From Mining Camp to Metropolis the buildings of Johannesburg 1886-1940, Gerhard-Mark van der Waal, 1987, publisher Human Sciences Research Council and Chris van Rensburg publications, 268 pages, illustrated, with maps.

If I limit myself to three books on Johannesburg to explain the evolution of the city in an historical context, the choice is obvious. My three top books on historical Johannesburg have to be Gerhard-Mark van der Waal’s “From Mining Camp to Metropolis” (1987), Clive Chipkin's "Johannesburg Style" (1993) and Keith Beavon's “Johannesburg, the Making and Shaping of the City" (2004). Together these three histories give us both a focused narrow and also a wider social history to explain how and why Johannesburg evolved from mining camp to modern city. Van der Waal and Chipkin are architectural histories while the Beavon is an historical geography of the city. Chipkin wrote a second and even more impressive volume in his "Johannesburg Transition" (2008). I also rate this as an essential and a magnum opus. I shall write about these books and the Beavon book in later review columns.

Today, my brief is the van der Waal. I have long promised myself to pull out the volume from my Johannesburg collection and pay homage to his efforts, even though it is now nearly 30 years since the book was published. It is the book that has stood the test of time and is still the obvious choice, a "vade mecum" (literally a 'come with me' or guide me sort of book as you walk the streets), for anyone wanting to engage with Johannesburg architecture for the great period of growth and coming to maturity of central Johannesburg and the old suburbs, that is Johannesburg from 1886 to 1940. If you are writing about Johannesburg, one first turns to van der Waal to see what he says about specific buildings, places, people and spaces.

Book Cover

The book was very much an establishment project of the apartheid era and grew out of an initial Rand Afrikaans University study for the City of Johannesburg in the 1970s to systematically survey the architectural heritage of Johannesburg. Van der Waal moved from studying the character of the pre-1920 inner city architecture for a Masters thesis to undertaking a more comprehensive documentation of the city's architecture up to 1940. Extensive financial support was provided by mining houses and key industrial and property companies of the time to subsidize publication and indeed the book appeared to coincide with Johannesburg's centenary.

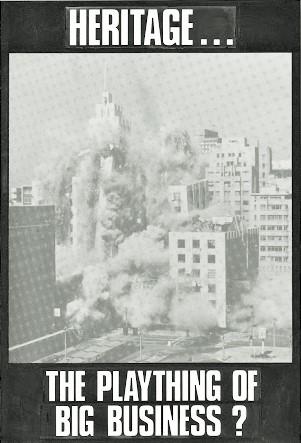

The study of Johannesburg's heritage buildings came at a time of grand planning in the city. The cataloguing of buildings of historical significance that ought to be preserved gave substance and support to the conservation lobby. In that sense van de Waal's work made an enormous contribution to heritage and to recognizing Johannesburg as a unique city with a sense of place and a heart. In the long run it is economics, financial buoyancy, profitability of property and the market that drives the decision to demolish and redevelop. Although the City of Johannesburg appointed an architect, as "aesthetics officer" to control the visual appearance of new buildings, what shaped Johannesburg in the latter 20th century were the longer term limitations of politics, new investment patterns, highway systems, and shifting demographics working either with or against the imposed planning regulations. Hence Johannesburg in the seventies when the study was published moved and stretched geographically north, south, east and west. The Sandton City development of the 1970s was a significant catalyst for moving wealth and ultimately the business heart of Johannesburg northwards (to Rosebank, Sandton, Randburg, Rivonia and on towards Midrand). Johannesburg morphed, appropriated, changed its shape and boundaries and became the mega city of today. Old Johannesburg, despite the wave of implosions including the old Escom House, the Newtown Cooling Towers, the Plaza and the Colosseum, was largely saved through the decisions of the capitalist property market to go elsewhere. The Banks collectively, Standard Bank, First National Bank (Barclays) and later ABSA remained in the old city to build their multi block “bank cities", but enough of the old apartment and office blocks remained to give Johannesburg that recognizable Art Deco visual look.

I think this abbreviated recap of longer term trends is important to enhance our appreciation of van de Waal. This book was not simply a narrative historical account but created a pioneering framework for preservation and heritage labelling.

Protest Poster from the early 1980s showing the demolition of Escom House (Franco Frescura)

Johannesburg was a city with its roots in the gold mining industry and its buildings reflected the progress and success of mining which was at the thriving heart of the city as it shifted from rough and ready mining camp, to tentative more permanent town, to the economic, industrial metropolis of Africa. Van de Waal has structured his book around four themes enveloped by periods: the mining camp, the Victorian mining town, the Edwardian industrial city and finally the modern Metropolis of the interwar period. This makes for unbalanced periods, 4 years, 10 years and two twenty year longish timespans. Nonetheless there is a skillful blend of surveying different types of buildings and contrasting inner city with the burgeoning new (now old) Johannesburg suburbs as the city marched beyond the original Randjeslaagte.

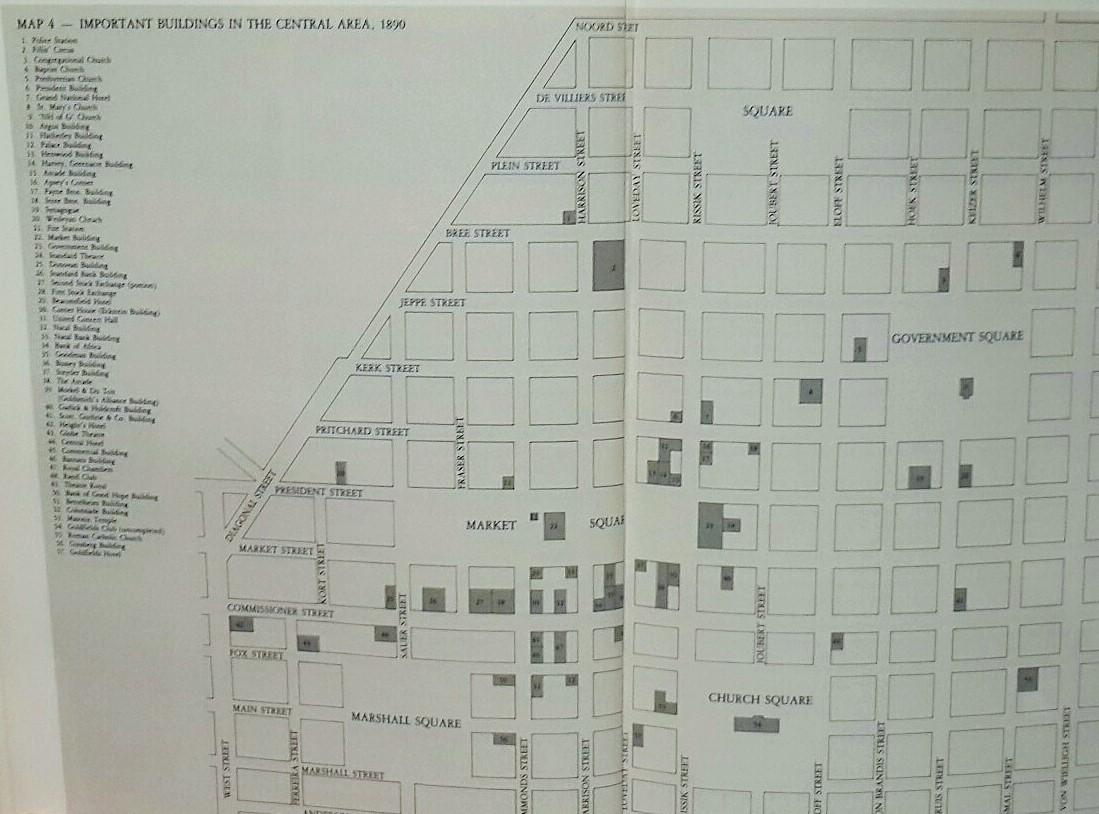

The inclusion of 8 maps is an excellent reference source and the effort to pinpoint where important buildings were located on the city grid is an invaluable reference source.

An example of the grid map showing the location of important buildings

It is not a book without omissions. The termination date for this study was 1940 (turn to Chipkin's two books for later decades). The relationship of Johannesburg to the Witwatersrand gold mining towns to the east and west was missed. Springs, Boksburg, Benoni, Brakpan, Germiston cry out for an urban history and architectural coverage. Then, what about Soweto, which erupted in 1976 onto the world stage as the point of resistance and Revolution? Here was a parallel apartheid and segregation created dormitory city. Van de Waal sets the scene for the shaping of the "modern metropolis" with some discussion of town planning priorities which included the new competition of the new suburb of Orlando in 1931. A final omission in my opinion is the absence of the economics of the city ... Where and how did money flow, how were buildings financed, what did a specific important building cost, how did the successful accumulation of capital translate into bricks and mortar?

Van de Waal's approach is to study the city through its buildings categorized according to purpose and type (government, institutional, theatres, clubs, schools, churches, offices). Particularly interesting sections for local historians are the histories of the suburbs of the city from the homes of Doornfontein of the early years, to the villa neighbourhoods of Belgravia, Hospital Hill and Parktown to the north east in the 1890s, and finally the diversity of suburban options of the 1920s and 1930s when the domestic architecture of suburbs such as Houghton and Melrose enabled successful individuals to choose an architect ready to experiment in the Modernist or International styles. Van de Waal has a fluent command of trends in architecture and the diversity of approaches used to express individual taste and pocket. Strangely though, the standardization of themes in each chapter and the emphasis on building types means that the role of the architect slips into second place. A good many architects are mentioned but the contribution of the architect, whether it's Baker, Leith or Kallenbach is not fore grounded. Van der Waal makes very few comparisons of Johannesburg to other colonial cities and in that sense it is a young scholar's book and betrays its origins as an academic thesis.

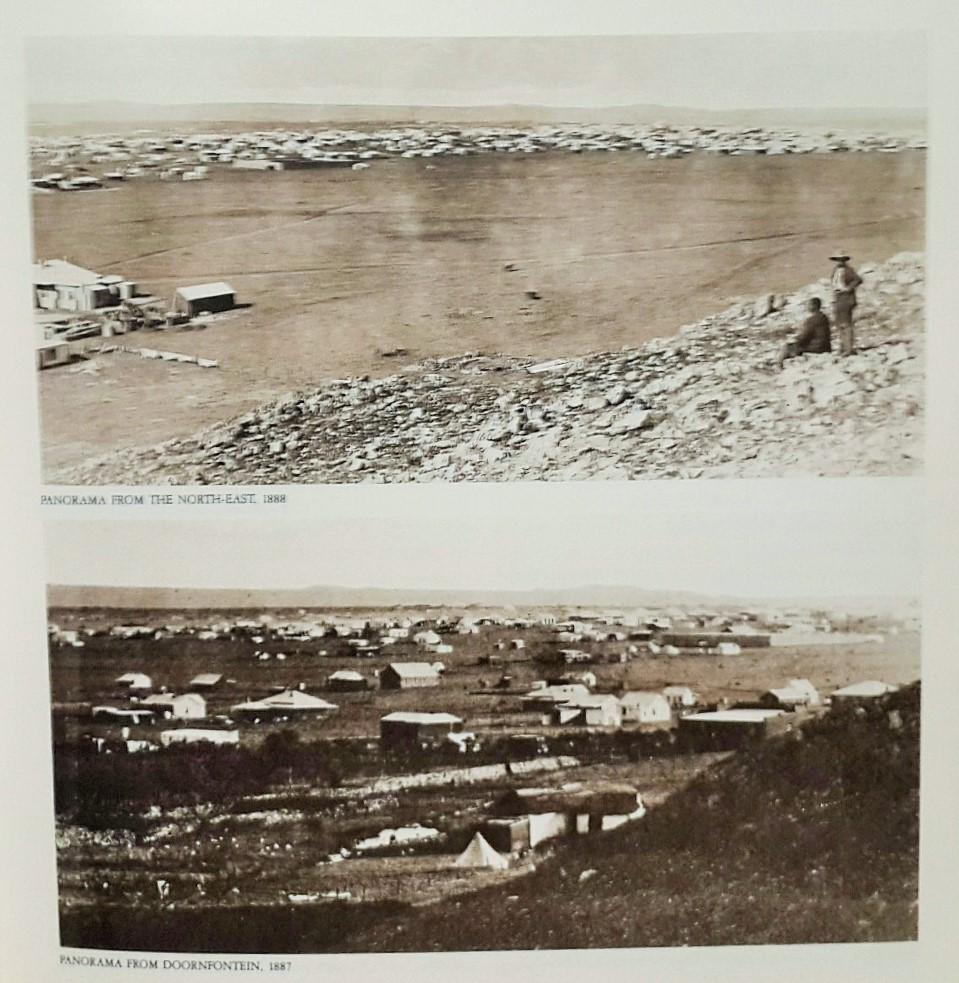

However, what van de Waal does brilliantly is to relate the building, and the facade to the street scape, and explains how buildings related to their setting. His objective was to place emphasis on the spatial and functional links between buildings and their environment. He explains how city planning and building regulations created the framework for the potential and possibilities and ultimately reality for the buildings of the city and its suburbs in his four selected periods. The author moves effortlessly from panoramic distant vistas of the city to streetscapes to close-up building facades.

A strength of the book is the many photographs sourced from contemporary books, albums and magazines as well as from Museum Africa (Africana Museum / JPL) collection. The large full and half page sepia toned illustrations work best, the small strip illustrations at the top of a page are too tiny to view without a magnifying glass and there are some blank spaces, which look odd. But here I am carping about layout and design, which was not the author's brief. While on design, the style of the book is very much in line with the particularities of the Chris Van Rensburg publishing house, that is it is designed for armchair or desk study, being a large 'coffee table' size, so it is not the sort of book one can use as a walking the streets guide which is what you need to match the text to the buildings that remain.

"A stength of the book is the many photographs"

The depth of scholarship of the book is shown in the detailed notes and references, the comprehensive bibliography of sources and a solid index.

Van der Waal is a much sought after book, but in many ways it is under appreciated perhaps because it has such a period look with the profusion of illustrations in sepia tones. The book was also published in Afrikaans. Fortunately for collectors of Johannesburgiana the books is still fairly readily available in antiquarian book shops or on line and the price comes in at anywhere between R500 (Bidorbuy site in Afrikaans) to $100 for an English title. I think it is a title that still has the potential to rise in price, and as more collectors become aware of this classic the price will indeed rise as the book is out of print. I stand to be corrected but my impression is that the book was written in Afrikaans and then translated into English and the two translators, Erasmus and van den Berg deserve an acknowledgement for a job well done.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories.