culture and cultural identity, traditional values and a sense of belonging. Yet the National Heritage Resources Act (25 of 1999) does not cite land per se as a heritage asset. The National Estate includes those heritage resources of South Africa which are of special cultural value for the present community and for future generations, and which may be buildings, structures or equipment of cultural importance. They may also be places to which oral traditions are attached or which are associated with living heritage, historical settlements and townscapes. Also covered are landscapes and natural features of cultural significance (like sacred caves), as well as graves and burial sites. If they are part of some event or associated with a heritage features, areas must be declared as heritage landscapes or heritage sites, but land in general, even tribal land, is not a de facto heritage asset. And as we know, merely declaring something as a heritage asset does not protect it, and strong efforts still have to be made to ensure that the asset is not neglected, vandalised, stolen or lost.

While land ownership and land use are the right of indigenous people or of land owners in a property-based economy, the quality and care of that land is also important. In the Elands River Valley, it seems that a once fertile farming valley is beginning to show signs of land degradation and a lack of investment in land care. This may have already begun when the land was farmed by white farmers. Land degradation is a very pervasive and costly global problem, with land everywhere being ruined by population pressures, poor farming practices, by deforestation, by infestation by alien vegetation, pollution and urban development. Even clearing the land for afforestation, and then logging those forests, can result in massive land degradation. It is very expensive, but not impossible, to restore the natural functioning of soil. Also, when land is degraded and people move away, knowledge of cropping the land and living a rural life is lost. This knowledge also forms part of our heritage.

About the author: Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Her current interests encompass cities and urban greening, material culture, degraded peripheries and researching the disintegration (and rehabilitation) of landscapes and buildings. She is currently a Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, QwaQwa, University of Free State (South Africa).

Sources

- Davies L (2021). The 1913 Land Act. The Heritage Portal.

- HIA (2014) Heritage Impact Assessment. Specialist Report Phase 1 Archaeological / Heritage Impact Assessment for the Development of a Footbridge across the Elands River, Elandshoek, Mpumalanga. Adansonia Heritage Consultants, April 2014.

- Item P3602 - Elandshoek. Railway station. (Donated Mr DK Morkel)

- Kunene S. (2012. Mpumalanga Traditional Leaders condemn land invasions in the province. South African government website.

- Lubisi E. (2012). Mpumalanga government concerned about increasing land invasions. SABC News.

- Richardson, D. 2001. Historic Sites of South Africa. Cape Town. Struik Publishers. pg 252

- SA History Online (no date). The Natives Land Act of 1913.

- Wessels E. (2020). Alleged railway track thieves in eMalahleni Court. The Lowvelder.

- Wessels E.(2019). Update: Elandshoek protesters blockade the N4 again. The Lowvelder. November 2019.

- Photo collections online

- Mpumalanga.com Five Arch Bridge.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.