Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

One of the most remarkable early European visitors to the Magaliesberg region was the Scottish missionary Robert Moffat. He was born on 21 December 1795 in Ormiston, Scotland. His parents were not wealthy, and at the age of 13, he was apprenticed to a gardener. It was hard, physical labour, which no doubt developed in Moffat a toughness which stood him in good stead later in life. In the evenings Moffat attended classes, during which he not only learnt Latin, but was also given instruction in blacksmithing and playing the violin.

By 1815, Moffat had found employment as a gardener in the village of High Leigh, Cheshire, England. It was here that he came into contact with Methodist evangelists, and readily accepted their message. Moffat went through a life-changing conversion experience, and committed himself to a life of missionary service. In September 1816, he was formally commissioned as a missionary of the London Missionary Society (LMS), and was sent to South Africa.

After three years in Namaqualand, he returned to Cape Town, where he married his fiancée Mary Smith. The young couple travelled first to Griquatown, where their daughter Mary (later to marry David Livingstone) was born. From there they moved to the LMS station at Kuruman in the northern Cape (see main image).

The Kuruman mission was established to minister to the Batlhaping (one of the Tswana communities). Moffat was a very practical man, who not only preached to the people (he had learnt to speak Setswana), but also taught them skills like irrigation, farming, carpentry and blacksmithing. Within a few years, the community at Kuruman was flourishing.

In July 1823, an event occurred which greatly enhanced Moffat's reputation. Dithakong (home of the Bathlaping) near Kuruman was threatened by a large body of Sotho refugees fleeing other groups displaced during the time of great turmoil known as the Difaqane. Moffat was not a combatant, but he played a prominent role in organising the successful defence of Dithakong by Griqua horsemen armed with firearms. Moffat became known not only for the industries that he was developing amongst the Bahlaping, but also as their protector. In due course, reports about this remarkable man reached Mzilikazi, king of the Ndebele, at his royal kraal Kungwini in the Magaliesberg, close to the pass known today as Wonderboompoort.

In 1829, Mzilikazi sent five of his headman to Kuruman with instructions that they were to persuade Moffat to come and visit the Ndebele king. Moffat reluctantly agreed, and set out on the long journey to the north-east. Near the western end of the Magaliesberg and north of the range, Moffat was astonished to see a huge tree in which no less than seventeen rudimentary huts had been constructed. The local Bakwena people had resorted to this way of living in order to protect themselves against the ravages of lions.

The Ndebele headmen took Moffat eastwards along the northern side of the Magaliesberg. As Moffat travelled along the foot of the range, he saw the ruins of numerous stone-walled villages which had been destroyed by the Ndebele. When they reached the pass known then as Mpande (today Kommandonek), they crossed over to the south of the Magaliesberg. A journey of four more days eastwards brought them to Mzilikazi's royal kraal Kungwini. There they were greeted in dramatic fashion by hundreds of Ndebele warriors, and ultimately by Mzilikazi himself. Moffat spent eight days with Mzilikazi. He notes that he received many tokens of friendship, and that he was much struck by the way in which Mzilikazi expressed his gratitude to Moffat for making the long journey from Kuruman. It was the beginning of a friendship which was to endure undiminished for decades.

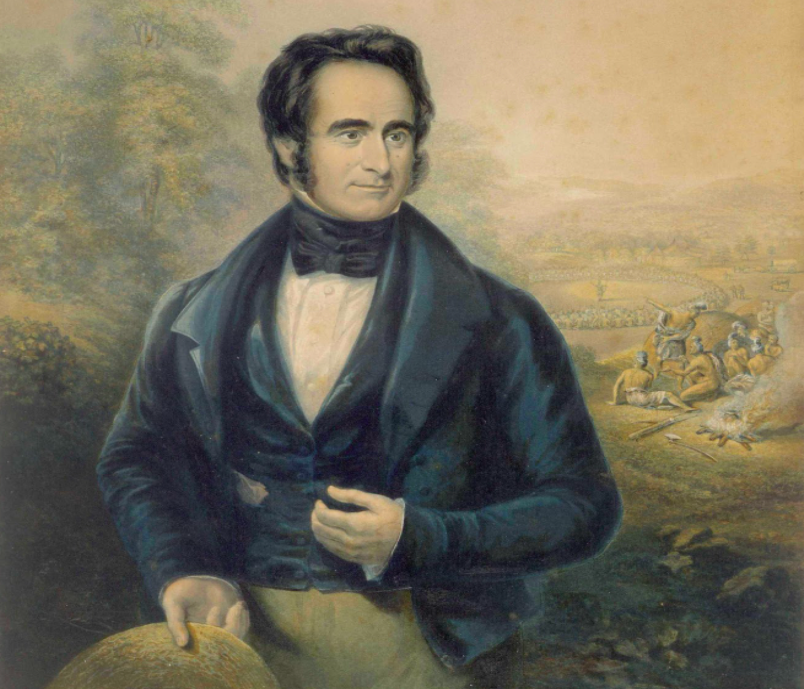

Robert Moffat, as painted by George Baxter in 1843 (From Wallis 1976, opposite half title page)

Moffat was not slow to explain to Mzilikazi that he was a missionary, a "teacher from God", and that it was his desire that missionaries should also be sent to Mzilikazi and his people so that they could hear the Gospel. Moffat also did not hesitate to speak to Mzilikazi about the devastated Tswana villages which he had seen, and to warn him that "the innumerable bones which lay scattered over the plains seemed to call to heaven for vengeance". To all of this, Mzilikazi listened attentively. It did become clear, however, that converting Mzilikazi to the Christian faith would be no easy matter. Moffat, however, was not deterred, and spent many hours explaining various aspects of Christian doctrine to the king.

