Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

I would like to pay tribute to Clive Scott who passed away in July 2021 at the age of 84. He was a much loved and talented actor who performed on the stage and television during a long career. My tribute takes the form of writing about Dykeneuk, exploring the architect and the context of the grand home. Scott was Clive's professional name; his real name was Clive Cleghorn and he was married to Margie Cleghorn for over 50 years. Dykeneuk has been the Cleghorn home since 1982. It is one of those special heritage gems of Johannesburg. It is a house with a fascinating history.

Family album photos of Clive and Margie Cleghorn (Luke Cleghorn)

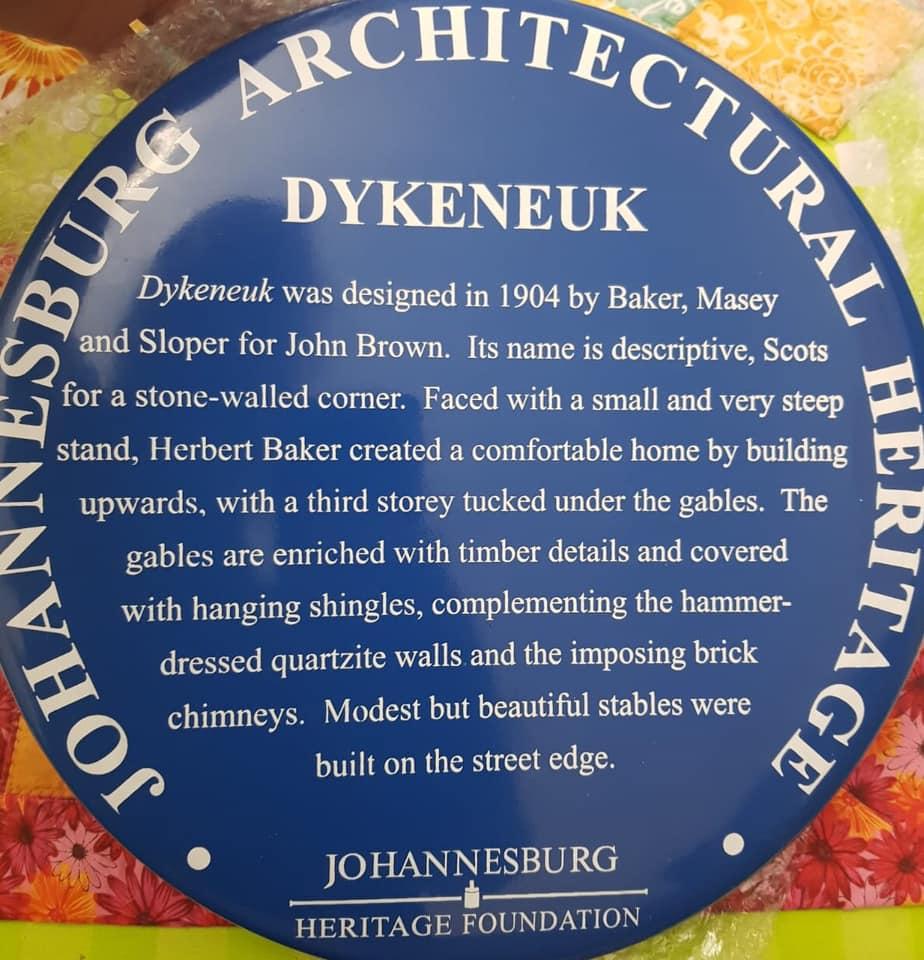

It is the only known “Herbert Baker house” in Kensington and in March 2021 the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation awarded it a prestigious Blue Plaque. It is located at 14 Katoomba Street, corner of Alice Road in Kensington. It is a Baker house in miniature but if walls could talk there is another story.

Blue Plaque (Johannesburg Heritage Foundation)

The name is descriptive, Dykeneuk is Scots for a stone-walled corner. This heritage house is a good example of the Arts and Crafts Style, fashionable and popular in the late 19th and early 20th century both in England and in South Africa. It is a style which emphasized the use of local materials and hence stressed “the vernacular”. In South Africa it meant an adaptation to the local landscape and the stones and rocks of the Witwatersrand ridges. The carefully dressed and crafted quartzite walls quarried from the rocky Witwatersrand ridges blend beautifully with the Baker style. Stone roof tiles and tall red brick chimneys are a distinctive feature of many of his Johannesburg homes. The house is a charming three storey stone home that sits well on the slope of the hill as Katoomba street rises towards Highland Road. It is a compact home with rooms that are balanced and well proportioned. The most striking features of the house are the high quality craftsmanship and the use of local materials - hammer dressed mountain stone, shingle tiles, wood, Etruscan concrete columns, the mix of oriel, bay and dormer windows, the brick chimneys. The house has been beautifully conserved with very few changes; there were additions to outbuildings at later dates.

