Parktown, Johannesburg was the new fashionable suburb on the Witwatersrand ridge, created in the 1890s. The grand sweep of far views north to the Magaliesberg, the bracing air, the ready supply of koppie stone rocks for building, together with land ownership by a land company that took charge of the essential infrastructure and set standards, made Parktown immediately successful. The affluent mining men and their families could build their gracious palaces and call the new city of gold their home.

The street names of the suburb – Victoria, Jubilee, Wellington, St Davids, St Andrews - are pointers to the a distant time period, the British Empire associations and the empire identity of a new upper class. Florence and Lionel Phillips, top of the list of newly rich Randlords, led the way and built their grand mansion Hohenheim in Jubilee Road.

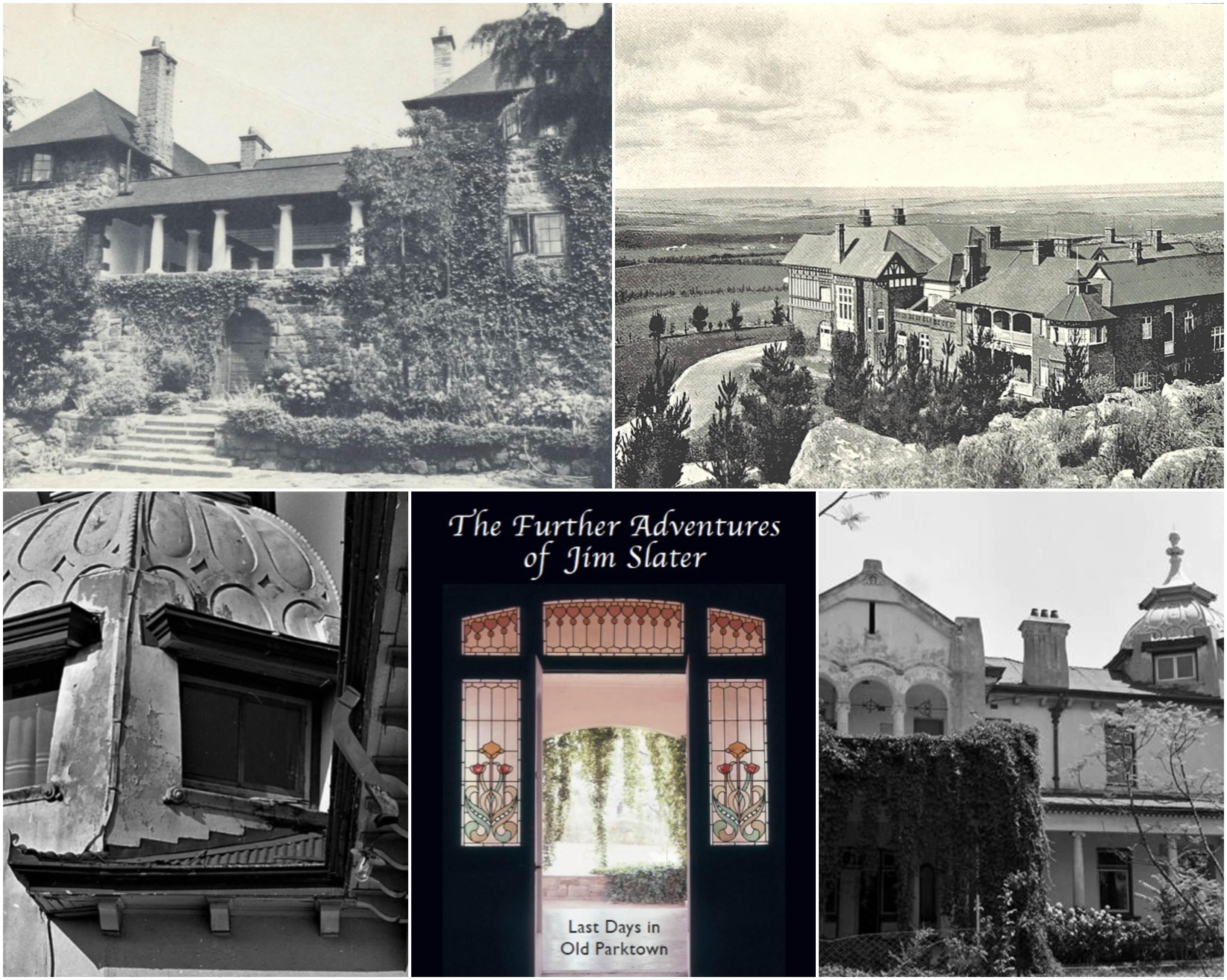

Hohenheim

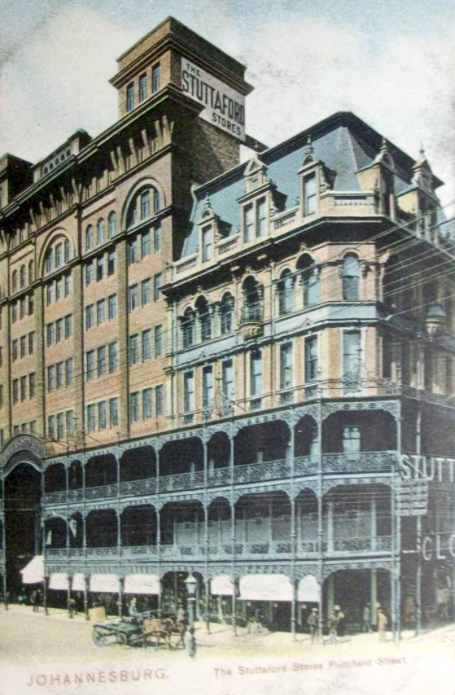

The architectural styles of Parktown were eclectic - essentially Arts and Crafts, French Chateau styles or Mediterranean villas. Parktown with its view sites and high elevations stood in sharp contrast to dusty Doornfontein left behind. Parktown was close to the centre of the city but sufficiently distant to give the residents the illusion that their wealth had brought an airy, hilltop perfection in homemaking. The mansions they built took these newly rich owners back to the sort of life they could only imagine and dream of had they stayed in their home countries; now they were able to replicate the urban villas of such streets as the Rue de Grenelle, Paris or Park Lane, London. Parktown became synonymous with a certain mind set - snobbishly nouveau riche, self-important, ostentatiously grand and very aspirational. There was an oval for cricket on a summer day; private schools popped up for the children and the wives rode by carriage down town to shop at Stuttafords or John Orrs.

Villa Arcadia (The Heritage Portal)

Old postcard of Stuttafords

The grandeur of Parktown lasted into the 1960s, when the property developers, motorways, hospitals, educational institutions and businesses wanted their slice of real estate development. So many Parktown mansions fell to the wrecker. Homes were often too large and plumbing too limited; the lifestyle was obsolete. Parktown was just too desirable and the land too valuable to be kept as a now mature heritage estate. Parktown had become “old Parktown” and the fight was on to salvage a few gems. I picked flowers in the gardens of Hohenheim, as the now derelict, grandest of Parktown mansions waited for the demolition crew to cart away timber, tin and rubble. That some of Parktown has survived as a top residential address has been due to the efforts of the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust who fought to save the grand house legacy of architects such as Herbert Baker (Stonehouse, Villa Arcadia and Northwards), JA Cope Christie (Dolobran), or Charles Aburrow (The View) or J H Aldwyncle (North Lodge).

Stonehouse (The Heritage Portal)

Northwards (The Heritage Portal)

Dolobran (Lucille Davie)

The View (The Heritage Portal)

North Lodge (The Heritage Portal)

Parktown as it was, died before it even reached its century; and today we rely on books, memory and the archive of plans and photographs to understand what it was like to live that life of luxury and maintain that racial and social hierarchy in the world made by the Randlords.

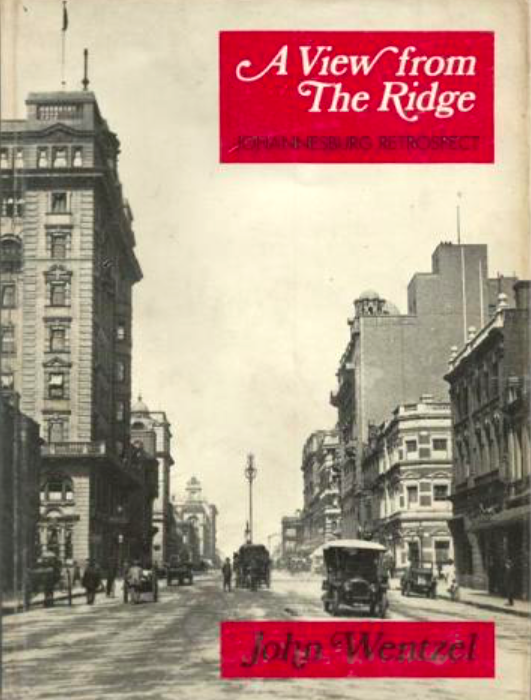

John Wentzel's A View from the Ridge was a lively account of early 20th century Johannesburg

Helen Aron, Clive Chipkin, Shirley Zar and Arnold Benjamin produced the magnificent portfolio of Parktown photographs and a book of essays, Parktown, 1892-1972 that through its very look, size and pale lemon thick pages turned this boxed set into a collectable item from the day of publication. For the suburb's centenary, the Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust produced their well-researched set of 35 pamphlets on the architects, architecture and stories of the people of Parktown, again another collectable archive in a box, with an aged sepia tone to the paper.

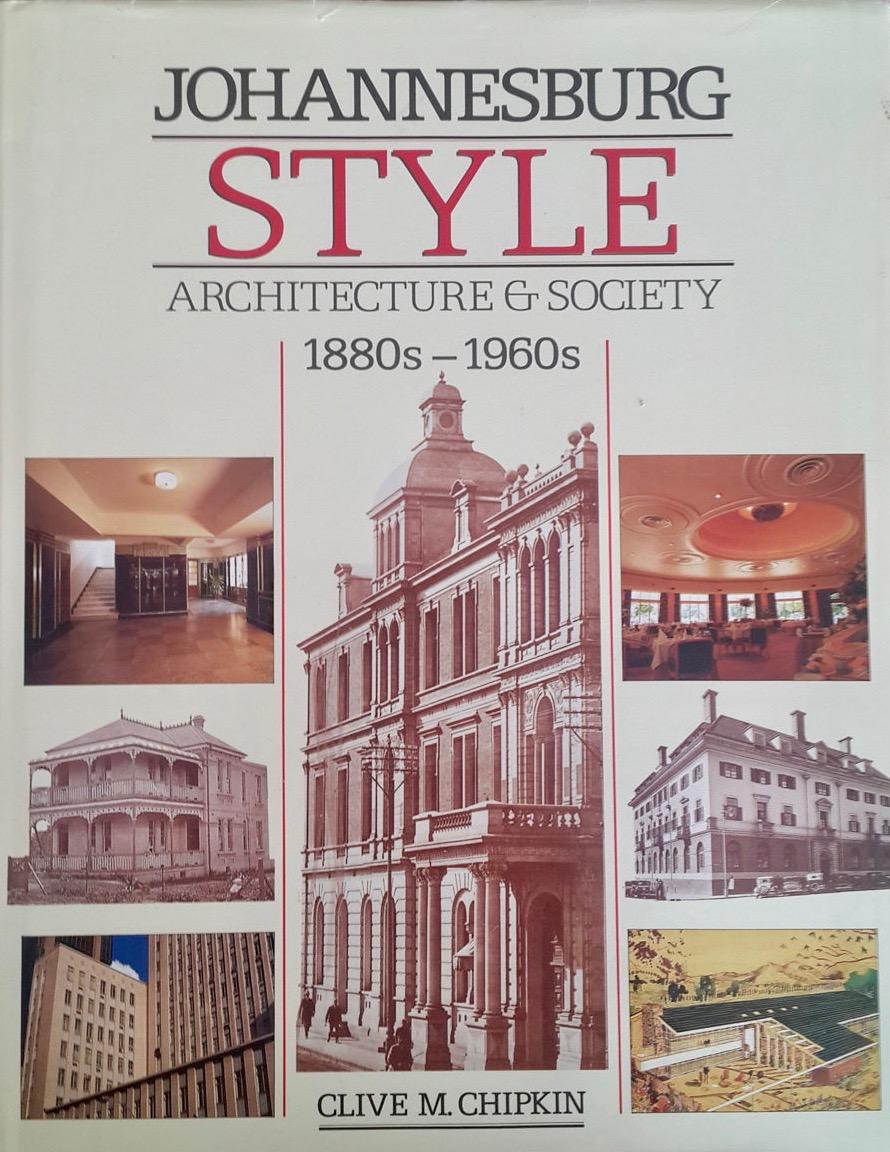

Clive Chipkin, the architectural historian of Johannesburg, told more of the Parktown story and fitted Parktown into the wider Johannesburg canvas in his superb book Johannesburg Style, Architecture & Society 1880s -1960s.

Book Cover

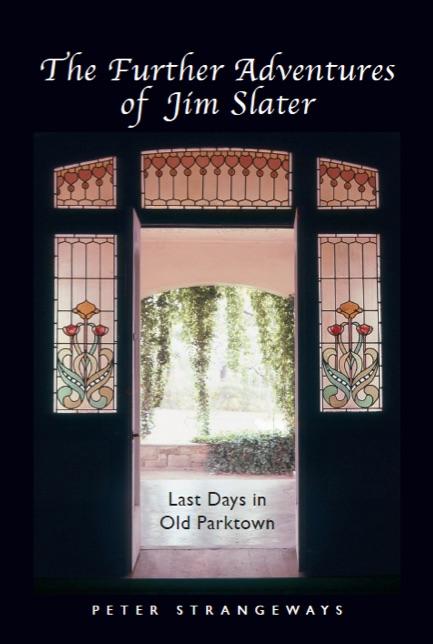

One would have thought that the sadness, and the mourning for Parktown had been well told and Parktown remnants saved in plans, books, and photographs. However, a new book landed on my desk last month that brings the nostalgia of Parktown as it existed in its last days back to life. It is a novel based on fact and experience, set in Parktown in its death throes but so full of life through the antics and life of the characters who populate this book. The Further Adventures of Jim Slater by an unknown author, Peter Strangeways, is a homage to Parktown and adds to the Johannesburg library.

Book Cover

The book is a limited edition (a print run of only 80) hence the high price for a novel but this is an instantly collectable item. For me the photographs of people and old houses set out in the final 20 pages makes this a special and loving memoir and tribute. The photographs are priceless. By the 1960s, Parktown houses destined for demolition and possibly already owned by state institutions, as was the case of the houses on what became the campus of the College of Education and the site of the new Johannesburg Hospital, became available for temporary short-term lets to transient young students or artists. They were fired with the rebelliousness of youth and escaping suburban conventionality. They were long haired hippies, the pot smokers, the flower children, the pacifists, the oddballs of the era who took up residence as the Parktown mansions began to tumble. The now derelict grand homes became filled with temporary sojourners needing a roof over their heads.

Johannesburg General Hospital, now Charlotte Maxeke, was built on the Parktown Ridge

Bob Connolly cartoon framed and in the library at the JHF Resource Centre

For a short time, the echoing rooms were ideal for young people to make homes and communes. They paid rent to “landlords”, they were all white (this was apartheid South Africa with its racially fixed group area demarcations) but they were often penniless. Their favourite music artists were Frank Zappa, Cream and the Doors – way more outré than the Beatles or the Rolling Stones. They also found their own creative voices, making pop art, drinking cheap wine and instant coffee. Parktown’s old homes were ideal for communes, digs and group lets. The large reception rooms became their art and photographic studios. It was a sort of Utopia of the young for a brief moment, a time of caring and enduring friendships. As the demolition teams moved in and the young people moved out, the housing stock of old empty houses diminished. By the mid seventies the era was over and these communities dissolved to reconvene in areas such as Yeoville and Bellevue; but that was another story.

Jim Slater is the alter ego of the author Peter Strangeways; he is an imaginary hero and probably an amalgam of many characters. The novel is delightful because the author paints affectionate pen-portraits of so many Parktown personalities of the day: Helen Aron, Arthur Cantrell, Kenny Alexander, Axel Pederson amongst many others.

Helen Aron (Gail Wilson)

If you were a student at Wits in the sixties, and walked from the campus to Hilbrow or had the pleasure of actually living in a billiard room or even just an attic at a grand address, this book will bring back memories and make you sigh for your carefree youth, old friendships and times past.

The lived experience was Parktown and its mansions and this is what this book is all about. The nostalgia of the author is palpable and he conveys the sense of place at a fleeting time. He looks back on what was a penniless, carefree life filled with love, longing and joie de vivre. A lack of money was a constant problem as these young people moved from one about-to-be demolished mansion to another; the rentals and the landlords were all very temporary. The novel captures the remembered past of a group of friends.

The highlight of the book is the description and photographs of the mansion Friedaura; perhaps one of Johannesburg’s finest examples of eclectic Art Nouveau architecture with curious turrets and towers and glorious twirling tendril gates; the carriage gate would have fitted a Parisian counterpart of the period.

Friedaura (Joshua Spencer)

After demolition, the Art Nouveau gates went to Helpmekaar Meisies (now Rand) school. The mansion was an extraordinary confection; designed by Hermann Kallenbach and his partner of the time, Arthur Reynolds, in circa 1903 /04 (the date on the porte cochere was 1904). The first owner of Friedaura was Heymann Saenger (1959 – 1933), described in his South African Whose Who entry in 1909 as a financier. He was an immigrant from Germany and was educated in Germany and South Africa. In 1889 he married Annie Jacobsohn and they had seven children. A rambling house was perfect for a large Edwardian family.

Detail of turret of Friedaura (Joshua Spencer)

We know very little about Mr Saenger, but Flo Bird (JHF) added that he seems to have been involved in property development, because he bought up land in Prospect Terrace, Parktown (later The Valley Road) but did not build there. Saenger is remembered in a memorial wall at the Braamfontein Cemetery. Friedaura, stood at the corner St Andrews Road and Victoria Avenue, Parktown, Johannesburg - opposite the James Hay House (another masterpiece of its period but also demolished). As mentioned, Friedaura was a quirky Art Nouveau house with turrets, arches, columns, a veranda, stained glass windows, fanciful chandeliers, wrought iron accoutrements. We seldom think of Johannesburg as having many continental Art Nouveau architecture, but this was one. Alas it lasted for fewer than seven decades.

Hermann Kallenbach was the immigrant German stonemason, architect and expert carpenter who first settled in Johannesburg in 1896 and brought a touch of late 19th century European romance to his style. He returned to Johannesburg after the Anglo Boer War and in a new partnership with Reynolds was responsible for both grand and simple houses and then a number of churches. I have found another of his houses in Seymour Avenue and he was the architect of several churches in Johannesburg - the Greek Orthodox Church, the DRC in Fairview and the First Christian Science Church in the city. He was a man of imagination and flair who found his soul mate when he met Gandhi and who with Gandhi went on to purchase Tolstoy Farm near Lawley which became the communal home and place of reinvigoration for the passive resisters, satyagrahis of the great civil rights struggle initiated by Gandhi. My guess is that Saenger connected with Kallenbach because the latter too was German with his family roots in the Russian empire (today’s Latvia).

Statue of Gandhi and Kallenbach in Latvia

Marvelous photographs of Freidaura have been provided by Joshua Spencer (see above) who by a strange coincidence was a photographer who lived in Parktown at the same time as Peter Strangeways. I can only assume that he was a friend of the late author. Joshua has generously given his archive to the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation. For him it was an unforgettable experience to live in five Parktown houses in as many years. Places scattered through old Parktown but now no more.

East Elevation of Friedaura Parktown (Drawn by Joshua Spencer)

Few of the young people creating those communities and communes in Parktown, thought about the fleetingness of the moment and that their residence in a dying debris of Parktown would pass into the mists of time. A good photograph captures so much – it becomes the record and confirms the memory. Photos, memories and pen thumbnails become the essence of heritage. Joshua Spencer describes Friedaura as “a curious mansion that struck one as unattractive but soon won the affection of all who lived there with its oddities and decaying splendour”. I found the novel warm and generous in spirit. The novel shares a slice of history. It is a tribute to youth, love, life, friendship and to Parktown.

I longed for the author to go beyond the friends and characters of this adventure story. I wanted more history and more architecture. But this is a Johannesburg novel and it is as a novel that should be read. I disagree with the back-cover dismissal of Johannesburg as 'a pretty horrible city’. I think the memoir of Peter Strangeways paints a vivid picture of a corner of an extraordinary city of energy and never afraid to rebuild and reinvent itself. It is my pleasure to add it to my Johannesburg book collection because after all this is an account of life in old Parktown written by someone who was there.

The novel is priced at R320 and can be purchased from the publisher (Square Sail) - 071 610 0326

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials. Kathy is a member of the online book community the Library thing and recommends this cataloging website and worldwide network as a book lover's haven. She is also the Chairperson of HASA.