Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The article below forms part of Mike Alfred's series on Joburg personalities from the first decade of the 21st century. Click here to view Kathy Munro's fantastic introduction and here to view the series index. The stories were written in 2005/6.

When I talk to 76 year-old Clive Chipkin in his Parkview studio, he tells me that the book was probably in him from the beginning, from as far back as University days, although he doesn’t know whether he intended to write it at that stage of his life. Almost in the same breath he tells me that he’s just returned from a first time visit to Israel where, against expectations, he liked it; particularly the modern, thirties architecture of Tel Aviv and Haifa. Slender, energetic Chipkin, is still designing, still traveling far afield for his work, still recording and relating the stories of Joburg’s always changing, architectural and social structures. His mind is as lively as a sack full of grasshoppers, as dripping with memory as a honeycomb. He’s an idealist, a gossip, intrigued as much by people as by facades and building fashions, perhaps more so. He loves associating buildings and spaces with their creators and linking the creators with their times. I think I might label him a pragmatic intellectual, or an intellectual pragmatist perhaps?

He claims that he came to Wits in 1947, not knowing much about architecture. He thought it had more to do with town planning; more of a social discipline. In high school, when he heard his classmates confidently assert that they wanted to study medicine or engineering, he realised he had to say something, so he said, ‘architecture.’ But, ignorance notwithstanding, he arrived with sophisticated and critical expectations. His father, ‘self educated because he was a breadwinner at thirteen,’ nevertheless subscribed to The South African Architectural Record, edited by Rex Martienssen which the young Chipkin enjoyed reading, or more perhaps, ‘looking at the pictures.’ It strikes me that perhaps Chipkin contrives to play down Dad’s influence on the young designer-to-be.

Wits Great Hall (The Heritage Portal)

When he entered the faculty, he was surprised when his lecturers failed to place the subject in the world at large. Particularly in a world that had just experienced an almost unimaginable war, the holocaust, and, in Chipkin’s view, was now poised to pursue a new Utopia. ‘When I got to Wits, I didn’t know what they were talking about!’ He remembers his first day, his first lecture, given by Gilbert Herbert a well known architectural historian who later migrated to Israel. The mention of Israel leads him to mention a book he read when in that country, called Bauhaus on the Carmel, by the selfsame Herbert describing the Modern Movement German influence on the building of Tel Aviv and Haifa. He reluctantly abandons Israel and goes on to say that Herbert himself wrote another important book: Martienssen and the International Style.

Book Cover

And so back to Gilbert Herbert, on that first academic day, ‘I thought the man was mad!’ Chipkin says, ‘he didn’t tell me a thing about architecture in the world. I’ll tell you what he spoke about, he spoke about a lintel. Now, I don’t understand how you can start a subject like this without any introduction? The department was very peculiar. I always felt everything was a surprise. When the Smuts government fell, the lecturers carried on as though nothing had happened. I was devastated by this post-war shift, and so were a lot of people. We’d been up all night!

I didn’t fit into the course of John Fassler. He was a very good historian and lecturer but I remember him describing the French Revolution, that milestone in human history, as being significant for causing an “unfortunate break in architectural style.” I was never quite satisfied with the Wits architectural school of my period. It was very precious. It had no political attitudes. It didn’t seem to analyse society except as some precious set of architectural forces. And frankly I’ve never been satisfied with that. I don’t see architecture as an esoteric study, divorced from all of us. I learnt more from walking around the city than from attending lectures’.

Chipkin talks about an indirect encounter with Rex Martienssen, significant intellectual and seminal South African Modernist, who had died after an illness, at a disturbingly early age, during World War Two. ‘I never met him, but old copies of magazines lay around. No one respected anything those days. Magazines, anything, just lay around. I picked up a thirties copy of the SA Architectural Record edited by Martienssen. In that issue on the Renaissance, I discovered a need to understand him. I’ve still got that magazine, the cover’s still missing. In a later issue Bernard Cook presented some lovely drawings of war time Cairo: an ex-serviceman had written on the drawings, “out of bounds, forbidden,” which represented his memories of the Cairo brothels. There was no respect for anything! Martienssen was incredible; he helped me to understand Modern Architecture.’ Thus arose Chipkin’s lifelong habit of hoarding reference material, and his growing feeling for the Modern.