The outbuildings were designed with horses and carriage in mind (Kathy Munro)

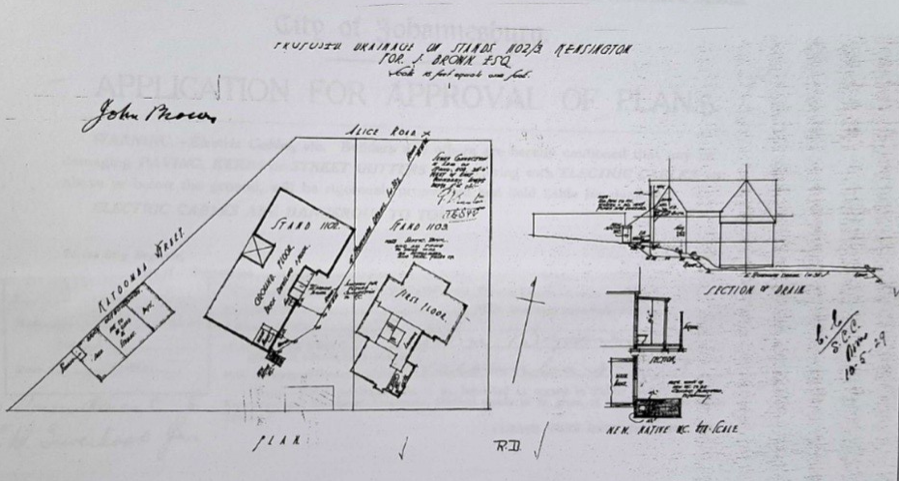

Although Mr Brown owned two stands, the site is an awkward one; the shape of the stands is defined by the typical Kensington slope and so the house rises upwards. It was commissioned by John Brown Esquire in 1904 when he approached the practice of Herbert Baker, Masey and Sloper to design a home for him and his family. The cost of the house when it was built was £1465. The interesting drainage plan for stands No 1102 and 1103 pictured below has been supplied by Kensington Heritage’s Isabella Pingle. The plan carries the signature of John Brown and shows the orientation and positioning of the house on stand 1102 with the frontage on Katoomba Street but that the drainage runs across the second stand (1103).

The Drainage Plan

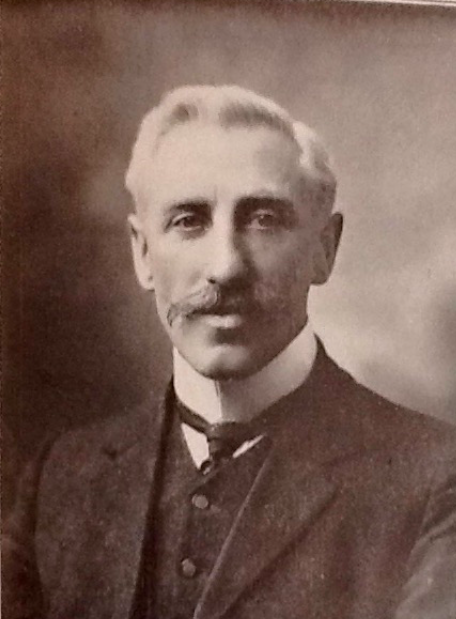

In 1904 Kensington Estate was a new suburb and land was a hot commodity. Unfortunately we know next to nothing about John Brown. He must have been one of the earliest purchasers of two stands in Kensington. There is a photograph of John Brown Esq in the 1906 Men of the Times, the large promotion volume published by the Transvaal Publishing Company; oddly this photograph is not attached to a biographical sketch. Could this be the John Brown who commissioned Dykeneuk?

John Brown?

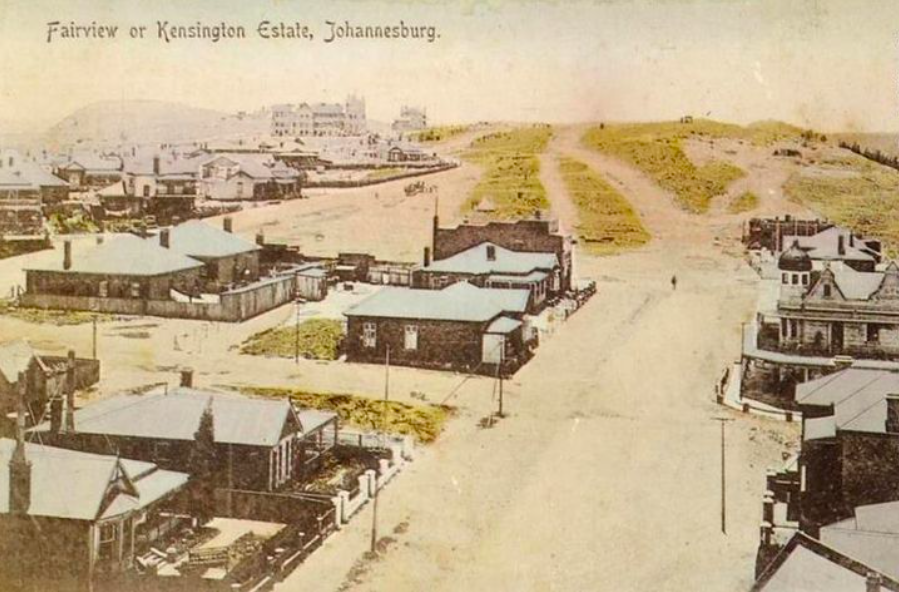

The Kensington Estates Company began an energetic marketing drive to sell stands in the newly laid out suburb. A sketch plan of the location of Kensington together with an advertorial was written up and appeared in the Transvaal Critic as well as the Rand Daily Mail in a series of postings in 1904 and 1905.

Advert for Kensington Estate

Old map of Kensington Estate

Old postcard of Kensington Estate

We are fortunate to have the approval document dated 31 October 1904; it is useful because the standard form provides details of materials (external walls to be built of mountain stone and hard burnt brick, internal walls of hard burnt brick, mortar to comprise three parts sand and one part time, foundations to be of mountain stone etc.). The architect is clearly identified as the firm of H Baker, Masey and Sloper and the signature of the owner was provided. It is this level of detail that supports the heritage case.

The Arts and Crafts style became popular in the late 19th century and the early 20th century in England and was the inspiration of this design. With a blend of comfort and a touch of the vernacular in the use of local materials, it was well suited to Johannesburg and the development of a British blended architecture on the Highveld after the Anglo Boer War. Dykeneuk is a fairly modest house compared to the grand Baker inspired homes such as Northwards, Bedford Court, Marienhof (now Brenthurst) or even Stonehouse, commissioned by Lionel Curtis on Rockridge Road, Parktown. Curtis was the right hand man of Milner tasked with reshaping town government. Stonehouse soon became the home of Herbert Baker when he was first a bachelor and in 1904 he brought his new wife to that house.

Old photo of Northwards

Old painting of Bedford Court

Stonehouse (The Heritage Portal)

The first notable point about Dykeneuk is that it is not in Parktown. It is located to the East in Kensington which was planned as a very different kind of suburb for professional men of means. Although 4, 2 and 1 acre plots of land could be bought and Kensington had the appeal of accessibility and fine Ridge views, none of the Randlords (men at the top of the cluster of mining groups) built their mansions here. Kensington did get its Baker home but the design architect of the house was Ernest Sloper.

Explaining how Dykeneuk became a landmark home of Kensington has to start with the Baker story and the establishment of his practice in the Transvaal. Sloper has to be fitted into the story; he was an important architect on the Johannesburg scene for a few brief years between 1902 and 1907. Ernest Sloper was born in 1871 in England. He joined the Baker practice in 1902, when Baker recruited him to work for his office. His actual name was Ernest Sloper Willmott. He dropped the name Willmott during his South African years but became Willmott again after his return to England in 1907. These name changes become confusing.

Sloper, to use the name he was known by in South Africa, became a partner in 1903, and remained with Baker and Masey until 1906. He then left the Baker practice and returned to England in 1907 and continued to practice until his death in 1916.

