This book is a happy partnership of two people passionate about architecture and heritage buildings. Together (and with a few additional inputs) they have created a substantial record of 365 buildings from the earliest of colonial times to the present. Shawn Gaylard used his time productively during the Covid pandemic and set himself the challenge of creating a drawing a day, adding up to 365 artworks of South African buildings, bridges and towers. He has the architect's discipline and the artist’s sensitivity in documenting the built environment. His studio is Blank Ink Design and his discipline and passion shines through in this compilation. His selection of 365 buildings for this artistic memorialisation appears to be a personal preference, but as Shawn comments it is only possible to capture the buildings that exist. Whether heritage or contemporary, these are all buildings that you can visit. Shawn’s collection is impressive because it documents a wide and diverse selection of different types of buildings and structures that are notable and have survived. This collection of drawings has been purchased by the Spier Estate and become part of their art collection.

The book is in effect an architectural survey of buildings that have survived from centuries past or have an impressive contemporary presence. Shawn’s partner in this enterprise is Brett McDougall, a heritage enthusiast and someone who has immersed himself in the work of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation over the past decade. It is Johannesburg’s great loss that Brett has relocated to Cape Town, but it is definitely the mother city’s gain. Brett though continues to chair the Joint Plans Committee East of the JHF and in that capacity is an authority on heritage legislation and is an unwavering defender of heritage. Brett has provided the commentaries and background explanations for over 200 of Shawn’s drawings. His captions are succinct and informative.

Book Cover

The first chapter opens with the Dutch colonial era and the first drawing is the Castle of Good Hope built between 1666 and 1679. It introduces the theme that the Cape settlement was dependent on imported ideas and European influences. We instantly recognize the Cape Dutch style as having its origins in the gables of homes and warehouses alongside Amsterdam canals but it is a style that adapted to the local and took root in the farmhouses and towns of the Western Cape, such as Paarl and Tulbagh. Gaylard and McDougall quickly move beyond the European vernacular of the style and remind us to look again at buildings such as the Old Town house in Cape Town or the Koopmans De Wet House where neo classical facades and Renaissance influences were quickly adopted and adapted. But there were other influences too to be spotted in mosques and church architecture. I would have liked a wider selection of 18th century architecture.

The chapter on the 19th century expresses the impact of the British colonial presence in a diversity of buildings such as lighthouses, museums, churches and a city hall. Stretching beyond the Cape there was much to choose from to illustrate how the growth and expansion of South Africa inland and the coming of the railway and penetration through the passes meant new designs in the private and the public sphere. There is no attempt to discuss that interface between different forms of republican and colonial government and their architectural expression and the commercial, business and private domains. Growing wealth through mining meant new opportunities to import European styles. Architects were invariably trained in Britain or the European continent and brought those influences into their designs.

