The launch of this massive study on the subject of Dutch architectural history, presence and influence in South Africa in the 20th century took place in October this year. It was the culmination of a keenly awaited team project. I was privileged to attend the function at the Netherlands Embassy in Pretoria. In the wake of Covid, technology has come into its own and the symposium was a multimedia event with participants online in Cape Town, Swellendam, Amsterdam and Pretoria. We could all see one another on screen, the conversations flowed and people glowed with quiet pride at the achievement. Each of the contributors (there are 15 authors) made a short presentation on the essence of their research contribution and it all added up to an interesting evening.

The publication is a high profile project with close cooperation and collaborative research over a few years by Pretoria University and Netherlands scholars.

The theme is the Dutch contributions to architecture in South Africa in the 20th century, with the period defined as post South African War (1902) to the declaration of the South African Republic (1961). The coverage is thus just sixty years. I would have preferred a century long overview to have more of a long time span. Nonetheless, this book packs in a vast amount of research and includes many rare photographs and plans over a six decade span.

I was puzzled by the choice of a termination date, 1961. I raised this question at the launch and then Roger Fisher wrote back a good explanation which is worth sharing:

While no year is clear in defining a change in architectural direction, the establishment of the Republic was, for the Afrikaner Nationalists, a return to the idyll of independent Boer Republics which connects us back to the Eclectic Wilhelmiens episode. The other significance is that all architectural production up until that year in 2021 becomes subject to the SAHRA Act hence all that we include is now significant in terms of our own Heritage legislation. We have also created SAHRIS entries for all the works discovered.

This is a magnificently produced book – and certainly an august and weighty publication – literally and figuratively. It weighs in at nearly two kilos. It has the look of a fine coffee table book but it is so much more than a show title. The lavish production means that each contribution is given due respect. Each chapter is beautifully illustrated. The fine photographs drawn from archival and current sources enhance this prestige publication making it a superb visual feast.

There is an impressive line-up of sponsors - the University of Pretoria (where the researchers are mainly based), the Embassy of the Netherland in South Africa (they hosted the launch), the South African Heritage Resources Agency, the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency, Zuid-Afrikahuis and Dutch Culture. With this level of support the book is extremely well priced at only R695 and available through Protea Books. I would say this is the best value for money book of the year!

The project is just one of many pioneered by the Kingdom of the Netherlands promoting past cultural influence of the country across the world.

This rich collaborative study is a sequel to Eclectic ZA Wilhelmiens: A Shared Dutch Built Heritage in South Africa (editors: Karel Bakker, Nicholas Clarke and Roger Fisher) published in 2014. The earlier volume was the first taste of serious scholarship coming out of the Department of Architecture at the University of Pretoria; that book despite the unwieldly title, with everyone wondering about the word 'Wilhelmiens') concentrated on the Dutch inspired and rooted architecture of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek. Wilhelmiens was derived from the name of Queen Wilhelmina who was the Dutch monarch from 1890 to 1948 and the title was meant to challenge the all too frequent and erroneous use of the term 'Victorian' architecture for the pre-Boer War Pretoria scene.

Eclectic ZA Wilhelmiens Book Cover

Common Ground builds on the success and track record of the earlier book but is even longer and ranges over all of South Africa. The central theme is looking for a shared Dutch – South African inheritance and association; there is a deliberate intention to steer the academic debate away from forms of colonialism and rather and with a serious study of roots and mutuality of ideas, styles and trends in architecture. The goal is to build a strategy to make the case for the preservation of worthy 20th century buildings. I wondered why the image of the Cape Town Newlands Swimming Pool and grandstand designed by Jaap Jongens in 1955 of all the possible choices should have been chosen for the cover image.

Newlands Swimming Pool (Francois Swanepoel)

A seafaring tradition enabled Dutch ideas and architecture as a successful and well appreciated export but there is little mention of the earlier Dutch impact on Southern Africa from the 16th to the 19th centuries. We are familiar with the earlier contributions of the Dutch to South African colonial architecture at the Cape and the local adaptations that followed. The Cape Dutch style of farmhouses is a picturesque and popular theme of many Cape books but there is nothing about those earlier architectural roots here.