We need to expand on these brief facts. Sloper’s background was that of architect and civil engineer. He was a talented young man and by the age of 31 had experience as an architect of churches in the practice of G F Bodley in London and had also designed some small houses in England. It was this experience he brought to the Johannesburg practice; his experience was valuable to Baker because he had a very good feel for English domestic and church architecture.

Herbert Baker came to the Cape because of his friendship with Cecil Rhodes. He arrived in Cape Town in 1892 at the age of 30 and his early work was in the Cape. Baker came to Johannesburg in 1902 persuaded by Lord Milner at the end of the war to leave his Cape Town practice in the capable hands of his partner Francis Masey. It was a new beginning for Baker; he had established a good reputation and the move to the Transvaal gave him a national stage to achieve even greater success and enduring fame in the two new British colonies of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State as well as in Natal. His was a large practice and there were offices in Cape Town, then Johannesburg and later too in Bloemfontein. It has been said of him, that he was “the rainmaker”. He had all the political and business connections to attract all the elite in business as his clients. To live in a Baker house and to worship at a Baker church was to have arrived at the pinnacle of social success.

Baker, born in 1862, was touching forty when he established his Transvaal practice. He was mature and experienced. In the coming decade he built his reputation as a star architect, reliable, innovative, clever, and unique. The style was a blend of Cape Dutch, classical symmetry, echoes back to Palladio, high quality craftsmanship and using local materials. He left a superb legacy to South African architecture. It was an extraordinary flowering before Baker left for India and later settled again in England. His oeuvre included grand mansions for Randlords, churches, public buildings, schools, university buildings and office blocks. His range was wide and the distinctive Baker designs of the Edwardian decade culminated in the great commission of the Union buildings on Meintjes Kop in Pretoria, the new administrative capital of the Union of South Africa. No commission was too big or too small for the growing practice. He was a giant of a man, who towered above his partners. There were four partners during his South African years - Francis Masey, Franklin Kendall, Ernest Willmott Sloper and finally Francis Leonard Hodgson Fleming.

Watercolour of the Union Buildings by Herbert Baker

Despite the success of the growing Baker practice over the years, Baker did not reject commissions for even modest sized homes. Every job mattered and Dykeneuk fits into this category. Enter Ernest Willmott Sloper. Baker met him in England on a 1902 visit and persuaded him to emigrate to South Africa. Sloper’s rise was rapid and by 1903 he had become a partner and the name of the firm changed to Herbert Baker, Masey and Sloper. These were enormously productive years for Baker and his colleagues as a deluge of commissions followed - the great houses in Johannesburg, the Eckstein compound small homes in Parktown, homes and churches in Pretoria. Then came the Bloemfontein public commissions as well as the Kimberley Boer War Memorial to the Honoured Dead, plus the buildings for the Duke of Westminster’s estate in the Orange Free State. There was even work in Natal. Sloper took on more of the administration and design work. Baker went on a long vacation to England in 1904 (a sojourn when he married his cousin Florence Edmeades).

Baker described Sloper as not only a reliable assistant, but “an excellent fellow with great character and distinction in his work." In his memoirs, Architecture and Personalities, Baker refers to Sloper as his first partner in the Transvaal (he refers to him by the name of Willmott); Baker complimented Sloper: ‘he has shown great gifts in educating builders and craftsmen to better methods of building and the use of local materials. The excellence of the walling built of the hard koppie stone was largely due to his perseverance and encouragement to the masons”. (page 56)

Sloper took charge of starting the new buildings for Roedean School with John Barrow as contractor. He sent a sketch for an Anglican Church in Krugersdorp. In fact the years from 1902 to 1904 were wonderful years for Baker and the partnership. Baker was a member of the new Anglophile social elite of Johannesburg and Pretoria. Edwardian society dinner parties could provide opportunities to sketch quick ideas on a table napkin and the commission then clinched with working plans delivered to a client within a day. Speed of conception, clinching a deal mattered. The name Herbert Baker is the remembered name. The issue of whether a specific building is attributed to a practice or whether one singles out the man behind the plans, the design architect comes up not infrequently in architectural history; it is accepted convention to attribute a project to a practice and then to elaborate on the role of the design architect.