Rex Martienssen (Wits University)

Chipkin’s original motivation to write was tied to the desire for understanding and order. He thinks it started at school. ‘I always needed to put my thoughts down together and try and understand, what am I thinking?’ He calls this ‘sitting beside myself.’ He continues, ‘So I have a fairly long history of writing. I wrote architectural papers from about 1958. The first was on New Delhi; I was very entranced by New Delhi which I visited in 1957, traveling Quantas from Istanbul via Bombay, another amazing city where I felt I had arrived home. Herbert Baker and Lutyens were totally out of favour at that stage. They were regarded as the old fuddy duddy classicists, but I was impressed with New Delhi. I must tell you, my father once came home, I guess around 1936, something like that, I was six or seven, and he brought me, and I still have it, a travel brochure, Tourist Board of India. There’s a photograph of New Delhi as a very bare city on the plains, brand new. I used to look at it, whenever I was sick I used to take it out; you know what you do! It became an icon and I’ve never been a classicist. I really do support the Modern Movement.’

‘At varsity,’ Chipkin says, ‘I didn’t really understand the Modern Movement. It became a cliché and I hate clichés. It was only when I went to Paris and walked the streets that I began to understand some of it. I still don’t understand it all. I don’t think anybody can get it right. So I explored and I needed to express, to work out my ideas. I don’t think there’s a mystery to writing; with practice you become able to express what you’re thinking. Of course there’s a vocabulary available – an architectural vocabulary, architecture’s a very well-documented subject.’ Chipkin displays a French architectural vocabulary of about 100 phrases, ‘and I use them as if I know what I’m talking about.’

So it appears that the book, Johannesburg Style, Architecture and Society, was Chipkin’s attempt to provide the missing context, an attempt to integrate Joburg’s buildings and spaces and their designers, with international and local impulses and history. The book describes Joburg’s eclectic architecture from the eighteen-eighties until the nineteen-sixties. Some chapter headings offer clues to the book’s scope: Victorian Townscape; Edwardian Splendour; Johannesburg – Pretoria – New Delhi; Art Deco Johannesburg; ‘Native Housing’; Corbusier in the Suburbs; Little Brazil; Johannesburg – New York. Almost every building Chipkin describes is complete with pedigree. He provides explanations for those who wish to know about its antecedents. He quickly allows one to realize that no building, or at least very few, spring pristine and original from the architect’s uncluttered mind. Johannesburg Style is nothing less than a social history of Johannesburg’s structures and their designers. No one, after reading this book, could ever again be blind to Joburg’s constructed presence. One realizes that one’s living in a very special milieu. After many years of taking one’s surroundings quite for granted, one stops to look around. One begins to put names to various styles of architecture. One begins to ‘collect’ favourite buildings. One is presented with a whole crowd of new daily pleasures. One obtains career insights into the scores of people who so influenced our urbanscape; to mention some of the more famous profiled by Chipkin: Herbert Baker, I W Schlesinger, Rex Martienssen, Gerard Sekoto, Gordon Leith, Andre Hendrikz, Todd Matshikiza and Norman Eaton.

The cover of Chipkin's landmark book

Throughout the book one obtains the feeling that Chipkin is here, right here in Johannesburg, conveying his personal glimpses, his appreciation of the souls and the soul animating the city. In writing about old Broadcast House in Commissioner St, he mentions the sculptural work of Rene Shapshak, whom he describes as ‘an underrated contributor to Johannesburg’s modernity, who made everything else look outdated.’ Shapshak, ‘trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In the late 1930’s the Shapshaks lived at the corner of Bedford Rd, and Regent St, Yeoville, in an old house close to the pavement line. Passers by at the top of the rise on Bedford Rd, could frequently hear the music room echoing to piano pieces by Beethoven or Chopin. That music echoing onto the pavement was part of the Yeoville milieu. There were many music teachers in Yeoville. My mother told me that when as a young woman, she was taking singing lessons an irritated neighbour in Frances St sent round a packet of bird seed with his compliments. One occasionally caught a glimpse of Rene Shapshak wearing his Left Bank beret.’