Each chapter explores a different theme and is really an independent essay on a specialist subject and hence the richness and diversity of topics.

Common Ground Book Cover

A general introductory chapter (by Marieke Kuipers) sets the scene with an explanation of the starting point for this study – what does the concept of a 'shared heritage' of South African and the Netherlands mean? This is the big idea that underpins this book. The sharing of heritage makes it possible for scholars to move beyond the simplistic damning of 'the colonial' and all structures built during the apartheid period. Instead, the scholars suggest that we should be reassessing and documenting Dutch architecture on its own terms. How did these two cultures exchange creativity in architecture over 60 years? There is a huge stylistic diversity and Dutch architects working in South Africa were more important than has been realized or recognized up until now.

This study aims to broaden the knowledge of architecture in general with a particular focus on the Dutch contribution to that legacy and to give and share their research and insights with a far wider range of communities than would normally read architectural histories.

The second chapter explores why the Netherlands became a country of emigration at a time when Europe was beset by war, decolonization and economic crisis. Why did the Dutch feel a special affinity to South Africa and why did trained professionals in engineering, and architecture emigrate. Here is a useful overview of Dutch society and culture. Kuipers delves into the 'push' factors that prodded people to emigrate. Stunning photographs give a good feel for the modernization of the Netherlands in the fields of housing and industry after the Second World War, but for many renewal did not always bring the rewards they hoped for and emigration was an alternative.

.

There are four 'interlude' sections. These can be seen as stand-alone, bonus treats supported by even more amazing old photographs. I was not sure of the basis of the decision to assign a topic to an interlude or a main chapter but it hardly matters as it all adds to the rich tapestry of new knowledge.

The first of the interlude chapters is on Dutch architectural education by Kuipers and van der Wat. This will appeal to educational historians but how did Dutch education speak to or interact with South African educational approaches to architectural education? Could a Dutch trained architect simply set up a practice with his plate on the door when he arrived in South Africa? How did the newly arrived Dutch architect fit into a British-based educational system with recognition through the Royal Institute of British Architects? The coverage is about the Dutch approach to architectural training in the Netherlands and explains the links between vocational training, technical colleges and academies.

Annie Antonites explores the two waves of Dutch immigration to South Africa in the 20th century. Dutch immigrant numbers to South Africa between 1902 and 1955 amounted to an estimated 37 000 - it is a small cohort but made a big impact. She explores why South Africa was a desirable destination and gives an overview of the South African conditions noting that Dutch artisan immigrants were regarded as desirable because they were skilled and filled labour shortages.

The architects from continental Europe arrived with new cultural influences, different backgrounds to the locals and plenty of new intellectual stimuli could be sown on local soil to bear fruit quickly. More than seventy Dutch architects came to South Africa after peace returned in 1902 and in the decades that followed. Across the country there is a huge built legacy – bank buildings, recreational facilities, department stores, monuments, educational buildings, churches, industrial buildings, private homes, public service and community buildings.

The second interlude bonus chapter on Cross-Continental careers by Nicholas Clarke and Marieke Kuipers provides useful original sketches of the careers of Dutch architects who worked in both South Africa and the Netherlands. We learn about the careers and movements of Johan Coenraad Meischke, Johanna Eleanor Ferguson, Antonius Voorvelt, Jacob Cornelis Jongens, Henrik Theodoor Otto Niegeman and the last in this group, Chris Wegerif. These talented people were born between 1889 and 1905 and left some impressive churches, industrial blocks, office blocks and homes. I was particularly delighted to be introduced to the small World War I war memorial to be found in the Pretoria Station Gardens for the S A R and H, designed by Voorvelt. Fergusson was one of the first female architectural engineers in the Netherlands. This group is interesting because they throw light on the intercontinental transfer of expertise.

