Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The saddle, buffed smooth from many years of use, shimmers in the lampshade’s warm glow in the War Room at Smuts Museum, Irene, Pretoria. At the rear end of the saddle, its brass lined cantle follows the contours of what would have been Charlie’s loin. The seat is light brown. The skirt and saddle flaps are darker. Stirrup leathers and stirrups dangle loose. Who knows, the saddle may once even have belonged to an English officer.

Items exhibited in the War Room of the Smuts Museum, Irene, Pretoria. General Jan Smuts’s saddle, saddle bags, telescope, binoculars and case, fragment of Charlie’s bone, fork, and four books: Holy Bible, Greek and Latin Testaments, Xenophon’s Anabasis. Photograph taken by the author with the assistance of the Smuts Museum (August 2025).

During part of the South African (Anglo-Boer) War, the saddle bore the proud figure of General Jan Christiaan Smuts, Boer commander. Rider, saddle, and horse (described by the General as “one of the best horses on commando”) had grown inseparable; that is, until 7 September 1901 when a sudden burst of gunfire shattered the eerie silence in the gorge and severed the trio’s tight bond. Four men, including Smuts, had ridden into an ambush.

One bullet struck a fatal blow to Martiens Adendorf, one of three skilled scouts who accompanied Smuts on reconnaissance that day. They were searching for a way off the mountain for their commando and they wanted to appraise the enemy’s whereabouts. Martiens’s brother, Willie, whose horse was killed under him, and Joh(annes) Neethling, would succumb to their wounds a few days later.

The bullet that was meant for Jan Smuts struck his faithful horse at the knucklebone. The girth broke. Smuts fell off, saddle and all. He escaped in a cloud of dust in the ensuing confusion and rolled into a donga. As has been suggested by Ben Mclennan from the Anderson Museum in Dordrecht, Charlie was probably not killed in the skirmish, but presumably put down after the incident – someone later handed a fragment of the bone from the equine warrior to the commander’s wife, Isie Smuts.

That night at Moordenaar’s Poort near Dordrecht, in the dim light of the crescent moon, the farmer’s grandmother, Ouma Roodt, sent her servant girl with a blanket and some food to the wounded Neethling, still stuck at the scene of the ambush. He asked her to retrieve the valise that was attached to the saddle. According to the then owner of the farm, DW Schoeman, it contained, amongst others, General Smuts’s Holy Bible, Xenophon’s Anabasis, and a photograph of his wife, Isie. Ouma Roodt, who buried the valuables, returned them to the Boer commander in 1903.

General Jan Christiaan Smuts, his horse, Charlie (“one of the best horses on commando”), date unknown. Photograph on exhibition in the Smuts Museum.

If Smuts had lost his horse and saddle that day, who was it that would be found in Jan Smuts’s saddle for the next eighty years? And how did Smuts’s saddle end up on exhibition in the War Room?

Enter Cpl George Henry Moffett, a member of the Cape Police, renamed the Cape Mounted Police after the war. But who was this corporal?

Cpl George Henry Moffett in uniform. Circa 1900. Photograph from the Moffett family archives.

The military was in George Moffett’s blood; it was also the cause of his tears. He was born to August and Elizabeth Wende. They were two German immigrants who, as children, were carried to the British Kaffrarian shores by the proverbial swell of circumstance and tides of time during Sir George Grey’s 1858/9 immigration scheme. Sadly, thirty-two-year-old August lost his life as a volunteer on patrol during the Ninth Xhosa War. His son and only child, George, was three years old.

A year later, in 1879 George’s widowed mother married William Moffett, a Sandhurst graduate and erstwhile officer in the Thirteenth Prince Albert’s Light Infantry Regiment, quartered in Grahamstown. George and six younger half-brothers were raised in the Moffett home in Xalanga, Emigrant Thembuland, between what would become the towns, Elliot (Slang River) and Cala.

George, who also lost two half-brothers in the line of duty, one during the Siege of Kimberley, and another in the dusk of the First World War, joined the Cape Police in 1895. Soon after his appointment, George was seconded to the Bechuanaland Field Force that was sent to British Bechuanaland (now Northern Cape) to arrest Chief Galeshewe and to deal with the Batlhaping and Batlharos revolt in the Langeberg mountains between Kuruman and German West Africa.