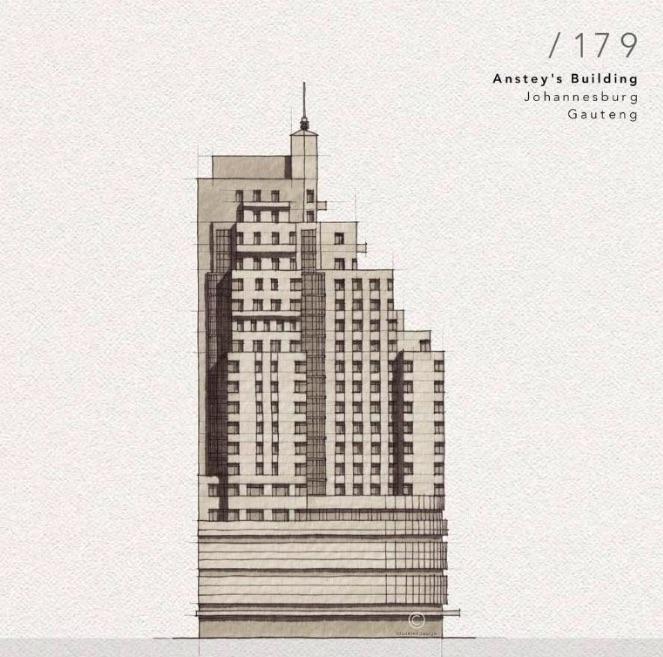

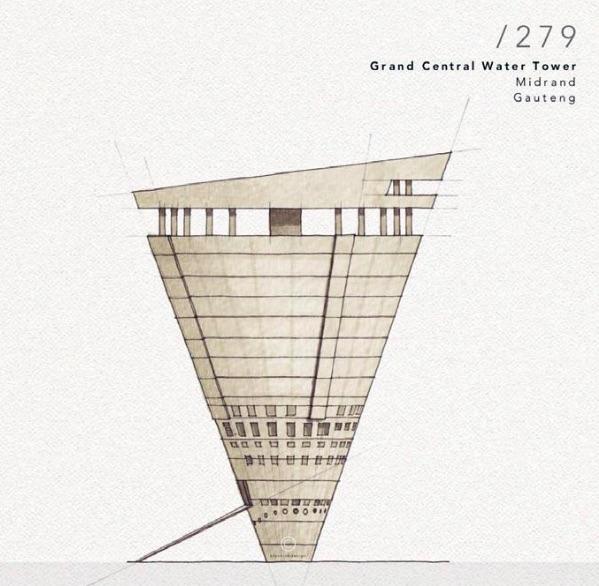

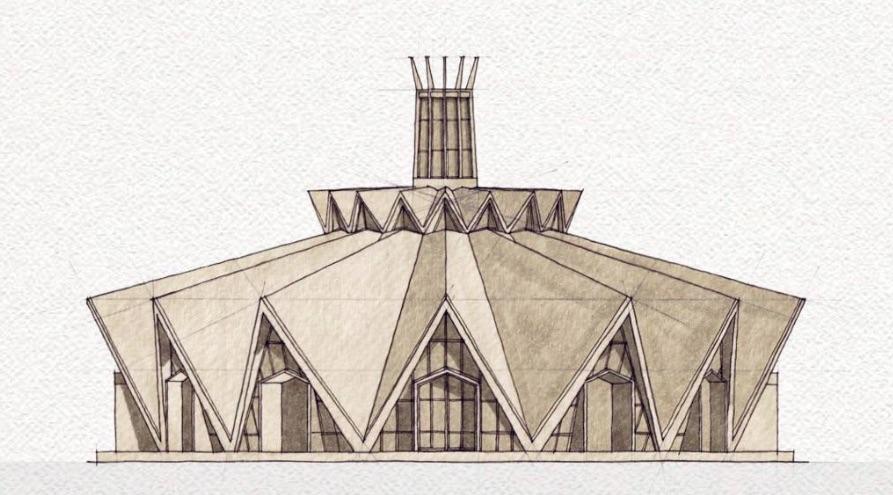

In contrast to the single chapter on the 19th century, there are four chapters on the 20th century and it is this century that forms the backbone of this book. These chapters have been enhanced with essays on specific aspects contributed by specialist architects, Daniel van der Merwe, Stephen Le Roith, Brendan Hart, Brian McKechnie and Yasmin Mayat. These essays add interest and depth and extend perspectives. It was during the 20th century that South Africa, despite the war time episodes and business cycle downsides, moved into what we call modern economic growth and sustained performance with mining investment underpinning city rebuilding. Imported styles could draw upon local construction industries, a domestic steel industry and a local plate glass and tile industry. There is a far greater sophistication and modernity in the styles of architecture whether for industrial, commercial, state or domestic industry. South Africa may be located on the tip of the African continent but the outlook was international and open to world wide influences in architecture - European, North American and even South American. Architects throughout the country were innovative, inventive, creative and sometimes inspired. New complex skyscrapers reaching ever dizzying heights are a marriage of engineering capacity, international styles and perhaps with a local architectural pizazz. South African trained architects of the 20th century could hold their own among the international starchitects.

Corner House

Ansteys

The 21st century is awarded two chapters, bringing this survey up to the present. Overall the volume is very present minded and downplays the heritage aspects, but certainly set me thinking about whether it is simply longevity and the luck of survival that makes for a building achieving heritage status. It remains to be seen how many of the structures sketched for the post 1980 sections will live on to earn respect as iconic and heritage worthy in the future.

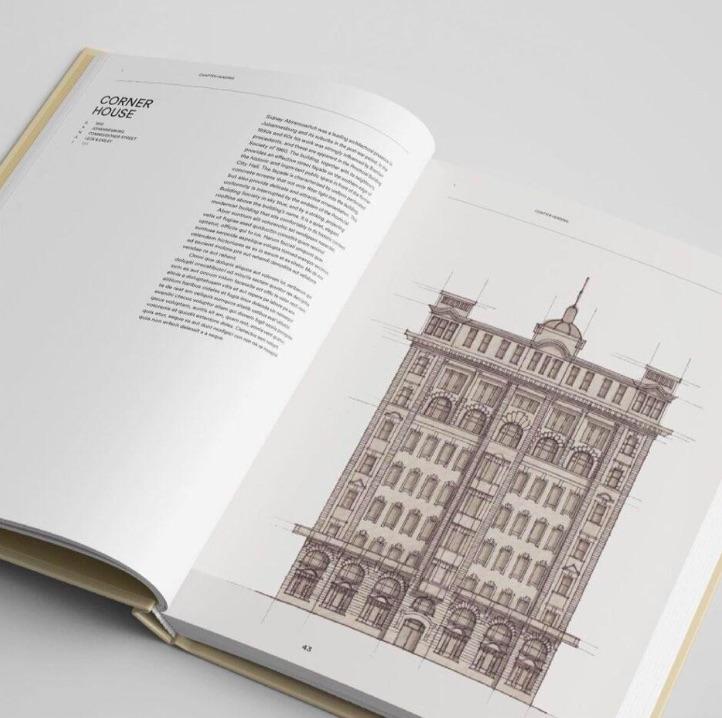

All of Shawn’s drawings are on A4 sheets of paper and some buildings are given in small scale miniature version so that it is difficult to grasp the scale or dimensions of the building. Each of the labels simply gives a date, a location / address and the name of the architect. The brief descriptions of McDougall are just an overview and say little about the technical aspects of construction. I would have liked more information about the builders and the construction firms that made many of these complex buildings possible. Essays by Gregory Katz, Rashiq Fataar and Robert Silke add new voices and a reflection on change and modernity. The crossword puzzle by Coetzee Steyn had me simply puzzled; it’s a superfluous gimmick. A useful bibliography, a glossary and an index enhance the professional status of the book. However, the spreading of a single drawing over two facing pages distracted and detracted from the image of a building as a unity.

In many ways this is an austere book – there are no colour photographs or street scenes nor do the drawings take account of neighbours or the urban context for each building. City streets and the urban are so often messy and crowded. The urban landscape also has to take account of the geographical and geological landscape – the ridges and hills, contours and trees. The focus of the survey is strongly urban with very few exceptions of rural buildings (a blockhouse and a corbelled dwelling have been included). Indigenous architectural and vernacular approaches have not been accommodated in this survey (perhaps the one exception is the corbelled house). This catalogue of the architectural presence in South Africa during the past four hundred years points to the massive impact of colonialism. South Africa may have been isolated at the southern tip of Africa but it drew on imported technology. Slowly over time, a mining revolution, followed by an industrial revolution and only fairly recently an agricultural revolution, extended and embedded local industrial capacity. There is greater confidence expressed by South African trained architects in designs fixed in time and locality. However, the contemporary integration into an international economy, and speedy air transport connectivity means that designs in Sandton could equally be resited in New York, London or Dubai. One huge difference between the three storey buildings of the past compared to the 50 or 55 floor tower blocks of the modern city is the loss of human scale; man is dwarfed by his own architecture.

The book makes a magnificent contribution to the documentation of a range of South African buildings and styles across the centuries, presented to the 2022 reader. It is a proud addition to my library.

Grand Central Water Tower

Book available from the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation - mail@joburgheritage.org.za.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also the Chairperson of HASA.