This book is one of deep research extending over many years. It earned the author a PhD. This is the first comprehensive review of the architecture inspired and financed by the South African state in Pretoria as the National Party regime took charge and pushed their ideas through to shape, refine and implement apartheid in the 1950s and 1960s. Black South Africans were second class citizens and were repressed, whist white nationalists and republicans triumphed. A crowd of 40 000 people gathered on Church Square Pretoria to see C R (‘Blackie’) Swart sworn in as the first State President on 31st May 1961. The photograph of the occasion, reproduced in the book, has an almost messianic quality; winter clothing was the dress (late May can be cold even in Pretoria), all the women wear inverted flower pot hats, all the men are neatly attired in buttoned up shirts, ties and coats. The men do not wear hats; the crowd has the fervency of an open-air church gathering. They could be on St Peter’s square and are welcoming the leader who has delivered the Promised Land. The image conveys an air of people singing from the same hymn sheet, they really believed “unity is strength” but it was an illusory moment, a political chimera.

Book Cover

The new rulers of South Africa after 1948 were politically intolerant and racially prejudiced. They were nationalists, people of faith and confidence. Their moment of victory had arrived after 60 years of bitter regret and hostility carried forward since the Boer War. The standard periodisation runs from the time the National party triumphed in the 1948 election until 1960. In those twelve years the balance of power swung to the Afrikaner nationalists who aimed for a severance of ties with Britain and the coming of a Republic. Afrikaner interests were actively promoted by a government determined to define all in terms of power, strong state authority presented on a platter of modernity. In 1960 the British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, made his “Wind of Change Speech” in the Cape Town Parliament giving due warning to South Africa that Africa was on a path to decolonization and liberation whereas the pursuit of apartheid took South Africa into embattlement and ultimate war. His words were prescient. African peoples all over the continent were claiming independence from their former colonial masters and clamoured for political independence; uhuru was the shout. The response of Verwoerd in his vote of thanks was a polite and gracious thank you but we don’t agree with you and we shall do things our way.

Verwoerd and Macmillan (A Life in Pictures)

How did this fervour translate into architecture and how was Pretoria transformed by an architecture that brought international modernity and the latest of building technologies to South Africa but an architecture that also expressed an ideology. These are the questions tackled by Hilton Judin with a forensic sharp analysis of fact and trend over the period 1957/58 to 1966. Judin breaks new ground; he concentrates on a tight period and gives the architectural legacy a political context. The research is exceptional and the commentary is balanced and even handed. He writes with cool maturity and with a lack of emotion that is admirable.

Architecture in brutalist modern style sponsored by the State reshaped the Pretoria landscape. Judin argues that in this period, buildings took on an ideological role; the visible massive brutalist blocks that were built in these decades marked progress, economic growth, success, triumphalism and expansion. Judin closely examines a selection of significant buildings in Pretoria that embodied the ambitions of the Nationalist government. Theirs was an audacious confident vision. They stood for modernization, industrialization, fast tracked economic growth and promoting the material advance of the minority of South Africa’s population, namely the white racial group. But it was all justified and promoted within a policy framework underpinned by apartheid.

Architecture never exists in a vacuum and one needs to pose questions about the underpinnings of these state structures. What was happening to the structure of economy, investment trends, demographics, manufacturing and industrialization? What was the cost of this new Pretoria and who paid the price? The author references the economic underpinnings of the period but some economic data could have summarised key trends. Of course figures can be boring but the basic demographic data, the structure of the economy by the late 1950s and 60s, the trajectory of the Gross Domestic Product, the pattern of investment and consumption need to be included and analysed in order to explain how an all commanding state had the resources to build South Africa with the vision. The rise of Afrikaner capitalism was only part of the story. During these watershed years South Africa became a Republic, departed in defiance from the Commonwealth, Sharpeville happened, but there were also financial wobbles and a drop in investment for a time. The international financial system still depended on a stable price for gold determined by overseas central banks. South Africa was the primary supplier of gold and there was stability because the price of an ounce of gold was fixed and did not depend on demand and supply. Gold was the primary earner of foreign exchange, the gold mines paid a sizeable share of the taxes, generated the foreign exchange to keep the balance of payments healthy and it was a unholy alliance of the mining capitalism of Main Street and the nationalistic policies espoused on Meintjes Kop. But all was not quite as it seemed as the mines could only stay in business if the low cost migrant labour system, with an unlimited supply of cheap black male labour recruited throughout Southern Africa was sustained and made possible by the State.

