Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

On a recent visit to the Resource Centre of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation at the Holy Family College, Oxford Road, Johannesburg, a new acquisition was on display, namely a brass name plate from the architectural firm “Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner ARIBA Architects“. The brass plaque had been donated to JHF by Ronald Sutherland of Durban.

Holy Famly College (The Heritage Portal)

It is a beautiful solid brass plate and is from the Durban offices of Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner. It was originally in position at their offices on the 3rd floor, Yorkshire House, Field Street Durban and dates from at least as early as 1935 probably earlier.

Here is a wonderful memento of an architectural practice with a long history and a strong presence in Johannesburg and Durban with some fine buildings erected in Cape Town, Kimberley, and in other South African towns. Clive Chipkin in Johannesburg Style describes the firm as “a household name in the 1930s.”

Book Cover

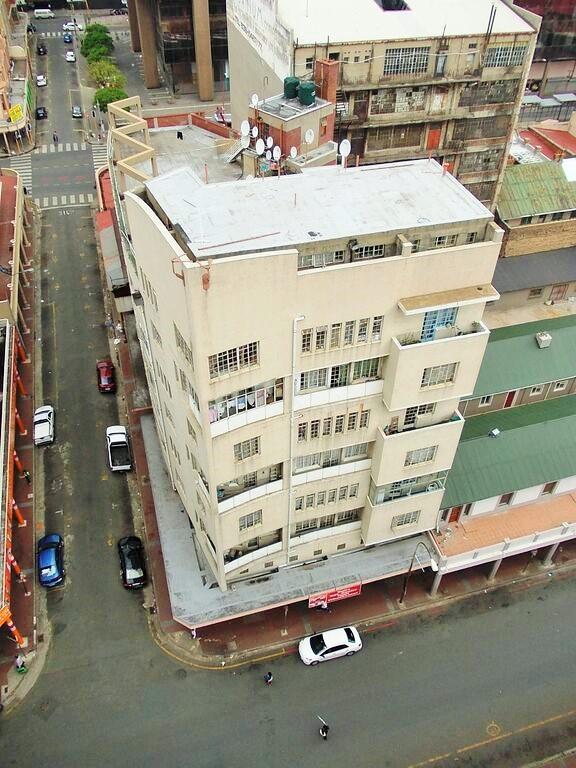

Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner was among the most successful architectural firms of the interwar period in South Africa. Their reputation was solid and their output prodigious. They designed synagogues (e.g. the Benoni synagogue of 1933-35), cinemas (the Plaza cinemas around the country - 1931 onwards), modern homes (some still survive in Parkview and in Houghton), skyscraper office blocks (The Lewis and Marks building in Johannesburg and the Trust Building - later called Westgard House in Durban - but demolished in the early 1990s), and stylish large apartment complexes (Constantia Court in 1934, near Joubert Park is still extant, and the two Durban blocks: Albemarle Court and Grosvenor Court). Clive Chipkin explained that the essence of the Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner practice was that it was a professional firm and strongly motivated (personal email to Kathy Munro).

Lewis & Marks Building, Johannesburg

Albermarle Court

Grosvenor Court

The partnership of three men - Hermann Kallenbach, Alexander MacFarlane Kennedy and Arthur Stanley Furner lasted from 1928, when Furner joined the firm until the death of Kallenbach in 1945. The firm made a significant contribution to the built environment of the principal cities as South Africa emerged from the depression and transitioned from rather old fashioned arts and crafts or Gothic church styles in building and embraced modernism, or as we call it today, Art Deco architecture.

Names on a brass plate are no more than a clue to an intriguing story of three men who were in partnership for approximately two decades of their professional lives. They were all immigrants to South Africa. Their full names and dates: Hermann Kallenbach 1871 – 1945, was the oldest of the trio - German but Lithuanian born Jewish pioneering architect in South Africa; Alexander McFarlane Kennedy – 1879 – 1967, Scottish born but arrived in South Africa as a child; and Arthur Stanley Furner – 1892-1971, of English descent, who came to South Africa in 1925.

The story starts with Hermann Kallenbach, who arrived in South Africa in 1896 from Europe. He trained as a stonemason, a carpenter and an architect. He studied in Tilsit, Strelitz and Stuttgart and in the early 1890s worked as a draftsman in the office of an architect in Stuttgart. Following a year of compulsory service in the army where he was an officer in the Royal Engineers in Munich and on the completion of his architectural studies he immigrated to South Africa to join his maternal uncles, by the name of Sacke. His background, training and design approach was entirely European. He established himself as an architect in Johannesburg within a year of his arrival and was first in partnership with a certain Phillips. Then came the disruption of the Anglo Boer War. Kallenbach appears to have departed for Durban and probably overseas travels. But there was no further mention of Phillips after 1903. Kallenbach then partnered with A. Reynolds, between approximately 1903 and 1907 or 1908. Kallenbach’s early achievements included a number of Dutch Reformed churches around the country and in Johannesburg, The best known works of this partnership were the Fairview Dutch Reform Church, in Op den Bergen Street and the St Andrews Presbyterian Church on Commissioner Street. Both churches are still extant and still serve as places of worship but for new communities.

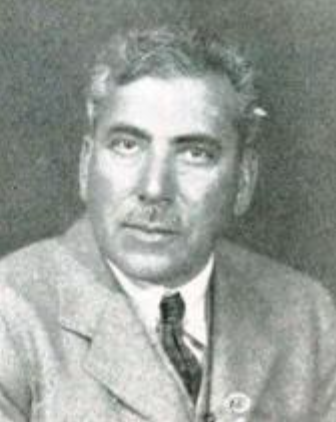

Hermann Kallenbach, from Johannesburg Who's Who 1928-29

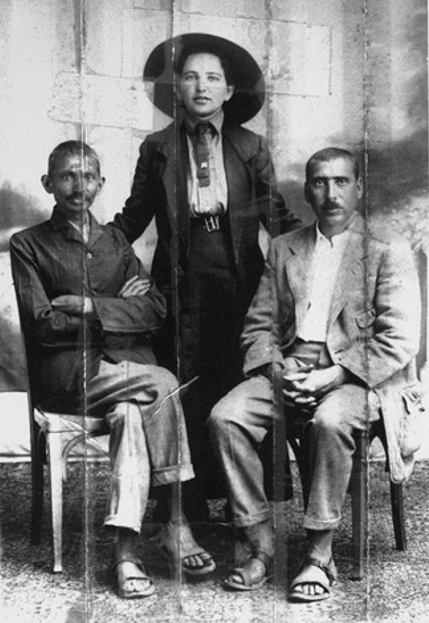

In parallel with his architectural practice Kallenbach established a firm friendship with Mohandas Gandhi with who he first had business dealings in 1903, but from 1904 their friendship became personal and intimate as they shared ideas and books. They stimulated one another intellectually and then from 1907 until early 1913 shared homes first in Orchards, Johannesburg and then at Tolstoy Farm. Named for the great Russian writer and social reformer, Tolstoy Farm situated near Lawley to the South of Johannesburg was purchased by Kallenbach in 1910 and made available to the passive resisters nurtured, schooled and led by the charismatic Indian lawyer Gandhi. There was a mutual attraction but Kallenbach was increasingly drawn to Gandhi’s evolving political thought and philosophies about life.

Satyagraha House, Orchards (The Heritage Portal)

A friendship with Gandhi did not preclude Kallenbach finding a new professional partner in the business of architecture. Alexander McFarlane Kennedy was Kallenbach’s next partner and they worked together for a few productive years between 1909 and 1912. These were the years that produced the Hebrew High School in Wolmarans Street and the Greek Orthodox Church as well as the First Christian Science Church, in Banket Street a stone’s throw from one another. Kallenbach chose the site of the planned new synagogue on Wolmarans Street, the Great Synagogue, but though the partnership entered the competition for the design of the edifice (and there were 22 entries), the winner was Theophile Schaerer a Swiss architect. Kallenbach was bitterly disappointed.

First Christian Science Church (The Heritage Portal)

The early career of Alexander McFarlane Kennedy is still something of a mystery. He was of Scottish origin. He was born in Stirling, Scotland in 1879, making him some eight years younger than Kallenbach. He was the son of John Kennedy and Isabella McFarlane Kennedy and had three brothers and one sister. Genealogical records sourced from Wikitree show that a Mrs. Kennedy together with three children including our Alexander came to South Africa on the Norham Castle in 1884. Kennedy was described as a pioneering architect of Johannesburg and it would seem that he was in Johannesburg in the 1890s; but we know nothing about where he trained as an architect and there are no British architectural educational records. In later years he was known as the quantity surveyor in the KK&F firm, so the question arises, did he train as an architect or was his apprenticeship in fact in quantity surveying?

Kennedy married Annie May Hastings in 1909 and they evidently settled in Johannesburg. An early valuation roll for Orchards show that he had a house in this suburb in 1913 when he owned and had built a house on Stand 109, but by 1925 this property was owned by Dr A D Bensusan. (Johannesburg Valuation rolls, 1913 and 1925)

There was an interesting dynamic in the Kennedy-Kallenbach early partnership. In 1911 when Kallenbach spent several months visiting his family in Europe, Kennedy was left to run the Johannesburg practice and when Kallenbach wished to extend his stay abroad he sought the permission of Kennedy and Gandhi. From Gandhi's letters as well as Kallenbach's diary of 1912 Kennedy also knew Gandhi very well. It is also evident from letters and diaries that relations between Kallenbach and Kennedy did not always run smoothly and we catch a glimpse of Gandhi intervening to try to settle the difficulties between the two partners. It would appear that when Kallenbach and Kennedy parted company in 1912 it was with mixed feelings. (The Gandhi and Kallenbach letters and archives are held in Israel and India).

The second decade of the twentieth century were years of turmoil and the architectural partnership terminated. Kennedy left Johannesburg for Canada in the latter part of 1912 and went in for fruit tree cultivation or “orcharding”. Later Kennedy returned to his profession and worked in the office of the well-known Canadian architectural practice of A R Cobb. Andrew Randall Cobb was a respected Canadian architectural firm in Hallifax, Nova Scotia, Canada; an extensive collection of architectural drawings prepared by A.R. Cobb between 1910 and 1943 is now held at the Public Archives of Nova Scotia in Halifax. (source – the Biographical Dictionary of Canadian architect).

From the latter part of 1913 Kallenbach gave up architecture to embark on a spiritual journey with his great friend and “soulmate” Mahatma Gandhi, first in the great protest for Indian Civil rights in 1913 and then to leave South Africa to accompany Gandhi to India via England when political victory appeared to be at hand in 1914. However on arrival in the UK the outbreak of the First World War forced a change in Kallenbachs’s plans. In England Kallenbach whose nationality was technically German was not granted the British nationalization status he sought. He found himself stranded in London and declared an enemy alien. In 1915 following the sinking of the Lusitania, Kallenbach was interred on the Isle of Man for two years at Knockloe and at the Douglas camps. He was released in 1917, before the end of the war, and returned to his family in Germany who he had not seen since the 1911 visit.

Gandhi and Kallenbach in 1913

It was only in 1920 that Kallenbach returned to South Africa and resumed his career in architecture. Kennedy too returned from Nova Scotia in Canada and joined Kallenbach in a resumed partnership. Kennedy’s Canadian years, enhanced the experience that Kennedy brought back into the practice. The Kallenbach, Kennedy partnership was Johannesburg based but once Kennedy had joined Kallenbach it did not take long for a Durban office to be established and in about 1924 Kennedy was listed as resident in Durban where for a time he ran the business and became a registered member of the Natal Provincial Institute of Architects and remained a member until 1946 the year after Kallenbach’s death.

Kennedy’s strength in the interwar period lay in quantity surveying. Chipkin thinks that he may not have been an architect, but remembers him as “a pipe smoking Quantity Surveyor“. He was the man who calculated the quantities on all the working drawings. Chipking adds “spilling burning tobacco onto some of the drawings, providing strength to the firm with a sense of realism based on cost estimates and quantities and not on rough approximations. That is a real advantage for a professional practice-a rare ability” (personal communication of Clive Chipkin to K athyMunro).

The firm also worked in Pretoria. Clive Chipkin remembers: “My Uncle Solly Unterhalter (who used KK&F in Pretoria) introduced me to old man Kennedy, who was a stalwart of the practice, and clued up on financial matters; that is my impression. Their engineers were often A S Joffe who were also cost disciplined.”

Remarkably, Kallenbach whose life choice and career direction had wavered in 1914, and led to a disastrous incarceration, rebuilt his life and his position in Johannesburg society after 1920. His is a story of a fateful friendship with Gandhi, elated and soaring commitment and sacrifice to the cause of Indian Civil Rights in South Africa. South Africa became the training ground and place of experimentation of tactics that Gandhi later used to challenge the British in his fight for Indian independence. Kallenbach made an extraordinary contribution to the shaping of the Gandhian philosophy and political tactic of Satyagraha. He partnered Gandhi in the development of Tolstoy Farm, an idealistic community of the committed and an experiment in self-sufficiency; Kallenbach bought the 1100 acre farm and made it available for the experiment with Gandhi. It lasted only two and a half years before Gandhi departed for Phoenix, Natal in January 1913.

Statue of Gandhi and Kallenbach (Martynas Ambrazas)

Prior to 1914 Kallenbach and his earlier partners were known for their successful largely religious architecture. He gave it all up for the life he chose with Gandhi. This is a fascinating human story of life’s choices and how success can turn to failure and tragedy, but that life offers second chances and new beginnings, renewal and hope.

Arthur Stanley Furner did not join the firm until late in 1928. He was the third and youngest architect of the partnership. Furner came to South Africa from England. He trained as an architect in London between 1910 and 1913. During the First World war he enlisted in the army and saw service in India. In 1925 Furner took a senior lectureship in the Department of Architecture of the University of the Witwatersrand under the headship of Professor Geoffrey Pearse. Although Furner spent no more than three and a half years at Wits, his influence was seminal because he was reputed to have introduce the idea of modern architecture to South Africa and shaped the thinking of later South African architectural luminaries, Rex Martiennsen, Gordon McIntosh and Norman Hanson. Chipkin describes the atmosphere at Wits at the time as one where students caught the “infection of modernity”.

It was this revolution in design that Furner then carried into the partnership with Kennedy and Kallenbach from the end of 1928. Our brass plate gives us the three names but there were others in this large practice in the thirties. The support staff and effectively an apprenticeship system enabled young graduates or students gaining experience prior to completing their degrees to come into the firm and quickly solve practical problems of construction. A placement or a first job with Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner were 'much sought after and the practice became a center of modern design and a nursery for talent' to again quote Chipkin. Bernard Cooke, Rex Martienssen, Wilhelm Pabst and Bernard Clinch were all juniors working for KK&F in their early careers. Rusty Bernstein also worked for the firm. Over time a whole number of eminent architects came out of this office.

Patidar Mansions by Wilhelm Pabst (The Heritage Portal)

Notice too that the brass plaque includes the letters, ARIBA. These initials stood for Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Furner brought this prestigious British architectural status and recognition to the practice in 1920. He achieved the more senior accolade of FRIBA (Fellow of the Institute) in 1938. Those initials ARIBA, with the endorsement of British stature and status was not simply about snob appeal but made good business sense. ARIBA was about professional recognition, and a guarantee of quality work within a British educational framework that was adopted by the fledgling South African educational establishment.

The partnership succeeded as a practice of some distinction. Kallenbach proved himself for a second time as a successful professional and businessman, a property and township developer of Johannesburg. He is remembered today in the street name Kallenbach Drive. Kallenbach bought a swathe of farmland in Linksfield and together with Alexander Kennedy developed the suburb of Linksfield Ridge. Kallenbach built his own home on Linksfield Ridge and created what we today known as Kallenbach Drive and Kallenbach Pass. He and Kennedy donated the land that then made it possible for the city of Johannesburg to engineer Sylvia Pass.

Walking up Kallenbach Drive (The Heritage Portal)

Old photo of Sylvia Pass

Hermann Kallenbach passed away in March 1945 and in 1946 the name of the firm changed to Kennedy, Furner, Irvine- Smith and Joubert. From that date the familiar name of Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner ceased to be listed in the Durban directory. In the early 1950s, Kennedy designed and built his own home Steepways, on Linksfield Ridge. He died in 1967. Furner died in 1971.

It is serendipitous to discover the brass plate of the firm from Durban and that we at Johannesburg Heritage should be the lucky recipients of this memento. This name plate on a door, opens a window for us to explore an extraordinary personal story of Hermann Kallenbach and his architectural associations.

In conclusion there are a number of errors on the Artefacts web pages on Kallenbach, for example, Kallenbach did not build Munro Drive nor did he build Sylvia pass.

The story of his association with Mahatma Gandhi has been told from many angles. The missing narrative has been Kallenbach as a Johannesburg and South African architect.

This is a developing story. Kathy Munro and Shimon Lev are working on a fuller study of the life, times and achievements of Herman Kallenbach. We welcome photographs, personal family stories and connections to Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner. Email - kathy@zimstone.co.za

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand and chair of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.

Shimon Lev is an independent researcher focusing on Indian and Jewish studies. He received his PhD from the Hebrew University, Jerusalem (2016). His publications include Vesheyodea Lishol (Xhargol, 1998); Soulmates: The Story of Mahatma Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach (Orient Blackswan, 2012); From Lithuania to Santiniketan: Schlomith Flaum & Rabindranath Tagore (Lithuanian Embassy in New Delhi, 2018); and “Clear are the Paths of India:” The Cultural and Political Encounter Between Indians and Jews in the Context of their Respective National Movements (Gamma, 2018). He edited the Hebrew edition of Gandhi’s: Satyagraha in South Africa (Babel, 2014) and Hind Swaraj (Adam Olam, 2016). Lev’s art has appeared as part of many solo and group exhibitions and he has also frequently acted as curator, most recently for “The Mount: Viewing Temple Mount-Haram al-Sharif, 1839-2019” at the Tower of David Museum, Jerusalem (2019-2020). He is currently working on a book entitled Gandhi and the Jews – The Jews and Gandhi.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.