Old photo of Broadcast House (Seventy Golden Years)

Writing about the Corbusier influenced modern homes in nouveaux riche, thirties-affluent Houghton, he observes, ‘The swimming pool and tennis court were mandatory for Houghton poshness, as were elocution lessons for aspiring daughters, a circular driveway and a double garage for Dodges, Plymouths, Buicks or Cadillacs. A splendid lounge, too, with ball and claw furniture uncovered only on special occasions, and walls hung with investment paintings in amazing gilded frames – Roworths, Irma Sterns and Tinus de Jonghs, even an occasional Gerard Sekoto picked up for a song at the Gainsborough Galleries – as well as Art Deco ceramic plaques and bric a brac picked up at auction sales.’

For me, the book Johannesburg Style, comprises a small treasure chest. I love the way Chipkin deals with the long dead Colosseum Cinema in Commissioner St, where I first saw Marlon Brando in On the Waterfront and Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas in Gunfight at the OK Corral. Chipkin writes: Few patrons of the royal circle ever worried about historical inconsistencies in the Colosseum. Despite its Roman name an Egyptian theme extended from the exterior into the magnificent double-volume Egyptian peristyle hall. Here the giant orders of the lotus columns incorporated Art Deco lighting among the fronds of the capitals and a mezzanine gallery overlooked the crush below. This loggia in turn opened into the medieval townscape of the main auditorium, revealing a cultural diversity of considerable range...

Old photo of the Colosseum Theatre (SA Builder Magazine)

Interior of the Colosseum

There are other elements that cannot be forgotten; the Colosseum orchestra for example in the orchestra pit which rose into view to the vigorous strains of the Espana Waltz by Waldteufel [complete with clicking castanets], conducted by Charles Manning, the Svengali of music whose manic conducting style, long hair swinging crazily, and red complexion and black eyes flushed from extreme exertion rendered him a virtual giant of a conductor. When one bumped into him in the foyer after the show, he was a small man with a sweet smile.

The book was some 20 to 30 years in gestation as Chipkin patiently squirreled away material,‘but,’ as he says, ‘not terribly long in the writing – less than six months with the help of his wife Valerie.’ However, it took eleven years to sell the first impression of four thousand books. Those who anticipate the sequel will welcome the news that Chipkin’s embrace of the period from the sixties up to the present day is complete and soon to be published as Johannesburg Transition, Architecture and Society, 1950 - 2000.

Book Cover

Chipkin in true deprecatory fashion says, ‘There’s no grand message in Johannesburg Style. It grew partly out of my dissatisfaction with what I learnt at Wits; the need to give an alternative picture to their approach at that time. For instance, I think Victorian architecture is very impressive. I see the Arts and Crafts movement as a nineteenth century yearning to build a new society. The book is an attempt to unravel the day to day experience of spaces and buildings that surround us; to understand the city. It’s not just the little, bloated dorp we were brought up in. The most unbelievable subterranean forces are at work here. My book is a reflection of wonder. I’m an explorer. Ideas have always been exciting for me, but I keep away from prescribed views. I’m seen as controversial, I avoid major groupings, I’m a loner, I don’t quite fit in.’

Chipkin’s first job after graduation was with Wayburn and Wayburn in Loveday House. Rusty Bernstein, committed communist and ANC stalwart, ‘very polite, a lovely man,’ who, with Bram Fisher, helped draft the Freedom Charter, occupied the next desk. Chipkin particularly remembers Issy Wayburn. ‘He owed us nothing, he didn’t have to tell us this. He’d come into the office every day punctually at ten minutes to eleven and say, ”Well gentlemen, I think I’ll go and park my car.” Of course there was a pub, the old Gresham there on the corner and he’d come in about an hour and a half later with a glazed look. Rusty would get irritated because Issy would start to reminisce. He’d go to the window and point to a nearby insurance company building, it’s gone now, with big classical columns. He’d say, “You know the story behind those columns don’t you?” Evidently the local manager had to accept the design for the classical facade from his London Head Office, whereas the rest of the building was quite modern. The building was designed by old man Sinclair. Many years later the son Colin Sinclair corroborated the story.

