Disclaimer: Any views expressed by individuals and organisations are their own and do not in any way represent the views of The Heritage Portal. If you find any mistakes or historical inaccuracies, please contact the editor.

From the mid-1940s, the Witwatersrand East Rand and its gold mining and industries were the powerhouse of the South African economy (Bonner, 2000) and these industries drew in thousands of work seekers, fast-forwarding urbanisation in this region and creating a huge struggle for housing and transport. But very few of these hopeful migrants became rich, and many lived in dire poverty and squalor. There were massive systems of conflict. During the 1950s, the area became a focus of apartheid social engineering with the industrial townships of the East Rand seeing forced removals and relocations.

A paper by Bonner (2000) explains the intense upheavals in the area as the very diverse population were forced to deal with the social and political consequences and huge impacts of forced removals. Bonner’s paper highlights the development of an organised youth culture in the area and the extraordinary political mobilisation and mass opposition that came about in response to removals. Essentially thousands of people were relocated from the old location of Dukathole to the new “apartheid township of Katlehong” without consultation or appeal. Bonner’s article also explores the complex interaction of class, urbanity, generation, gender and ethnicity in the Germiston municipality. In the 1950s, trade unionism began to be established within the black political leadership and the populace at large. The Iron and Steel Workers Union, the Dry Cleaners Union and the Glass Workers and the Chemical Workers Union were established at that time, and the South African Communist party and African National Congress became a presence in the area. In other words, this area was a seething cauldron of activism, discontent and stress.

Phil Bonner (via HistoryMag)

Provenance of a long forgotten report

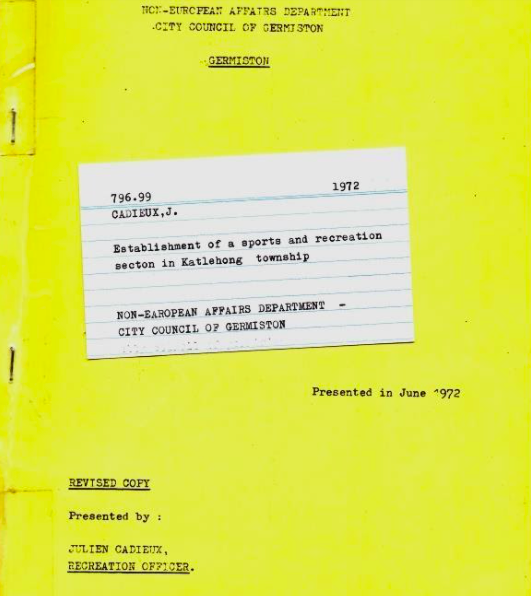

In this essay I investigate the Utopian philosophy evidenced in the forgotten 1972 report by JJ Cadieux. A copy of the report was lodged in the Transvaal Provincial Administration (TPA) library in Pretoria on the 8th October 1979, and still has its library card tucked into a pocket on the inside cover. The author was Mr Julien J Cadieux, a Recreation Officer for the Katlehong Bantu Township. I have a copy of this report, salvaged from a skip outside a government building when the TPA library and thousands of TPA documents and records were discarded in 2003. The rescued document is a foolscap document with a yellow cover and smells mouldy, as old paper does. It also looks as if it had never been opened. This may be the only copy now in existence. The 1972 report by JJ Cadieux was written 20 years after the various racial segregation Acts had become law and only a few years before resistance to apartheid began to accelerate, leading to the 1976 Soweto Uprising. In June 1972, the Non-European Affairs Department of the City Council of Germiston conducted a survey and compiled a report on the Establishment of a Sports and Recreation Section in Katlehong Township, with the work being undertaken by Julien J Cadieux.

Front cover and inside title page of the report 'Establishment of a Sports and Recreation Section in Katlehong Township' by JJ Cadieux 1972.

The world according to the Non-European Affairs Department of the City Council of Germiston

In 1972 the Cadieux report discusses the intentions and findings of a survey he carried out as an employee of the Non-European Affairs Department of the City Council of Germiston. In 1971, the Non-European Affairs Department of the City Council of Germiston formed a new Sports and Recreation Section and a survey of local recreational needs was carried out. In January 1972, a report on the Establishment of a Sports and Recreation Section in Katlehong Township was compiled, reporting on findings. Although the original report was written in 1971, it was revised and released in 1972. What is striking in the report is that, while dealing with the ‘simple’ issue of the provision of recreational facilities in Katlehong, the report quietly strays into the troubled domain of totalitarian social control. It also seeks to ignore the ‘seething discontent and stress’ that was playing out in the region and strides onwards with its idealistic aims for Katlehong’s leisure hours.

The history of Katlehong township

Katlehong township began its history around 1945 as a mixed-race settlement called Dukatole, characterised as a residential area for migrant workers coming to work in the mines. Dukatole very quickly became overcrowded and unsanitary and in the 1940s was declared a ‘black spot’ for forced removal. From 1949, black persons from Dukatole and Elsburg, and many from nearby Edenvale and Alexandra, were relocated to a new township called Natalspruit. At some point in the 1970s, Natalspruit was renamed Katlehong (‘Place of Success’). Katlehong was later fused with two other townships, Vosloorus and Thokoza in the 1970s. The original Bantu population at Katlehong was complex, being mixed Zulu, Xhosa, Swazi, Venda, North Sotho, South Sotho, Tswana, Tsonga and even Chinese, with Zulu and South Sotho being the largest ethnic groups. In the 1970s, the population of Katlehong was around 84 000 and approximately 50% of the population was under the age of 16 years of age. Clearly the area was expanding rapidly, and by 1990, the combined population of Thokoza and Katlehong was well over five hundred thousand people (Kynoch 2013).

Location of Katlehong (Google Maps)

In South Africa after 1948, the National Party government was very determined to control the lives of black people and, while the British colonial government had largely done the same, the National Party put in place a suite of brutal laws that would govern all aspects of the lives of black people. This was ultimately to stay in power as the National Party and in as many ways as possible, benefit white people while keeping black persons as useful, disenfranchised labourers. It would have been important for the government to have a compliant black population that existed as an isolated society, separate from the white population. The apartheid laws that ensure this included the Population Registration Act of 1950 and the Bantu Self-Government Act of 1959, the Group Areas Act of 1950 and Natives Resettlement Act, Act No 19 of 1954. These and other Acts showed the apartheid government’s firm intention that different racial groups were to live separately. Township spatial planning during the apartheid years was in itself a way to assert control over separate urban spaces a way of achieving the full scale of racial segregation.

The Group Areas Act of 1950 and Natives Resettlement Act, Act No 19 of 1954, along with pressure from the National Party government, resulted in an acceleration of the rather piecemeal slum clearances on the East Rand. Slum clearance became forced removals and led to about 60 000 people being forcibly removed in Johannesburg between 1955 and 1960, including on the East Rand. In South Africa as a whole, a further 3.5 million non-white South Africans were displaced between 1960 and 1983 and forced into segregated neighbourhoods and homelands.

Also, interestingly, the 1972 report does not mention any of this ethnicity in relation to the recreational needs survey. The report does note that the races living in the original Dukatole townships were Bantu, Coloured, Indian and Chinese. The Bantu were from all the ethnic groups in South Africa, with the Zulu and South Sotho being the most numerous (Cadieux 1972:3). After the removal of ‘Bantu’ residents to Katlehong, this diversity is reduced to “Bantu workers’, ‘persons’, ‘individuals’ or ‘males and females’.

No time for leisure and sport, even if we had the right clothes

The wrong thinking behind the 1972 Katlehong Survey

The 1972 report states that the Non-European Affairs Department of Germiston and its new Sports and Recreation Section of Katlehong wanted to justify itself as an important public service and thus its work must be carried out within a ‘wholesome and philosophical framework’. The Non-European Affairs Department of Germiston was very keen that planning for recreation at Katlehong should be based on a “scientific approach” whereby the specific needs of the township population were determined through a survey, rather than on various opinions (Cadieux 1972:7). The study was planned and implemented to determine what male and female residents did with their leisure time, and what other activities were desired to fill this leisure time.

I imagine that Julien J Cadieux was a young man and this was his first important assignment. He was the new Recreation Officer, reporting to the Township Manager and was naïve and enthusiastic. His brief included sports, athletics and aquatics, including sports clubs (soccer, ruby, boxing, karate) and swimming pools (Cadieux 1972:29). One has to chuckle at the way Julien Cadieux threw himself into the task of the survey. There may have been tacit instructions from his superiors not to acknowledge any of the political undercurrents in this black community. Cadieux’s superiors in the Non-European Affairs Department of Germiston may have wanted to maintain the fiction of an ‘orderly’ Bantu township society in Katlehong. Thus the report makes no mention of politics, political parties or makes statements about the impoverished surroundings of Katlehong or the rightness or wrongness of the segregation laws enforcing racial segregation. In hindsight we know that there was definitely ‘trouble’ in the townships from the 1950s onwards but political activities were undercover for fear of arrest.

Ignoring major political undercurrents

The report by Cadieux (1972) seems oblivious to the very major political issues underway in South Africa at that time. The Soweto uprising of 1976 was after all only four years away, a product of dissent brewing for some time. There may have been a deliberate decision by the Non-European Affairs Department not to acknowledge black political protest operating beneath the surface of township society. If ignored and excluded, and thus made unseen, black political protect would seem to not exist. The 1972 report is not overtly political or racist and even invokes a reasonable philosophical and scientific approach, perhaps to create an impression of order and truth. The text manages to convey a message of normality, after all how controversial can recreation be? Yet, 50 years afterwards, the text transmits a strange and subtle portrayal of devious and cynical social control. The omission of any social and political references in the final 1972 report also says much about the balance of power in the South African society in the 1970s. Today it would be impossible for a single white person to roam about township schools peddling a survey, but back then, Julien Cadieux’s access was assured by the dominant political regime.

Violence, brutality and stress, South African township style

Cadieux (1972) gives us a glimpse of the intention, through a ‘certain philosophy’ and through the provision of recreation, to inculcate aspects of ‘decent living’ at Katlehong. Recreation is promoted as a “goal orientated way of providing a programme of activities cloaked in a framework of values which will generate intellectual, social and spiritual growth” for the black masses in Katlehong (Cadieux 1972: 5). Recreation was clearly proposed as a form of social control, aimed at creating a “fulfilled society”. The French philosopher, Michel Foucault (1926-1984), would have recognised this immediately. Foucalt’s theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge and the hidden violence of control (Hutta 2019).

Gaps in the 1971 survey

I wonder if Julien J Cadieux realised that the political undercurrents in Katlehong would have been a massive impediment to the implementation of the Non-European Affairs Department’s Sports and Recreation grand plan, and thought the whole idea of recreation futile, but was not allowed to mention this. His first report was issued in June 1971, but the revised version was presented in June 1972 (the report that I have). Perhaps the text had to be further panel-beaten into an optimistic, hopeful and politically benevolent form and troubling aspects left out.

The total number of surveys completed was 3405 and was representative, not of the whole Katlehong population, but a sample of school children over 15 years of age. The Sports and Recreation Section at that time worked closely with schools, school choirs and existing sports clubs in the area (Katlehong African Football Association). The report justified their survey sample by saying that the implementation of any new sports facilities would be done in collaboration with the 31 schools in the township. This already creates a sense of mystery and contradiction. It seems that the municipality wanted to instruct the adult populace about productive leisure, yet the survey did not ask any adult respondents from the general public how much leisure they actually had – an odd admission, perhaps symptomatic of the paternalistic way that the Municipality viewed the black population under its stewardship. Surely it would be the hard-working adults that needed productive leisure activities to help them cope with their busy and brutal lives?

It is highly likely that most of the adults had very little leisure time, especially women. In the report, there was a small disapproving mention of the number of adults who spent their leisure time socialising in their own homes or back gardens (Cadieux 1972:14). This would put them out of reach of ‘state recreation’. Perhaps these persons were suspected of using their leisure time to be involved with political activities.

Hostels and their recreation needs

Cadieux also carried out a survey of recreational needs at the three hostels in the Katlehong Township (Kwesine and Monise hostels and the ‘Compound’) at that time. Hostels are large dormitory-like complexes that were built to house unskilled black, male migrants, primarily employed in the lowest-status urban occupations such as mining, factory and foundry work. Hostels on the Witwatersrand were subject to municipal control until the late 1980s, when they became more-or-less self-governing. In the 1970s, around 7978 male “Bantu” workers resided in these Katlehong hostels, and the 1972 report sweepingly states how these Bantu “were all men who lived in Katlehong temporarily and whose actual home was in the homelands” and in other words were those famous apartheid style ‘temporary sojourners’. In fact, returning to their home in the homelands was probably the last thing these men wanted to do. The main reason they were on the Witwatersrand was to escape from desperate rural poverty and they were prepared to fight for their right to reside in the Witwatersrand urban areas. From Kynoch (2013), we know that the hostel ‘Bantu’ were already strongly ethnically Zulu, and by the 1990s, the Zulu-focused hostels were at war with ANC supporters and fighting for their urban base and at least a chance of survival rather than return back to rural Natal and desperate poverty (Kynoch 2013).

Because these men did not live with their families, the survey says, the Germiston municipality deemed it important to “determine the recreational needs of these men”. However, Cadieux immediately hit a snag. It proved very difficult to win the confidence of the hostel men enough to conduct such a survey and the survey thus took much longer than intended. Each participant had to be questioned individually and with the help of a translator. One develops a suspicion that those long ago hostel residents saw him coming with his clipboard and suddenly hardly anyone in the hostels could speak English or cooperate and became hostile, thus involving Julien Cadieux in a very lengthy interview process. He was forced to put a team of translators together help him. Out of a hostel population of over 7879, he could get only 432 completed questionnaires representing 5.4 % of the hostel residents. Today, one would need a police escort to enter township hostels and ask questions.

Not surprisingly, the survey found that the interest in physical activities was very low in these mine workers because they were exhausted most of the time. Although soccer was a favourite activity, the men actually wanted adult education programmes as well as social and cultural programmes. At that point, there were no such facilities in or near to the hostels. Instead, informal ‘underground’ schools flourished with tuition provided by fellow workers for a fee. There were also no libraries or meeting rooms for social gatherings or facilities for doing arts and crafts (Cadieux 1972:17).

The rather odd survey findings

The survey affirmed that Kathelong at that time was well endowed with ‘standard’ municipal recreational facilities and there were 13 soccer fields, 27 basketball fields, one rugby ground, one softball ground, two tennis courts and three halls, one of which one was used for ‘bioscope shows’ (Cadieux 1972:4). Participation in soccer was found to be the most popular sport activity for youth and adults. Soccer was the only sporting activity that was well organised throughout the townships, with 1368 youths and 1368 adults involved. Boxing was second in importance with an enrolment of 253 youths and adults. Each soccer club had a netball facility for women with a total of 1012 female youths and adults involved (Cadieux 1972:11). The survey did not uncover that perhaps adults lacked leisure time or used their leisure time to participate in political or trade union activity.

Findings indicated that there was a still a need for more recreational activities and implied that it was merely a lack of ‘leadership, facilities and finance’ that was forcing many individuals to postpone their participation in leisure and recreational activities. Even though their main survey consisted of school children over the age of 15, the survey findings inspired the Non-European Affairs Department of the City Council of Germiston to confidently begin planning additional sports and recreational facilities at Katlehong, aiming to proceed smoothly through phases towards, first 1985 and then the year 2000 (at that time a massive 22 years and a social revolution away).

The most popular cultural activities for those over 15 years of age were music and dance, theatre, painting, photography, pottery and sculpture, but only 8.7% of Section I, 10.0% of Section II and 5.03% of Section III and IV participated in these activities, i.e. not a large group of persons. These activities are infrastructures and equipment intensive, but the facilities must have existed in Katlehong at that time. The percentages of the survey group who didn’t participate, but were interested in participating in cultural activities were: Section I 14.2%, Section II 15.3 % and Sections III and IV, 5.3%, i.e. again, not many.

Questions were also asked about hobbies that both males and females over the age of 15 years would be interested in, but not yet able to undertake. These were gardening, cooking, cinema, baking, sewing and knitting, listening to radio, mechanics, reading, stamp and coin collecting, carpentry, again with a total sample size of n = 3405. When asked why they were not already doing these hobbies, the respondents cited a lack of money, the lack of facilities and a lack of skills. None of the respondents were recorded as saying that perhaps they were rather planning to light the fires of social revolution.

Clubs and churches offering recreational activities

A separate survey was distributed to youth associations and churches which ran recreational programmes. The many churches through the township had recreational programmes, mostly orientated towards Bible study, music, games, home crafts, and not sport, but also might have had picnics and camping. Churches with youth programmes included the United Congregational Church of South Africa, the order of Ethiopia’, Thorne Youth, Presbyterian Youth Fellowship, Assemble of God Youth Club, the Salvation Army Youth Corps, Lutheran Church Youth Club, Apostolic Faith Mission and the NG Kerk Youth Club (Cadieux 1972:14). In Katlehong at that time there also were 50 clubs for children and the youth, involving Girl Guides and Brownies, Boy Scouts and Cubs, Wayfarers and Drum Majorettes. There were also a number of women’s clubs: the Family Happiness Club, Beacon Fellowship Education Club and the Katlehong Society for the Blind.

The 1972 report gets even more Utopian

The philosophical framework advocated in the report is that a recreational programme must be built on “sound principles and policies” and must be established with goals which will “entitle [the Non-European Affairs Department] to provide the Bantu population with recreational experiences that have direction and purpose”. The report goes on to say that leisure time was not to be a “mere time-filling pursuit” but must be structured so that “recreation strives consistently and skilfully to satisfy the creative and intellectual needs of people through wholesome and socially sound leisure-time programmes” (Cadieux 1972:5). This implies that the ‘Bantu’ are leading a Utopian existence with an abundance of leisure time. This is a bit of a laugh when compared with the poverty and violence that apartheid was actually offering township populations in South Africa, and also strangely naïve when the violence, political activism and competition between factions, was a major factor of township life in this region.

In addition, the “direction and purpose” of the proposed recreation programme held that “fun, enjoyment and happiness can be allowed as they contribute to socialization, co-operation with an understanding of others, and mental and physical health. Participation in such activities must be part of a personal philosophy in which recreation is important for the way it makes lives of people more enjoyable and more meaningful as an antidote to boredom, monotony and unimaginative existence” (Cadieux 1972:5).

The 1972 report states that the findings of the survey were aimed at “designing a programme for the participation of the individual through group activity” and that was “directed towards the growth of human dignity and self-fulfilment” consistent with the ideas of education in a democratic society, focused toward finding creative and satisfying outlets through a wide range of cultural and wholesome pursuits. Again, this is all a bit of a laugh in hindsight, but perhaps could be considered as part of the ‘invisible brutality’ of the apartheid machine. The recreational programme is also portrayed as ‘sensible’ and ‘scientific’ in that it would “provide means for the individual to maintain good health and physical vitality into to meet the complex challenges of the day” and “show the black population of Katlehong how the use of leisure can be a major force in the enrichment of personality”, again implying that life at Katlehong was just wonderful.

Also, the amenities provision mentioned by the Germiston municipality was to be “cloaked in a framework of values which will generate intellectual, social and spiritual growth” (Cadieux 1972: 6). The ‘cloak of values’ was to be paternalistically provided by the municipality without any nuanced consultation with potential users of the amenities. What is starkly absent from the survey and report is how many hours individuals had for leisure, consider that most adults worked long hours and spent a large portion of each day commuting. What could they have cared about an externally provided programme to ‘enrich their personalities’? Yet the Germiston municipality seemed confident that everything would go according to plan and that the Katlehong populace “would be ready for full participation” (Cadieux 1972:37).

The Bantu are grumbling - let them have more playgrounds

Julien Cadieux’s 1972 report mentions the idea of increasing the number of children’s play lots and creating more “neighbourhood playgrounds and neighbourhood parks” and also of increasing the number of swimming pools, golf courses and sports and cultural centres. One might wonder what these amenities were to be given in exchange for. Though the report does not hint at a trade-off between the municipality and the local community, it may have been thought that these amenities would be in exchange for a compliant populace who were contented with recreation as a form of “intellectual, social and spiritual growth”. This is reminiscent of the type of social manipulation propagated in the Orwellian ‘1984’ government, but in Katlehong, the force behind the scenes element is not ‘Big Brother’, but the apartheid state with its history of deception and media manipulation invisibly at work (Kynoch 2013: 287).

One of the many book cover versions designed for George Orwell's book '1984' published in 1949, about a frightening totalitarian society. Image sourced online.

The Katlehong ‘Ministry of Truth’

In George Orwell’s book ‘1984’, published in 1949, the Ministry of Truth controls all information, including news, entertainment, education, and the arts. The main protagonist in the book, Winston Smith, works in the Records Department, "rectifying" historical records to accord with Big Brother's current pronouncements so that everything the Party says appears to be true. Cadieux’s 1972 report has subtle overtones of George Orwell’s futuristic novel. Cadieux’s 1972 narrative hints at the municipality’s engagement with social manipulation and subtle, yet totalitarian control and cloaks it in reasonableness. Like the London society in the novel, Katlehong’s society appears to be controlled by mysterious elite (the Non-European Affairs Department of the City Council of Germiston and ultimately, the apartheid government). It almost seems that Julien J Cadieux is in the same situation as George Orwell’s main protagonist, Winston Smith, in that his job is tedious and tasks to promote the government’s version of history. In the case of Katlehong, it could be said that a desperate young Cadieux is conducting surveys and writing reports that deliberately simulate the municipality’s thoughtful interest in the leisure time of the local black worker class. Like Winstom Graham, Cadieux is involved in altering the truth.

Cadieux continued plodding towards the notion of recreation as a key process for the state to influence people to “self-initiate steps progressively towards a good life to offset a resigned acceptance”. He also says there can be “no more desirable and productive a pathway to self-realisation than the wholesome use of leisure time” (Cadieux 1972:4). Cadieux may have been forced to overlook the many ways that democracy, freedom and wealth would be preferable to recreation as an ‘antidote to boredom, monotony and an unimaginative existence’ for Katlehong residents. He may have even have been aware that the townships of Johannesburg would soon explode into protest and violent police responses.

The fate of recreation in Katlehong

Was the Germiston City Council of the time genuinely of the opinion that the furious and growing political violence and energy could be deflected by peaceful sport, choirs and gardening clubs? The plan for uplifting and fulfilling recreation was a of course useless when black people wanted political freedom and not soccer, and as political violence in Katlehong escalated, it would not have been safe for any person to wander around the townships in the evening seeking sport and recreation and probably useless to mention building new community halls for women’s needle work groups. During the mid-1980s, the South African government was brutally suppressing political unrest and declaring states of emergency. By the early 1990s, Katlehong was aflame with violence, fear and political killings. By 1994, South Africa was a brand new democracy led by the ANC and any type of optimistic philosophy-based township recreational planning from the past was swept away without a trace.

Sue Taylor holds a PhD in Plant Biotechnology from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and aspires to be an artist, history writer and urban explorer. She is a Research Fellow at the Afromontane Research Unit, QwaQwa, University of Free State (South Africa).

References

- Bonner P (2000). The politics of location and relocation: Germiston 1942 – 1960. African Studies, 59(2): 191-203.

- Hutta JS (2019). From sovereignty to technologies of dependence: Rethinking the power relations supporting violence in Brazil. Political Geography, 69:65-76).

- Kynoch G. (2013). Reassessing transition violence: Voices from South Africa’s Township wars, 1990–4. African Affairs, 112/447, 283–303. doi: 10.1093/afraf/adt014

Comments will load below. If for any reason none appear click here for some troubleshooting tips. If you would like to post a comment and need instructions click here.