Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

Contrary to popular belief, Knysna’s colonial history did not begin with George Rex in 1804, but over 30 years earlier with the arrival of a young man from a well-connected family, Stephanus Esias Terblanche. He was granted the grazing rights and permission by the VOC [Dutch East India Company] to live at ‘Melkhoute Kraal gel. in ‘t Niqualand aan de grootse en laatste Valley’ on 14 September 1770. So who was this young man and where did he come from?

By the middle of the 18th century land had become scarce around Cape Town and environs, so colonists gradually moved east in search of new grazing and new opportunities. Among them were Stephanus Esias Terblanche’s father, Pieter Terblanche, son of the French Huguenot, Etienne, and his wife, Petronella, step-daughter of the wealthy Esias Meyer, who had grown up in the comfortable and well established home of Hartenbos, near Mossel Bay. The Terblanches and their family moved from Paarl first to the Gouritz River area in 1750 and finally in 1762 to Rheeboksfontein, between the Great and Little Brak Rivers. The family established a thriving farm which was described in glowing terms by travellers. In 1776 Hendrik Swellengrebel (the Governor’s son) said that Rheeboksfontein was a home with good furniture, food and wine, sizeable lands planted with vines and other crops growing well. When Colonel Robert Jacob Gordon, the military commander at the Cape, as well as a geographer, explorer and artist, was travelling back to Cape Town after his 2nd journey inland in February 1778 he wrote in his diary, ‘…arrived…at nightfall on the farm Rhebokfontein belonging to the older Terblanche. Found every comfort there and in abundance.’ Twenty-five years later when Friedrich von Bouchenroeder, Immigration agent for the Batavian government, visited the area, he said that Rheeboksfontein was the best farm he had seen outside the Cape Town district, with beautiful gardens and fruit trees, a vineyard and good wheat fields and cattle. He reported that during his travels he had passed many farms belonging to the children and grandchildren of the Widow [Petronella] Terblanche and all were industrious farmers and cordial and friendly people.

This then was the environment in which the young Stephanus Esias Terblanche grew up and where he acquired his vision for Melkhoutkraal. As the eldest son of Pieter and Petronella Terblanche, he was the first to leave home and in September 1770 this ‘… very active, clever, and industrious man,’ moved to the uncultivated farmland known as Melkhoutkraal on the south-eastern shore of the Knysna estuary. He was then aged 20, and in October the following year he married Hester, the youngest daughter of Dirk Marx, of the farm Hagelkraal near Mossel Bay. Together they built Melkhoutkraal into ‘one of the most celebrated [farms] in the colony.’

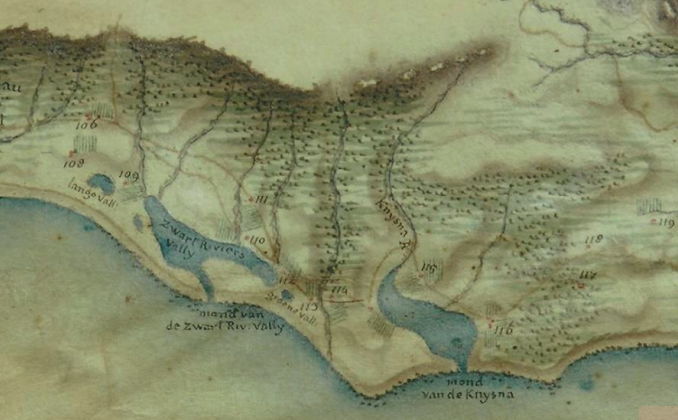

During the 18th century there was a fair amount of travel between the inland areas and centres like Cape Town, Paarl and Stellenbosch. Burghers needed to sell their produce, marry or have their children baptised, as well as go off on hunting expeditions. Overseas explorers and scientists as well as fact-finding Government or Company officials travelled to distant parts of the colony. There were few, if any, inns for such travellers outside Cape Town, so travellers would spend the night at various farms along the way and all were fed and accommodated according to the circumstances of their host. No one was expected to pay for such services. It has been suggested that isolated burghers were not only hospitable, kind-hearted and eager for first-hand news from the outside world, but also wanted to show visitors what successful and prosperous lives they were leading away from the controls of the VOC [Dutch East India Company]. Melkhoutkraal soon acquired a reputation as one of the most hospitable and welcoming farms in the area, along with Hartenbos and Rheeboksfontein. By 1780 Stephanus had also acquired Welbedagt and Sandkraal, later to be named Eastford and Westford by George Rex. In 1774 Stephanus’s younger brother, Pieter, had been granted permission to farm at Buffelsvermaak (on the eastern side of the Goukamma River). Thus by 1790 when Lieutenants JJ Friderici and J Jones produced their map of the Southern Cape Coast for Governor Van de Graaff, Stephanus and his younger brother Pieter were in possession of all the land around the Knysna lagoon, from the Goukamma River right round to the Eastern Head.