J C Meischke is a noted name in Johannesburg for his Meischke’s Building which once housed the Guildhall Bar and Frank Thorold’s bookshop - both city institutions (The Heritage Portal)

Nicholas Clarke writes about Civil Works and Community buildings. There are insights about how Dutch skilled engineers and construction companies won the contracts to contribute to the Herbert Baker Union Building project. Dutch talent was involved in the design and construction of town halls, fire stations, hospitals schools, libraries, stadiums and university buildings across the country. Water infrastructure is completely new and points to the blending of architecture and engineering. Here is a chapter with much original research that deepens our knowledge.

An early photo of the Union Buildings

Marieke Kuipers contributes an impressive study of serious commemorative monuments and celebratory frivolous festival buildings; its an impressive legacy that stretches from the Anglo Boer War Women’s Memorial in Bloemfontein (Frans Soff) to the Huguenot Monument at Franschoek (Jaap Jongens) to the transitory Culemborg Town Hall replica for the 1952 tri-centenary festivities, remembering the arrival of Jan Van Riebeeck. The Rand Easter Show at Milner Park had a Netherlands pavilion (the work of Jaap van Niftrik) and I certainly recall that as a child we were drawn to the displays of Dutch tulips and packets of Dutch black liquorice and the chance to buy a quaint pair of clogs.

Huguenot Monument Franschoek (The Heritage Portal)

Nicholas Clarke has contributed a fine chapter on churches or as he terms it, buildings for Communities of Faith, including Dutch Reformed churches (NG Kerke), Protestant churches and Catholic churches. Some examples in this chapter resonate with the new book by Menache and Roux (in Afrikaans) on the N G Kerke of South Africa. The Swellendam Dutch Reformed church designed by the father and son team, Folkert and Francois Hesse in 1911 features. It is a surprisingly beautiful building with an eclectic but strange mix of Cape Dutch, Baroque and Gothic architecture. For me learning more about this church brought back happy memories of listening to the organ recital in this building during the Swellendam Heritage symposium. Some magnificent churches are highlighted in this chapter.

The Swellendam Dutch Reformed Church (Wikipedia)

The Netherlands Bank of South Africa was founded in the 19th century in the Netherlands but its purpose was to bring Dutch banking to firstly Kruger’s Republic and after the War, to promote their banking business across the country. Catherine Deacon and Marguerite Pienaar explore the legacy of fine bank buildings erected by the bank in the main urban centres – Pretoria, Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth, Bloemfontein and Durban. Best known of the Netherlands Bank buildings was Norman Eaton’s 1960 Durban building. The second part of the chapter looks at Dutch related industries of architecture. This chapter is impressive for the rich photographic archive that has been assembled of buildings that are often passed over but are worth a look beyond the functional.

Netherlands Bank Building, Durban (Roger Fisher)

Arthur Barker has written about Pretoria homes and houses between 1902 and 1961. He presents his study of dwellings in the context of a localised regionalism. Many of these homes were both practical and picturesque; this chapter should not be overlooked as Barker draws attention to the popularity of art nouveau (jugenstil) style.

Another interlude is Esther de Haan's piece on kitchen design in 20th century houses. It is an unusual topic and women probably spent a lot of time in this 'heart of the home'; at a time when mothers were expected to occupy themselves with ‘Kinder, Küche, Kirche‘ (an old German expression – children, cooking and church) that applied in many societies where women were not expected to have careers. Kitchens in old houses were hopelessly old fashioned, often inefficient and assumed that the woman of the house either had half a dozen servants to manage the kitchen or was herself both queen and maid of the kitchen. Over time, even 20th century kitchens have been modernized and hence these photographs of original kitchens in three houses is a rare archive.

Mathebe Aphane and Kees Somer delve into the history of Atteridgeville Township in Pretoria in another important chapter. Jan Jacob de Jong was the Dutch–born architect of the Pretoria City Council and was responsible for the design and planning of this model township. It was all part of the apartheid social engineering, but there was a pre-war segregationist history when there was some experimentation in materials and design. By the 1950s, design seems to have degenerated into cost efficient ‘standardised’. People were pawns in the hands of government and over 10 000 family homes were built. The emphasis fell on regimenting black people to live away from white suburbs so that they could be labouring units. Over the township’s history the high ideals of a 'model' slipped badly into the shoe-box labour unit necessity type of house.