44 Main Street (The Heritage Portal)

Judin’s interest is on the architect and his role against the backdrop of cultural nationalism. Judin posits that the Afrikaners pursued modernisation but the backdrop was a latent apprehension about their growing economic prospects in Africa. To carry an argument about vulnerability in Africa means delving even further into the economics and politics of other African countries over that decade.

Judin does not extend to economic analysis but I found I wanted to know a lot more about the finance behind the architecture. I have found as an outsider in researching heritage architecture that architects seldom bother with money; the client is a given and a fee is negotiated.

Nonetheless, one has to be aware that behind the seeming solidity of the capitalist nationalistic state, there were some economic questions about future prospects and where South Africa fitted into the Bretton Woods system. In addition there was political uncertainty as young white teenagers were conscripted and converted into the soldiers of the state to quell the anger and resistance of the black majority. Verwoerd was shot at the opening of the Rand Easter Show in 1960 by an unbalanced David Pratt, but then survived. In 1966 he was less lucky and was assassinated in Parliament. At the same time South Africa industrialized with the share of manufacturing growing to 23 per cent of the GDP. The state had the means to build a new Pretoria to match the visions and Judin explains the architecture of a city and a period.

Young men training for the border (Carol Hardijzer)

Verwoerd Assassination Attempt (Pathe News)

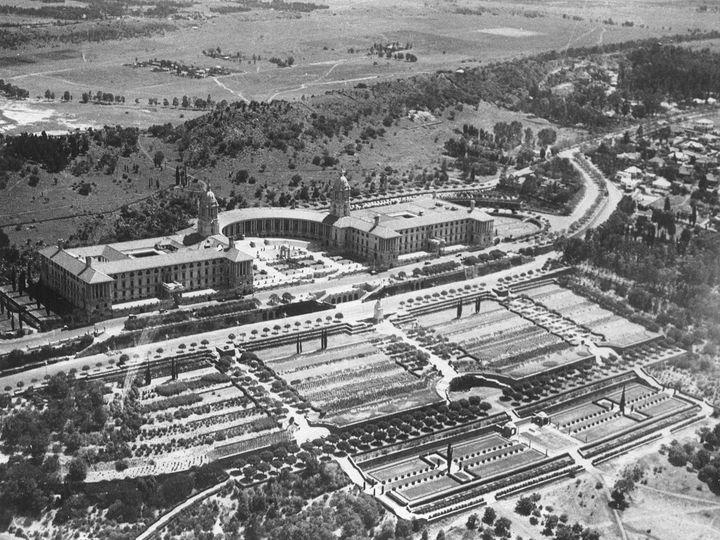

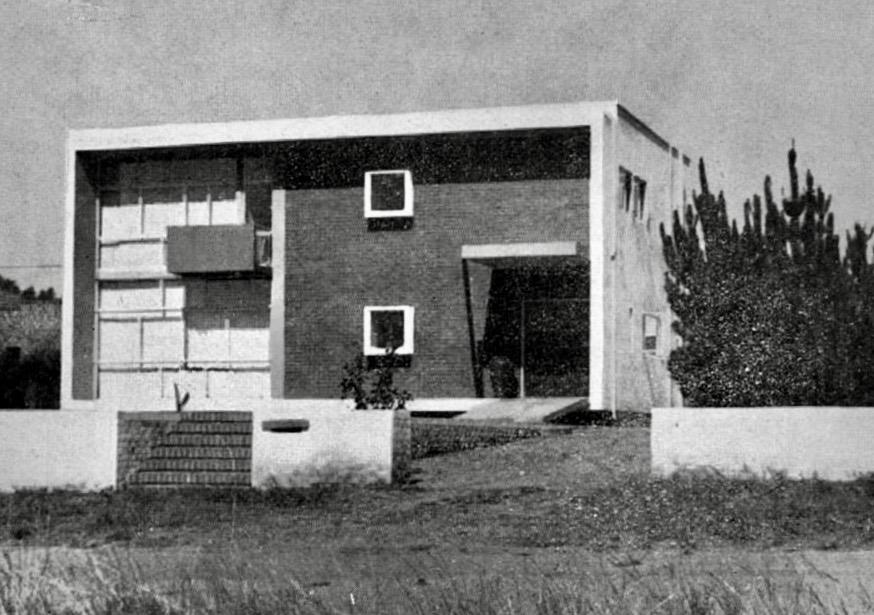

Modernist architecture was not a sudden invention of the fifties. Judin skilfully probes the roots of a modern movement that went back to at least the decade of the thirties when students at universities both in Johannesburg and Pretoria caught the excitement of the ideas of Le Corbusier, Gropius and van der Rohe and rejected the classical traditions of Herbert Baker and his South African acolytes. The earlier architectural styles of Pretoria whether expressed in the great Union buildings complex on Meintjes Kop or the civic architecture of Bloemfontein or the even earlier Dutch influenced Wilhelmiens legacy on Church Square were firmly rejected in the post war period. Architects and their patrons were hungry for modernism and sought new international models - Oscar Niemeyer in Brazil, Alvar Aalto In Finland and Kenzo Tange in Japan – all men whose ideas and influences were absorbed by South African architects many of whom had studied abroad and then returned to invent their versions.

Old photo of the Union Buildings from the air

Old photo of Martiennsen House in Greenside, a modern movement landmark

Judin links Afrikaner cultural nationalism as it found expression in South African architecture. There was space for the local and the vernacular so that the buildings expressed a South African identity. Judin questions where the balance lay – between authentic local identity, a copying of international styles and pleasing the state as patron and client, when the state required obeisance to Afrikaner nationalism. Who were these architects who so hungrily fell for state patronage? Judin fails to enter the debate about who and at what point certain architects stood against the state and stood against apartheid. But that only happened in the eighties and the architects who stood with the Congress of the people at Kliptown in the fifties, men such as Rusty Bernstein, Alan Lipman, Henry Paine and Clive Chipkin did not seek and were never in the running for the work that flowed from Pretoria.

A young Clive Chipkin (Chipkin Family Archive)

This book concentrates firmly on Pretoria with excellent case studies of specific architects and the specific buildings they designed in the city. It would have been useful to have the scene set as to the size, demography and topology of Pretoria. If you are South African of course you know about why Pretoria was the administrative capital of the country and how a bucolic Boer Republic capital with a provincial town flavour came to be at the epicentre of the new Afrikaner republic presided over by Verwoerd as Prime Minister and Swart as President. Nonetheless, the first chapter explains what happened when the Afrikaner urbanized and Pretoria assumed an air of monumentality with its 1948 Voortrekker Monument designed by Gerhard Moerdijk.

Voortrekker Monument (The Heritage Portal)

