Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The historical development of the limited liability company is indeed a fascinating one, not the least because depending on who you are talking to and when the discussion takes place, there are likely to be different accounts. We can also accept that virtually every country around the world recognises some form of “limited liability” entity that can be used to carry on business. We will in due course produce an appropriate piece for the Heritage Portal that deals with this issue.

But in this article on “Cases that Shaped South Africa” we are going to look at the cases that have dealt with a particular aspect of company law, namely that a duly registered company has a legal persona which is separate and distinct from its shareholders.

Until recently, when the promulgation and coming into operation of the Companies Act 2008 on 1 May 2011 finally severed the umbilical cord, there was a close link between company law in South Africa and that enacted in the United Kingdom. It is for that reason that some of the cases that shaped South Africa, especially in the area of company law, are actually decisions of a court in the UK. This statement holds true for two out of the five cases we mention briefly in this article.

We start off with Salomon v Salomon and Co Ltd [1897] AC 22 (HL) where the liquidator of a company tried to block the payment of the proceeds from a realisation (sale) of the assets of a company that was being wound up to the holder of the company’s debentures whose claim on that account ranked ahead of the ordinary unsecured creditors of the company. Mr Salomon who had carried on business as a leather merchant had formed a company in which he held the vast majority of the shares (his wife and children each held a few shares because the English law at the time required a company to have at least seven members). He had created 20,000 debentures (a form of secured loan) as part payment for the purchase price of the business which he transferred to the company.

The liquidator, alleging that the company was a mere alias or agent of Mr Salomon, claimed that Mr Salomon was liable to indemnify the company against the claims of ordinary creditors, and that no payment should be made on the debentures held by him until the ordinary creditors had been paid in full. The liquidator succeeded in the Court of Appeal. It held that the company was Mr Salomon in another form who employed the company as his agent. In consequence the company was entitled to be indemnified by him.

Royal Courts of Justice which houses the High Court and Court of Appeal of England and Wales (Wikipedia)

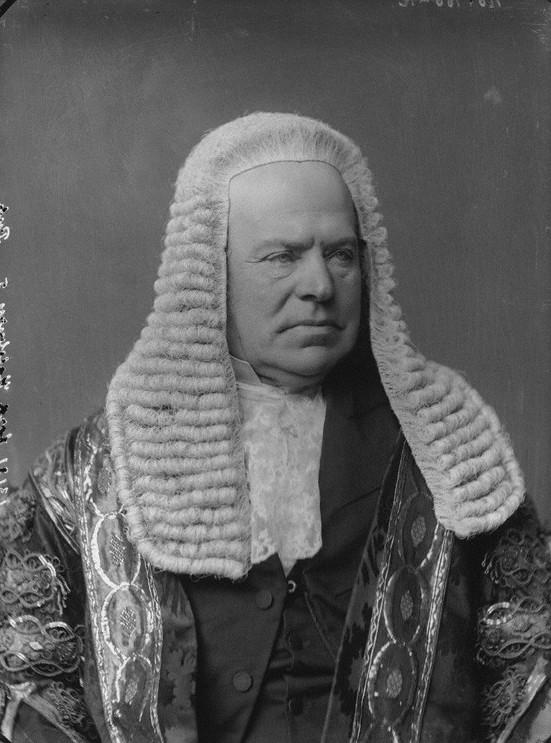

On appeal, the House of Lords reversed the decision of the Court of Appeal with Lord Halsbury LC stating:

...it seems to me impossible to dispute that once the company is legally incorporated it must be treated like any other independent person with its rights and liabilities appropriate to itself, and that the motives of those who took part in the promotion of the company are absolutely irrelevant in discussing what those rights and liabilities are.

And later he stated:

Either the limited company was a legal entity or it was not. If it was, the business belonged to it and not to Mr Salomon.