‘Then in his somewhat posh voice, Wayburn used to tell us about old man Stucke, of Stucke, Harrison. For half a century in early Joburg, his was the leading practice: they did all the big banks, that sort of thing. “Stucke,” he’d say, ”wouldn’t bother to draw plans on paper. He’d go onto the workshop floor and with chalk, he’d draw details full scale. He could draw a compass leaf or a bracket with perfect scrolls.” That was the old school and I found those tales fascinating. Wayburn was a raconteur but a slow one. His stories could take an hour. I enjoyed wasting time, but Rusty was always impatient with the endless chatter. Sometimes Wayburn might put his elbow on my board and be silent for quite a long time. It was quite unnerving, but I was intrigued by the stories. I think Wayburn must have fired my writing imagination.

Union House, Marshallstown. One of the buildings designed by the firm Stucke & Harrison (The Heritage Portal)

‘My own father showed that quality too. He took me on long walks. He showed me St John’s College when I was a quite young. I had a complicated relationship with my father, he was quite a Victorian, quite strict, a real English colonial. He believed that nothing was greater than Empire. He really respected it. He was a quiet man. I’ve got an idea that he might have wanted to be an architect. He certainly took me for walks through the quadrangles of St John’s,College which remains one of my favourite buildings. He took me to Pretoria; must have been in the thirties, because when we were visiting the Union Buildings, a gentleman walking across the upper amphitheatre doffed his hat to us. My father told me,”that’s J H Hofmeyr.” I don’t think the Union Buildings are faultless but I have a great deal of empathy for it.

St Johns College (The Heritage Portal)

‘I was fairly sympathetic with Rusty Bernstein’s politics. We got on well and worked as colleagues, senior to junior. I was left-of-centre but I could never take a position like Rusty’s. Having said that, one observed the utter normality and charm of the man; his enthusiasm for cricket commentaries, his hard-work ethos. As a result of our relationship, I designed the structure for the Congress of the People 1955, you know, Kliptown where they presented the Freedom Charter on the football field. What did I design? I designed the toilets, which were gum poles. I have no hesitation claiming it was my greatest work, my claim to history. I have no doubt that some of the great people used my toilets; buckets, hessian, gumpoles. And I designed the stage with Rusty, later made by a skilled carpenter. The seats were logs on supports. The actual charter was collected and assembled in my office by Rusty. Rusty used to get unmarked envelopes in brown paper from Collets bookshop in great Russel St, London: Architektura, Moscow. You knew something was wrong with the Soviet Union when you looked at Architektura. The paper was bad, the photographs were poor, the graphics were pathetic, the architecture was really poor imitation.’

Chipkin remembers the fifties, those first years out of university. ‘The country was alive! We’re talking about the Charter. I heard Mandela’s name. Bram Fisher came into the office. He was Rusty’s great friend; a very magisterial type of man. They were collecting little pieces of paper in a box, which, if you read Rusty’s biography, Memory Against Forgetting, became the Charter of the People, the Freedom Charter. I added a piece of paper. I was a good liberal and I believed in freedom of speech and I put that in the box. Johannesburg Style also grew out of references I collected in a box.

’Only one Chipkin, as far as I know came to Africa, from a village outside Vilna in Eastern Europe. That was in 1868. He opened Chipkin’s Coffee Shop in the Boerewinkel on Market Square in Pretoria, capitol of the old Zuid Afrikaanse Republiek. It was famous for its coffee, Ulyate’s jam doughnuts and Magaliesburg Tobacco. My father’s brother later founded a food, sugar and Ceylon tea business at 132 Jeppe St. Once I met a tea taster from Ceylon in the Trossacks outside Glasgow who knew the name Chipkin, from exporting to that address. In Bombay I bumped into people who, for the same reason, also knew the name Chipkin.

Clive was born at 116B Frances St, Bellevue, in 1929, the year of the Wall St crash. His grandparents, the Unterhalters, owned a rambling verandahed Victorian house at 93 Frances St. It was filled with treasures that would now be regarded as Africana, including a sepia print by Lady Butler called The Remnants of an Army. This showed an exhausted horseman, a Dr Brydon, arriving at Jellahabad, sole survivor of an Afghan massacre. Clive went to King Edward VII Prep and later the High School, often crossing Bedford road to avoid the ruffians of Yeoville Boys Prep. One of his close school friends was the ‘wild’ Sinclair Beiles, later famous as one of the Parisian, Beat Poets associated with William Burroughs.

