Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

In Church Square, Pretoria, stands a statue of President Paul Kruger flanked by four bronze sculptures of Boers. They spent nearly twenty years, from 1902 to 1921, in England before being returned to South Africa eventually to take up their position on the square in 1954. The general belief has been that Lord Kitchener, Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in South Africa from 1901 to the end of the war ‘stole’ these statues as ‘spoils of war’. This view has been espoused by biographers of Kitchener, such as Philip Magnus in 1958 who incorrectly claimed the statues were returned in 1909. John Pollock, Kitchener’s most thorough biographer records that it was ‘opponents of Kitchener in his controversy with Curzon in India [who] had spread the rumour that he had removed “statues of Kruger and other famous Boers from public squares in Bloemfontein and Pretoria”.’ The statues were placed at the Royal Engineer Brompton Barracks in Chatham until 1913 when two of them were removed to Kitchener’s estate at Broome near Canterbury in Kent before all four found their way to Church Square in 1953.

Paul Kruger Statue (Anne Samson)

Statue being installed

The statues had been commissioned by Sammy Marks before the outbreak of the 1899-1902 war, were sculpted by Anton van Wouw and cast by Italian Francisco Bruno in Rome. On completion, they were embargoed in Lorenzo Marques as the war had broken out and were eventually, in 1902 donated to Kitchener by Marks himself. As early as May 1902, Kitchener, himself a Royal Engineer, wrote to Sir T Fraser, the Commandant of Brompton Barracks, offering him ‘four bronze statues of Boers and four bas reliefs for use in a war memorial to the fallen.’ (The Sapper Magazine in Parkhouse) Included with the offer was a sketch of his proposal. A memorial committee unanimously approved accepting the statues at a meeting in October 1902 chaired by Sir Robert Harrison, Inspector General of Fortifications. However, before the memorial to the 431 Royal Engineers who lost their lives in the 1899-1902 war was finalised, the statues became the focus of controversy. One of the bas reliefs Kitchener proposed included the peace talks at O’Neil’s farm after the ‘British army’s ignominious defeat at the Battle of Majuba in the First Boer War’ (Donaldson). This was regarded as ‘a step too far’ for the committee who suggested replacing it with a plaque explaining Kitchener’s donation of the statues. Arguments against including the statues as part of the memorial included creating ‘the keenest feeling of resentment amongst our new fellow subjects’ and was so strong that Major General Sir Elliott Wood who drew the original sketch which Kitchener submitted, distanced himself from the project. He now felt it was in bad taste to put the Boer statues in a British memorial when they had been designed to honour Kruger. Others felt the statues were inappropriate as they ‘represent an armed enemy’ and wondered how relatives of the fallen would feel. It was left to the architect to decide how best to use them.

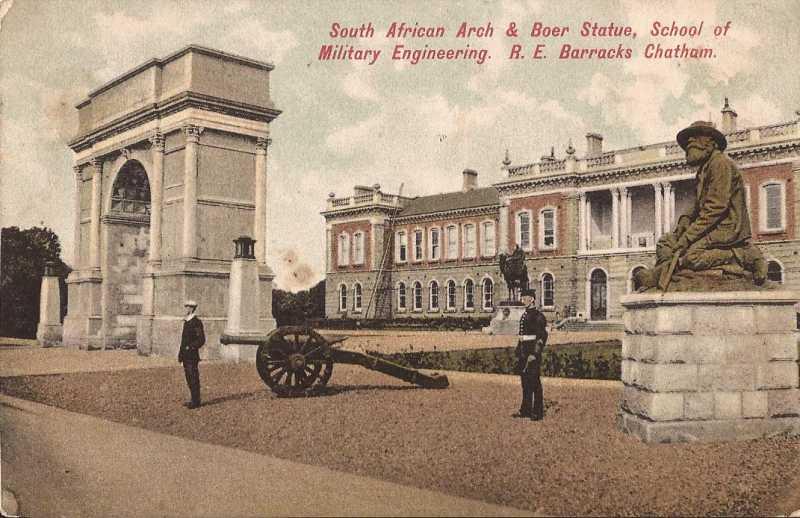

Kitchener was absent throughout these discussions having had a three-month stopover in London between arriving from South Africa on 12 July 1902 and leaving for India to take up the post of Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army. It would have been enlightening to hear Kitchener’s reason for including reference to the peace discussions following the Battle of Majuba. I suspect that having got to know the Boers as he had between 1900 and 1902, he saw no incongruity in including the ‘enemy’ statues in a memorial to the dead. Kitchener had developed a respect for Louis Botha and the other Boer leaders in the lead up to the Vereeniging peace talks in May 1902 being reconciliatory where Lord Milner was not (Kitchener’s first meeting to explore peace with Botha had been in February 1901). Putting Boer and Brit together was his way of recognising the Boer tenacity on the battlefield and reflected the new relationship, one of friendship which would remove future threats of war. However, his views were not sought and the final memorial was a replica of the 1860 Crimean Arch with the statues ‘relegated to a far-flung corner of the parade ground’ where they would not cause offense. The memorial at Chatham, designed by E Ingress Bell, was unveiled by King Edward VII on 26 July 1905 (Donaldson). A photo of the Chatham memorial includes one of the statues – at what stage this was brought in from the ‘far-flung corner of the parade ground’ is not known.

Old postcard of the Memorial to the Royal Engineers, Chatham (via AngloBoerWar.com)

Recent photo of a Boer sculpture (Anne Samson)

In 1910, Kitchener bought his first property, Broome near Canterbury in Kent, and organised for two of the statues to be transferred there where they were erected in 1913, although South African newspaper reports note that Kitchener had one statue and Lord Rosebery the other. This followed a discussion with Louis Botha in London during the Imperial Conference in 1909 about the return of the statues. A newspaper article had intimated they should be returned to South Africa, however, Botha, whom Kitchener consulted, felt there was no urgency or interest at the time. They could remain in England. When a citizen requested in 1910 that the statues be returned, Kitchener refused.

On 24 November 1920, the Transvaal Provincial Council met to discuss the return of the statues following Mr Kretzschmar’s move ‘That the Executive Committee be requested to provide a sufficient sum of money on the estimates for 1921-1922, for the purpose of securing the return to this Province of the four emblematical groups belonging to the statue of the late President Kruger […]’ (Rand Daily Mail, 25 November 1920). In response, Jan Smuts, now Prime Minister of the Union, wrote to Lord Milner, Secretary of State for the Colonies, asking if the statues could be returned to take their place as originally intended. This was felt to be a positive political move, but the permission of the War Office and Lord Kitchener’s heir had to be obtained. The Royal Engineers via the War Office granted permission, as did Kitchener’s nephew, Viscount Broome, who had inherited Broome after Kitchener’s death on 5 June 1916. Pollock records that Viscount Broome having seen Kruger’s statue in Pretoria during 1921 decided with the Royal Engineers to ‘present their statues to the city of Pretoria’ and the Colonial Office arranged their transport. On 30 January 1921 the statues were officially handed over to the Union and People of South Africa by Governor General Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and on 3 March 1921, it was reported that at least two of the statues were on their way to South Africa (Rand Daily Mail).

The statues were finally united with Kruger in 1925, the centenary of his birth, not in Church Square but outside Pretoria Station.

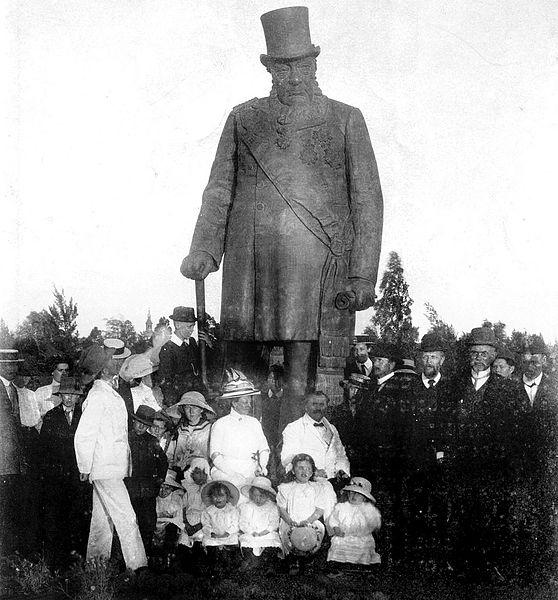

Prior to this, Kruger’s statue was unveiled in Prince’s Park, Pretoria West on 24 May 1913 having been kept somewhere (still to be located) between its arrival from Delagoa Bay in 1906 where it had remained since the 1899-1902 war. (Photo via Wikipedia)

Recent photos of the other Boer sculptures below the statue on Church Square (Anne Samson)

The statues were to be reported on again in August 1945 following the death of sculptor Anton van Wouw, on 30 July, aged 82. Kruger had refused to pose for the artist causing van Wouw to follow him around to get the detail he needed for the project (Rand Daily Mail, 1 August 1945). Another rendition featured in the Rand Daily Mail review of Magnus’ book on 13 December 1958, four years after Kruger and his Boer support were installed on Church Square, the unveiling by DF Malan, taking place on 10 October 1954. In 1964, the South African Digest carried an article entitled ‘Much-travelled statues’ reporting correspondence from the London Daily Telegraph. In this article it was revealed that the two marble lions outside Kruger House in Pretoria had also been commissioned by Sammy Marks who had given them to Kruger. A further revelation was that the Boer statues were ‘found to be hollow and quite light.’

Photo from South African Digest 1964

When I visited Church Square in July 2019 to get photos for my biography on Kitchener, the four statues were still flanking Kruger, no longer freely looking out over the square but fenced in – ostensibly to keep them safe.

Reflecting on the journey of the statues, the four Boers and Kruger and the men who played instrumental parts in their destiny, I can’t but help think that Kitchener’s attempts to bring Boer and Brit together in friendship was realised, at least for some, at the end of the 1914-1918 war. Who, in 1905 would have thought 12 years later Smuts and Milner would sit together as colleagues on the British War Cabinet and discuss the future of four Boer statues?

Another shot of the Paul Kruger Statue (The Heritage Portal)

About the author: Dr Anne Samson is an independent historian specialising in World War 1 in Africa. In 2020 her biography on Lord Kitchener inspired by his reluctance to involve Africa in the Great War of 1914-1918 was published under the title Kitchener: The man not the myth. South African born Anne co-ordinates the Great War in Africa Association, has published widely on aspects of the First World War in Africa and gives an annual talk to the various of the Military History Societies in South Africa when she visits from her home in the UK.

References:

- Donaldson, Peter, ‘Remembering the dead, forgiving the enemy: The Royal Engineers and the commemoration of the Second Boer War’ in Maggie Andrews, Nigel Hunt & Charles Bagot Jewitt, Lest we forget: Remembrance and commemoration, History Press, 2011

- Fraser, Maryna, Johannesburg Pioneer Journals, 1888-1909, The Van Riebeeck Society, 1985

- Magnus, Philip, Kitchener: Portrait of an imperialist, Penguin, 1958

- Parkhouse, Valerie, Memorializing the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902: Militarization of landscape, monuments and memorials in Britain, Troubadour, 2015

- Pollock, John, Kitchener, comprising the Road to Omdurman and Saviour of the Nation, Constable, 2001

- Rand Daily Mail, various

- Samson, Anne, Kitchener: The man not the myth, Helion, 2020

- South African Digest, Vol 11, No 22, 5 June 1964, p16

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.