Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

The 100th centenary of the end of the First World War will be celebrated this Sunday 11th November 2018. On the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918 the armistice came into effect; men still poised to fight one another were stopped in almost mid battle in France. Church bells pealed and the guns fell silent. The physical losses had been horrendous. The total number of casualties, through war, destruction, disease, revolution and famine is in reality unknown because the conflict was so widespread. The four horsemen of the apocalypse rode the planet and with possible losses of military and civilian casualties topping 40 million the war was among the most catastrophic in human history; that figure includes military deaths of between nine and eleven million on both sides of the conflict. One has only to travel through the battlefields and cemeteries of northern France and Belgium to grasp the enormity of the catastrophe and the tragedy of loss of a blighted generation. We still remember today with our gatherings at cenotaphs, we place wreaths against war memorials all over the world and wear poppies to remember men and women who died in the conflict. It was truly the Great War.

Johannesburg Cenotaph (The Heritage Portal)

Gathering at the Cenotaph (The Heritage Portal)

The end of conflict meant the coming of peace of a sort; it was almost an interregnum and two decades when the world staggered on to the next war. The soldiers who survived returned to their home believing the empty promises of rewards of “homes fit for heroes”; instead there the aftermath of war brought labour conflicts, strikes, civil wars, the overthrow of empires and post war inflationary pressures. The world was impoverished and the old order was in its dying throes. The United States whilst joining the conflict relatively late with the dispatch of troops to Europe and the loss of over 100 000 men in battle gained the most from a strategic and political perspective. World authority and dominance had passed to the USA before the onset of war, but the War consolidated the geopolitical position of “the new world“ and ushered in the 20th century as the American century.

Political extremism whether in the form of communism or national socialism or fascism seemed for many to offer the real hope of a new world order. The statesmen and leaders gathered at Versailles to hammer out an imperfect peace treaty and the world began to reflect on what had caused the war. Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points became international flagpoles to justify the conflict and anodyne slogans such as “fighting to make the world safe for democracy“ gave a justification and comfort. Small nations were promised self-determination but it could not be delivered on. What did it even mean. With the collapse of empires and the irreversible weakening of the British Empire, it was this sloganeering that fed promises for new nationalism and new countries in the making. The League of Nations was a tentative framework on which to hang the possible resolution of future conflicts but the United States did not join when the American Congress failed to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. Thus the world was left a more disorganized and uncertain place in the wake of the First World War and ultimately the even greater catastrophe of the rise of Hitler and the Second World War followed. The end of World War 1 ushered in a century of warfare rather than a capable international architecture for lasting peace.

Were there any positives that flowed from the First World War? We can cite numerous examples of advances in technology, medicine, science and its applications, optics, transport, and industrial capacity. There was a certain creative destruction that gave the world the modern automobile industry and advancements in flight, radio and television. Creative destruction meant a more powerful armaments industry as countries sought to rebuild their armouries, eschew disarmament and rearm in readiness for that second great war. Ironically the technological gains were part of the whole. Industrialization advanced and that very force that enabled the mass destruction on the battlefields of World War 1, continued to shape massive iron and steel industries in all countries aspiring to develop and modernize and so the thrust to rebuild armies, battleships and air forces quickly defined modern economies between the wars.

The consequences of war were also compounded by the outbreak of the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918 and 1919, which in all probability killed between 20 and 40 million people. Known as the Spanish Flu it was a pandemic experienced throughout the world and wiped out more people than the war itself. It particularly ravaged the 20 to 40 year old age group, exactly the age cohort so heavily sacrificed in war.

The personal family circumstances were changed for so many; the widows and orphans needed to be cared for; women who had gained a toehold in the workplace still did not have the vote. It was only in 1918 that women over the age of 30 gained the vote in Britain. In South Africa it wasn’t until 1930 that white women gained the franchise. But war, and loss of their menfolk meant that women after the war were so much more independent, often not through choice.

The First World War generated an enormous literature. This was one of the first wars where the ordinary man (and sometimes woman) wrote about their experiences. With the introduction of mandatory universal education in Britain in the 19th century, it meant that this was the first time an army had gone to war with more than 90 percent of its soldiers literate. This was certainly the case for both Britain and Germany though literacy rates were lower for Russia and the Austro Hungarian Empire. The poets and writers, men such as Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, Robert Graves, John McRae Edmund Blunden, Vera Brittain and Erich Maria Remarque left a legacy that has enabled subsequent generations to share their worlds. Poetry, novels and memoirs all flowed copiously but the writings of the soldier in the trench perhaps scribbled on a postcard and sent home to his mother have given palpable form and voice that survived the war. The memoirs and memories of men themselves have been saved in museum projects. This too was the first war were the newly enlisted man might leave his photograph as a memento for his family. I found it moving to a point of tears to visit the memorial of Menin Gate and find laid as close as possible to a name, not only a poppy and a small wooden cross but also a plastic sleeve containing a life story or a copy of a photograph. This was the first war where men who fought in the ranks had names (and numbers); they may still have been cannon fodder in this war of attrition but they were known. This was the first war where propaganda was used to put pressure on young men to enlist and fight for king and country.

Wilfred Owen (Wikipedia)

DULCE ET DECORUM EST by Wilfred Owen

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Wilfred Owen was killed on 4th November 1918, just a week short of the armistice.

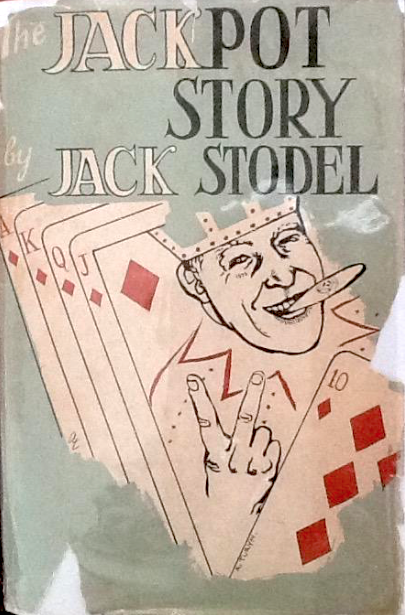

Last week I dipped into a memoir of a South African soldier of the First World War, a book I had never previously encountered, Jackpot Story by Jack Stodel (Timmins, 1965). Stodel was only 15 when he enlisted for the first time in Cape Town in 1914. He was unusual as though only 19 when the war ended he fought in German South West Africa, in the East African Campaign of Smuts and in France. In 1917 he went to England for training and served in the Fifth Battalion Tank Corps in France. This was surely a remarkable record for a South African to have fought in three theatres of war and survived without injury. Stodel returned home to South Africa in the troopship Ingoma. He ended the war as a Captain and went on to a career in films, theatre and cinemas, became a big game hunter, a game fisherman and ultimately a wildlife conservationist.

Book Cover

My own family was displaced, as were many others, and their lives changed forever through 20th century warfare and the flu pandemic. My English paternal grandfather, Sidney Herbert Lucas, was killed in Belgium before my father was even born. My English grandmother, Elizabeth, was left a widow with a baby in arms and remarried not for love but because her second husband, who had also fought in the war and survived was demobilized because his first wife succumbed to influenza leaving five children. My grandmother hence became a step-mother to five young children, the second wife of a surviving war veteran and the mother of my father. She went on to have another three children. All of this created interesting family dynamics and it meant that my father was a loner who enlisted in the Royal Air Force as a young man of 19 and hence came to Africa.

The grave and tombstone of Sidney Herbert Lucas, Oxford Road Cemetery, Ypres. Died 1917 age 29. With grateful thanks to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. (Kathy Munro)

Meanwhile in South Africa, my maternal grandmother of Dutch origin, Dorathea Barbe, who had survived the concentration camp of Bethulie in the Anglo Boer War, was herself a young Boer War widow and then married an Irishman who fought for the British only to be left in 1919 widowed for a second time with seven children in the Free State. Despite being of mixed Afrikaans Dutch descent, her adventurous brother, Frederick Charles Barbe, had enlisted in the S A Infantry, fought and survived Delville wood only to be killed on the Somme in October. My South African Gran endured poverty during the depression years with her seven children. All of this meant that my parents on both sides were forced to educate themselves and neither had the opportunity to attend University.

Frederick Charles Barbe fought at Delville Wood. He was killed at the Bute de Warrencourt, 1916, age 19.

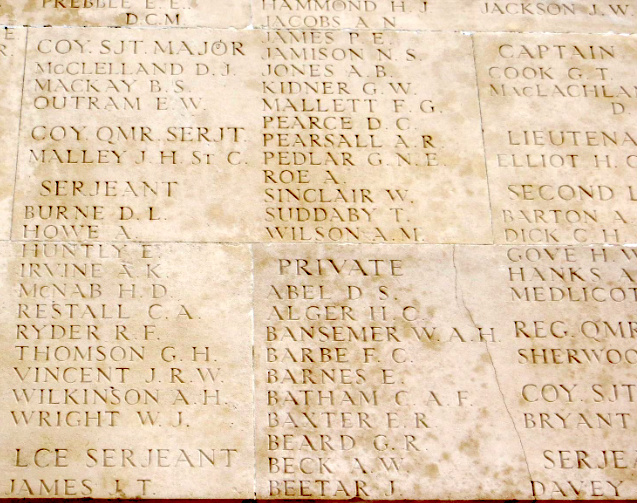

F C Barbe one of the Missing. Remembered on a pier at the Thiepval Memorial (Kathy Munro)

Fast forward 25 years and my mother in turn became a Second World War bride and found herself in war time England with rations, coal shortages and a family of in-laws for whom she was always an African outsider. By the time I was born, only one of my grandparents was still alive. Ultimately the grandchildren of the war generation who finally had the hard earned opportunity to “read for a degree“ (I love that phrase because reading is what education is all about). Here is a microcosm of a single family history. We see the impact of war and pandemic, migration and translocation. My own family returned to South Africa in the year of the visit of King George V and Queen Elizabeth. The legacy of war stays with us for generations. You can imagine the interesting political discussions around our dining room table with this mix of cultures and 20th century experiences in the family history. With an uncle whose name is etched on the Thiepval Memorial (he was one of the missing) and a grandfather who lies buried in a suburb of Ypres, the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War is of personal significance. Wars impoverished both my maternal and paternal families and left the next generation if not entire pacifists certainly with a critical stance on war and the old men who sent young men to fight. I always laughed when I asked my Dad that typical kid’s question “and what did you do in the war Daddy” and his reply came with his dry English humour, “I kept myself alive“.

We weep over a world that takes far too readily to arms despite the experiences of two world wars.

My paternal grandparents from Gloucestershire, Elizabeth Preedy Lucas and her husband Sidney Herbert Lucas who died in 1917 aged 29 at the Battle of Menin Road. He is buried at Ypres. Elizabeth lived to the ripe age of 85. She was the only grandparent I knew.

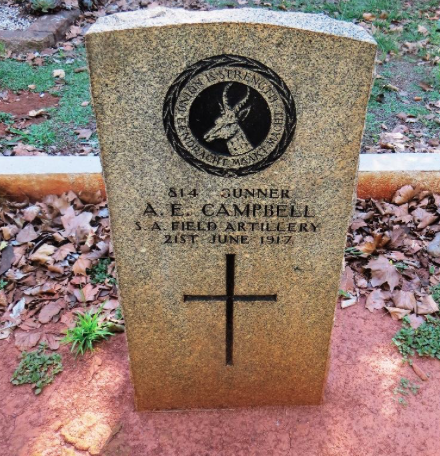

The grave of Gunner A E Campbell, died 1917. Braamfontein Cemetery, Johannesburg (Kathy Munro)

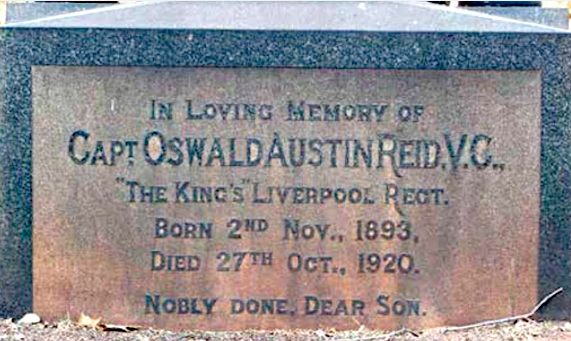

Braamfontein Cemetery Johannesburg. Oswald Reid won the VC. He was a St John’s old boy and died of his wounds in 1920 (Radley Family Archive).

To jump back to the broader dimensions. What about the consequences of the First World War for South Africa? 136 000 men saw service in five theatres of war. It was a white man’s war in the sense that the soldiers were white but it was everyone’s war in as much as coloured and black men were also enlisted to serve in combatant and noncombatant, labouring capacities. The two great disasters for South Africa were the South African military engagement at Delville Wood in 1916 which was a battle in the greater battle of the Somme (5 966 men of all British units lost their lives at Delville Wood and Longueval) and the loss of 649 men of the S A Native Labour Corp and their officers when the SS Mendi sank in the English channel in 1917. The total number of South African military deaths in World War 1 was 12 452 in South West Africa, East Africa, Egypt, Iraq and the Western Front (where more than 4 600 men lost their lives). We remember and commemorate, now 100 years later with tears, medals, memories and memorials on 21st February and on the 16th June and 20th September.

Apart from the loss of men and the flow of blood in battle, the impact of the First World War on South Africa is difficult to assess. Politically it put South Africa firmly on the side of the Allied cause, positioned as a fighting nation in the British Empire. Despite the divisive effect and legacy of the Anglo Boer War still so much then part of recent memory, both English and Afrikaners as well as black and coloured men enlisted to serve. A greater sense of South African nationalism and identity emerged despite the dissent of the 1914 rebellion. The South West Africa campaign against Germany as well as the dispatch of troops to East Africa went ahead. A thorny issue was that while the Union Defence Force was a national defence for the defence of South African borders, men who enlisted to fight abroad did so as part of newly formed units. Emerging nationalism though also meant that the S A Native Congress (the forerunner of the ANC) also sharpened their awareness of a latent innate African political identity and consciousness. Many black leaders who supported the enlistment of men from rural areas believed that support for Britain and a commitment to King and Country would bring later beneficial political dispensations and improved political rights. That this did not happen was a huge disappointment. The other dimension was that war also divided opinion and whilst men such as Smuts and Botha backed the British, Afrikaner nationalism moved to the right and led to the formation of the National Party with its apartheid vision rooted in a different identity and of course with tragic consequences for the country.

The First World War saw Smuts and Botha both taking up an international role and becoming South African statesmen on a world stage. Both became respected military leaders. Smuts was a participant at the Paris Peace Conference. He was the only individual to sign the peace settlements after World War 1 and 2. Smuts was a proponent of the League of Nations and the concept of mandated territories and hence the start of South Africa’s involvement in South West Africa (now Namibia) and the later tortuous Border Wars. South Africa too saw more of its 20th century conflicts rooted in the First World War.

Symbols of remembrance. The Cross of Sacrifice Brixton Cemetery. (Kathy Munro)

Economically South Africa gained in maturity during the First World War. The number of industrial establishments doubled. Leaders realised that the country needed its own substantial iron and steel industry backed by the state. Here were the seeds that led to the establishment of ISCOR.

War though also brought inflationary price rises and since South Africa was still on the gold standard, this meant that the gold produced on the Witwatersrand had to be sold at the prevailing controlled price, regardless of real costs rising. Meanwhile rising costs meant more marginal mines and the pressure on the mining companies to cut expenses, most significantly the labour cost. That in turn led to labour conflict and the 1922 strike so ruthlessly suppressed by Smuts in Johannesburg. Smuts lost the 1924 election, with a result that a PACT government far more nationalistic under Herzog rose to power. Today it is difficult to grasp these nuanced connections to the impact of an international conflict and local actions and reactions but if we probe we see that in addition to the obvious military commitments and consequences there were a myriad of economic and political consequences that impacted on South Africa. Hence we need to reflect on the 11th November not only for that lost generation of men but also on how South Africa’s economic and social history could have been so very different had there been no First World War.

Kathy Munro is an Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and in management at Wits University. She trained as an economic historian. She is an enthusiastic book person and has built her own somewhat eclectic book collection over 40 years. Her interests cover Africana, Johannesburg history, history, art history, travel, business and banking histories. She researches and writes on historical architecture and heritage matters and is well known for her magnificent book reviews. She is a member of the Board of the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation and is a docent at the Wits Arts Museum. She is currently working on a couple of projects on Johannesburg architects and is researching South African architects, war cemeteries and memorials.

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.