Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In today’s world, large infrastructure projects such as the state of the art “Gautrain” rapid transit railway between Johannesburg and Pretoria (80 km in length) are constructed using mechanised plant and equipment for better productivity when working to tight project schedules (fast tracking). Occupational Health and Safety on construction sites has become a main concern when it comes to planning and executing large civil engineering projects with hazard operability studies (HAZOPS) and risk assessments being mandatory. A Safety Officer is now an important member of the project management team and is responsible for safety awareness and ensuring that safety procedures are adhered to, for the welfare of construction workers.

Gautrain at OR Tambo Airport (The Heritage Portal)

Health and Safety was not always a priority and going back in time to the Industrial Revolution (1740 to 1860) the lot of a manual worker was fraught with danger and his life was often cut short by the hazardous work he undertook. His physical and mental wellbeing was of little importance to those men of inventive genius who transfomed human existence from a pastoral way of life to that of an industrial one.

Britain is where the Industrial Revolution began. It was more of an evolution over many decades as there was no “Eureka” moment and the technology that developed was based on the use of iron and the harnessing of the power of steam.

Necessity, as the saying goes, is the Mother of Invention and it was in the mining areas of Britain that the need was first felt to improve methods of mining and, once the minerals were mined, to find better methods to transport them to market. It was no accident that the North of England was where the ideas were distilled into practical solutions. Most of the richest coalfields of Durham and Northumberland were well inland comparatively far from the sea and the staiths (shipping points) on the navigable stretches of the rivers Tyne, Wear and Tees. It was hence with difficulty that coal could be got to market and until that was possible the coalfields were practically valueless.

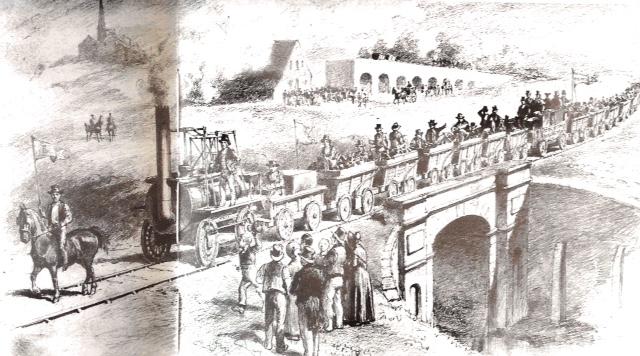

The conundrum to be solved was how to transport heavy loads at a cheap rate? The answer found was to build a railway and that is where George Stephenson (1781- 1848) came into the picture. Contrary to popular opinion he did not invent the first steam locomotive to run on rails (that was Richard Trevithick) and railways had been used at collieries since the 1780’s. Stephenson’s claim to fame was that he saw the potential of the steam engine (iron horse) as a prime mover of bulk materials and he had the persistence and fortitude to put his belief into practice. The outcome was the Stockton to Darlington Railway (S & D), which was the first steam operated public railway in the world. Public is the key word here as the S & D foresaw its role not only as a carrier of coal but also other goods and merchandise for anyone prepared to pay the haulage rates; this even extended to the carrying of passengers. The S & D opened on the 27th September 1825 and was soon to be followed by the world’s first intercity railway, the Liverpool to Manchester (30 miles), opened on the 15th September 1830, which is rightly recognised as a landmark in technical and economic development. Thereafter there came a clamour for other lines to be built which would become known as the “Railway Mania”.

First train on the Stockton to Darlington Railway (The Official British Rail Book of Trains for Young People by Michael Bowler)

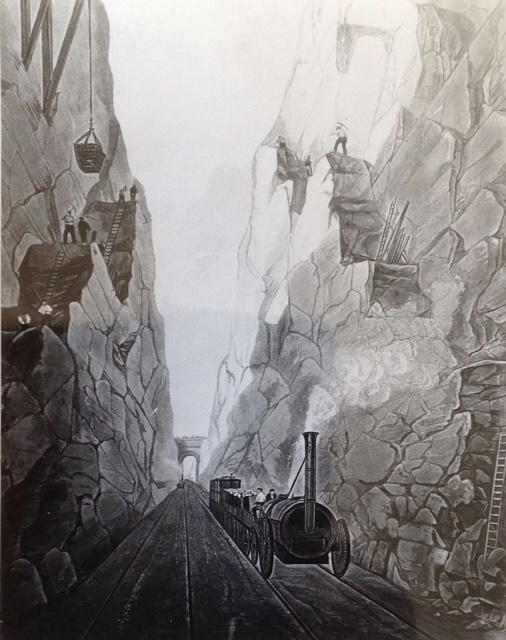

Olive Mount Cutting - Liverpool and Manchester Railway (British Railways LM Region 1964)

Opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (British Railways LM Region 1964)

The great Victorian engineers, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Joseph Locke and George and Robert Stephenson (father and son), are revered for their contributions to railway building in Britain during the period between 1820 and 1859, but their achievements could never have come to fruition without the arduous work done by the manual labourer better known as the “Navvy”.

The Navvy’s way of life has been encapsulated in the eight part TV mini-series entitled “Jericho” on ITV Choice where a band of Navvies and their womenfolk live in a shanty town in the shadow of a railway viaduct under construction (which is based on the Ribblehead Viaduct over Batty Moss on the Midland Railway’s Settle-Carlisle line).

The early railway companies appointed “The Engineer”, whose responsibility it was to plan and survey the route of the railway line, who in turn needed to employ subordinate engineers to assist him in preparing specifications, drawings and supervising of contractors; those men who had tendered to do a certain section of the line and thus constructed the permanent way (the prepared track on which the trains would run). Railways at that time, like the canals that preceded them were required to be level or nearly so, thus they needed embankments, cuttings and sometimes tunnels, plus bridges that spanned across rivers and multi-span viaducts that crossed wide valleys. Had the railways of the 19th century been built with today’s technology, that is to say with electric traction instead of steam power, then the railways could have more easily followed the undulations of the land; as they do with the new TGV lines in France.

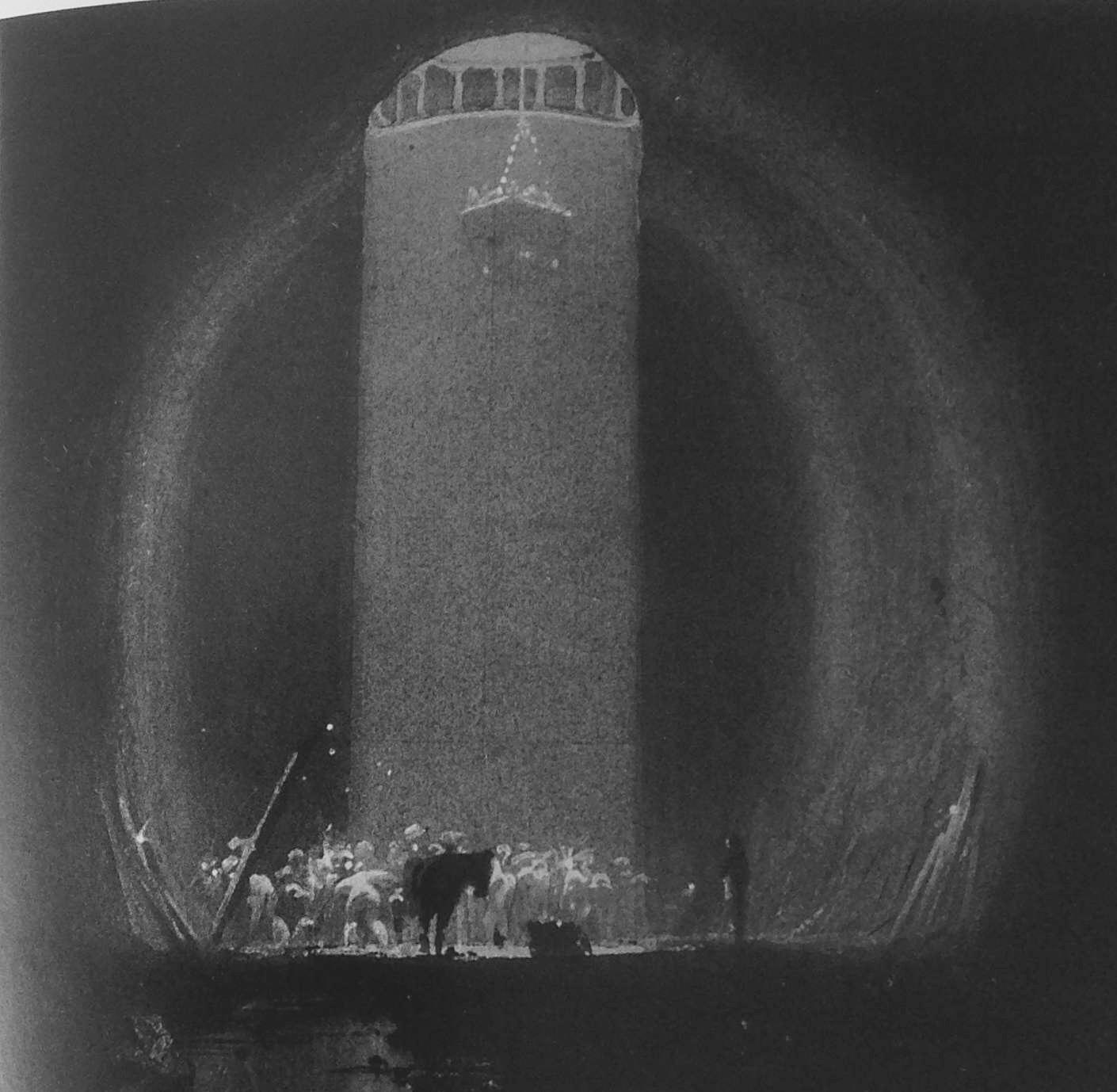

J C Bourne's depiction of a working shaft on the Kilsby Tunnel - 8th July 1837 (Men of Iron by Sally Dugan)

The foremost contractors in Britain and on the Continent were Thomas Brassey and S. Morton Peto and to these men came the task to find the wherewithal to undertake the work at hand. What this entailed was to employ an army of Navvies, under the corporalship of gangers, to do the digging, lifting and shifting which was done with basic hand tools: the pick, the shovel, the wheelbarrow, the lever (crowbar) and the pulley. The folksong “Poor Paddy Working on the Railway” expresses the pain and suffering experienced by an Irish Navvy who had come to England to escape the Potato Famine and is best sung by Luke Kelly of the Dubliners (click hear to view), the first verse and chorus are as follows:

"In eighteen hundred and forty-one - The corduroy breeches I put on - Me corduroy breeches I put on - To work upon the railway, the railway - I’m weary of the railway - Poor Paddy works on the railway."

Chorus: “I was wearing corduroy breeches - Digging ditches, pulling switches - Dodging pitches, as I was - Working on the railway”.

"In eighteen hundred and forty-two……”

The name “Navvy” was a corruption of the word Navigator, which had been assigned to a man who had worked with others in “cutting” the inland navigation canals of 18th century Britain; some 70 years before the coming of the railways. The Navvies were the unsung heroes of the 19th century railway building era and their prodigious feats of work and endurance became legendary. We who live today have no inkling of the physicality needed to perform work during the 19th century, whether it was as a farm hand, as a miner at the coal face or as a Navvy building a railway. Nowadays there are so many labour-saving devices that to stay in shape one has to head to the gym.

To say that railway Navvies had hard, sometimes short lives would be an understatement. They lived for the moment as their occupation was hazardous especially for those working in the tunnels, with the first Woodhead tunnel (3 miles long) under the Pennines being the most notorious. They had a reputation that preceded them and they were frowned upon by polite society. As they worked hard so did they play hard and were known to go on drinking binges which could last for several days (until their last farthing was spent) - the so called “Randy”. Their riotous behaviour was most feared by the local inhabitants that lived close to the railway workings and it was not uncommon for extra policemen, and sometimes the army, to be summoned in order to keep the peace. In spite of their hard living and their rapacious appetite for hard drink their achievements when sober changed the way in which people lived. They provided the means of rapid transportation by laying down a rail network which by the end of the 19th century interconnected every town and city in Britain.

By the late 1850’s the first railway boom was fast running out of steam as most of the rail trunk routes in Britain and Europe had been laid down and as a result the British railway industry had to cast its eye further a field in search of new projects. The colonies were ripe for development and with financial assistance from the City of London a second boom was initiated.

South Africa, or more particularly the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope (The Cape), was considered to be a possible and profitable market for the British railway engineering industry. However, it must be remembered that Britain was already a developed society with towns and cities well established (many since Roman times) and when it came to building railways it was simply a matter of joining the dots, whereas “The Cape” was largely undeveloped with only a few towns with most of its inhabitants living pastoral lives. The need for a railway was therefore not immediately evident. The idea was first raised in Cape Town as early as 1845, but it fell on stony ground and did not bear fruit. That was until the Cape Town Railway and Docks Company (C.T. R & D Co.) was formed in London in 1853 but even then there was more talk than action and only a proposal for a route between Cape Town and Wellington (gateway to the interior) was made. It was 1857 before a rough survey was made by a third party and it was not until April 1858 that a detailed survey was completed on behalf of the C.T. R & D Co. by their Engineer, William G Brounger, which would become the “Scope of Work” and the basis for the tendering procedure.

Brounger had been sent over from London, at the behest of Charles Fox (the renowned Consulting Engineer), arriving on 31st October 1857 (aged 37) and he would have a major influence on railway matters in the Cape Colony in the years to come (he can be well regarded as the father of railways in South Africa). He quickly realised that there was a paucity of engineering skills at “The Cape” barring a handful of ship’s engineers and a few mechanics operating stationary steam engines, therefore he was obliged to train (pardon the pun) his assistants. As for labourers versed in railway construction none were to be readily found locally and thus 300 Navvies were brought in from England. A recruitment drive had attracted men that had recently returned from the Crimean War, where they had served with the British Army (building a military railway), however not all the men that sought work were suited for manual labour and were in fact opportunists looking for a new start in the Cape Colony.

Interestingly the track gauge chosen for the line was 4 feet 8 ½ inches (1 435mm), which followed British practice, but in time this would not be used to extend the railway into the hinterland and in future it would be the narrower gauge of 3 feet 6 inches (1 067mm).

The contract for the line to Wellington was awarded on Christmas Eve 1858 to E. Pickering on condition that work would start within six months and that completion would be by 5th April 1861. As it transpired the railway would be opened in sections with through running between Cape Town and Wellington eventually taking place by 4th November 1863 – 2½ years late! The reason for the delay in completion was because of contractual disputes, which at times turned violent involving Navvies working on behalf of the contractor and those employed by the C.T. R & D Co. (ref. 10 gives a more detailed account).

On completion of the Cape Town to Wellington Railway (C.T. & W) there was no undertaking to extend it further and Brounger left his post to return to England; thus ended the first phase of railway building in South Africa. He would however be recalled in 1871 when the extension of the line from Wellington to Worcester was being proposed by the C.T & W. as the first stage of a railway linking Cape Town with Kimberley.

The Cape Parliament (on getting responsible government) had decided that railway matters were not to be left in the hands of private enterprise and consequently in 1872 they took over the C.T. & W and formed the Cape Government Railways (CGR), Brounger becoming its Chief Engineer. Conversely Westminster had chosen the opposite view and insisted that railways in Britain be privately owned and operated (so as to stimulate competition).

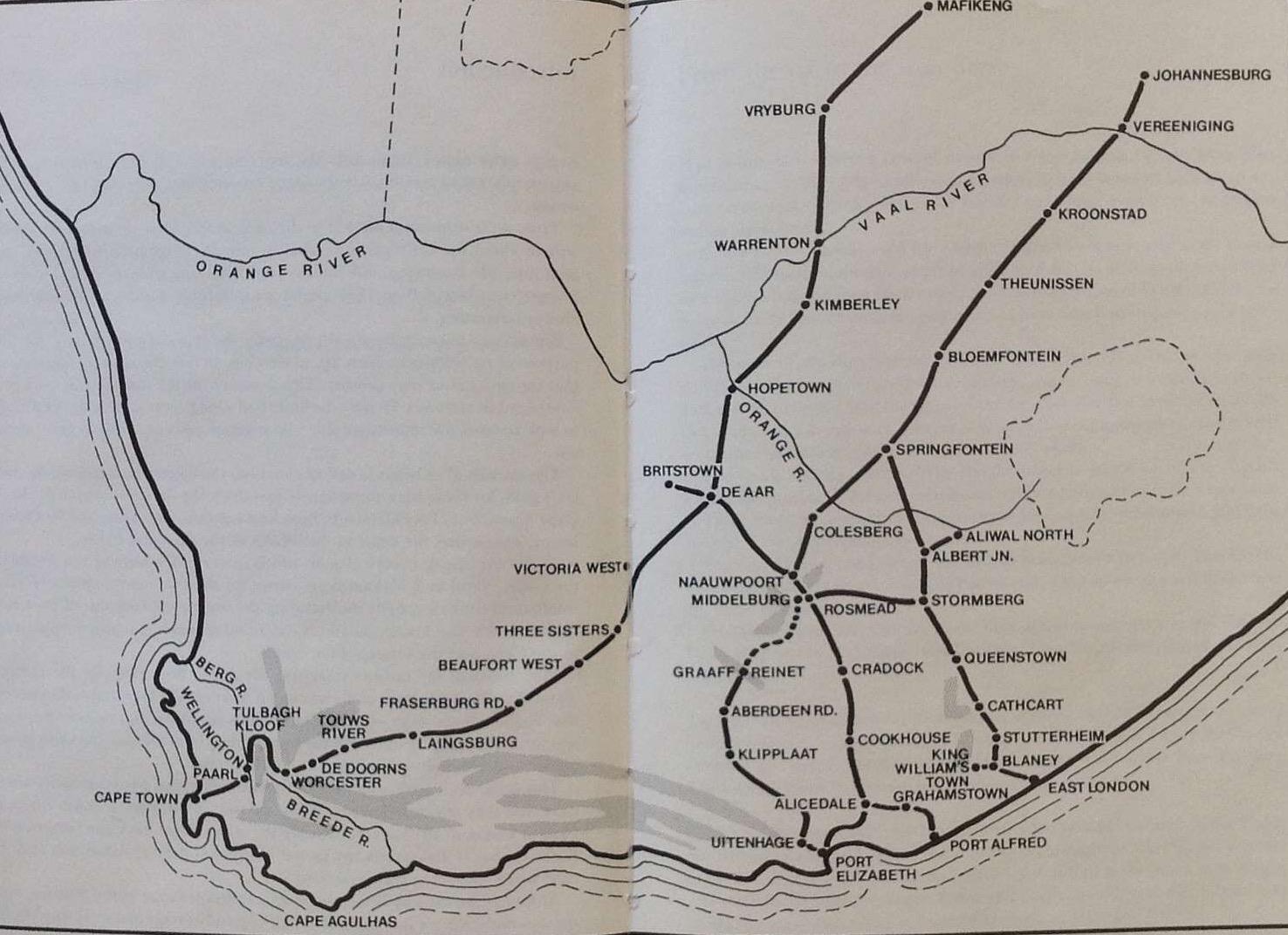

The discovery of diamonds in the vicinity of the Orange River (close to Hopetown), started a rush of prospectors to the region which culminated with the establishment of Kimberley (formerly called New Rush) which would become the second most populous town after Cape Town. Its importance to the Cape economy called for a three pronged plan for railway development whereby railway lines were to be laid down from the ports of Cape Town (CT), Port Elizabeth (PE) and East London (EL) with the diamond fields of Kimberley their goal (click here for a more detailed account - “Cape Gauge – From Ox-wagon to Iron Horse). The three proposed lines were nominated as being the Western (from CT), Midland (from PE) and Eastern (from EL). Only the Western line was in fact financially viable as it would run through settled areas linking old established towns together. The Midland line was not financially viable but political pressure was brought to bear by representatives of the Eastern Cape for a fair share of the trade with Kimberley. The Eastern line was the least viable on economic grounds but it was to be built as East London was the port nearest to the Border (with the Xhosa) and therefore had military value.

A railways department was formed under Brounger and he immediately recruited skilled staff from the ranks of young engineers in England. He also encouraged artisans and navvies to immigrate, however, the extent of the work could not be done economically without the recruitment of African labour.

Brounger would retire, due to a breakdown in his health, in 1884 (aged 64) and return to England having steered the CGR to reach the meeting point of the Western and Midland lines (on 31st March 1884), at a place in the middle of the Karoo called De Aar (“the Vein” in English), which was blessed with subterranean water courses much needed to replenish the boilers of the steam engines. The farm De Aar (which became a town), stood 72 miles (116 km) south of the Orange River and was for a short while renamed Brounger Junction, but the locals were none to happy with the name and it quickly reverted back to De Aar. It would become the Crewe of South Africa and its fame as a railway centre was to be much bigger than its actual size. The stretch of line onward to the south bank of the Orange River (close to Hopetown) would be officially opened on the 3rd November 1884.

Main Lines of the Cape Government Railways circa 1895 (Early Railways at the Cape)

With Kimberley almost in sight the CGR hit a snag as there was no money left to complete the works. The Cape Government had to go cap in hand to the British treasury to get an advance of £400 000 to complete the final stretch of railway (including the bridge) from the Orange River to Kimberley, a distance of 75 miles (120 km). The loan was agreed upon in March 1885 with the proviso that the line had to be completed within 8 months and it was to the credit of the contractor George Pauling and his gangs of Navvies that the feat was achieved. The first train steamed into Kimberley on the 28th November 1885, to great celebration as the whole town came out to greet its arrival. Although George Pauling lost money on the contract, he gained a reputation for his railway contracting and was able to recoup his loss in the course of a long and prosperous career.

First Cape train arriving in Kimberley - Drawing by Heinrich Egersdorfer (Cape Archives)

The establishment of a railhead at Kimberley, 625 miles (1000 km) from Cape Town marked the ending of the second phase of railway construction in South Africa. At the end of 1885 the only places going northward were the small towns of the 'bucolic, backward and bankrupt' Boer Republics (Orange Free State and Transvaal) and it made no economic sense to advance the line any further; the buffer stops were to be at Kimberley, finished and klaar.

No, not klaar as a mere six months into 1886 news broke of the discovery of gold in the outcrops of the Witwatersrand (The Rand), which would start the biggest gold rush that the world has ever seen and The Rand would completely eclipse Kimberley as the driving force of the region’s economy. The only rub was that the bonanza was not in the Cape Colony but instead in the Transvaal – a Boer Republic, only recently given its independence (for the second time) from Britain, although Britain still claimed suzerainty (overlordship). The boom town which sprung up beside the diggings would be called Johannesburg and the geological verification of vast reserves of gold bearing ore going deep into the earth’s crust confirmed that it was no “flash in the pan”. This knowledge would energise the third phase of railway building (click here to read “Race for the Rand“) and it immediately made the existing railways in the Cape Colony and Natal profitable.

Old mine workings at George Harrison Park. This is where the great discovery was made. (The Heritage Portal)

The fact that African Navvies, who did the heavy work in building our railway infrastructure, have hardly been mentioned in the references that I have quoted (see Nos. 10 to 17 below, 15 excepted), emphasises the lack of recognition for the important work they carried out in arduous and sometimes brutal conditions. Of the Beira Railway (covering 222 miles from Beira to Umtali) it was said that one person died of fever for every sleeper (cross-tie) laid down.

The only consolation is that we now live at a time in this country where there is more consideration for our fellow man than in previous generations and although what was done in the past cannot be altered, the Navvy of yesteryear should be held in high esteem for what he did, rather like the “Unknown Soldier”. Maybe it is time that a memorial statue was built in his honour? In my view Kimberley Station is where it should be placed.

Statue dedicated to the Navvies at Gerrards Cross (Wikipedia)

References and further reading:

- “The Industrial Revolutionaries – the Making of the Modern World, 1776-1914” by Gavin Weightman.

- “The Railway Navvies” by Terry Coleman (Penguin).

- “The Railways of Britain – A Journey Through History” by Jack Simmons.

- “A Social History of England” by Asa Briggs.

- “Men Of Iron: Brunel, Stephenson and the inventions that shaped the modern world” by Sally Dugan.

- “Salute to the British Navvy – a Memorial to Muscle” by Mary Nichols (This England – Autumn 1982).

- “Fred Dibnah’s Age of Steam” by Fred Dibnah and David Hall. The companion book to the BBC’s television series of the same name.

- “The Story of the Train” magazine published by the National Railway Museum, York.

- “Jericho” a period drama series on ITV Choice (2016).

- “Early railways at the Cape” by Jose Burman.

- “Girders on the Veld - Structural Steel and its story In South Africa” by Eric Rosenthal.

- “The Cape Government Railways” by W.G. Brounger M.I.C.E. (ICE paper No. 2049).

- “Who was Mr. Brounger?” by Roger S. Fairfax, “Railways” magazine April 1979.

- “Chronicles of a Contractor” by George Pauling.

- “Growth (and Segregation) by Rail: How the Railways Shaped Colonial South Africa” by Johan Fourie and Alfontso Herranz-Loncan, ERSA working paper 538, August 2015

- “Cape Gauge – From Ox-wagon to Iron Horse” by Peter Ball, Heritage Portal.

- “Race to the Rand” by Peter Ball, Heritage Portal.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.