When war broke out between Britain and the Boer Republics on 11 October 1899, Cpl George Henry Moffett, a servant of the Crown, was stationed at Jamestown in the north-eastern corner of the Cape Colony, 22 miles from Dordrecht, as the crow flies, and equally close to Moordenaar’s Poort. Automatically he became a resource in the British war effort, and would remain one until the end of the war. This fact brings us closer to solving the mystery of the saddle.

We don’t know whether Cpl Moffett was a participant in the ambush of Smuts and the three scouts, or whether, as a member of the Cape Police, he cleared the scene of the skirmish. What we do know for sure is that Jan Smuts’s saddle ended up in George’s possession.

Directly after the war, and with George now married, Jan Smuts’s saddle followed him to Bethulie Bridge Police Post where George may have been involved in dismantling the Bethulie Concentration Camp. In 1905 he was transferred to the rising and bustling town of Indwe, twenty-four miles south east of Dordrecht, and promoted to the rank of sergeant. Once again, Jan Smuts’s saddle joined the trek.

George left the Cape Mounted Police in 1908 and began to trade. For the next nearly sixty years his shop - GH Moffett General Dealer (later GH Moffett and Son) in Barkly Street - served the local community. Twenty odd years after settling in Indwe, George also purchased the farm, Stilfontein, in the shade of the Waschbank mountains, approximately seven miles from town. When George’s son, Denzil, returned from Grootfontein Agricultural College in the early 1930s, he assumed farming responsibilities. Father and son used the saddle on the farm. It was casually referred to in the Moffett family as Jannie Smuts’s saddle.

