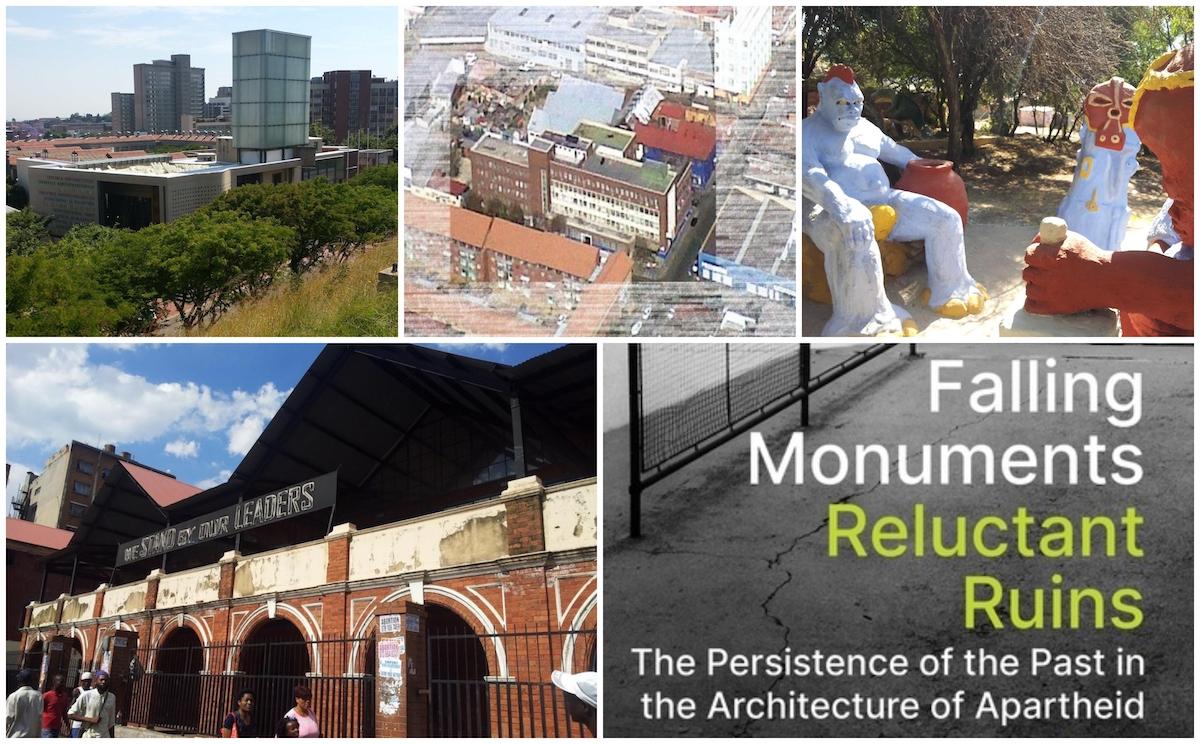

This is a collection of papers presented at a 2018 colloquium convened by the well-established Wits History Workshop, the Wits School of Architecture and Planning and the Goethe Institute. Conferences always produce an eclectic and distinctive mix of ideas and discussions. It is a platform to showcase research and produce a paper which will in turn bring further funding for ongoing research. Hence a wide range of heritage themes and buildings are explored by 14 contributors.

Book Cover

The sponsors have no editorial control so there was total freedom of expression for scholars to research, gather, talk and then to write up their work. A book of this type, heavy with the references, expansive bibliographies and archival sources itself becomes a valuable tool for other researchers. Click here for full details of the book.

I returned to the conference programme and noticed that some of the presentations (about 6) did not make it into the book. I would have liked to have read what Alan Mabin (always a critical thinker) had to say about the Union Buildings. I found it surprising that no one presented on the Rhodes Must Fall movement and what happens when statues are sent to a graveyard museum. So there are some gaps.

Watercolour of the Union Buildings by Herbert Baker circa 1910

The editor, Hilton Judin of the School of Architecture at Wits, gives cohesion to these diverse research papers. He has organized the book around three big themes of Land, Buildings and Statues. For Judin the central question is what is to be done with buildings, statues, objects and places - the infrastructure that survives from South Africa’s past. How can a post 1994 generation of scholars understand these past visible sites that belonged to the apartheid and colonial past? The hundreds of years of past history is given short shrift and truncated, it seems that all and every building and statue from the past carries too many traumatic memories to be preserved. That is a somewhat drastic view and leads to the conclusion that all colonial and apartheid public spaces and buildings should be expunged and demolished. The problem is that South Africa with its 11 official languages and multiple communities has multiple pasts. Heritage and commemoration cannot simply narrowly memorialize the top dogs of politics or concentrate only on the recent past. The demolition of past monuments comes close to a drive to at worse eradicate the past and at best to distort the past.

Muchapara Musemwa, an environmental historian at Wits and someone who grew up in post-liberation Zimbabwe, writes a juicy essay in the foreword. He tackles the dilemmas of his home country in the making and breaking not only of colonial sites of memorialisation such as the Rhodes grave on the Matopas but also what happens when a dictatorial ruler such as Mugabe is toppled and then turns his back while still alive on the National Heroes Acre monument and rejects it as a place for burial. Current political fights then determine the heroes to be remembered after death but revenge comes when the ex-saviour of his people, Mugabe snubs the resting place for heroes. Some lessons here for South Africa.

Rhodes Grave in the Matopas (Railways of Southern Africa Magazine)

I certainly had similar reflections when queueing on Red Square to see the famously embalmed Lenin close up; and for me the spectacle was a Madame Tussaud’s macabre experience but also a moment to think about who is and who is not a hero and how quickly time and events topple the heroes of the moment. In Vietnam the marble tomb of Ho Chi Minh is a giant mausoleum on a central square in Ho Chi Minh city under the watchful guard of army sentries. The man in the street can only stand in awe and feel totally insignificant when double or treble life size political figures are set on a mountain top imposed on the topography. The scale is all wrong. It worries me that we learn so little from our own and other people’s history.

Many of the essays in this book are the result of specialist and on going academic research. Faeeza Ballim contributes to the history of the Waterberg examining what happens when industry and mining disturb graves and burial places and local people suffer dispossession when an all powerful state wishes to build a power station. The bigger question is if an industrial project is not located here where should it be sited?

Eric Itzkin writes movingly about a community in Roodepoort being forced to leave their dead behind in a neglected cemetery and location homes are destroyed. Cemeteries tell about history and this is an uplifting account of restitution and recovery at Juliwe.

Aerial photograph taken after the demolition of Juliwe Township

Temba Middelmann describes and compares the transformation and remaking of Constitution Hill and Gandhi Square. Constitution Hill has become a museum, an exhibition space, the constitutional court, a public art gallery and a shrine of freedom that is now on the list of must see heritage sites in Johannesburg but it is also a place of memory. What is pubic space and what is private? Gandhi Square once Government Square where the court was situated, later became Van der Bijl square and bus terminus and since 1999 it is Gandhi Square and managed as a commercial space with the central focus on the young Gandhi as lawyer. It is also a space of heritage memorialization with a blue plaque marking the British occupation of Johannesburg in 1900. Middelmann draws out the ironies, conflicts and complexities of these spaces. He sees the promotion of Gandhi as a hero neglecting the African experience in the city.

Constitutional Court (The Heritage Portal)

The Blue Plaque on Gandhi Square (The Heritage Portal)

Authors Nare Mokgotho and Molemo Moiloa, writing under the collaborative project name of Madeyoulook, write about black gardens as art installations in a colonial museum, namely the Johannesburg Art Gallery located in Joubert Park. I was puzzled by this contribution as the authors appear not to have engaged with the Lutyens vision for the Johannesburg Art Gallery in the principal park of the day and how the work of Lutyens was strongly influenced by Gertrude Jekyll. It would be a gift to the densely inhabited residential area of the city if Joubert Park were restored as a garden. I like their ideas, they are clearly men of action.

Johannesburg Art Gallery (The Heritage Portal)

Sally Gaule writes about the Johannesburg Central Police station (the place that those of us who lived through the apartheid era know as John Vorster Square) from the perspective of the photographer. She reminds us that this was not just a police station but a building where political detainees were held, brutalised, intimidated and tortured. It bears comparison to Lubyanka, home of the KGB in Moscow. Sally’s view is that this building the epitome of apartheid has remained unchanged and with a past that continues to haunt us.

Kelly Gillespie raises questions about what happened when Robben Island closed as a prison and the prison warders were relocated to Voorberg Medium B prison in Porterville; this essay gives a glimpse into adaptation and change in the prison service but fails to grapple with the central heritage question of how to sustain Robben Island as a museum. Robben Island may be a world heritage site but with the dearth of tourists and neglect, its future as a museum is now in question.

Hilton Judin writes about the history and meaning of the Central Pass Office at 80 Albert Street, Johannesburg. The pass system worked as the cornerstone of enforcement of apartheid in the city. Black people needed a pass to live and remain in the City. It was a system of control and dehumanization as men could not remain in the city without work, but without a pass you could not seek employment. It is another building that exhibits the “banality of evil”. After 1994 the building became a Womens’ shelter. Judin raises the question of what to do with such a traumatic legacy of cruelty. Memory also has to include writing the history of the system and the place. James Ball wrote his Masters thesis on the Pass Office and an essay for the Heritage Portal.

The Albert Street Post Office from above (The Heritage Portal)

The Dadoo family business at Jubilee House in Krugersdorp is explored in a well researched essay by Arianna Lissoni and Roshan Dadoo on how the successful Indian Dadoo family built their trading business and commissioned the architectural firm of Kallenbach, Kennedy and Furner to design an impressive Art Deco, modernist building in the late 1930s. This contribution combines social and architectural history and places it in the context of political activism and changing demographics. This is one of my favourite essays, and the authors are on the inside track with access to the family archives. However, I sought in vain for a connection to heritage preservation or the theme of falling monuments. The case study of a family business shows that there are other dynamics at work.

The Johannesburg Drill Hall is a heritage site with a long history going back to 1904, when the Union Grounds was a military parade. The Drill Hall‘s history, summarised here by Barbara Morovich and Pauline Guinard, is indeed a palimpsest of a convulsive past when the Treason trial of 156 activists commenced here in 1958. It ceased to be a military centre in 1992 but by the early 2000s was given a reconciliation makeover with a R10 million renovation overseen by architect Michael Hart. I recall a now very collectable celebratory booklet produced at the time. However, despite the reinvigoration, it is a failed heritage project, an important place in the city which ought to be administered by the City of Johannesburg but is owned by the Public Works Department. Despite an appeal by the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation to the Minister of Public Works to effect a legal transfer to the City of Johannesburg, ownership still hangs in the balance. In this instance decay and ultimate disappearance of an important heritage site will happen by neglect, natural decay and misuse. It highlights that for a heritage property to have meaning there has to be an agreed upon future purpose that makes economic and legal sense.

The Drill Hall (The Heritage Portal)

Yasmin Mayat and Brendan Hart happily combine a heritage architecture practice with a commitment to academic work and were the architects of the reconfiguration and reimagining of the SS Mendi Memorial at the Avalon Cemetery in Soweto. They were also part of the team that undertook the addition of a new layer of heritage at Delville Wood in France. The history of the battle of Delville Wood has been covered in detail by military historians such as Peter Digby and Ian Uys, so this essay is a recap to explain the context for the addition of a new memorial pathway with side stone panels incised with the names of all South African participants who lost their lives in France at the Baker designed 1920s Delville Wood memorial. It is a memorial that captured the soul of South African identity but through political changes that identity was rethought. I have visited the new memorial in France. It is restrained and does not jar. The one negative is that within a year of installation the names on the Portland stone panels, are being covered with moss. I found comfort too though in finding the name of my great uncle who fought and survived the battle of Delville Wood only to be lost at the age of 19 three months later in another engagement, the Butte de Warlencourt on the Somme. His body was never found and he became one of the thousands of “ missing”. Both these memorials in France and Soweto lead to reflections on futile loss of the lives of young men in war and how old memorials can be made more inclusive.

SS Mendi Memorial Service 2019 (City of Johannesburg)

Credo Mutwa’s cultural village in Soweto is a strange place as here a black artist, author, storyteller, architect, medicine man created a history and a village of his making encouraged during the apartheid era by the West Rand Administration Board. The story of this, some would say invented heritage, is explored by Ali Hlongwane and Tara Weber. Considering the context, history and controversy they handle their subject with sympathy and draw the parallel to Helen Martins' Owl House near Graaff-Reinet in the Karoo. Considering the ideological position of Mutwa is central to analysis. It is a difficult legacy to interpret as authentic heritage as Mutwa only passed away in 2020. I have visited the Mutwa village and watched a marriage ceremony presided over by Mutwa. It seemed to be he was very much out of the main stream and could only be understood as a mystic.

A scene from the Credo Mutwa Cultural Village (The Heritage Portal)

Cynthia Kros questions whether the Nelson Mandela statue on the balcony of the Cape Town City Hall faces down the coloniser as he gazes over the Grand Parade. How does this statue stand in relation to that of Edward VII on the Grand Parade? Who faces who down! Cape Town City government in the hands of the DA party commissioned a bronze life size statue of Mandela. It was unveiled in 2018 so is a recent “heritage“ addition and illustrates that whilst history is about the past and can be interpreted in many ways, heritage is a living current expression of a changing city politics. Kros covers the history of the political decisions behind the statue well. The statue and accompanying exhibition came in in the region of R5 million and was the work of two bronze scluptors Barry Jackson and Xhanti Mpakama. It is another new addition to the tourist route in Cape Town.

Goolam Vahed contributes a chapter on a proposed monument to Indian indentured labourers in KwaZulu Natal. 2010 was the 150th anniversary of the arrival of these labourers who came to work on the sugar plantations of Natal. It was proposed to erect a monument to these labourers and their struggle. Vahed is at pains to explain the international relevance of recognition with a monument by their descendants. A foundation was established to start the campaign and in 2010 the then premier of KZN set aside R10 million for this planned monument. It seems that in 11 years there has been little progress and no monument. The Indian community feels excluded in the symbolic landscape of the making of heritage and monuments.

The essay was penned in 2018 but now in 2021 there is cause for even more of a sense of loss with the recent events of riots and insurrection in KZN and Gauteng but with Durban as the epicentre and Phoenix a hot spot. This is the afterword which reveals how much a conference held just three years ago with a book appearing this year is overtaken by immediate, horrifying events that push South Africa onto the edge and with the destruction of so many factories, shops, malls and business makes heritage commemoration seem quite irrelevant.

Well that is one view but perhaps there is another interpretation that Heritage and how we understand one another across races and class is even more imperative to address and to reach out in tolerance and inclusiveness if we are to find one another.

The final contribution is by Nnamdi Elleh and is a neat book end piece to the foreword by Musemwa. Elleh gives a welcome African and international perspective to monument making and commemoration. He calls for new languages in architecture and scholarship. Monuments are ideas and debates in progress. The challenge is to bridge the gap between past and present. He stretches the meaning of monuments - for example that memory keeping sites for traumatic events become de facto courts of justice and considers that in both Spain and Zimbabwe dictators were expelled from their country’s heroes’ resting places. Here is a reminder too of the minimalist monument movement in the USA expressed for example in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington.

This book is a useful addition to discussions about heritage and stimulates thought about who are the heroes today, how do we remember the immediate past and what do we do with the controversial memorials about the remoter past.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.