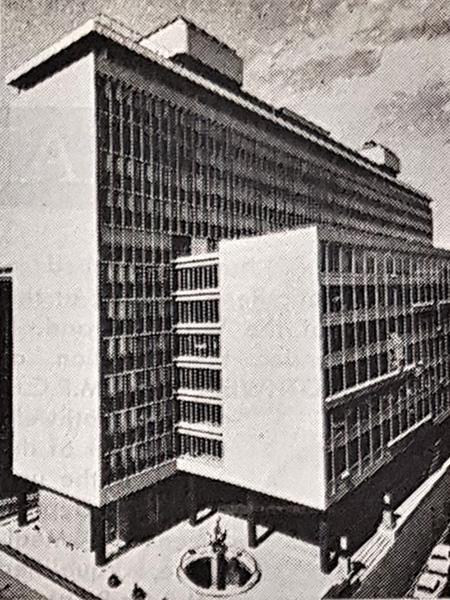

Each architectural project is treated as a case study. The Transvaal Provincial Administration building designed by the collective of Moerdyk & Watson, Meiring & Naude (the partnership combination of Gerard Moerdyk, A L Meiring, Henry Watson and David Francois Hugo Naude). The TPA building was a new civic edifice in the centre of Pretoria that audaciously combined office, warehouse and factory in one. At the time of construction (1960) it was a giant of a building and read as a highly visible symbol of progress. This administrative giant structure for 2200 provincial government staff consolidated 14 disparate provincial departments that had previously been scattered throughout the city. At the time the TPA building was considered to be “a typical and excellent example of a modernist civic building”. On the 11th floor it housed the ‘old Pretoria room’ and many works of art by artists of the time were on show. After the 1994 elections the government seat moved to Johannesburg, modernity faded and the TPA building became a ghost shell, underutilized because of the overt and thrusting expression of nationalist rule. Here is a fascinating account of how a building could express cultural identity that spoke to the ruling class of the day but had no meaning or relevance to the post-1994 government, with a new brand of nationalism.

Old photo of the TPA Building (SA Digest via Artefacts)

Another building that expressed a cultural identity was the Kunsmuseum or Civic Art Museum in Arcadia Park. The architects were Burg, Lodge & Burg with W Gordon McIntosh. Hendrik Verwoerd and the Mayor of Pretoria laid the foundation stone in 1962. Judin sees in this building not just modernist architecture but a reflection of a remade and urbane Afrikaner elite culture. The art gallery was a symbolic projection of a new cultural identity but only of and for the Afrikaner nationalist. Such was the power and collusion of city and state that the largesse of the national state paid for a Pretoria city art gallery. It’s a damning critique but I would have liked more analysis of how the architects saw their brief and why were they such ready automatons of the state.

Old photograph of the Pretoria Art Museum (Wikipedia)

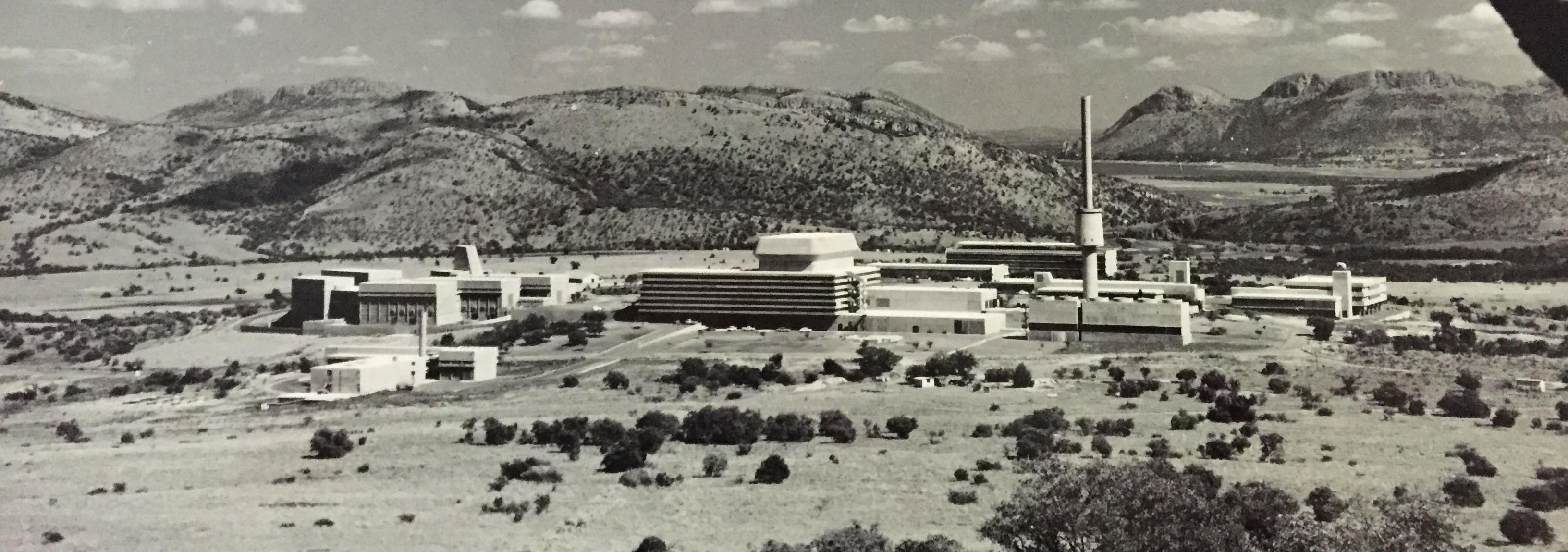

The International Atomic Energy Agency has its headquarters in Vienna. Reading the chapter dealing with the history and architecture of Pelindaba, the South African Atomic Research Centre brought back memories of a late 1990s study tour with my South African students to Vienna where we were shown a model sculpture of the South African nuclear material for an atomic bomb turned into the proverbial peaceful plough shear. Back in the sixties the state sponsored the creation of an atomic energy research centre located on the outskirts of Pretoria close to Hartbeepoort Dam. Today it houses the Nuclear Energy Corporation of South Africa, but in the sixties there was the far more sinister intention of the state to develop the potential to make an atomic bomb. It was the ultimate weapon to protect and defend white fortress nationalist power. Judin does not move too far into that debate but provides an excellent single chapter on the architecture behind this research centre. It was a state enterprise of enormous size and importance. It was also the expression of the partnership of South Africa and the USA in the development of nuclear weapons capacity driven by Cold War realities and paranoia. The high stakes being gambled were hidden behind the sales talk of peaceful applications.

Panoramic view of Pelindaba in the 1960s (NTP Radioisotopes)

Brian Sandrock was the architect of this atomic campus, along with associated project architects, Alewyn Petrus Burger, A C Neethling and Dieter Holm. I found this chapter on atomic architecture to be the most chilling. The result was technocratic monumentalism wrapped in a cloak of modernism on the Highveld. Judin sums up the impact of this monstrous project in a neat way - Pelindaba was the forerunner of the office park and the university research campus. It was a model for government, industry and higher education to collaborate; the legacy menaced the future but also signalled that giant state enterprises driven by nationalist ambitions was an acceptable and moral use of state power. It was a lesson absorbed by the successors to the Afrikaner nationalists of the apartheid era.

There is a specific case study of the Munitoria building (for municipal administration) designed by Burge, Lodge and Burg. Another gigantic monolith building with a message was the UNISA campus building, cut into the Pretoria Muckleneuk ridge, looking like a couple of ocean liners travelling in convoy. They date from the next decade (the mid-1960s to 1973). Here Sandrock made a bold and daring statement about arriving in the City with more than a flourish. I always wondered who actually worked in these university buildings, when after all Unisa was a distance education institution.

Munitoria Building (The Heritage Portal)

Aerial view of UNISA (UNISA)

The administrative wing held all the correspondence material and the administrators to do the dispatching. There were only 530 academics but over 600 administrators filling this administrative wing. I once visited the UNISA library but found that the carpark emptied at 3 pm. I was told though that everyone came to work at 7 am. Judin probes the nature of the architecture and the thoughts of the architects who responded to these state demands for distance education delivered from a central civil service like bunker. Judin feels that the two buildings did not brandish explicit nationalist references. But surely that combination of technological solutions and bureaucratic social engineering came through in the designs of just these types of building. Again architects in Pretoria were challenged to express cultural nationalism with an unmistakeable nationalistic branding. It was gigantic, all subtlety was lost and it was unforgettable.

The University of Pretoria was an all-white, Afrikaans university for the Volk and exuberant nationalism required a modern campus. Here Judin shows how Brian Sandrock and Meiring and Naude transformed the Pretoria University campus from a traditional red brick and tiled roof composition to a more eclectic modernism shown in a number of new buildings, for example centres for Mathematics and Science, Engineering, Extramural studies, Music and Performing Arts. University buildings became symbolic of progress, educational achievement and cultural identity. However, to carry this argument with even greater force Judin could have compared the Pretoria University campus to developments on other campuses; how different were Pretoria buildings of that era from those erected on the English language campuses in Cape Town, Grahamstown or Johannesburg? In Johannesburg, an expression of Afrikaner identity was the Willie Meyer and Francois Pienaar design for the Rand Afrikaans University (RAU). Or indeed what were the similarities and differences between the University of South Africa (UNISA) and Pretoria? Did this new national triumphalism translate into greater capital investment? There is the assumption that the Afrikaner state was monolithic and the state was the client, but were there not a few dissenting views within the Pretoria University Council? These sorts of buildings were as Clive Chipkin said of RAU, monumental and civic in scale. The mentality of a confident ruling class was that these were buildings meant to last for hundreds of years.

The question of invented and authentic traditions in service of separate development is explored in relation to the work of James Walton, who founded the Vernacular Architecture Society and wrote extensively on subjects such as the African village, corbelled buildings, watermills and farm cottages. Walton arrived in South Africa from England in 1947 and his earlier interest had been in antiquarian studies. Walton was curious and thorough in his research, he was a keen observer who undertook field trips. Vernacular architecture was open to some distortion and reinvention by the apartheid state who sought the kind of ethnographic classification that could be used to impose tribal patterns on artificial urban spaces and places that flowed from the relocation of any racial group who was not white. A L Meiring was much influenced by Walton and ready to bend Ndebele architecture to structures imposed by the so called Bantu authorities. Judin’s analysis is sharply critical of the distortion of traditions in service of apartheid models.

Norman Eaton is perhaps everyone’s favourite architect of the middle years of the 19th century. He is something of a national treasure but his work should be critically interrogated. Judin concentrates on the Pretoria Eaton. Eaton thought deeply about African traditions and what he saw as the charm and beauty of fast disappearing rural villages, destroyed by modernity and urbanization. But the imposition of apartheid, and with it the view that black people were robotic labour units created the nutty border industries but also destroyed the rural idyll. Eaton was curious about things African and sought to incorporate vernacular elements, such as African Ndebele design into his architecture; all of this was much praised in his Pretoria domestic architecture. Eaton was feeling his way towards a local South African style of architecture drawing on the local environment. Judin delicately and sensitively discusses the inconsistencies and schism in thinking about how to draw upon local cultures in architecture. There was a tension between modernism and tradition, between black and white cultures, between policy ideals and practice. There is a telling assessment: “Eaton remained a a pivotal figure in such a direct reinterpretation of the indigenous “peasant” landscape even as it was divorced from any social compact.“

Eaton was the architect of the apartheid era South African Police Headquarters, called the Wachthuis, a massive administrative block. This work raises questions about the responsibility of architects and the functions and ideology of such a problematic building which really was all about state control over the civilians and about the application and enforcement of distasteful and relentless apartheid legislation. Judin lets Eaton off somewhat lightly and keeps him on a high design pedestal. Is there really such a thing as “architectural integrity” when the architect was prepared to accept state commissions and architects were pivotal in transforming the capital city?

Wachthuis (ABLE Wiki)

The final chapter is titled “Hubris: Isolated edifices, state apparatuses and a depleted vision” and first covers the context of Afrikaner nationalism under economic siege in the later fifties and sixties. How should architects respond to the Cold War climate, economic success but also isolation that pushed the country towards greater economic self-sufficiency, determined defiance and new buildings?

Overall this is a deep and expansive study of the architecture of Pretoria and the remaking of the city in a nationalist vision - from the 1950s into the 1960s. The book is well illustrated with numerous black and white photographs but presumably in the interests of economy there are no coloured photographs. If an author is going to catch the attention of a wider international readership coloured images are essential.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also the Chairperson of HASA.