Following his arrival in Johannesburg, Sloper put down roots rapidly. In 1903 he designed his own house, Endstead in Escombe Avenue, Parktown built from koppie stone with shingle roof, dormer windows and superbly proportioned, symmetrical wings, spacious and comfortable. It is a home in English Arts and Crafts Style. Sloper is also credited with the design of Bishopskop for the Anglican bishop, Michael Furse and Timewell for Howard Pim on Gordon Hill Road. Sloper signed the drawings for Timewell. These were all well-known Sloper houses and date from 1904. Dykeneuk belongs in this body of work and was commissioned in 1904. It is not as important as the Parktown houses and Sloper's specific role has been downplayed. Sloper houses did not usually give the Cape Dutch gable as the signature feature; but he took to using the local quartzite stone found in abundance on the ridges. Cutting and chamfering the hard stone was not a cheap operation and skilled stone masons were needed.

Endstead

Bishopskop (Journal of the Association of Transvaal Architects)

Timewell (Journal of the Association of Transvaal Architects)

Sloper was also involved in the design of a handful of new churches: St George’s in Parktown and the Anglican churches in Krugersdorp and Randfontein. He took on the Roedean School project, a no frills very functional building. Francis Leonard Fleming joined the office as a junior assistant in 1904 and in 1910 became Baker’s partner taking over the Johannesburg office and the firm progressed as Baker and Fleming.

St George's, Parktown (The Heritage Portal)

For a few short years, Ernest Sloper was a rising star on the Johannesburg architectural scene. He was interested in the possibilities of training architects locally and can be regarded as the founder of architectural education in Johannesburg. He started classes in architectural design at the Johannesburg School of Mines and Technology in Johannesburg with six pupils and Geoffrey Eastcott Pearse (1885-1968) was taught by him. Sloper also served on the Council of the Association of Transvaal Architects from 1905 to 1906. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects so could attach the qualification FRIBA to his name.

J M Solomon in Sloper’s obituary (1916) praised Sloper’s work as follows: “No description will convey the charm of Mr. Wilmott’s work to those who do not know his houses, and nothing I could say would help those who do. The intimate and loving detail; the care in choice of material and site; the evident joy in the choice of single stones and their handling in porch, gable and chimney, is a lesson which young architects will do well to study.”

There is a definite affinity between the Kensington House with the three Parktown homes, although the Parktown houses were larger and clearly cost a great deal more. As mentioned, Dykeneuk fits into the Arts and Crafts tradition and here there is a link to Sloper’s English home and to his book which was published in 1911, English House Design. I shall return to this aspect later.

As Denis Radford makes clear, the name Herbert Baker carries a huge appeal. One says the name “Baker“ and everyone has an immediate mental picture of what a Baker house on the Highveld means. The Baker label has marketing appeal on property websites today. Baker was a prestige architect and his prestige rubbed off on his clients. As Radford comments, there is a certain aura to Herbert Baker’s work and that name alone means that the contribution and creativity of his partners has been downplayed. Masey and Sloper stand in the shadow of Baker. The question arises were the Sloper houses including Dykeneuk simply expressions of Baker’s brilliant designs or did the partners have agency? No doubt there is a level of rivalry and competitiveness in an architectural office. How significant were the Masey and Sloper and later Frank Fleming contributions?

Dykeneuk is a special gem. Doreen Greig commented on Sloper’s use of locally quarried but durable quartzite at Dykeneuk (as well in the Parktown homes): “he used it alone or combined it with other materials; sometimes with rough cast plaster as at Timewell and Northwards, sometimes with hanging shingles as on the gables at Dykeneuk”. (Greig p 118).