Lord Halsbury (Wikipedia)

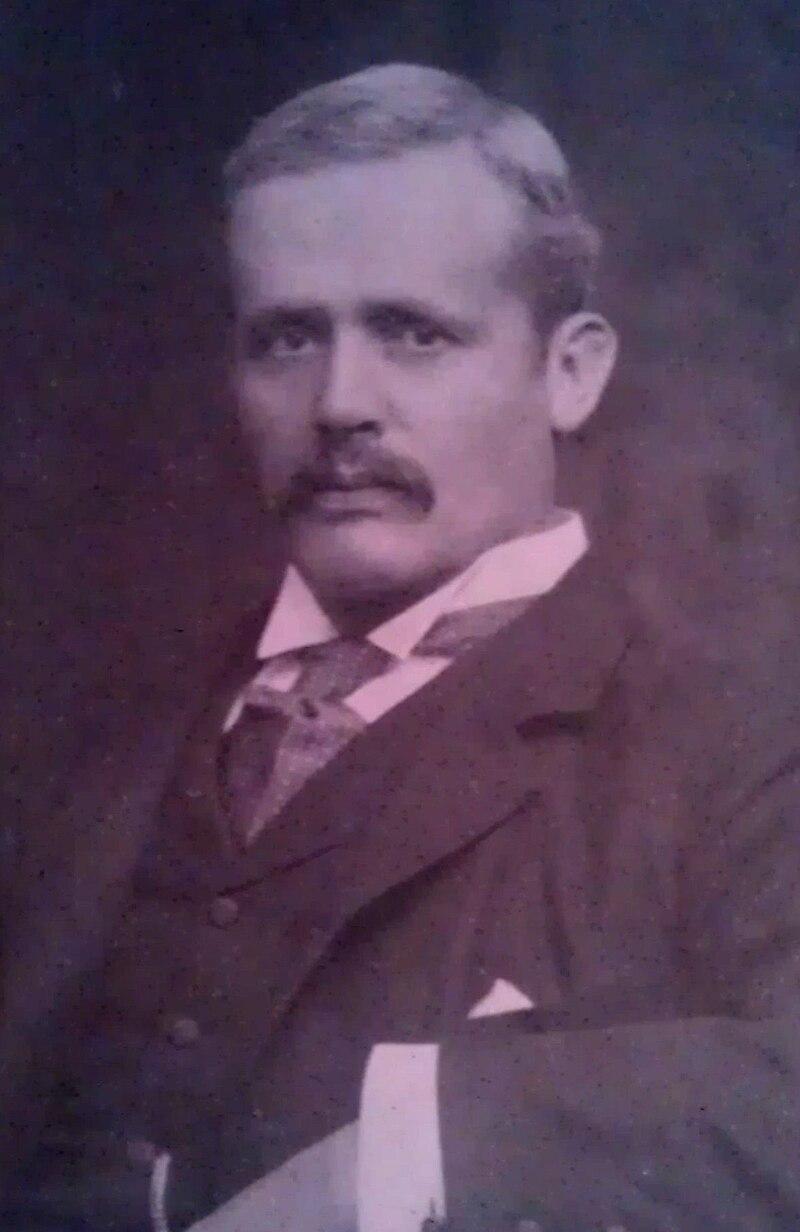

In the same case Lord McNaughten also poured cold water on the view that must have been advanced at the time that there was something amiss with the so-called “one man company” when he declared:

It has become the fashion to call companies of this class “one man companies”. That is a taking a nickname, but it does not help one much in the way of argument. If it is intended to convey the meaning that a company which is under the absolute control of one person is not a company legally incorporated, although the requirements of the Act may be complied with, it is inaccurate and misleading; if it merely means that there is a predominant partner possessing an overwhelming influence and entitled practically to the whole of the profits, there is nothing in that that I can see contrary to the true intention of the Act or against public policy, or detrimental to the interests of creditors.

Lord Macnaghten (Wikipedia)

Before we proceed, a word of caution: in a future article we will examine cases where the courts have, in appropriate circumstances, by employing the technique of “lifting the corporate veil” gone further into the ownership of a corporate entity. But for now we are fixed on the distinction between the company and the shareholders - who each hold a separate legal persona.

Coming to South African shores the leading case on this issue is Dadoo Ltd v Krugersdorp Municipal Council 1920 AD 530, where Chief Justice Innes pronounced:

A registered company is a legal persona distinct from the members who compose it... Nor is the position affected by the circumstance that a controlling interest in the concern may be held by a single member. This conception of the existence of a company as a separate entity distinct from its shareholders is no merely artificial and technical thing. It is a matter of substance; property vested in the company is not, and cannot be, regarded as vested in all or any of its members.

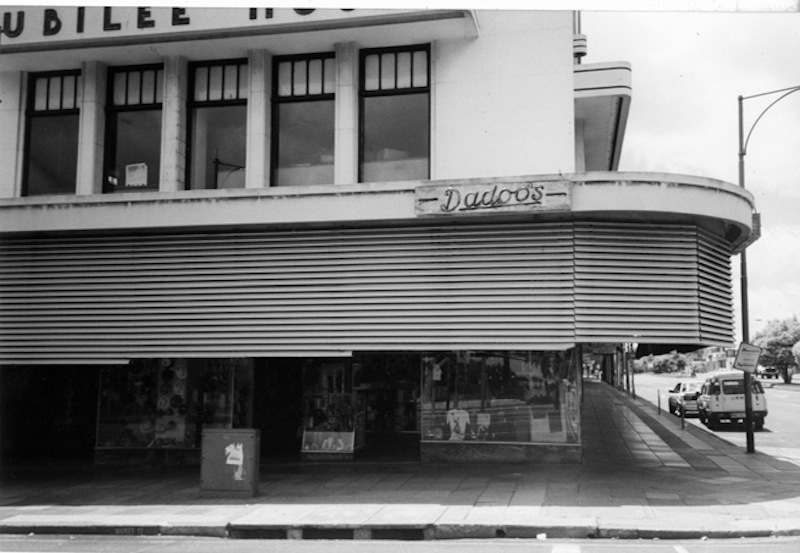

Jubilee House, one of the properties owned by Mr Dadoo (Roshan Dadoo)

In Dadoo’s case the question was whether a statute that prohibited ownership of immovable property by persons of Asian descent meant that the same prohibition applied to a company whose entire shareholding was owned by Mr Dadoo (149 shares) and Mr Dindar (one share) both of whom were Asians. It follows from Innes's reasoning above that the Appellate Division (as it was called at the time) upheld the principle that the company had a legal persona of its own which was independent of the persons who held its shares.

Chief Justice Innes (Wikipedia)

Our other United Kingdom case also provides a good practical example of how the principle is applied.

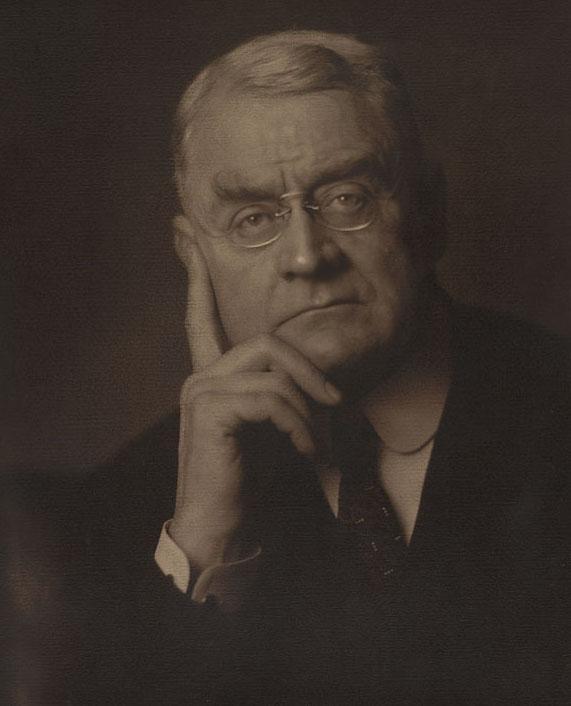

In Macaura v Northern Assurance Co Ltd [1925] AC 519 (HL(Ir)), Mr Macaura (the appellant) was the owner of a timber estate. He sold the whole of the timber to a company known as the Irish Canadian Saw Mills Ltd, the total amount to be paid to him for the timber being £42,000. Payment was effected by the allotment to the appellant or his nominee of 42,000 fully paid £1 shares in the company. No further shares than these were ever issued. The company proceeded with the cutting of the timber. In the course of these operations the appellant became a creditor of the company for £19,000. Beyond this the debts of the company were trifling in amount. The appellant insured the timber against fire by policies effected in his own name. The timber was destroyed by fire. The insurance company refused to pay out on the ground that the plaintiff had no insurable interest in the timber. The Court agreed with the contention of the insurance company.

Lord Sumner agreed that it was clear that Mr Macaura had no insurable interest in the timber since this belonged to the Irish Canadian Saw Mills Ltd of Skibbereen Co Cork. He had no lien or security over it and, though it lay on his land by his permission, he had no responsibility to its owner for its safety, nor was it there under any contract that enabled him to hold it for any debt that the company may have owed to him. He owned almost all the shares in the company, and the company owed him a great deal of money, but neither as creditor nor as a shareholder, could he insure the company’s assets. The debt was not exposed to fire nor were the shares, and the fact that he was virtually the company’s only creditor, while the timber was its only asset, made no difference to the learned Judge.

Lord Sumner (Wikipedia)

Mr Macaura stood in no ‘legal or equitable relation to’ the timber at all. He had no ‘concern in’ the subject insured. His relation was to the company, not to its goods, and after the fire he was directly prejudiced by the paucity of the company’s assets, not by the fire and he accordingly had no insurable interest in the timber.

As a consequence of this recognition of the separate legal persona of a company there has also been a string of cases in South Africa where the Courts in South Africa have held that the legal persona of a corporate entity was entitled to protection of its good name and reputation just as any natural person would be. Accordingly a corporate entity can bring an action against a person who allegedly makes a defamatory remark about the corporate entity. These cases include:

- GA Fichardt Ltd v The Friend Newspapers Ltd 1916 AD 1;

- Universiteit van Pretoria v Tommie Meyer Films (Edms) Bpk 1979(1) SA441 (A);

- Dlomo v Natal Newspapers (Pty) Ltd 1989(1) SA 945 (A);

- Caxton Ltd v Reeva Forman (Pty) Ltd 1990 (3) SA 547 (A)

Fichardt was the first case in which questions of the kind mentioned in the cases referred to above were discussed in the Appellate Division. The appellant company, a trading corporation, claimed damages for defamation, alleging that it had been defamed in headlines to an article which appeared in a newspaper owned and printed by the respondent company. Innes CJ said (at 5/6):

That the remedy by way of action for libel is open to a trading company admits of no doubt. Such a body is a juridical persona, a distinct and separate legal entity duly constituted for trading purposes. It has a business status and reputation to maintain. And if defamatory statements are made reflecting upon that status or reputation, an action for the injuria will lie. (See de Villiers' Law of Injuries, p. 59.) In the present case no special damages were proved; but that circumstance does not really affect the position. Where words are defamatory of the business status and reputation of a trading company, I am not aware of any principle of our law which would make the right of action depend on proof of special damage.

Solomon JA, in whose judgment Maasdorp JA concurred, said (at 8):

It has been settled by a series of decisions, both in England and in South Africa, that an action will lie at the suit of a trading company for statements defaming it in its business character or reputation. For example it is actionable to write or say of such a company that it conducts its business dishonestly or that it is insolvent. And for defamatory statements of that nature general damages may be given, just as when an individual is defamed, nor is it necessary to prove that actual loss has been sustained. The law on this subject is now well settled, and it is unnecessary, therefore, to discuss the authorities dealing with it.

And just to close off the circle we can draw attention to the fact that section 19 of the Companies Act 2008 which came into operation on 1 May 2011 effectively provides that a company is a juristic person that has all the legal powers and capacity of an individual. Furthermore a person is not, solely by reason of being an incorporator, shareholder or director of a company, liable for any liabilities or obligations of the company, except to the extent that the Companies Act or the company’s Memorandum of Incorporation provides otherwise.

The clearest example of where the Act would “provide otherwise” would be the requirement that the affairs of the company are “managed” by a board of directors who make decisions affecting the operation of the business through the process of considering, recording and passing resolutions relating to the business of the company. And to take this further, it would be possible to restrict the directors from making certain decisions without the approval of the shareholders (such as a decision to sell the major portion of the assets or business of the company). An individual is not required to comply with any such formalities in respect of his or her decision.

Another textbook example would be that while two companies may, again subject to compliance with the procedures regarding shareholder approval (and other regulatory authorities), merge or amalgamate with each other, it is impossible (and impermissible) for a company to marry one its shareholders!

Main image: Supreme Court of Appeal in Bloemfontein (Wikipedia)

This article forms part of a series on cases that shaped South African law. Click here to view other articles and here to pre-order the book. Should you require any further information or assistance regarding the topics we have covered you can contact us at: legaleagles@businessrestructuring.co.za.

Graeme Fraser (BA LLB LLM HDip Tax) and Veldra Fraser are corporate and commercial law consultants who operate under the Company Law Today brand (www.companylawtoday.co.za). We have a passionate interest in legal writing and in particular the collection of cases from South Africa and other jurisdictions. We have co-authored, self-published and marketed over 23 books since 2010 (and there are more in the pipeline). Graeme also wrote "Summit Vision" an account of the lessons he learned creating coordinating and completing the Millennium Big 5 Challenge in the year 2000 : Dusi Canoe Marathon, Midmar Mile Swim, Cape Argus Cycle, Comrades and an ascent to Uhuru Peak on Mt Kilimanjaro.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.