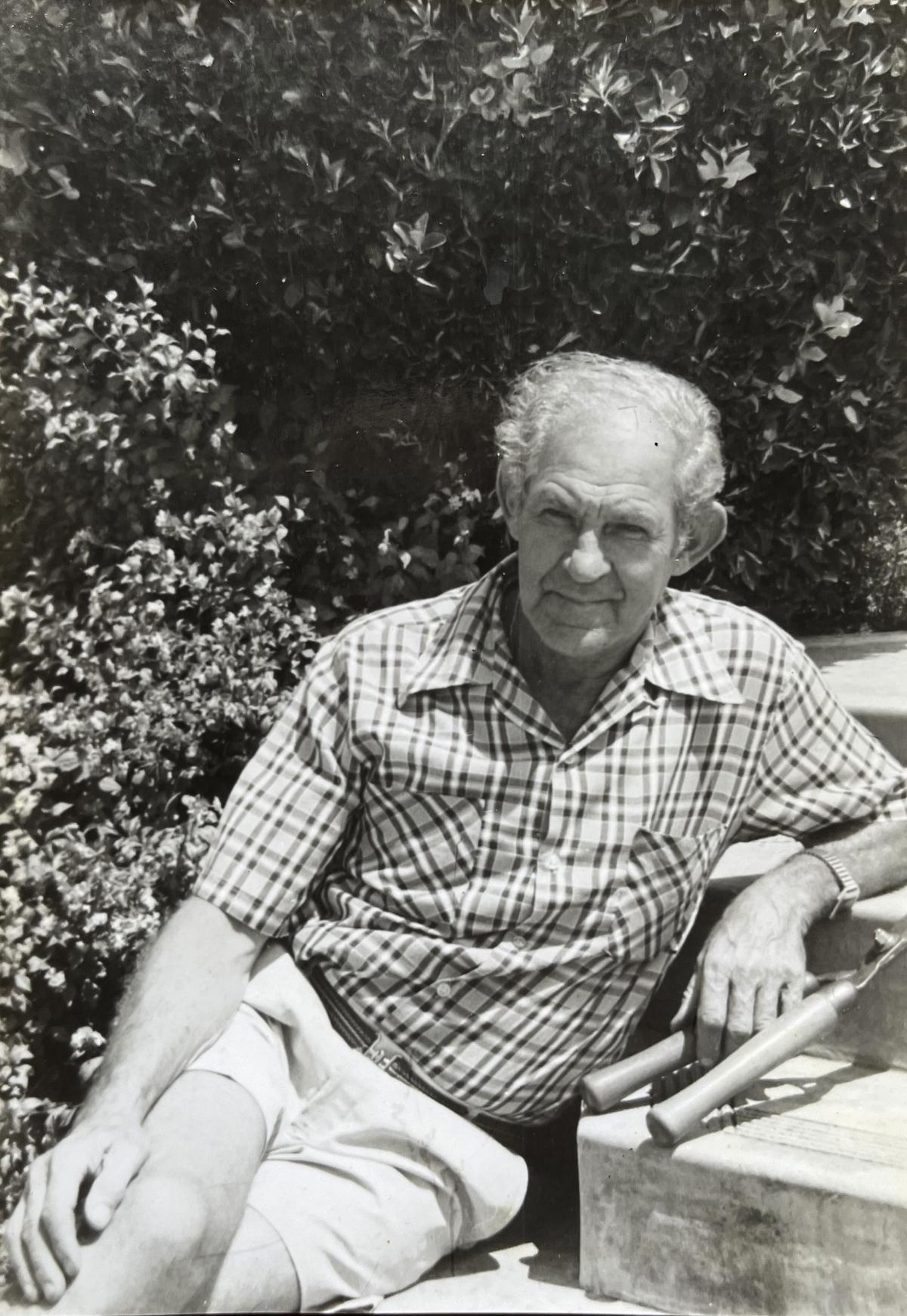

George Moffett’s son, Denzil Winston Newton Moffett in the 1980s, when the saddle and other articles were handed to the museum. Photograph from the Moffett family archives.

The eighty-year-old General died in May 1950 on the family farm, Doornkloof, Irene, in the house where the saddle is now exhibited. Indwean George Moffett died in his house in Wodehouse Street, Indwe in May 1963 at the age of eighty-eight. Son Denzil sold Stilfontein and relocated to Mooi River in Natal. Again, Jannie Smuts’s saddle was not left behind.

In 1981 the Moffett family donated various historic articles to the Howick Museum. In her letter of 27 June 1981, the museum’s curatrix, Pearl Scotney, thanked Denzil Moffett on behalf of the Museum Committee for the donations, and for the loan of, amongst others, “the saddle with girth, stirrup leathers and stirrups which belonged to General Smuts.” A few years later, historians agreed that the saddle should become part of the Smuts Museum exhibition in Irene.

Jan Smuts could not have anticipated that, nearly a century after the incident at Moordenaar’s Poort, the trio would be reunited at Doornkloof: the General’s saddle and Charlie’s bone fragment in the War Room, and his own remains scattered on the top of Smuts Koppie – the rugged hill behind the house. Indweans, George Moffett and his son Denzil played a pivotal part in this unlikely reunion.

George Henry Moffett was my grandfather. His youngest of ten children, Alice, was my mother.

Postscript: In the dilogy, The Indweans, I meticulously pieced together facts, anecdotes, and aural evidence to tell the story of my ancestors (in The Tale of Tom and Alice) and of Indwe and its community (in Heart of my Hometown). As for how my grandfather acquired the saddle, I could find no other plausible explanation other than what I have written above.

Main image: George Moffett (standing, centre) and fellow officers stationed at Jamestown during the South African War. Circa 1901. Photograph from the Moffett family archives

Eugéne Barnard – Boysie to family and school friends – grew up in Indwe in the nineteen-sixties. His childhood dream of becoming an architect was realised when he graduated from the University of Port Elizabeth (now Nelson Mandela University) with a Bachelor of Building Arts (1976) and Bachelor of Architecture (1978). For nearly four decades he exercised his passion – architecture – from his base in Polokwane, Limpopo. He and his wife, Stella, whom he met at university, now live in Pretoria. In addition to practising architecture, he is a qualified arbitrator and mediator. Eugéne’s father was a history teacher and keen sportsman, and his mother was a homemaker, librarian, musician, and tap dancer. His own interest in history, his fascination with words, the enchantment of stories, his fond memories of a happy Indwe childhood, and a gradually developing curiosity in genealogy, laid the foundation for the research for and writing of the two volumes of the town and its people: The Indweans - The Tale of Tom and Alice; and The Indweans - Heart of my Hometown.

Bibliography

- Smuts in the Stormberg: Sandy Stretton

- Commando, a Boer Journal of the Anglo-Boer War: Deneys Reitz

- Jan Smuts, Unafraid of Greatness: Richard Steyn

- https://www.smutshouse.co.za/about-sh/

- Relics of the Smuts Ambush: Facebook post (2017/09/10) by the Anderson Museum

- Howick Museum's letter dated 27 June 1981 to Denzil Moffett

- The Indweans – The Tale of Tom and Alice: Boysie

- WCARC (Western Cape Archives and Records Services) KAB. CO. Volume 4202

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.