Extracts from the 1790 map by Friderici and Jones (Cape Archives)

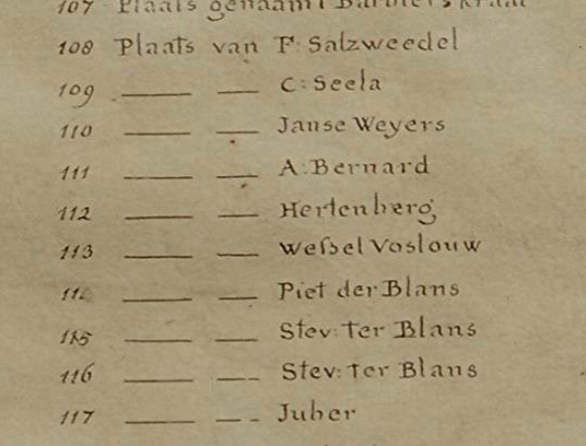

How do we know about Melkhoutkraal and other successful farms in these outlying areas? Firstly, we have the accounts published by early travellers who had stayed at these farms. However these travellers did not often describe the actual farmhouse or its contents in much detail, nor did they make drawings of the settlers’ homes. An interesting exception is the ‘Panorama of the Knysna River and the defile through which it flows into the sea’ drawn by Colonel Gordon in 1778, which includes a sketch of Melkhoutkraal. Gordon recorded in his diary of 16 February 1788 that after travelling ‘…over large hills and deep kloofs with many turns… I reached the Knysna’s mouth on the farm of Stephanus Terblanche… I took bearings on and drew a view of the Knysna.’ At this stage Melkhoutkraal comprised only three buildings (a farmhouse with a chimney surrounded by a werf and two outbuildings with three other enclosed areas – possibly kraals for animals).

Extract from the 1778 painting by Robert Jacob Gordon showing the Melkhoutkraal Farm (Painting held in the Rijksmuseum)

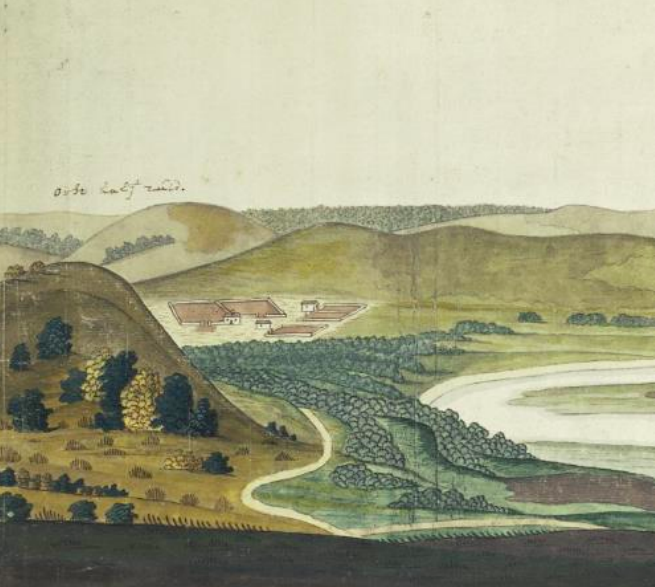

A second source of information is the archival records which list the contents of homes and provide us with wonderfully detailed glimpses of the owners’ way of life. As was required by Roman-Dutch law, later to be continued by the British authorities during the First British Occupation of 1795-1803, the assets of a deceased estate had to be fairly distributed between the surviving spouse and children. The assets had first to be listed in a room-by-room inventory followed by an auction sale held at the property. We do not know exactly when Stephanus Terblanche died, or the circumstances of his death. No death notice has been located, so perhaps he died during a hunting expedition, as did his grandfather, Etienne. The only clue comes from Petronella Terblanche’s (Stephanus’ mother) will, drawn up in May 1795, where he is not listed as a beneficiary along with his siblings, but instead his nine children (five sons and four daughters) are listed in his place, thereby indicating that he had already died, possibly in 1794.

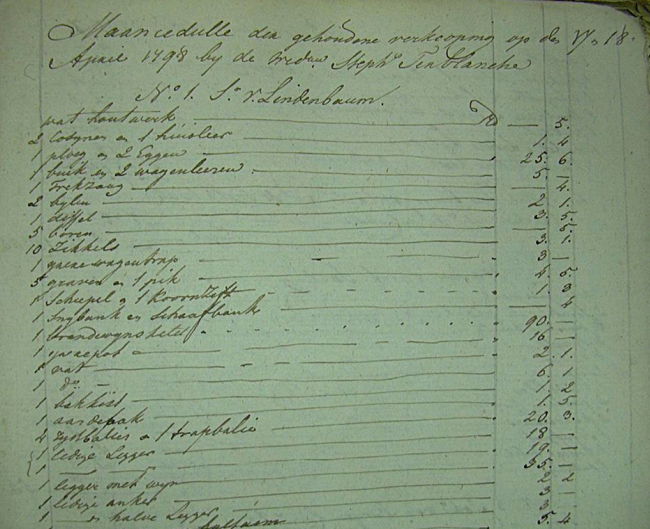

On 16 April 1798 an official inventory of Melkhoutkraal was drawn up. From this we discover that the farmhouse consisted of four rooms, probably in a T-shape or an L-shape design, as was the style of many farmhouses in the Mossel Bay area, such as those of his father and maternal grandfather. The Voorhuis or reception room was in the centre with a room on either side; and a kitchen at the back, with a door leading from the Voorhuis. There were now four outbuildings – Winkel, Klein Pakhuis, Stookhuis and Kelder, surrounded by the Werf or farmyard.

The furniture and tableware listed in the different rooms gives some indication of how the rooms were used and how prosperous the family was. Farmhouses stayed more or less the same size during the 18th century, so it is important to consider other possessions such as slaves, livestock, grain and wine stock. Slaves were major assets in the rural areas.

Inventory List (Cape Archives)

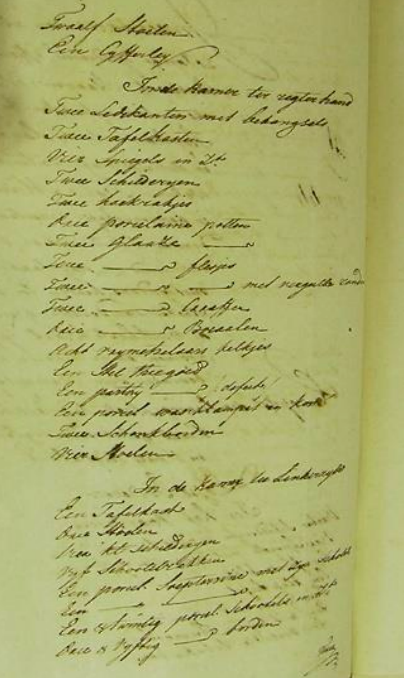

The Voorhuis was used as the entrance hall and reception room as well as the eating and drinking area. Melkhoutkraal furniture listed in the Voorhuis comprises a gate-leg table, at which the family and guests could eat; two small tables and 12 chairs. There were also four mirrors with gilt frames, 14 paintings and a Friesland clock – unusual items for a rural farmhouse so far from Cape Town. Mirrors with ornamental frames were status objects even in Cape Town. Then there is a brass (witkoper) tea machine, which would have included a kettle, urn and konfoor (a metal brazier containing burning charcoal), and probably stood on one of the small tables. There are many descriptions by early travellers of tea-drinking, for example Robert Semple wrote - ‘In the day time in one corner of this hall stands a small table, and beside it sits the mistress of the family with her feet upon a stove… Upon the table is a brazen urn filled either with coffee or hot water for tea, and this continues in use the whole day…’. An abacus or counting frame is listed, which probably stood on the other small table, as did a lacquered tobacco box (an import from the East). Interiors were often rather dark so the mirrors with gilded frames would have added light to the room, as would the brass tea machine – clearly a status item. It is interesting to see that that no tableware or glasses were kept in the Melkhoutkraal Voorhuis. Possibly the two silver candlesticks and a silver sugar bowl listed separately at the end of the inventory (as was the custom for silver items) could have been kept in the Voorhuis as they were important status symbols as well as being useful.

The room on the right of the Voorhuis was a multi-purpose room. Here we find listed two beds with hangings and posts, a porcelain wash basin, four chairs, and two chests of drawers, possibly for storing clothes and linen although none are listed. There were also two corner cupboards, probably for storing the drinking glasses, tea set and porcelain bowls along with two trays for carrying tableware to the Voorhuis. The variety of glassware is interesting — four glass flasks — two with gilt decoration, two glass carafes, three large drinking glasses (bocaalen) and eight stemmed wine glasses. We learn from the Auction list (see below) that two of the flasks were made from green glass. Two mirrors and two paintings hung on the walls.

The room on the left of the Voorhuis had a plain stretcher bed with no hangings or posts (kadel), three chairs, a chest of drawers and five shaving basins. A large amount of porcelain tableware, including serving dishes (21), soup tureens, bowls and plates (35) was kept in this room. Pewter items included a coffee pot, tea machine, pots and spoons (24), as well as steel forks and knives (24 of each). This room also had four paintings.

The kitchen furniture consisted of a table, a food cupboard and a dresser for storing pots and pans. A wide variety of pots and pans is listed made either from iron, copper, earthenware or wood and a little pewter. This shows clearly that copper utensils were primarily kitchenware while porcelain was highly prized and kept in the main part of the house. Lighting was provided by four copper candlesticks and an old lantern. The kitchen was the only room with a fireplace and there were chimney chains for smoking hams and other equipment like iron hooks and fire tongs. A pestle and mortar, grater, colander, waffle iron, grid iron and butter churns are also listed.

The four outbuildings described as Winkel, Stookhuis, Klein Pakhuis and Kelder, contained farming equipment as well as many carpentry tools including a carpenter’s bench, bench vice, measure and gauge, a variety of saws and Stinkwood planks — indicating that Terblanche was very involved in the timber business, as were many other farmers in the district. The early travellers often commented on the ‘noble’19 and ‘lofty’ trees in the beautiful indigenous forests found between Mossel Bay and Plettenberg Bay. Dirk Gysbert van Reenen, who accompanied General Janssens on his journey in 1803, said that the forests contained at least twenty different kinds of wood, ‘such as iron, assegai, stink, yellow, beech, and other wood, all very useful for different purposes.’ Stephanus’ brother-in-law, Johann Friedrich Meeding, had been appointed Postholder at Plettenberg Bay in February 1787 and between August 1788 and September 1792, Stephanus, along with his brother Pieter of Buffelsvermaak, was a member of the group of local farmers who were contracted to supply timber to the Company Post at Plettenberg Bay for shipment to Cape Town. There was a particularly big demand for timber in Cape Town at this time as a new hospital was being built.

The presence of two Brandy kettles, a half legger of brandy, five leggers of wine and two vats of vinegar, points to another aspect of farming activities at Melkhoutkraal. Apparently brandy was often made from peaches and many of the farms in the area had large peach tree orchards.

Although some travellers considered that the grazing in the area was not suitable for sheep and cattle, there were nevertheless both cattle (152) and sheep (508) on the farm, as well as horses (14 and 5 foals) and oxen (42).

A total of 12 slaves was listed - seven men and three women, with two children. Only their names and country of origin are listed, not ages or occupations. Four were from Mozambique, one from Madagascar, one from Mallabar (west coast of India), one from Batavia and five from the Cape. Generally slaves from Mozambique and Madagascar were used in the fields as they were considered to be well suited to heavy farm labour. The others could have been craftsmen of various sorts and the women would have worked in the kitchen and looked after the children.

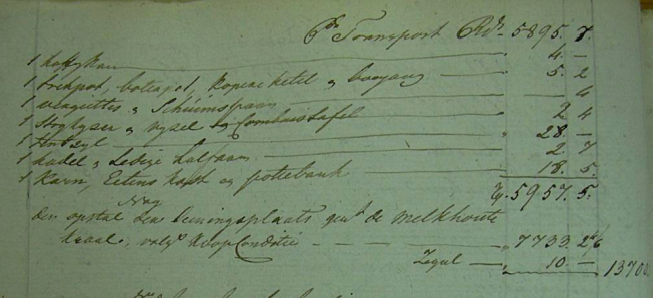

An auction sale was held at the farm on the two days following the inventory process, on 17 and 18 April 1798. The auction roll shows who bought what and how much they paid for it. Here we discover that a ‘Johannes von Lindebaum’ bought the homestead of Melkhoutkraal for 7,733 Rixdalers, and spent 5,957 Rixdalers buying a good deal of furniture, tableware, eight of the slaves, animals including most of the sheep, and that he planned to continue making wine and brandy as he bought a brandy kettle and equipment for pressing grapes as well as empty wine casks. Members of the Terblanche family as well as other farmers from the district also bought a variety of items. Local farmers from Mossel Bay to Plettenberg Bay included Jan Jarling from the east bank of the Keurbooms River; Daniel Marais from Mossel Bay (who bought the silver candlesticks (RD 54) and sugar bowl (RD 25)); Cornelius van der Watt of Stofpad; Wessel Vosloo the elder of Ganzvlei and his son; Manh. Hans Abue, the Postholder at Mossel Bay; members of the Barnard family from north of Swartvlei; and Cornelius Botha the elder, from the Piesang River. A total of RD 17,721 was realised at the auction. The slaves realised RD 5,895; the animals RD 2,045; the wine and brandy RD 317 (including two brandy kettles).

Stephanus Terblanche’s sons bought various items — Johan Ernst, the eldest, who had recently married and farmed at Welbedagt, bought farming equipment, animals, furniture, a little tableware and a slave woman, Rosette van de Kaap. Stephanus Esias (2nd son) bought the ox wagon, animals including 50 sheep and the slave Jepetha van de Kaap, as well as the two green glass flasks. Petrus (3rd son) bought cattle and oxen and the slave Lindor van de Kaap. Salomon, aged 15, who was to marry in 1807, only bought cattle. Daniel Petrus Marais, married to Stephanus’ eldest daughter, Dorothea Maria, bought tools, the abacus, a tea set and the slave Avontuur van de Kaap. Stephanus’ brothers Johan Gerhard of Zorgfontein bought wine, two of the paintings and the brass tea machine (53 Rixdollars); Pieter of Buffelsvermaak bought only cattle, horses, oxen, sheep and two vuurtessies (coal holders).

Three weeks after the sale the new owner Johannes von Lindenbaum (aged about 37) married Stephanus Terblanche’s widow, Hester, in Paarl on 13 May 1798. At that stage her future would have been rather uncertain. She was 51 years old and had four children under the age of 18. Her two oldest children were already married, leaving the next oldest – Stephanus Esias aged 20, who was to marry the following March, and Petrus (18), who was to marry his cousin Petronella in May 1800, as the only children able to make a substantial contribution to running the farm. If married to the new owner she would be able to stay on at Melkhoutkraal and provide a home for her young children.

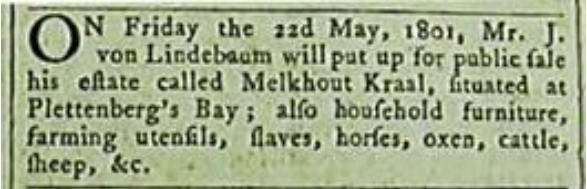

Von Lindenbaum had previously been employed by the VOC as an assistant (the 2nd lowest rank) and in February 1793 had married Catharina Machtelda Bergh, the youngest daughter of a high-ranking VOC official at the Cape, Oloff Martini Bergh. Catharina had given birth to a daughter in March 1793, but had died in October 1796. Von Lindenbaum had thus inherited sufficient money to purchase a farm like Melkhoutkraal. It was fairly common practice at the Cape for young men to marry wealthy widows and continue running their farms. However, for unknown reasons, only three years later, on 18 April 1801, the Cape Town Gazette announced that ‘On Friday 22 May, Mr J von Lindenbaum will put up for public sale his estate called Melkhout Kraal, situated at Plettenberg’s Bay; also household furniture, farming utensils, slaves, horses, oxen, cattle, sheep etc.’

The advert of sale (Cape Town Gazette)

Extracts from the Von Lindenbaum auction roll (Cape Archives)

On 22 May 1801 the recently arrived English merchant Richard Holiday purchased the farmstead for 26,000 gulden. Richard Holiday was in partnership with John Murray, one of the first British merchants to arrive at the Cape. Murray knew the Knysna area well as he had been involved in the coastal trade since 1797 with his brig Alert, skippered by the Scottish master-mariner James Callander, and had a loan farm and trading store at Mossel Bay.

The auction sale was held at Melkhoutkraal on 22 and 23 May 1801 and those who bought items of furniture, farm equipment etc. are listed in the auction list. Items which had not appeared in the earlier 1798 list included two pull-up or Venetian curtains, two tea tables (these usually had a drawer in one side, and the tea machine stood on the top) and seven wooden storage chests (kists), which were used for storing possessions and as seats and tables. Although the farm had been sold to Holiday, the widow Hester Terblanche (now Mrs von Lindenbaum) and her unmarried Terblanche children continued to live there. When the young Englishman Robert Semple stayed at the farm in August 1801 on his way to Plettenberg Bay, he described them as ‘…this hospitable family…In an hour we were no longer strangers, and on retiring to rest, it seemed as if we were in the bosom of a family…now met after a long separation.’32 Semple also described going hunting and fishing with the eldest remaining son, Salomon, then aged about 17. His four elder siblings had all married by 1801.

It is doubtful whether Richard Holiday, the new owner, ever lived at the farm - perhaps he had been persuaded by Murray to purchase it as an investment. However Holiday’s investment was short-lived as he died in July 1802 and in October 1802 there was an incursion by a band of Xhosa and Khoi into the district. This was one of several incursions in the district which occurred between 1799 and 1803. Many farms in the Plettenberg Bay and Knysna areas, including Melkhoutkraal, were destroyed, set alight, and cattle and sheep stolen. The inhabitants fled to safety and four Plettenberg Bay farmers were killed during an ambush on the road to Knysna at Die Poort while fleeing to Mossel Bay. Their wives and children were captured but later released. Several accounts mention a Lindenbaum being with the party, but describe him as taking one of the women to Cornelis van der Watt’s farm, Stofpad, during the ambush. Another account says he died on the road between Plettenberg Bay and Knysna. It is not clear whether this Lindenbaum was the previous Melkhoutkraal owner. A document recently found in the Cape Archives indicates that the Melkhoutkraal von Lindenbaum had died by 1804.

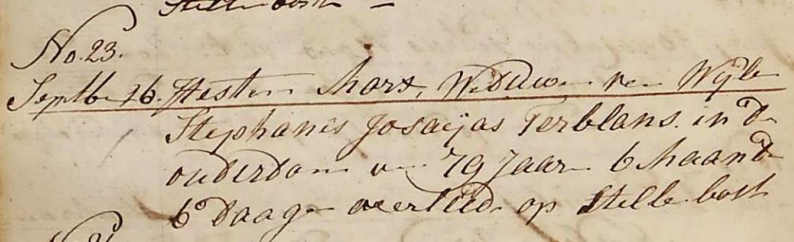

Hester and her family probably fled to her mother-in-law’s farm Rheeboksfontein, where refugees were staying when Governor Janssens’ party spent a night there in April 1803. In December 1803 Hester acquired the homestead of the loan-place Groote Hoogekraal (on the western side of the Kaaimans River) for RD 1,000, but in May 1804 sold it to Daniel Frey for the same price. Nothing more is known about Hester until her death. She died in 1826 at Zorgfontein, (near Rheeboksfontein) the farm belonging to her brother-in-law Johannes Gerhardus Terblanche, at the age of 79. She is described as the widow of the late Stephanus Joseyas Terblans, with no reference to her marriage to von Lindenbaum.

Record of the death of Hester Marx (NGK)

We have reports from three travellers who passed through the area in 1803. Two were members of parties of Batavian Republic officials who, shortly after arrival, set out to inspect the colony, recently acquired from the British under the terms of the Treaty of Amiens, for themselves. W.B.E. Paravinci de Capelli, aide-de-camp to the new Military Governor, General Janssens, described the pleasant evening the Governor’s party spent at Rheeboksfontein in April 1803, where many refugees were staying. He found an old violin which he played while the young people danced late into the night.

Henry Lichtenstein, a member of Commissioner-General de Mist’s party, described their evening at Rheeboksfontein in December of the same year by praising the evening meal and saying that their hostess Widow Petronella Terblanche ‘was celebrated in the country for her excellent table.’ He also mentioned a guitar made of African ash-wood, which ‘…is a favourite among the colonists and is almost always to be seen in the houses of substantial people’ - possibly Paravicini’s violin?

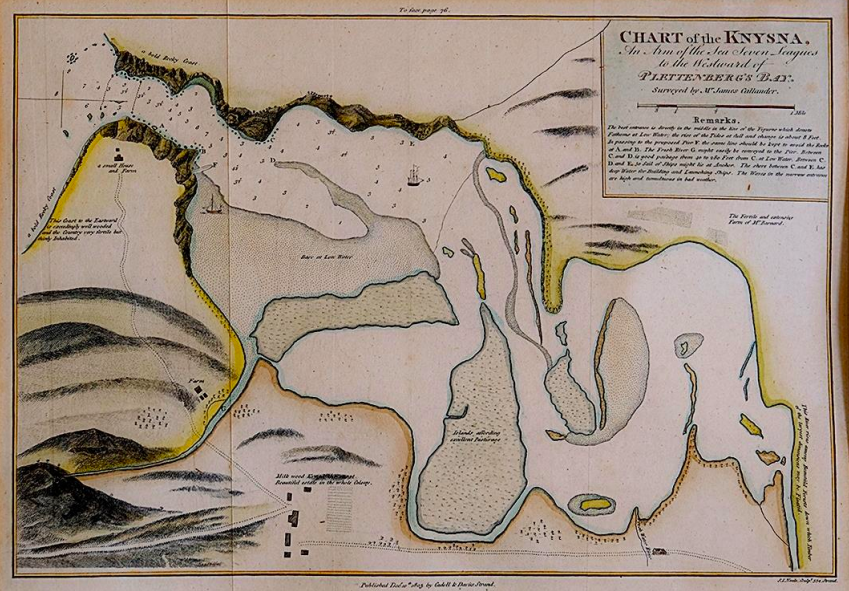

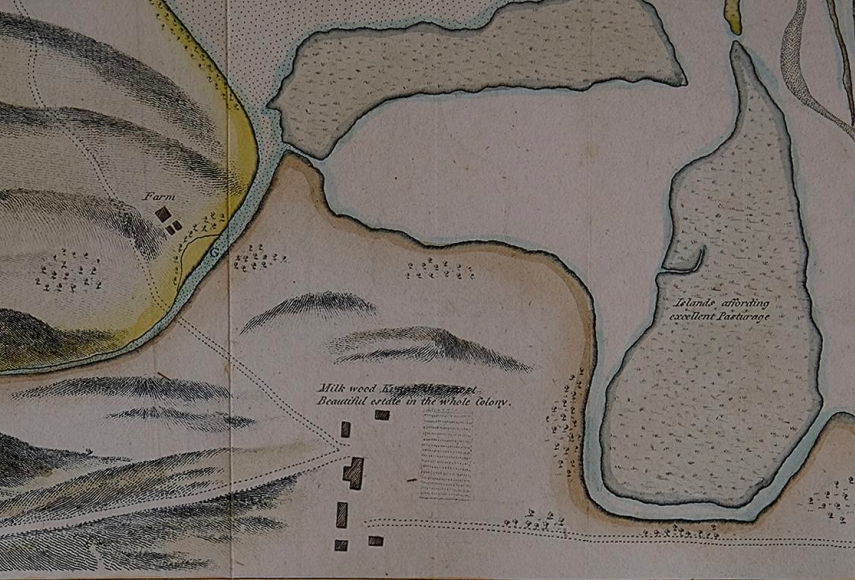

Both parties stopped at the ruins of Melkhoutkraal when they continued their journeys. Janssens’ party had their midday meal there under the shade of the orange trees. Another member of Janssens’ party was the burgher Dirk Gysbert van Reenen who described Melkhoutkraal as ‘…altogether destroyed and burnt [with]…a vegetable garden, a vineyard and an orchard, all laid out in orderly fashion.’ He described the meeting with James Callander who ‘…presented the Governor with a map [he had drawn] of the Bay showing its lie and depth, as well as of the river, certifying that the latter was quite navigable…’. This map features a tiny plan of ‘Milk wood kraal the most Beautiful estate in the whole Colony’, with the farmhouse and now five outbuildings clearly drawn. Callander, who was living in a small wooden cabin on the Eastern Head, had been asked in 1798 by the new British Governor, Earl Macartney to report on the forests, bays and rivers of the region. From 1800-1802 he was appointed Inspector of Government Woodlands. Callander believed that ‘the whole of the woods from the Cayman’s River, eastward to the Nysna should be in reserve for the Government, as all the woods in that space contain vast abundance of valuable timber..’

An early Chart of the Knysna drawn by James Callander

A detailed view of the Melkhoutkraal buildings

Lichtenstein described in more detail the sad state of the farm when he stopped there in December 1803. ‘We scarcely found a place among the ruined walls where we could make a fire.’ He described the vegetables growing wild, a ‘red deer’ in the vineyards eating the grapes; ‘hedges of roses and jessamine’ ‘the orange trees bent under the weight of their fruit, and an endless number of peaches, apricots, almonds and bananas.’