Main Building at KES (The Heritage Portal)

‘In the thirties, my father was out of work and I was traumatized; only in retrospect of course. One day he came home with a job. I was so excited. But it wasn’t permanent. It was a bad time. We didn’t starve. My mother’s parents were stringent but comfortably off. We moved to lousy places. We played soccer at the Yeoville grounds; swam at the Yeoville baths. I saw great movies at the Yeoville bioscope, the New Yeoville Kinema, a name from the twenties! We couldn’t wait to go to these majestic films: here’s this huge enemy of Afghans surrounding this small British force and you know they’re going to get out of this mess. You hear the bagpipes and here comes the Scottish relief force!

‘On Saturday nights my Grandfather played cards. I used to stay over and take my Grandmother to the cinema. She couldn’t read or write, certainly not in English. She loved every film. She didn’t know what was going on but she loved it, every bugle call, everything. Yeoville shul was important, but I never went to shul, my mother never went to shul and I was very close to my mother. In that shul my parents got married, I had my barmitzvah, my wife and I were married and my sons had their barmitzvahs there. But I can’t romanticize it. My Grandfather preferred cards. He was always making excuses for playing cards. My father liked it as a tradition. He was very anglicised; I’m not sure how Jewish he was. I think he just liked ideas and Judaism is full of extraordinary ideas. He shared ideas with Rev Gordon of St Mark’s Church whose manse was nearby and who could read classic Hebrew and Robbie Burns with equal facility.’

Talking about his own design work, Clive insists that he made his greatest statement with the Kliptown toilet. That’s his posterity. He designed his family home in Craighall Park: partly double storey, hidden from the street, facing north through glass onto a secluded garden. His son called it the Modern Movement on the Highveld, ‘something like that.’ Speaking of the materials Chipkin says, ‘Everyone liked biscuit bricks. I loved Roodepoort bricks, that lovely bluey dark, very much from our area. I like climatic houses, houses that respond to the climate. I’m never quite sure what they’re going to look like.’ He points out the window at the intriguing house which he designed for his daughter. ‘This, this funny thing here, grew over an unbelievable length of time. I like natural materials, quarry tiles. I would say - I wouldn’t make any grand claims - I’m a good Modern Movement, vernacular architect. It comes to me naturally.’

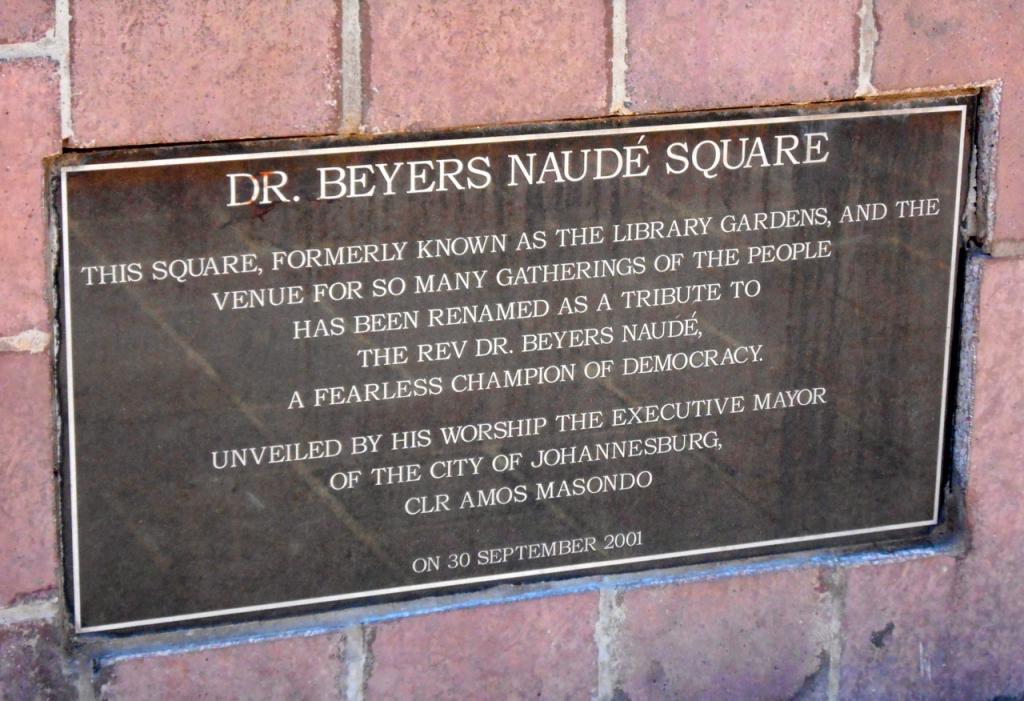

Recently Chipkin was involved as a consultant in urban history, in the controversial redesign of the Beyers Naude precinct around the site of the old Market Square. He knows that in some quarters he’s less than popular for this. Because he’s a conservationist at heart, those buildings that will be torn down to make way for a new precinct, will cause him pain. In earlier years he forbade the removal of a Cape Dutch gable when he was altering Goldenberg’s Kosher Polony Factory in Doornfontein. In his new book, he pays greater attention to Cape Dutch manifestations in the city. But Johannesburg’s centre city, the seat of previous political and financial power structures, where later, trade unions marched and protesters spoke their defiant words, ‘is about to receive an architectural imprint reflecting a hugely significant enlargement of social expectations. . .’ Chipkin argues, ‘that’s the way history works. Johannesburg is not a sacred cow. One constant among most vibrant cities is change. How far should innovation be stifled by heritage? A rigid application of heritage rules results in the embalmed city where change is impossible.’ I sense that Chipkin sees us living on the cusp of history, as we face the inevitable assertion of that oxymoron, new heritage.

Beyers Naude Square from Natal Bank (The Heritage Portal)

Beyers Naude Square Plaque (The Heritage Portal)

His socio political outlook is perhaps emphasized by his view of Sandton, that new seat of financial power. Chipkin admits it hasn’t touched him in any meaningful way, that it means little to him. Borrowing the words of his young architect friend, Sarah Calburn, he dismisses Sandton along with Melrose Arch as a series of ‘private spaces pretending to be public.’ But in his new book, Chipkin acknowledges that Johannesburg is now a city with two distinct CBD’s. In writing about the post-fifties city, he was faced with a Johannesburg far bigger than that represented in the first book. ‘It’s gigantic, it spills over, particularly in the north west, all those town houses! I grew up in Yeoville, trams allowed my penetration of other old suburbs. I considered eating in Hillbrow and going into town as big events. Johannesburg is no longer one thing, no longer a dorp. My second book took much more research.’

Chipkin believes that he, together with other architects of his generation, was influenced by Norman Eaton, whom he calls,‘probably South Africa’s most sensitive architect.’ Chipkin believes that aesthetic influences remain latent in an architect, but often emerge unbidden during design work. He thinks that architect’s work is a response to a hidden agenda; partly as a result of broad schooling, perhaps a turning against things which have been formative. No one thing moulds an architect. And there are the glamour influences of the glossy periodicals acting like siren voices to short-lived exotic ideas.

Speaking again of Eaton the paragon, ‘He didn’t need to take jobs. He was financially independent and if he took them you would wait until he was ready. He’s done some wonderful Pretoria houses. He was all the time exploring a South African idiom. He traveled in Kenya a lot. He spoke about that “wonderful African feeling.” He adored Africa in a non political sense. He acquired many Zanzibari doors as icons. He designed the Netherlands bank building in Durban. It’s a magnificent tropical building with a green glazed, perforated screen which keeps the sun away. It’s got a beautiful garden. You step up to the banking hall past two little fountains; he loved the Muslim use of water; desert people, short of water so the water just tiptoes from the nozzles, it doesn’t emerge with an Italian flourish.

‘Oh yes,’ Chipkin emphasises, reacting to a question about South African architecture in the world, ‘we are recognized internationally! In the thirties, Corbusier, the great French modernist, praised the Transvaal Group of Modern Architecture. The Union Buildings are a great contribution to Imperial Classical architecture. Unfortunately, apartheid prevented Willie Meyer’s RAU building from receiving the international recognition it deserved. Douglas Cowin developed an important regional style. Casa Bedo, in Scott St, Waverley, shows this well. Gordon Leith’s work was ultimately recognized, although the man claimed that his best work was ignored. One of Leith’s greatest, the Reserve Bank building on the corner of Simmonds and Fox Sts, is being restored to its former glory. Leith’s Eloff St entrance and thoroughfare to the old Park Station stands somewhat lonely and forlorn today, but is no less magnificent for that.’

Chipkin enjoys traveling and sharing experiences with Valerie. Every journey is filled with learning and delight. When overseas, he walks, observes and photographs, as he’s done in Johannesburg from his earliest days. When asked about his greatest structural enjoyments he at first refused to answer but temptation overcame him; with almost the same breath he spoke about going ‘berserk’ in St Mark’s Square in Venice. And, ‘as a non believer, experiencing a religious revelation when moving through the Bernini Colonnade onto the piazza of St Peter’s in Rome, traversing the dished floor like the earth’s surface, and then the view of Bramante’s dome elongated towards heaven by Michelangelo.’ He enjoys the Royal Crescent and the rest of peaceful Bath, ‘the rationality and whimsy of London’s Georgian squares and crescents’ and the ‘mesmeric, migraine effect’ of the Firth of Forth Bridge, outside Edinburgh.

He loves ‘the sheer genius of Ndebele rural settlements in their heyday half a century ago, achieved with the flight of human imagination and very little else.’ He reflects that one’s architectural appreciation is a matter of ‘which particular moments one is recollecting.’

Finally we return to the city which has been the setting of his life, the city which has provided him with inspiration and joy. ‘Joburg, what I like about Joburg, is that we haven’t got coherence. Now people will say: “the trouble with Joburg is that we haven’t got this identifiable, flowering culture.” There is no picture of a coherent South African culture!. South African culture is probably a myth. My entire life people have been chasing it. They’re always on the verge of discovering where it is. I don’t believe there’s such a thing. If someone proves me wrong, well that’s great! For me, Joburg is not coherent and I like it, everyone has space. I like the additions from Francophone Africa; also people from Somaliland and Ethiopia. Have you seen the Coptic Monastery, just down the road here? It’s wonderful; quite folkish, not a grand cathedral, but a transposed memory of their traditions. I like the Greek Orthodox patterns. I like the Great Synagogue in Wolmarans St. I enjoy speaking to people on the street. I love the sense of trying again, the tremendous ricochet of ideas, the mix of cultures.’

Chipkin is talking about richness; all those different sights and sounds and smells and ideas we often don’t wish to see or if seen, we don’t care to explore, understand or above all, enjoy. Perhaps a first step for the timid would be to read his wonderfully experienced, researched and written, books.

About the author: Mike has spent most of his life in Johannesburg. He earned his living as a human resources practitioner, first in large companies as a manager, [many stimulating years with AECI] and later in his own small HR consultancy. Much of his later occupational time was spent running training courses for managers on how to handle staff within the framework of South African labour legislation, He wrote and published The Manpower Brief, an IR, HR and sociopolitical newsletter, which was popular in many large companies during the 80s and early 90s. A selection of Briefs were incorporated into the book, People Really Matter published by Knowledge Resources. While working, he wrote several business books, one of which, on negotiating, was a sell-out.

In his ‘retirement,’ he has written extensively about Johannesburg, publishing articles mainly in The Star and Sunday Times. Working with Beryl Porter of Walk & Talk Tours, he developed and guided many walking tours around historic Joburg – Braamfontein, Parktown, Newtown, Centre City, Constitution Hill, Kensington & Troyeville, Fordsburg etc. He regularly took visitors to Soweto. His book Johannesburg Portraits – from Lionel Phillips to Sibongile Khumalo, offered popular biographical essays of well known Joburg citizens. His researched paper on Judge FET Krause who surrendered Johannesburg to Field Marshall Roberts during the Anglo-Boer War, was published in the Johannesburg Heritage Journal. The same journal published his series on famous local paleoanthropologists.

Mike is also a widely published poet. Botsotso recently published his third book of poetry, Poetic Licence. His current historical work, published by co-author Peter Delmar of the Parkview Press, The Johannesburg Explorer Book, takes readers on a journey through old Johannesburg, weaving together a history of events and people, which make this city such a fascinating place. His most recent book, a work of journalism, Twelve plus One, featuring transcribed interviews with Johannesburg poets was issued in 2014.

He lived with his wife Cecily, in a century old, renovated house on Langermann Kop, Kensington. A widower since July 2014, he now lives in Eventide Retirement Village in Muizenberg. He believes himself very fortunate in that his son, daughter in law and grandsons live nearby. His daughter lives in Sydney with her husband and son. In case you’re wondering, Luke Alfred, Mike’s son, is the well-known journalist and author.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.