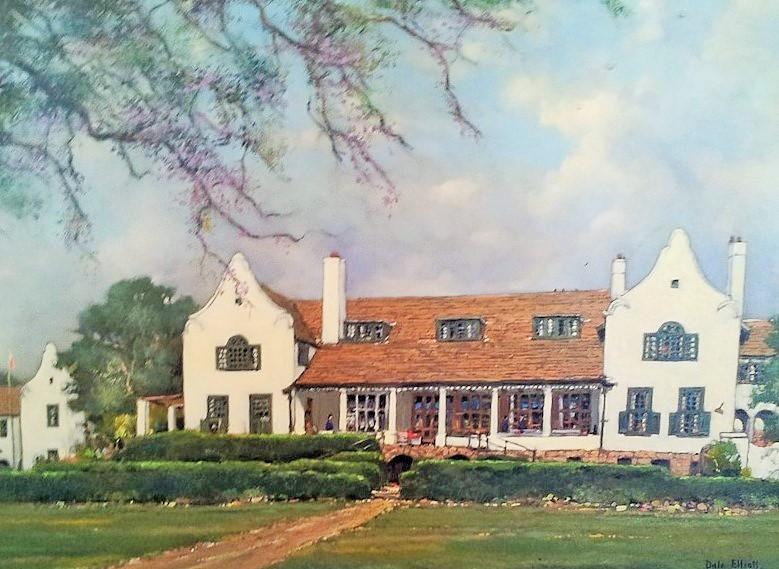

In 1948 the house featured in the Homes of the Golden City, a book about Johannesburg, which had first appeared in 1933 under the title The Golden City edited and published by Alistair Macmillan. After the Second World War, Eric Rosenthal brought out a new edition with the inclusion of photographs of well over 150 prominent Johannesburg homes. At that time the house was identified as the home of Mr J N Bradley and had the label “Sir Herbert Baker” house. At that date the shingle roof was still in place.

Dykeneuk (Homes of the Golden City)