Another visitor in 1803 was the Dutch immigration agent, Friedrich von Bouchenroeder, who had arrived at the Cape in May. He soon set out to explore the eastern districts of the Colony with a view to establishing settlers at Plettenberg Bay and the Port Elizabeth region. When he reached Melkhoutkraal he was sad to see the destruction of ‘one of the most beautiful farms in the Colony, which had had a spacious homestead and stables.’ He described the orange trees as being full of fruit and said that there were other valuable fruit trees and vegetables, which had been kept in good order. The farm had also been a good wheat and cattle farm. Instead of being warmly welcomed by the family as would previously have happened, Von Bouchenroeder and his party had to spend the night in the remains of the ‘koren huisje’.

In May 1804 Melkhoutkraal was bought by George Rex from the estate of Richard Holiday (John Murray being the executor). George Rex and his extended family arrived in December and soon set about rebuilding Melkhoutkraal and restoring the extensive farmlands as well as the lucrative timber trade. A new chapter had begun.

Click here to see original article including footnotes.

Acknowledgements: My grateful thanks to Margaret Richards for her invaluable help with both the original research as well as numerous editorial improvements; to Philip Caveney for ensuring that the story was made available to a wider audience and for sharing his discoveries in Col. Robert Jacob Gordon’s papers and paintings in the Netherlands; and to Margaret Parkes for her encouragement over many years.

About the author: Leonie has a long term interest in the history of Knysna. She is a researcher, editor and indexer, and a former librarian in charge of the Manuscripts & Archives Department at the University of Cape Town Libraries. Leonie moved permanently to Knysna from Cape Town in 2003. She is a member of the Knysna Historical Society.

References

- Brink, Y. They came to stay. Discovering meaning in the 18th century dwelling, Stellenbosch, 2008

- Callander, J., Diary 1798-1800, BO 101 & 235 Cape Archives

- Friderici, JJ and J. Jones, Caarte van den Zuydelyken oever van Afrika, 1789-1790, M4/113 Cape Archives

- Gordon, R.J. Drawings and Travel Journal 1778, www.robertjacobgordon.nl

- Lichtenstein, H. Travels in Southern Africa, 1803-1806, Cape Town, 1928

- Malan, A. Households of the Cape, 1750-1850: inventories and the archaeological record, PhD thesis, UCT, Cape Town, 1993

- Mentzel, O.F. A geographical-topographical description of the Cape of Good Hope, 3v., Cape Town, 1921

- Paravicini di Capelli, W.B.E. Travels in Southern Africa, 1803-1806, Cape Town, 1928

- Semple, R. Walks and Sketches at the Cape of Good Hope, Facsim. ed., Cape Town, 1968

- Sleigh, D. Die Buiteposte: VOC-Buiteposte onder Kaapse bestuur, 1652-1798, Pretoria, 2004

- Storrar, P. George Rex: death of a legend, Johannesburg, 1974

- Storrar, P. Portrait of Plettenberg Bay, Cape Town, 1978

- Swellengrebel, H., Journaal eener Landtogt…enlangs de Suid Oost Kust, 1776. MS. A447 Cape Archives

- Terblanche, P.S. Terblanche-land. Stamvader – Etienne Terblanche, sy nasate en hulle grondbesit, 1701-1880, 2006

- Van Reenen, D.G. Die Joernaal, 1803, Cape Town, 1937

- Von Boucheroeder, B.F. Reize in de binnelanded van Zuid-Afrika, 1803, Amsterdam, 1806

Illustrations

- Panorama of the Knysna River and the defile through which it flows into the sea, 16 February 1778, drawn by R.J. Gordon. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam RP-T-1914-17-40

- 2a-b. Friderici map showing the farms and farmers’ names around the Knysna lagoon, 114, 115, 116. Cape Archives M4/113

- Detail from the panorama showing Melkhoutkraal in 1778.

- Page from the Melkhoutkraal Inventory, 1798. Cape Archives MOOC 8/22 no.44

- Advert for the sale of Melkhoutkraal in 1801. Cape Town Gazette, 18 April 1801

- 6a-b. Extracts from the Auction list of Melkhoutkraal illustrating Johannes von Lindenbaum’s purchases. Cape Archives 1/SWM 12/55

- Death notice of Hester Marx, 1826, at Zorgfontein. Burial Register, NGK, Stellenbosch

- Chart of the Knysna, by James Callander, published in 1805.

- Detail from the Chart of Knysna showing Melkhoutkraal in 1803. Revision 20.4.21

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.