While with Mzilikazi, Moffat saw first hand that the king ruled the Ndebele with an iron rod. He witnessed several executions, including that of a man who was bound and pushed into a deep pool, there to drown and be devoured by the crocodiles. Moffat writes, "The government of the Matabele is tyrannical in the strictest sense of the word. All the people, as well as what they possess, are considered Moselekatse's. His word is law, and he has only to lift his finger and his order is promptly carried into execution". Mzilikazi expressed his desire to obtain firearms, and particularly a large gun (cannon), which he said he would use to defend himself against attacks by the Zulu. Moffat explained that he was not permitted to supply firearms, and Mzilikazi did not pursue the matter further. Moffat notes that Mzilikazi was "uncommonly pleased" with the gifts which Moffat had bought, including a gridiron, various cooking utensils, and beads.

In his journal, Moffat gives us the earliest description that we have of the man Mzilikazi. It is clear that Moffat found much in Mzilikazi which was appealing to him. He writes, "He is exceedingly affable in his manners" and "cheerfulness predominates in him." At the same time, Moffat was fully aware of the stark contrast between Mzilikazi's friendliness towards him, and the nature of his rule. He concludes, "He might be taken for anything but a tyrant from his appearance, but for all that, it may be truly said of him he dipped his sword in blood, and wrote his name on lands and cities desolate". Moffat was always to be both Mzilikazi's firm friend and his sternest critic. To rebuke Mzilikazi would have meant certain death for any of his subjects, but Moffat, driven by his hope that Mzilikazi would accept the Christian message, never shrank back from doing this.

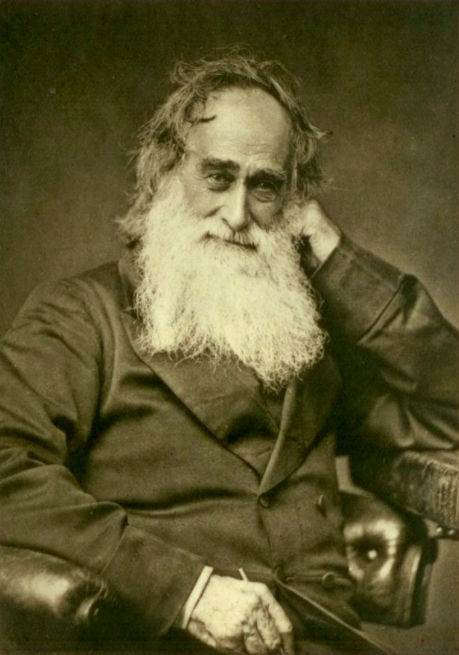

Robert Moffat in his old age (From Moffat 1899, opposite title page)

Moffat was anxious to return to Kuruman, but Mzilikazi was at least as anxious to have him stay for as long as possible. As Moffat puts it, Mzilikazi "contrived, with no little artifice and persuasion, to detain me ten days". When Moffat was finally allowed to leave, Mzilikazi travelled with him in his wagon for the first day, as far as one of the large Ndebele towns south of the Magaliesberg. The Moot is easily recognisable in Moffat's description of the first day's journey: "Our course was directed to where I crossed the Oori [today called the Crocodile River], along a beautiful vale between two low ridges of hills". Before the two men parted, Mzilikazi implored Moffat to visit again. He was to do so four more times, continuing to visit even after Mzilikazi and his people had moved far northwards into what is today Zimbabwe. Moffat's last visit to Mzilikazi took place in 1860, ten years before Moffat retired from his ministry at Kuruman after fifty years' service. We are fortunate that his "Matabele Journals" have been published. They give us a detailed account of his experiences in the Magaliesberg region, and also shed light on his remarkable friendship with Mzilikazi which endured undiminished for more than thirty years.

Click here to download the original article including references.

Andre is involved in development of new exhibits and information panels for Kedar Heritage Lodge near Rustenburg. Kedar, located on Paul Kruger's farm Boekenhoutfontein, is home to one of the world's largest private collections of South African War artefacts, including firearms, swords, uniforms, medals, documents and many other items.

References and further reading

- Carruthers, Vincent, 2014: The Magaliesberg: Biosphere Edition. Pretoria: Protea Book House.

- Moffat, John S., 1889: The Lives of Robert and Mary Moffat. London: T. Fisher Unwin.

- Moffat, Robert, 1842: Missionary Labours and Scenes in Southern Africa. London: John Snow.

- Rasmussen, R. Kent, 1978: Migrant Kingdom: Mzilikazi's Ndebele in South Africa. London: Rex Collins and Cape Town: David Philip.

- Wallis, J. P. R., 1976: The Matabele Journals of Robert Moffat, 1829 - 1860: Volume 1. Salisbury: National Archives of Rhodesia.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.