Michael Louw has contributed a long complex chapter on technological trends and transfers from 20th century Netherlands to South Africa. How were new materials and new technologies adapted in a hybridised approach that combined innovative technology and traditional materials. This contribution is dense with information and a mastery of the challenges of translating architectural designs into construction in the specific context of the South African climate and landscape as styles and materials evolved. Many detailed examples of technological achievements grounded in fine craftsmanship show that so many major engineering projects depended on the teamwork of architects, contractors, suppliers and educators, but the inequalities in skills and labour efficiencies were all part of the peculiarities of local politics and economics.

Another interesting chapter interlude is Roger Fisher’s study of the Table Bay Harbour and Cape Town Foreshore project. Fisher has made effective use of archival plans and photographs dating from 1935 to 1945 to create an excellent photo essay with erudite text on the Dutch connection in the engineering challenge at the docks. The Foreshore transformed Cape Town. The J C Jongens sketch of the Foreshore makes a handsome set of endpapers.

Johan Swart, in a chapter on tectonic archives, writes about the huge efforts to assemble information, records and plans that constitute this shared heritage in archival architectural collections such as has been painstakingly built by the Department of Architecture at the University of Pretoria to document the 70 identified Dutch archives, many of whom are relatively unknown until the archive has been assembled. An archive is at the core of solid research. I am not sure I understand the word tectonic (a geological term for the earth’s plates) attached to the archives but I admire the examples of the archives photographed and included in this chapter. I hope it is a chapter that raises awareness of the importance of saving architectural archives. Johan’s passion for archives comes through with charm and eloquence.

Mary Lange and Roger Fisher divert into oral history in their presentation of a case study of the work, life and architecture of two Dutch Pretoria architects who settled in South Africa: Hans Wegelin and Gerrit Brink. These architects are now retired, but over long careers made an important contribution to their adopted country. The focus on the intangible in oral histories is a wonderful piece of documentary history. Scholarship benefits when these personal accounts of the architects and their wives Hanneke Brouwer Brink and Lucette Greef Wegelin are captured in interviews supported by photographs. Gerrit Brink was the architect of the NGK Church Wapadrand and the NHK Pierneef Church.

Ben Mwasingo, the manager of the Built Environment Unit of the South African Heritage Resources Agency has contributed a reflective concluding essay. It is diplomatic and polite. He reflects on what it means when the state engages to prioritise heritage both before and after 1994 and the implications for the future. How should the state respond when diverse cultural roots and different national identities demand policy responses that are completely contrary? A good case study is that of the Marthinus Theunis Steyn statue. Steyn was an Anglo Boer War leader and president of the Orange Free State and the presence of a statue on the UFS campus celebrating his life split student opinion. The statue, created by Anton van Wouw, was erected in 1929 with funds collected by the Afrikaanse Studentebond. It too fell to new student opinion and in 2020 was consigned to the Bloemfontein Anglo Boer War Museum. It is a sobering thought as to what to do with heritage survivals that have been displaced from their plinths.

Steyn Statue (Wikipedia)

The difficulty with heritage and buildings is that it reflects many layers of different contributions. Is it possible to create a single national identity? SAHRA has been commanded to try. Nonetheless, this record of the Dutch 20th century architectural legacy, along with the predecessor book on the Wilhelmiens architecture of the 19th century, reveals how important the Dutch presence was in South Africa, not as a colonial power but as a strand in the composition of national identity and then with the Netherlands as a contributor of new waves of skilled professionals.

To quote from the promotional blurb: 'Common Ground reveals the great variety of styles and building types from this period, ranging from buildings for communities, religious practice, banking, industry and civil infrastructure to the evolution of the Pretoria dwelling and low-cost housing. These contributions are also contentious as they relate to the time of the entrenchment of apartheid. Yet these architects’ extant work is an undeniable part of South Africa today and often still in daily service.'

