Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Over the last few weeks the seeds of a very important discussion have been planted with some big names in the heritage sector speaking out. In late September 2015 Dr Franco Frescura, Professor and Honorary Research Associate at the University of Kwazulu-Natal, published a critique of the heritage resources management sector in South Africa. This included statements about the performance of the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) and the various Provincial Heritage Resources Authorities (PHRAs). On 27 November 2015 Katie Smuts, Manager of the National Inventory Unit at SAHRA, and Mr John Gribble, Manager of SAHRA's Maritime Underwater Cultural Heritage Unit, responded to the critique. Both articles are published below. We encourage members of the heritage community to add their views in the comments section at the bottom of the piece (feel free to email admin@theheritageportal.co.za and we will add comments for you).

THE GREAT SOUTH AFRICAN HERITAGE DISASTER - Franco Frescura

It would be true to state that, from a legislative and practical point of view, historical conservation in South Africa is an unmitigated disaster, and has been one since the demise of the old National Monuments Council in 1999. For all its ideological faults and Broederbond associations the NMC had a national infrastructure which its successor, the South African Heritage Resources Agency, SAHRA, had every opportunity of taking over and transforming to meet the needs of the new South African democracy. Instead SAHRA abandoned its regional structures, and retreated to its offices in the Western Cape which are now populated by insecure incompetents more concerned with drawing a salary than in doing the work they are being paid to do. Most of its staff is engaged with issues other than the built environment, and its Council, where most of the problems probably lie, is more focused upon the holding of meetings in airports and stuffing their faces with free nosh than in providing effective leadership at a national level.

Today the only regional bodies that are providing a proper support infrastructure to conservation efforts are the Western Cape and, partly, KwaZulu-Natal, and while the establishment of regional heritage bodies is a factor of provincial government, SAHRA has failed to provide the leadership and driving force to make these a reality. In Limpopo, for example, its heritage staff consists of two persons who know nothing about conservation, collect salaries, and seldom travel beyond their offices in Polokwane.

Heritage Western Cape Provincial Heritage Site Plaque (The Heritage Portal)

Had SAHRA’s management been in any way capable of meeting its functional duties, then it would be taking action, as a matter of urgency, to head off the pending disaster facing our cities through the blind imposition of its 60-year protection rule. In its terms, in 2006 the bulk of South Africa’s post-war housing became “protected”, swamping municipalities with administrative work they had neither the staff nor the knowledge to handle. As most of this housing stock was generally non-descript and of little historical value, a solution should have been simple to implement, but it was never applied.

By 2020 large parts of the CBDs in Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban and Pretoria will be likewise protected, and the fear has been voiced that this will bring property development in these areas to a grinding halt. This will result in a concomitant loss of investment, a reduction in new building development, and a drop in property prices. It will also seriously affect any nascent efforts to restructure the Apartheid City and bring to an end the structural inequality it enforces upon its residents. The national press raised this issue in 2013, but not a single voice could be found at SAHRA to reassure the public that the matter was receiving its most immediate attention.

More recently there has been talk of scrapping the 60-year clause which, under current conditions, will also do away with the need to have existing heritage agencies altogether, but will not remove the need for an active and competent national heritage body capable of administering the Act and of taking proactive action to safeguard the future of our historical built environments.

In terms of the Heritage Act SAHRA was also charged with the creation of a national register of heritage resources but, fourteen years down the line, little such work has been done. Instead the Agency has left matters in the hands of local authorities who, understandably, have been reluctant to allocate precious budget resources to surveys they do not perceive, or understand, to be of any immediate practical value. To the best of my knowledge Durban is the first, and so far only, major municipality in the country to begin this task, and even then its efforts to date have been limited to one small area of the city. A handful of smaller municipalities, predictably all located in the Western Cape, have also conducted comprehensive surveys.

The Playhouse - One of Durban's Landmark Heritage Buildings (The Heritage Portal)

SAHRA has also failed to promote the establishment of regional representative bodies in most of the nine provinces, and in places such as KwaZulu-Natal, it has mandated its work to AMAFA, a provincial agency with few effective powers. In desperation AMAFA recently announced that it would now accredit Conservation Practitioners according to criteria it has invented and has no legal right to enforce. Attempts to organize regional and national workshops to regulate research methodologies towards the creation of a National Heritage Resource Register have been met with dumb silence from Cape Town.

It is no wonder then that today the National Heritage Act of 1999, promulgated in 2000, is a dead letter, and that local authorities, municipalities, private developers and individuals generally ignore its provisions in the full knowledge that retribution is unlikely, and any penalties laughable. The list of buildings and environments lost since 1994 is heart-achingly long, and spans the country from the potential World Heritage Site at Mukumbani, in Venda, down to the very few historical buildings left standing in Uniondale. The Rissik Street post office in Johannesburg was burnt down by its security staff to hide the theft of its brass fittings, and as I write the historical Ndebele village of KwaMsiza, once a potential World Heritage Site, is under threat of demolition from the local municipality who is claiming the land for housing purposes.

The Rissik Street Post Office (The Heritage Portal)

It has been said that every country has the government it deserves, but I am not entirely certain what South Africans have done to deserve the treatment that is currently being meted out to their material culture and historical heritage.

Whether the architectural profession cares to acknowledge it or not, the built environment, all built environment, creates a stage-set within which we play out daily the soap operas of our lives. Architectural historians traditionally hold that a people with a mean architecture will belabour under mean and mediocre values, while buildings with soaring spires and pinnacles will inspire their hearts and minds to greater things. That may or may not be true, but with architecture come the memories of the people and events, real and mythical, from times past, which populate the material artifacts, the built forms, the civic spaces and the environments of our time. Architecture is a continuum, and through it we inherit the thoughts and prejudices and shadows and achievements of previous generations. Thus, at its most basic, historical conservation is concerned primarily with the preservation of the memories which are embodied in our built environments.

It goes without saying that such memories are constructs, fugitive and ephemeral, subject to personal interpretations and selective prejudices. But they are also integral to the built environment, and when we demolish a building, we also extinguish a whole sector of memories from our collective consciousness. Generally we leave it to historians to create the frameworks within which such memories can be stored and interpreted, but even then these are subject to current political dogma and popular opinion which mould the interpretation of facts to suit individual tastes, narrow sectarian agendas and national needs.

This is why we look to architecture to provide a solid and incontestable basis for historical fact. The motives and values of its builders may be subject to periodical contestation and revision, but the bricks and mortar live on. It is probably true to say that most people do not remember their lives as one constant flow, but rather as a sequence of events, much like beads strung out in a necklace. Architecture links our memories into a tangible continuum which gives a sense of perspective to our lives. Take away the buildings and you take away the continuum; take away that continuum and you replace it with a sense of disorientation and personal loss.

At a time when we are faced with collapsing government legislation, obdurate and corrupt officials, and a ruling party that is set upon rewriting history in the worst possible terms, the work of conservation architects becomes particularly relevant.

Restored Government House Pietermaritzburg (The Heritage Portal)

* * * * * * * * * *

SAHRA RESPONSE - Katie Smuts & John Gribble

Dr Frescura makes a number of observations and claims in the article that warrant a response from SAHRA as the organisation that he blames for the state of “historical conservation” in South Africa.

Dr Frescura is a conservation architect and, understandably, that’s where his particular concerns lie, however, he fails to acknowledge that. South Africa’s cultural heritage resources consist of more than bricks and mortar. The narrow view of cultural heritage resources displayed by Dr Frescura to a large degree undermines his argument that SAHRA is presiding over ‘an unmitigated disaster’ because it takes no account of the wide range of heritage resources for which SAHRA is responsible, or the work the organization has, and continues to undertake to ensure their conservation, protection and management, as required by the National Heritage Resources Act (25 of 1999) (NHRA). Dr Frescura also displays a weak understanding of the NHRA, the heritage management system it makes provision for and SAHRA’s role within that system and under the Act. He conflates SAHRA with the principles and tenets of the NHRA, overlooking or unaware of the fact that SAHRA, like the NMC before it, is a statutory body brought into being by the legislation that governs heritage management in the country. Its structure, functions, powers and operations are thus established and prescribed by the NHRA.

This legislation, in an effort to introduce a system of “New Public Management” of heritage, as a progressive, inclusive way of managing heritage resources, makes no provision for regional offices of the national heritage agency – the NMC’s “national infrastructure” he refers to. Instead, and in line with our national Constitution, the NHRA makes provision for three-tiered management of heritage. This means that the responsibility for managing heritage resources is entrusted to and rests with the level of government most appropriate to the individual heritage resources. Thus, SAHRA as the national agency is responsible for managing heritage resources of national significance, and those which, constitutionally, cannot be devolved to other levels of government – underwater cultural heritage, and the maintenance of the national inventory, for example. Sites of significance to individual provinces are, under the NHRA to be managed by Provincial Heritage Resources Authorities (PHRA), which each province may establish for that purpose. Local government is responsible for managing sites of local interest. While this system has its flaws, the NHRA is one of the most forward thinking pieces of legislation in the country, and a world-leading piece of heritage legislation.

Preserving Underwater Cultural Heritage (SAHRA)

Dr Frescura repeatedly overlooks the terms of the legislation to cast SAHRA as the agent in the problems of heritage management in South Africa, implying, for instance, that SAHRA has neglected its duties and left the work to the PHRAs, something which is not upheld by even a cursory reading of the NHRA. What he fails to do in his attack on SAHRA is acknowledge the elephant in the room: the fact that only two provinces – Kwazulu-Natal and the Western Cape – have fully functioning PHRAs, while the rest, for a range of reasons, have not established these regulatory bodies. The same applies to local government, with only a handful of municipalities taking responsibility for the management of heritage at their level and within their jurisdiction. In his comments, Dr Frescura is either unaware of, or chooses to ignore the responsibility of both provincial and local government in managing South Africa’s cultural heritage, and the role of central government in ensuring that the requirements of the Act are met. Instead he opts to cast aspersions on the integrity and impugn the professional abilities and commitment of the team of dedicated professional heritage practitioners at SAHRA who are labouring against the odds to support heritage management in South Africa.

SAHRA has engaged, and continues to engage with all spheres of government to facilitate the establishment and empowerment of the PHRAs: from regular and ongoing discussions with the Department of Arts and Culture (DAC), to Provincial MECs and the chairs of each PHRA – both fully functional and those less so.

In terms of the NHRA (and the Constitution), PHRAs may take competence for managing the provincial built environment, archaeology, palaeontology and matters related to burial grounds and graves. The management of heritage objects, maritime and underwater cultural heritage and the Inventory of the National Estate are the mandate of SAHRA. Where provinces do not have the capacity to manage their own heritage resources, the NHRA makes provision for them to enter into an agency agreement with SAHRA to do so on their behalf. Yet, SAHRA seems to be held responsible for failing PHRAs and successful ones. Amafa, for example, is fully competent and is responsible, in terms of the NHRA and the KZNHA, which predates the NHRA, to handle their own heritage affairs, which they do with great diligence and effectiveness. SAHRA has certainly not “mandated its work to Amafa”, and, as indicated, in provinces that do not have as well established PHRAs as Amafa, SAHRA takes on some of the PHRA’s work.

At present, with only two fully functioning PHRA’s, SAHRA is encumbered with a huge load of work in addition to its own mandated tasks. For example, SAHRA’s Archaeology, Palaeontology and Meteorites Unit (APM) is processing the relevant Section 35 permit applications and Section 38 comments on EIAs and development proposals for the remainder of the country. This is in addition to the requirements of its own, national mandate in respect of managing sites of national significance. In 2014, this additional workload amounted to some 632 Section 38 cases, and some 234 permit applications.

SAHRA works hard, against huge odds, to ensure that our collective national cultural heritage is protected and properly managed. Despite a lack of adequate funding and the resultant limit on its ability to employ the necessary numbers of professional staff, SAHRA accomplishes an astonishing amount: work which is made that much more difficult by uninformed sniping.

In respect of his comments about the 60 years clause as it applies to the built environment, Dr Frescura argues passionately that SAHRA and the heritage management system is badly letting down the protection of the built environment. However, he also complains that the 60 year clause has resulted in ‘South Africa’s post-war housing became “protected”, swamping municipalities with administrative work they had neither the staff nor the knowledge to handle’. Aside from this contradiction, his argument against the 60 years clause in disingenuous. The National Monuments Act, whose passing he laments, protected all historical buildings over 50 years of age. The same buildings whose protection after 2006 as 60 years old structures he sees as problematic were protected after 1996 under the 50 year clause of the National Monuments Act. The problem he points to is thus not something new and local authorities have had previous experience of this issue.

The Act makes it clear that it is the responsibility of local authorities to conduct surveys of their heritage resources and compile inventories that in turn shape their planning and zoning regulations. Were these surveys completed, the 60 year clause could, as Dr Frescura points out, be done away with entirely. Furthermore, as Dr Frescura well knows, simply because something enjoys general protection under Section 34 of the Act, does not mean that development is not permitted. To imply that the 60 years clause stands as an inviolable impediment to development is a misunderstanding of the spirit of the Act.

The scrapping of this clause would not do away with the need for existing heritage authorities. Properly capacitated, these authorities would still be responsible for dealing with matters pertaining to the other kinds of heritage within their sphere of operations, including, but not limited to significant buildings older than 60 years, grading of heritage resources, management of declared resources, as well as all of the management issues related to sections 35, 36 and 38 of the Act.

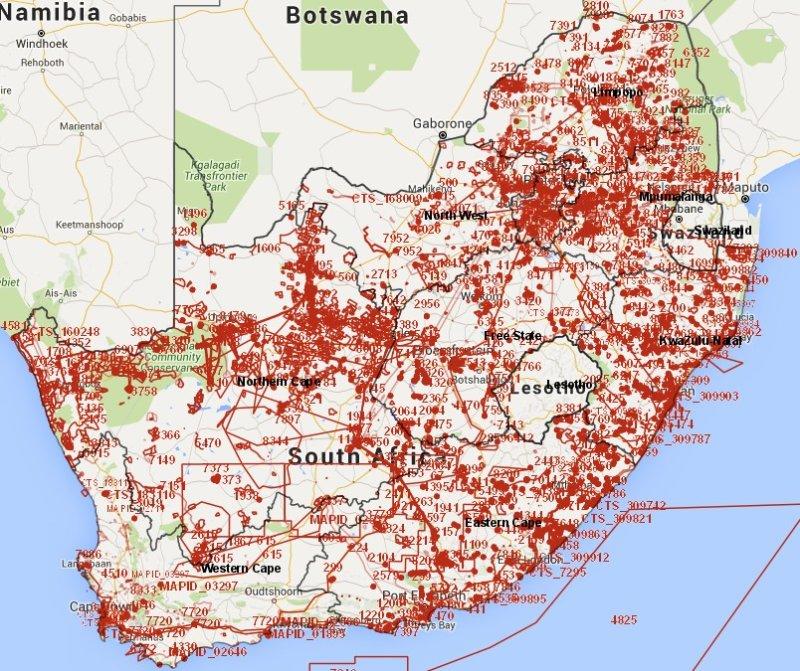

To claim that SAHRA has done little towards creating what Dr Frescura refers to as a ‘national register of heritage resources’ is simply incorrect. SAHRA’s online heritage management platform, the South African Heritage Resources Information System – (SAHRIS), fulfils just that role, while doing far more in addition.

The system serves as a centralised heritage sites repository, a heritage objects database and a sophisticated online heritage management tool that has allowed SAHRA to move to a completely paperless system in the three years it has been in existence. The system also functions as collections management tool, as well as serving as a means to track and monitor heritage crime. All applications to SAHRA, as well as all permits and comments issued are done online, in a way that has improved SAHRA’s turnaround time for responses and its transparency and accountability. The online, open source platform is not only a world class heritage management system, but its integrated functionality as a relational database and content management system is superior in many ways to any comparable system in the world. This system is available freely to all PHRAs and local municipalities, and the general public, and full training and support is provided at no charge by SAHRA. To date there are 7673 heritage cases logged on the system, 23 003 objects recorded, 39 214 sites captured, and 3176 people registered on SAHRIS. Furthermore, SAHRA has undertaken the scanning of their registry files, dating back to 1911, and 17690 files have already been scanned and are already available digitally upon request.

We would recommend the author, and any interested members of the public who have not already done so, navigate to SAHRIS and do some exploring (www.sahra.org.za/sahris).

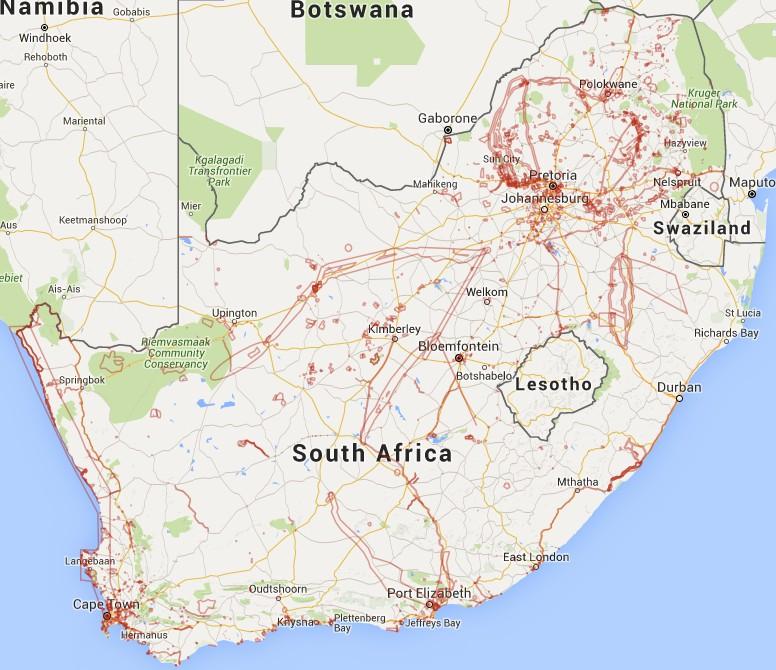

SAHRIS map of heritage cases mapped before 2009

SAHRIS map of heritage cases mapped since 2012

In response to Dr Frescura’s suggestion, in the comments on the article, regarding standardisation of data collection, we at SAHRA agree that this would be a useful step, and using Heritage Western Cape’s recently developed guidelines would be a good springboard for this discussion, although SAHRA would recommend that SAHRIS be used as the repository for the resulting data. Similarly, HWC has recently drafted an excellent guide for local authorities on grading, surveys, heritage registers and heritage areas. As to the issue of the inclusion of Heritage Impact Assessments in EIAs, again, SAHRIS provides an excellent means of assessing the degree of compliance. Where it is apparent that matters are falling through the cracks, SAHRA has actively engaged with the Department of Environmental Affairs and the Department of Mineral Resources to improve compliance, and officers from DMR in several provinces are proficient users of SAHRIS themselves.

Overall, Dr Frescura’s comments are not helpful. They suggest that he neither fully understands the heritage management system established by the NHRA, the role of provincial and local government in the system, or the full extent and broad range of what comprises South Africa’s cultural heritage resources. They also suggest that he has not engaged with SAHRA. If he had – even to the extent of visiting SAHRA’s website – he would have been aware of the range of positive and proactive work this organisation really does and what it accomplishes.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.