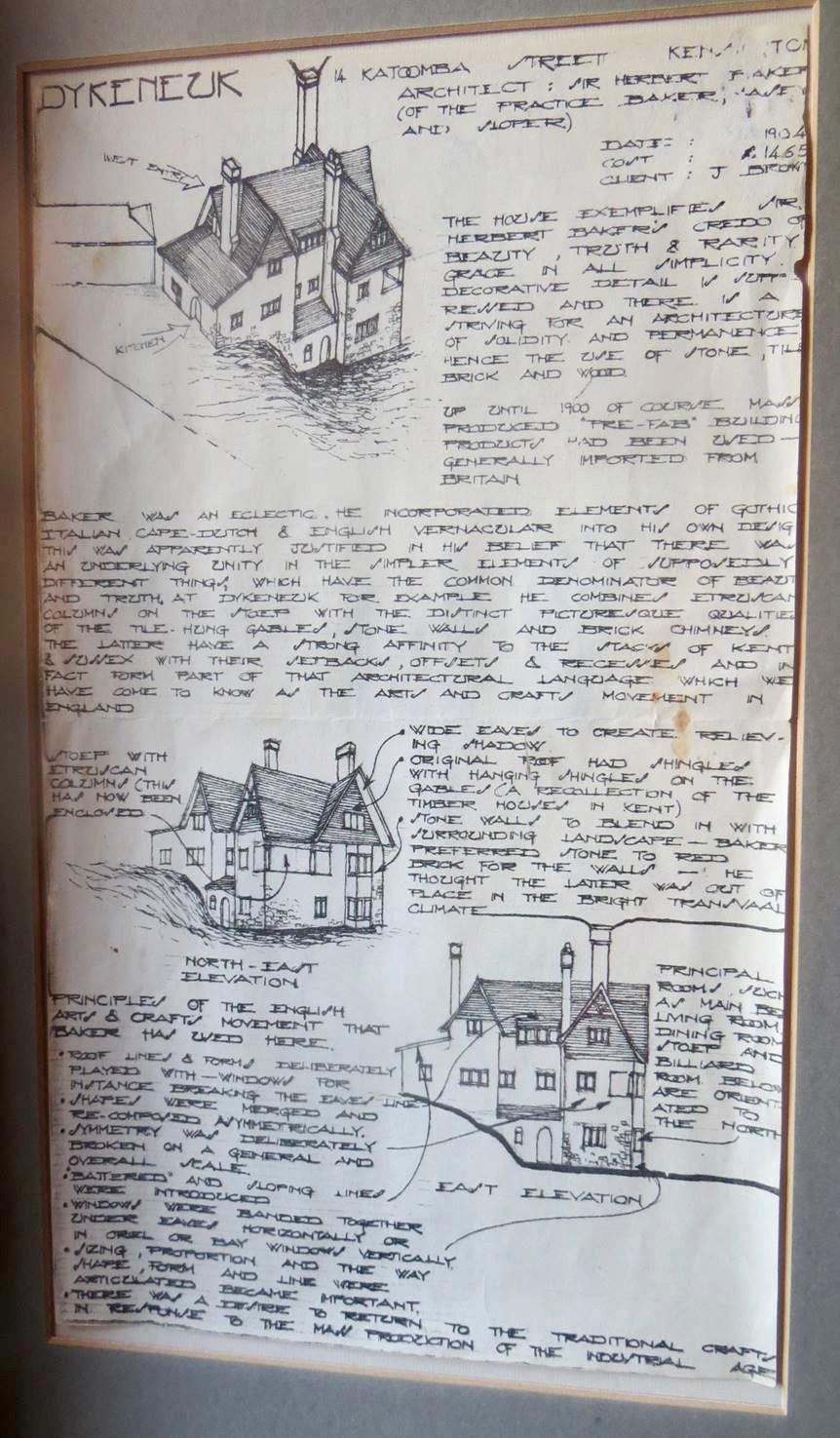

There is a delightful framed combination of description and sketches of different angles of Dykeneuk hanging in the house. It is undated, done by an unknown artist/author, but gives an excellent coverage of the house. My only disagreement with this text is that one should substitute the name Sloper for Baker! A portion of it reads:

The House exemplifies Mr Herbert Baker’s credo of beauty, truth and rarity, grade in all simplicity. Decorative detail is revered and there is a striving for an architecture of solidity and permanence, hence the use of stone, tiles, brick and wood. Up until 1900 of course mass produced “pre-fab” building products had been used – generally imported from Britain.

Baker was an eclectic. He incorporated elements of Gothic, Italian, Cape-Dutch and English vernacular into his own design. This was apparently justified in his belief that there was an underlying unity in the simpler elements of supposedly different things which have the common denominator of beauty and truth. At Dykeneuk, for example, he combined Etruscan columns on the stoep with the distinct picturesque qualities of the tile hung gables, stone walls and brick chimney. The latter have a strong affinity to the stacks of Kent and [unclear] with their setbacks, offsets and recesses and in fact form part of that architectural language which we have come to know as the Arts and Crafts Movement in England.

The Dykeneuk Story (photographed by Kathy Munro)

The Sloper engagement with and work for the Baker, Masey and Sloper partnership started off very well, but those gloriously productive years had a brief flowering. The years 1905 to 1906 were ones of depression but there was still work. The Rhodes Memorial on the slopes of Table Mountain as well as alterations to the Bloemfontein Cathedral, but Baker, Masey and Sloper were not the only architects and work had to be competed for and prices negotiated. It was a cut throat business touting for work and making concessions and reductions off the standard 5% of the contract price for the architect. In 1905 Baker had to deal with a law suit against Dale Lace for final payment on Northwards work. Baker won the case and was paid but in Cape Town there was not much new work apart from the Rhodes Memorial, the St George’s Church at Groot Drakenstein and a church in Turffontein. In these years there was other church work – in Pretoria the Church in Arcadia and in Randfontein the St John the Divine. The newly founded St Johns College commissioned Baker to design the earliest buildings of the school on the Upper Houghton ridge, the building was completed in 1907. In 1906 Sloper ceased to be a partner and the reason given for his withdrawal and subsequent return to England was a lack of work and his own ill health.

A recent photo of St John's College (The Heritage Portal)

In the context of the main jobs Baker and his colleagues were engaged in (despite a so called depression), this explanation seems hardly plausible. How odd it seems that Sloper had built his own house not 3 years previously, only to leave it all behind. Why give it all up and abandon a solidly growing reputation? On his return to England in 1907 Sloper reverted to the name of Ernest Willmott and practised under his own name until his premature death in 1916.

In 1911 Ernest Willmott published a book: “English House Design”. It was a selection and brief analysis of some of the best achievements in English domestic architecture from the 16th to the 20th century. A marketing blurb promotes the book: “This delightful work, which came from the House of Batsford, will indicate far better than I possibly could Wilmott’s taste, culture and scholarly choice of architectural heroes. Few men worked more for the joy and love of creation in a not always sympathetic community than this reticent exponent of all that was best in simple, gentlemanly, domestic architecture.”

I own a copy of this book and despite the poor review in The Architectural Review in 1911, this book has a lot of charm, numerous illustrations and gives a very good insight into Willmott’s approach and philosophy to domestic architecture. This book shows how his work fitted into the Arts and Crafts movement and his thoughts on the philosophy behind this architecture. His starting point was site and its influence on house design; he considered symmetry in design foundational. The garden, the setting and the context for a house has shaped English domestic architecture since the 16th century. There is a chapter on the chief principles of house design which he names repose, proportion, scale, rhythm, colour texture and local influences. He takes the reader through the history of the old English house from the Tudor period to the Queen Anne period. But in his own time he considered the leaders in a revival in domestic architecture – Philip Webb his old firm Bodley and Garner and Norman Shaw. All of the examples of the work of contemporary architects and their canvas were English, but there was one exception and that was Herbert Baker's design for Sir George Farrar at Bedford Court. Willmott did not include any of his own South African houses and I find this quite odd, but he includes his own work at Berkhampstead and Stanmore House. The success of the Garden Suburb movement in Hampstead and Gidea Park owe something to Willmott. But what is not discussed is the South African influences and the types of houses he designed in Johannesburg and Pretoria during those brief years and what he took away from the South African years with Herbert Baker. A house designed by Willmott at Stanmore echoes certain features of the Dykeneuk design. The front façade of his design of Shorne Hill near Totten, Hampshire has a rather Cape Dutch looking gable that would have made Baker swell with pride. This house became a military hospital in the First World War. Willmott designed some fine houses for Hampstead Garden suburb (79 and 81 Hampstead Way). Recent research into Willmott’s architecture in England after his return from South Africa is now being documented.

Postcard of the house at Shorne Hill

I have tried to learn more about John Brown but with little success. The name John Brown is far too common. I have trawled through the online database of the Rand Daily Mail held by the University of the Witwatersrand. There are racehorses that ran at Turfontein; there was the John Brown shipyards on the Clyde, there was John Brown the ghillie of whom Queen Victoria was inordinately fond. I found an unknown John Brown up before a Magistrate and fined for reckless driving while intoxicated in Johannesburg. There was a John Brown Land Boilers (Africa) (Pty ) Ltd. I found a John Brown who competed in Veteran Bowls in Kensington in 1939. The closest I got to the John Brown of Dykeneuk was to find a small post in the RDM for 1st November 1924 that Mrs John Brown of Dykeneuk, Kensington had passed away suddenly in Durban the previous Thursday and that a memorial service was planned at St John’s Church in Belgravia. So it would seem that John Brown was left a widower.

If we turn to building plan and Valuation Roll information, John Brown planned a conversion in the basement of his home in 1937. Hence his ownership of Dykneuk extended from when it was built in 1904 until at least the late 1930s or even the 1940s. In the 1955 Valuation roll the owner was listed as a J L Saltz and in 1969 the plan for the conversion of outbuildings documents the owner as Walter Henry Gresty. The Cleghorns have owned Dykeneuk from the early 1980s until the present. Hence over 117 years there have been only four owners of Dykeneuk. That is a remarkable record.

Main image: View of Dykeneuk's swimming pool and garden (property advertisement circa 2014)

Acknowledgements: I thank Margie Cleghorn and Luke Cleghorn for their hospitality, Isabella Pingle for her keen pursuit of Kensington history and encouragement in writing this article, Diana Steele and Sarah Welham of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation Resource Centre, Parktown Sally McRoberts of the Brenthurst Library, and Marcus Holmes for his stimulating conversations about the relationship of Baker and Sloper/Willmott.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

References:

- Doreen Greig: Herbert Baker in South Africa, 1970, Purnell

- Herbert Baker, Architecture and Personalities, 1944, London, Country Life

- Ernest Willmott, English House Design 1911, Batsford

- Michael Keath. Herbert Baker, Architecture and Idealism 1892-1913 The South African Years. 1992, Ashanti Publishing

- Anna Smith. Johannesburg Street Names, A Dictionary of Street, Suburb and Other Place-names, compiled to the end of 1968. 1971 Juta and Co

- Radford, Dennis, Ernest Willmott Sloper. Pamphlet A2 in series The Architects of Parktown - published by the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust , in The Parktown Collection, 1987

- Artefacts website - Ernest Willmott Sloper

- Journal of the Association of Transvaal Architects, no 3, vol 1, September 1916. Obituary for Ernest Willmott

- South African Architectural Record July 1946, p161-184, Obituary for Herbert Baker.

- UK Modern House Index, online database of British houses of Architectural interest from the 1920s to the present - see entry for Ernest Willmott

- Rand Daily Mail archive, University of the Witwatersrand Library.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.