All contributions have been peer reviewed by independent researchers which is an essential part of the process to guarantee quality and to meet the normal expected academic standards for research in architectural history.

The breadth of this book attests to this huge project making a sizeable academic contribution to scholarship. It provides new information, suggests new research leads and as a collaborative effort ensures that many topics and themes have been covered. It does not avoid at least mentioning the debates about colonial penetration and overseas presence in South Africa and the specifics of how the Dutch immigrant architects, builders, craftsmen and contractors made their contributions to the built environment. The book proudly heralds and singles out the shared Dutch heritage and perhaps the missed question is well how did this contribution differ from that of other European immigrant communities – the British, the French, the Swiss, the Norwegians or the Italians - there simply are no comparisons made. Because of the specifics of the partnerships that grow out of cultural exchanges one accepts that there is a particular vantage point. I found the collection of photographs and the careful documentation of the Dutch presence in South Africa quite extraordinary and the book is a brilliant and welcome addition to architectural literature. The book breaks new ground in so many directions and particularly in the study of the archives in the Netherlands written in Dutch or Afrikaans but now opened up to an English readership. However, no attempt is made to compare the Dutch impact with say the British or the American or any other nationality. The task here is to concentrate on the Dutch as an immigrant community that worked hard to make their mark, lead respectable and productive lives and to add to the mix of cultures.

The great strength of the book is that this top echelon of researchers, archivists and architectural historians disseminates original research. Each chapter has new insights, new questions and new information. The book will become a valuable research resource itself. There is an impressive bibliography; sources are meticulously listed in the footnotes and it meets all the criteria for quality academic scholarship.

It is a handsome book in every sense and one the authors, sponsors, publishers and the University of Pretoria can take pride in. In summary, it is a high quality tome that grows knowledge. The target readership will be libraries around the world, scholars in the fields of Dutch cultural studies, students in postgraduate courses and architectural historians.

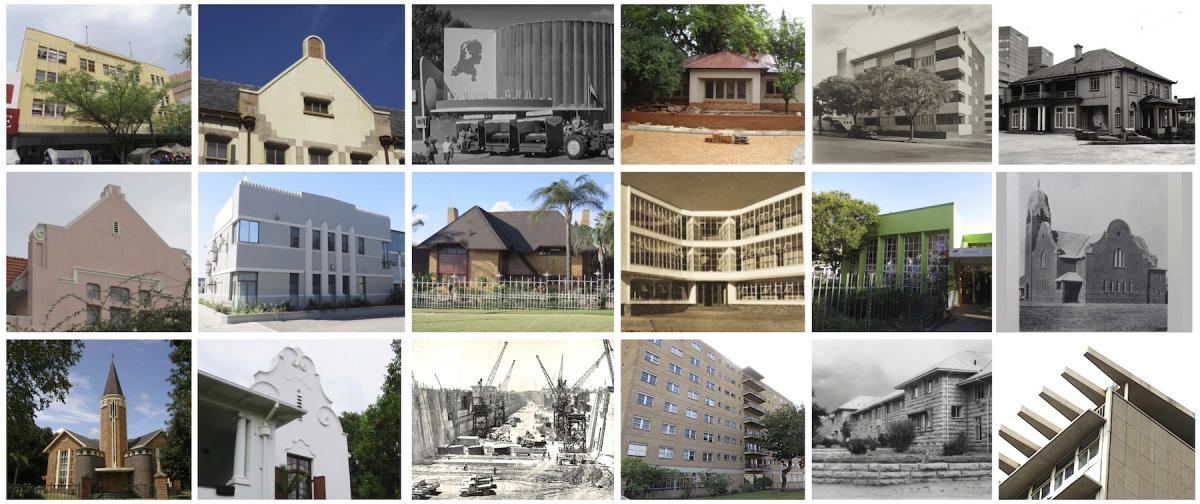

Main image: A collage of the buildings of Dutch 20th century architects in South Africa

Book available from Protea Bookshop in Pretoria. Click here for details.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven.